Modelica: Equation-Based, Object-Oriented Modelling of Physical Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Applying Reinforcement Learning to Modelica Models

ModelicaGym: Applying Reinforcement Learning to Modelica Models Oleh Lukianykhin∗ Tetiana Bogodorova [email protected] [email protected] The Machine Learning Lab, Ukrainian Catholic University Lviv, Ukraine Figure 1: A high-level overview of a considered pipeline and place of the presented toolbox in it. ABSTRACT CCS CONCEPTS This paper presents ModelicaGym toolbox that was developed • Theory of computation → Reinforcement learning; • Soft- to employ Reinforcement Learning (RL) for solving optimization ware and its engineering → Integration frameworks; System and control tasks in Modelica models. The developed tool allows modeling languages; • Computing methodologies → Model de- connecting models using Functional Mock-up Interface (FMI) to velopment and analysis. OpenAI Gym toolkit in order to exploit Modelica equation-based modeling and co-simulation together with RL algorithms as a func- KEYWORDS tionality of the tools correspondingly. Thus, ModelicaGym facilit- Cart Pole, FMI, JModelica.org, Modelica, model integration, Open ates fast and convenient development of RL algorithms and their AI Gym, OpenModelica, Python, reinforcement learning comparison when solving optimal control problem for Modelica dynamic models. Inheritance structure of ModelicaGym toolbox’s ACM Reference Format: Oleh Lukianykhin and Tetiana Bogodorova. 2019. ModelicaGym: Applying classes and the implemented methods are discussed in details. The Reinforcement Learning to Modelica Models. In EOOLT 2019: 9th Interna- toolbox functionality validation is performed on Cart-Pole balan- tional Workshop on Equation-Based Object-Oriented Modeling Languages and arXiv:1909.08604v1 [cs.SE] 18 Sep 2019 cing problem. This includes physical system model description and Tools, November 04–05, 2019, Berlin, DE. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 10 pages. its integration using the toolbox, experiments on selection and in- https://doi.org/10.1145/nnnnnnn.nnnnnnn fluence of the model parameters (i.e. -

Practical Perl Tools: Scratch the Webapp Itch With

last tIme, we had the pleasure oF exploring the basics of a Web applica- DaviD n. BLank-EdeLman tion framework called CGI::Application (CGI::App). I appreciate this particular pack- age because it hits a certain sweet spot in practical Perl tools: terms of its complexity/learning curve and scratch the webapp itch with power. In this column we’ll finish up our exploration by looking at a few of the more CGI::Application, part 2 powerful extensions to the framework that David N. Blank-Edelman is the director of can really give it some oomph. technology at the Northeastern University College of Computer and Information Sci- ence and the author of the O’Reilly book Quick review Automating System Administration with Perl (the second edition of the Otter book), Let’s do a really quick review of how CGI::App available at purveyors of fine dead trees works, so that we can build on what we’ve learned everywhere. He has spent the past 24+ years as a system/network administrator in large so far. CGI::App is predicated on the notion of “run multi-platform environments, including modes.” When you are first starting out, it is easi- Brandeis University, Cambridge Technology est to map “run mode” to “Web page” in your head. Group, and the MIT Media Laboratory. He was the program chair of the LISA ’05 confer- You write a piece of code (i.e., a subroutine) that ence and one of the LISA ’06 Invited Talks will be responsible for producing the HTML for co-chairs. -

Object Oriented Programming in Java Object Oriented

Object Oriented Programming in Java Introduction Object Oriented Programming in Java Introduction to Computer Science II I Java is Object-Oriented I Not pure object oriented Christopher M. Bourke I Differs from other languages in how it achieves and implements OOP [email protected] functionality I OOP style programming requires practice Objects in Java Objects in Java Java is a class-based OOP language Definition Contrast with proto-type based OOP languages A class is a construct that is used as a blueprint to create instances of I Example: JavaScript itself. I No classes, only instances (of objects) I Constructed from nothing (ex-nihilo) I Objects are concepts; classes are Java’s realization of that concept I Inheritance through cloning of original prototype object I Classes are a definition of all objects of a specific type (instances) I Interface is build-able, mutable at runtime I Classes provide an explicit blueprint of its members and their visibility I Instances of a class must be explicitly created Objects in Java Objects in JavaI Paradigm: Singly-Rooted Hierarchy Object methods 1 //ignore: 2 protected Object clone(); 3 protected void finalize(); I All classes are subclasses of Object 4 Class<? extends Object> getClass(); 5 I Object is a java object, not an OOP object 6 //multithreaded applications: I Makes garbage collection easier 7 public void notify(); 8 public void notifyAll(); I All instances have a type and that type can be determined 9 public void wait(); I Provides a common, universal minimum interface for objects 10 public -

Reusing Static Analysis Across Di Erent Domain-Specific Languages

Reusing Static Analysis across Dierent Domain-Specific Languages using Reference Attribute Grammars Johannes Meya, Thomas Kühnb, René Schönea, and Uwe Aßmanna a Technische Universität Dresden, Germany b Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Germany Abstract Context: Domain-specific languages (DSLs) enable domain experts to specify tasks and problems themselves, while enabling static analysis to elucidate issues in the modelled domain early. Although language work- benches have simplified the design of DSLs and extensions to general purpose languages, static analyses must still be implemented manually. Inquiry: Moreover, static analyses, e.g., complexity metrics, dependency analysis, and declaration-use analy- sis, are usually domain-dependent and cannot be easily reused. Therefore, transferring existing static analyses to another DSL incurs a huge implementation overhead. However, this overhead is not always intrinsically necessary: in many cases, while the concepts of the DSL on which a static analysis is performed are domain- specific, the underlying algorithm employed in the analysis is actually domain-independent and thus can be reused in principle, depending on how it is specified. While current approaches either implement static anal- yses internally or with an external Visitor, the implementation is tied to the language’s grammar and cannot be reused easily. Thus far, a commonly used approach that achieves reusable static analysis relies on the trans- formation into an intermediate representation upon which the analysis is performed. This, however, entails a considerable additional implementation effort. Approach: To remedy this, it has been proposed to map the necessary domain-specific concepts to the algo- rithm’s domain-independent data structures, yet without a practical implementation and the demonstration of reuse. -

Better PHP Development I

Better PHP Development i Better PHP Development Copyright © 2017 SitePoint Pty. Ltd. Cover Design: Natalia Balska Notice of Rights All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Notice of Liability The author and publisher have made every effort to ensure the accuracy of the information herein. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the authors and SitePoint Pty. Ltd., nor its dealers or distributors will be held liable for any damages to be caused either directly or indirectly by the instructions contained in this book, or by the software or hardware products described herein. Trademark Notice Rather than indicating every occurrence of a trademarked name as such, this book uses the names only in an editorial fashion and to the benefit of the trademark owner with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Published by SitePoint Pty. Ltd. 48 Cambridge Street Collingwood VIC Australia 3066 Web: www.sitepoint.com Email: [email protected] ii Better PHP Development About SitePoint SitePoint specializes in publishing fun, practical, and easy-to-understand content for web professionals. Visit http://www.sitepoint.com/ to access our blogs, books, newsletters, articles, and community forums. You’ll find a stack of information on JavaScript, PHP, design, -

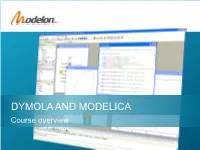

Introduction to Dymola

DYMOLA AND MODELICA Course overview DAY 1 Dymola and Modelica I • Introduction Dymola, Modelica, Modelon • Lecture 1 Overview of Dymola and Physical modeling . Workshop 1 Workflow of modeling physical systems in Dymola • Lecture 2 Simulation and post-processing with Dymola . Workshop 2 Simulating and analyzing a physical system • Lecture 3 Configure system models . Workshop 3 Creating a reconfigurable system DAY 2 Dymola and Modelica I • Lecture 4 Modelica I – Writing Modelica models . Workshop 4a Cauer low pass filter using Electric Library . Workshop 4b A moving coil using Magnetic, Electric and Translational mechanics libraries . Workshop 4c Temperature control using Heat transfer Library • Lecture 5 Understanding equation-based modeling . Workshop 5 Defining boundary conditions • Lecture 6 Trouble shooting and common pitfalls . Workshop 6 Common pitfalls DAY 3 Dymola and Modelica II • Lecture 7 Modelica II – Advanced features . Workshop 7 Implementing a solar collector • Lecture 8 Working with the Modelica Standard Library . Workshop 8a Lamp logic using StateGraph II . Workshop 8b Suspension linkage using MultiBody mechanics • Lecture 9 Hybrid modeling . Workshop 9a Hybrid examples . Workshop 9b Hammer impact model . Workshop 9c Designing a thermostat valve DAY 4 Dymola and Modelica II • Lecture 10 Efficient and reconfigurable modeling . Workshop 10 Creating a system architecture based on templates and interfaces • Lecture 11 Model variants and data management . Workshop 11 Creating a data architecture and adaptive parameter interfaces • Lecture 12 FMI technology . Workshop 12a Import and Export FMUs in Dymola . Workshop 12b FMI with Excel . Workshop 12c FMI with Simulink DAY 5 Dymola and Modelica II • Lecture 13 Workflow automation and scripting . Workshop 13 Automated sensitivity analysis • Lecture 14 Dymola code with other tools . -

Introducing Javascript OSA

Introducing JavaScript OSA Late Night SOFTWARE Contents CHAPTER 1 What is JavaScript OSA?....................................................................... 1 The OSA ........................................................................................................................ 2 Why JavaScript? ............................................................................................................ 3 CHAPTER 2 JavaScript Examples.............................................................................. 5 Learning JavaScript ....................................................................................................... 6 Sieve of Eratosthenes..................................................................................................... 7 Word Histogram Example ............................................................................................. 8 Area of a Polygon .......................................................................................................... 9 CHAPTER 3 The Core Object ................................................................................... 13 Talking to the User ...................................................................................................... 14 Places ........................................................................................................................... 14 Where Am I?................................................................................................................ 14 Who Am I? ................................................................................................................. -

Concepts in Programming Languages Practicalities

Concepts in Programming Languages Practicalities I Course web page: Alan Mycroft1 www.cl.cam.ac.uk/teaching/1617/ConceptsPL/ with lecture slides, exercise sheet and reading material. These slides play two roles – both “lecture notes" and “presentation material”; not every slide will be lectured in Computer Laboratory detail. University of Cambridge I There are various code examples (particularly for 2016–2017 (Easter Term) JavaScript and Java applets) on the ‘materials’ tab of the course web page. I One exam question. www.cl.cam.ac.uk/teaching/1617/ConceptsPL/ I The syllabus and course has changed somewhat from that of 2015/16. I would be grateful for comments on any remaining ‘rough edges’, and for views on material which is either over- or under-represented. 1Acknowledgement: various slides are based on Marcelo Fiore’s 2013/14 course. Alan Mycroft Concepts in Programming Languages 1 / 237 Alan Mycroft Concepts in Programming Languages 2 / 237 Main books Context: so many programming languages I J. C. Mitchell. Concepts in programming languages. Cambridge University Press, 2003. Peter J. Landin: “The Next 700 Programming Languages”, I T.W. Pratt and M. V.Zelkowitz. Programming Languages: CACM (published in 1966!). Design and implementation (3RD EDITION). Some programming-language ‘family trees’ (too big for slide): Prentice Hall, 1999. http://www.oreilly.com/go/languageposter http://www.levenez.com/lang/ ? M. L. Scott. Programming language pragmatics http://rigaux.org/language-study/diagram.html (4TH EDITION). http://www.rackspace.com/blog/ Elsevier, 2016. infographic-evolution-of-computer-languages/ I R. Harper. Practical Foundations for Programming Plan of this course: pick out interesting programming-language Languages. -

Lecture #4: Simulation of Hybrid Systems

Embedded Control Systems Lecture 4 – Spring 2018 Knut Åkesson Modelling of Physcial Systems Model knowledge is stored in books and human minds which computers cannot access “The change of motion is proportional to the motive force impressed “ – Newton Newtons second law of motion: F=m*a Slide from: Open Source Modelica Consortium, Copyright © Equation Based Modelling • Equations were used in the third millennium B.C. • Equality sign was introduced by Robert Recorde in 1557 Newton still wrote text (Principia, vol. 1, 1686) “The change of motion is proportional to the motive force impressed ” Programming languages usually do not allow equations! Slide from: Open Source Modelica Consortium, Copyright © Languages for Equation-based Modelling of Physcial Systems Two widely used tools/languages based on the same ideas Modelica + Open standard + Supported by many different vendors, including open source implementations + Many existing libraries + A plant model in Modelica can be imported into Simulink - Matlab is often used for the control design History: The Modelica design effort was initiated in September 1996 by Hilding Elmqvist from Lund, Sweden. Simscape + Easy integration in the Mathworks tool chain (Simulink/Stateflow/Simscape) - Closed implementation What is Modelica A language for modeling of complex cyber-physical systems • Robotics • Automotive • Aircrafts • Satellites • Power plants • Systems biology Slide from: Open Source Modelica Consortium, Copyright © What is Modelica A language for modeling of complex cyber-physical systems -

The C Programming Language

The C programming Language The C programming Language By Brian W. Kernighan and Dennis M. Ritchie. Published by Prentice-Hall in 1988 ISBN 0-13-110362-8 (paperback) ISBN 0-13-110370-9 Contents ● Preface ● Preface to the first edition ● Introduction 1. Chapter 1: A Tutorial Introduction 1. Getting Started 2. Variables and Arithmetic Expressions 3. The for statement 4. Symbolic Constants 5. Character Input and Output 1. File Copying 2. Character Counting 3. Line Counting 4. Word Counting 6. Arrays 7. Functions 8. Arguments - Call by Value 9. Character Arrays 10. External Variables and Scope 2. Chapter 2: Types, Operators and Expressions 1. Variable Names 2. Data Types and Sizes 3. Constants 4. Declarations http://freebooks.by.ru/view/CProgrammingLanguage/kandr.html (1 of 5) [5/15/2002 10:12:59 PM] The C programming Language 5. Arithmetic Operators 6. Relational and Logical Operators 7. Type Conversions 8. Increment and Decrement Operators 9. Bitwise Operators 10. Assignment Operators and Expressions 11. Conditional Expressions 12. Precedence and Order of Evaluation 3. Chapter 3: Control Flow 1. Statements and Blocks 2. If-Else 3. Else-If 4. Switch 5. Loops - While and For 6. Loops - Do-While 7. Break and Continue 8. Goto and labels 4. Chapter 4: Functions and Program Structure 1. Basics of Functions 2. Functions Returning Non-integers 3. External Variables 4. Scope Rules 5. Header Files 6. Static Variables 7. Register Variables 8. Block Structure 9. Initialization 10. Recursion 11. The C Preprocessor 1. File Inclusion 2. Macro Substitution 3. Conditional Inclusion 5. Chapter 5: Pointers and Arrays 1. -

210 CHAPTER 7. NAMES and BINDING Chapter 8

210 CHAPTER 7. NAMES AND BINDING Chapter 8 Expressions and Evaluation Overview This chapter introduces the concept of the programming environment and the role of expressions in a program. Programs are executed in an environment which is provided by the operating system or the translator. An editor, linker, file system, and compiler form the environment in which the programmer can enter and run programs. Interac- tive language systems, such as APL, FORTH, Prolog, and Smalltalk among others, are embedded in subsystems which replace the operating system in forming the program- development environment. The top-level control structure for these subsystems is the Read-Evaluate-Write cycle. The order of computation within a program is controlled in one of three basic ways: nesting, sequencing, or signaling other processes through the shared environment or streams which are managed by the operating system. Within a program, an expression is a nest of function calls or operators that returns a value. Binary operators written between their arguments are used in infix syntax. Unary and binary operators written before a single argument or a pair of arguments are used in prefix syntax. In postfix syntax, operators (unary or binary) follow their arguments. Parse trees can be developed from expressions that include infix, prefix and postfix operators. Rules for precedence, associativity, and parenthesization determine which operands belong to which operators. The rules that define order of evaluation for elements of a function call are as follows: • Inside-out: Evaluate every argument before beginning to evaluate the function. 211 212 CHAPTER 8. EXPRESSIONS AND EVALUATION • Outside-in: Start evaluating the function body. -

A Modelica Power System Library for Phasor Time-Domain Simulation

2013 4th IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Europe (ISGT Europe), October 6-9, Copenhagen 1 A Modelica Power System Library for Phasor Time-Domain Simulation T. Bogodorova, Student Member, IEEE, M. Sabate, G. Leon,´ L. Vanfretti, Member, IEEE, M. Halat, J. B. Heyberger, and P. Panciatici, Member, IEEE Abstract— Power system phasor time-domain simulation is the FMI Toolbox; while for Mathematica, SystemModeler often carried out through domain specific tools such as Eurostag, links Modelica models directly with the computation kernel. PSS/E, and others. While these tools are efficient, their individual The aims of this article is to demonstrate the value of sub-component models and solvers cannot be accessed by the users for modification. One of the main goals of the FP7 iTesla Modelica as a convenient language for modeling of complex project [1] is to perform model validation, for which, a modelling physical systems containing electric power subcomponents, and simulation environment that provides model transparency to show results of software-to-software validations in order and extensibility is necessary. 1 To this end, a power system to demonstrate the capability of Modelica for supporting library has been built using the Modelica language. This article phasor time-domain power system models, and to illustrate describes the Power Systems library, and the software-to-software validation carried out for the implemented component as well as how power system Modelica models can be shared across the validation of small-scale power system models constructed different simulation platforms. In addition, several aspects of using different library components. Simulations from the Mo- using Modelica for simulation of complex power systems are delica models are compared with their Eurostag equivalents.