Concepts in Programming Languages Practicalities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5 Names, Bindings, and Scopes

Chapter 5 Names, Bindings, and Scopes 5.1 Introduction 198 5.2 Names 199 5.3 Variables 200 5.4 The Concept of Binding 203 5.5 Scope 211 5.6 Scope and Lifetime 222 5.7 Referencing Environments 223 5.8 Named Constants 224 Summary • Review Questions • Problem Set • Programming Exercises 227 CMPS401 Class Notes (Chap05) Page 1 / 20 Dr. Kuo-pao Yang Chapter 5 Names, Bindings, and Scopes 5.1 Introduction 198 Imperative languages are abstractions of von Neumann architecture – Memory: stores both instructions and data – Processor: provides operations for modifying the contents of memory Variables are characterized by a collection of properties or attributes – The most important of which is type, a fundamental concept in programming languages – To design a type, must consider scope, lifetime, type checking, initialization, and type compatibility 5.2 Names 199 5.2.1 Design issues The following are the primary design issues for names: – Maximum length? – Are names case sensitive? – Are special words reserved words or keywords? 5.2.2 Name Forms A name is a string of characters used to identify some entity in a program. Length – If too short, they cannot be connotative – Language examples: . FORTRAN I: maximum 6 . COBOL: maximum 30 . C99: no limit but only the first 63 are significant; also, external names are limited to a maximum of 31 . C# and Java: no limit, and all characters are significant . C++: no limit, but implementers often impose a length limitation because they do not want the symbol table in which identifiers are stored during compilation to be too large and also to simplify the maintenance of that table. -

Practical Perl Tools: Scratch the Webapp Itch With

last tIme, we had the pleasure oF exploring the basics of a Web applica- DaviD n. BLank-EdeLman tion framework called CGI::Application (CGI::App). I appreciate this particular pack- age because it hits a certain sweet spot in practical Perl tools: terms of its complexity/learning curve and scratch the webapp itch with power. In this column we’ll finish up our exploration by looking at a few of the more CGI::Application, part 2 powerful extensions to the framework that David N. Blank-Edelman is the director of can really give it some oomph. technology at the Northeastern University College of Computer and Information Sci- ence and the author of the O’Reilly book Quick review Automating System Administration with Perl (the second edition of the Otter book), Let’s do a really quick review of how CGI::App available at purveyors of fine dead trees works, so that we can build on what we’ve learned everywhere. He has spent the past 24+ years as a system/network administrator in large so far. CGI::App is predicated on the notion of “run multi-platform environments, including modes.” When you are first starting out, it is easi- Brandeis University, Cambridge Technology est to map “run mode” to “Web page” in your head. Group, and the MIT Media Laboratory. He was the program chair of the LISA ’05 confer- You write a piece of code (i.e., a subroutine) that ence and one of the LISA ’06 Invited Talks will be responsible for producing the HTML for co-chairs. -

Homework 2: Reflection and Multiple Dispatch in Smalltalk

Com S 541 — Programming Languages 1 October 2, 2002 Homework 2: Reflection and Multiple Dispatch in Smalltalk Due: Problems 1 and 2, September 24, 2002; problems 3 and 4, October 8, 2002. This homework can either be done individually or in teams. Its purpose is to familiarize you with Smalltalk’s reflection facilities and to help learn about other issues in OO language design. Don’t hesitate to contact the staff if you are not clear about what to do. In this homework, you will adapt the “multiple dispatch as dispatch on tuples” approach, origi- nated by Leavens and Millstein [1], to Smalltalk. To do this you will have to read their paper and then do the following. 1. (30 points) In a new category, Tuple-Smalltalk, add a class Tuple, which has indexed instance variables. Design this type to provide the necessary methods for working with dispatch on tuples, for example, we’d like to have access to the tuple of classes of the objects in a given tuple. Some of these methods will depend on what’s below. Also design methods so that tuples can be used as a data structure (e.g., to pass multiple arguments and return multiple results). 2. (50 points) In the category, Tuple-Smalltalk, design other classes to hold the behavior that will be declared for tuples. For example, you might want something analogous to a method dictionary and other things found in the class Behavior or ClassDescription. It’s worth studying those classes to see what can be adapted to our purposes. -

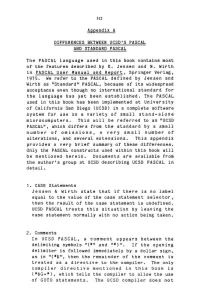

A Concurrent PASCAL Compiler for Minicomputers

512 Appendix A DIFFERENCES BETWEEN UCSD'S PASCAL AND STANDARD PASCAL The PASCAL language used in this book contains most of the features described by K. Jensen and N. Wirth in PASCAL User Manual and Report, Springer Verlag, 1975. We refer to the PASCAL defined by Jensen and Wirth as "Standard" PASCAL, because of its widespread acceptance even though no international standard for the language has yet been established. The PASCAL used in this book has been implemented at University of California San Diego (UCSD) in a complete software system for use on a variety of small stand-alone microcomputers. This will be referred to as "UCSD PASCAL", which differs from the standard by a small number of omissions, a very small number of alterations, and several extensions. This appendix provides a very brief summary Of these differences. Only the PASCAL constructs used within this book will be mentioned herein. Documents are available from the author's group at UCSD describing UCSD PASCAL in detail. 1. CASE Statements Jensen & Wirth state that if there is no label equal to the value of the case statement selector, then the result of the case statement is undefined. UCSD PASCAL treats this situation by leaving the case statement normally with no action being taken. 2. Comments In UCSD PASCAL, a comment appears between the delimiting symbols "(*" and "*)". If the opening delimiter is followed immediately by a dollar sign, as in "(*$", then the remainder of the comment is treated as a directive to the compiler. The only compiler directive mentioned in this book is (*$G+*), which tells the compiler to allow the use of GOTO statements. -

Object Oriented Programming in Java Object Oriented

Object Oriented Programming in Java Introduction Object Oriented Programming in Java Introduction to Computer Science II I Java is Object-Oriented I Not pure object oriented Christopher M. Bourke I Differs from other languages in how it achieves and implements OOP [email protected] functionality I OOP style programming requires practice Objects in Java Objects in Java Java is a class-based OOP language Definition Contrast with proto-type based OOP languages A class is a construct that is used as a blueprint to create instances of I Example: JavaScript itself. I No classes, only instances (of objects) I Constructed from nothing (ex-nihilo) I Objects are concepts; classes are Java’s realization of that concept I Inheritance through cloning of original prototype object I Classes are a definition of all objects of a specific type (instances) I Interface is build-able, mutable at runtime I Classes provide an explicit blueprint of its members and their visibility I Instances of a class must be explicitly created Objects in Java Objects in JavaI Paradigm: Singly-Rooted Hierarchy Object methods 1 //ignore: 2 protected Object clone(); 3 protected void finalize(); I All classes are subclasses of Object 4 Class<? extends Object> getClass(); 5 I Object is a java object, not an OOP object 6 //multithreaded applications: I Makes garbage collection easier 7 public void notify(); 8 public void notifyAll(); I All instances have a type and that type can be determined 9 public void wait(); I Provides a common, universal minimum interface for objects 10 public -

TAMING the MERGE OPERATOR a Type-Directed Operational Semantics Approach

Technical Report, Department of Computer Science, the University of Hong Kong, Jan 2021. 1 TAMING THE MERGE OPERATOR A Type-directed Operational Semantics Approach XUEJING HUANG JINXU ZHAO BRUNO C. D. S. OLIVEIRA The University of Hong Kong (e-mail: fxjhuang, jxzhao, [email protected]) Abstract Calculi with disjoint intersection types support a symmetric merge operator with subtyping. The merge operator generalizes record concatenation to any type, enabling expressive forms of object composition, and simple solutions to hard modularity problems. Unfortunately, recent calculi with disjoint intersection types and the merge operator lack a (direct) operational semantics with expected properties such as determinism and subject reduction, and only account for terminating programs. This paper proposes a type-directed operational semantics (TDOS) for calculi with intersection types and a merge operator. We study two variants of calculi in the literature. The first calculus, called li, is a variant of a calculus presented by Oliveira et al. (2016) and closely related to another calculus by Dunfield (2014). Although Dunfield proposes a direct small-step semantics for her calcu- lus, her semantics lacks both determinism and subject reduction. Using our TDOS we obtain a direct + semantics for li that has both properties. The second calculus, called li , employs the well-known + subtyping relation of Barendregt, Coppo and Dezani-Ciancaglini (BCD). Therefore, li extends the more basic subtyping relation of li, and also adds support for record types and nested composition (which enables recursive composition of merged components). To fully obtain determinism, both li + and li employ a disjointness restriction proposed in the original li calculus. -

Julia: a Fresh Approach to Numerical Computing

RSDG @ UCL Julia: A Fresh Approach to Numerical Computing Mosè Giordano @giordano [email protected] Knowledge Quarter Codes Tech Social October 16, 2019 Julia’s Facts v1.0.0 released in 2018 at UCL • Development started in 2009 at MIT, first • public release in 2012 Julia co-creators won the 2019 James H. • Wilkinson Prize for Numerical Software Julia adoption is growing rapidly in • numerical optimisation, differential equations, machine learning, differentiable programming It is used and taught in several universities • (https://julialang.org/teaching/) Mosè Giordano (RSDG @ UCL) Julia: A Fresh Approach to Numerical Computing October 16, 2019 2 / 29 Julia on Nature Nature 572, 141-142 (2019). doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-02310-3 Mosè Giordano (RSDG @ UCL) Julia: A Fresh Approach to Numerical Computing October 16, 2019 3 / 29 Solving the Two-Language Problem: Julia Multiple dispatch • Dynamic type system • Good performance, approaching that of statically-compiled languages • JIT-compiled scripts • User-defined types are as fast and compact as built-ins • Lisp-like macros and other metaprogramming facilities • No need to vectorise: for loops are fast • Garbage collection: no manual memory management • Interactive shell (REPL) for exploratory work • Call C and Fortran functions directly: no wrappers or special APIs • Call Python functions: use the PyCall package • Designed for parallelism and distributed computation • Mosè Giordano (RSDG @ UCL) Julia: A Fresh Approach to Numerical Computing October 16, 2019 4 / 29 Multiple Dispatch using DifferentialEquations -

Better PHP Development I

Better PHP Development i Better PHP Development Copyright © 2017 SitePoint Pty. Ltd. Cover Design: Natalia Balska Notice of Rights All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Notice of Liability The author and publisher have made every effort to ensure the accuracy of the information herein. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the authors and SitePoint Pty. Ltd., nor its dealers or distributors will be held liable for any damages to be caused either directly or indirectly by the instructions contained in this book, or by the software or hardware products described herein. Trademark Notice Rather than indicating every occurrence of a trademarked name as such, this book uses the names only in an editorial fashion and to the benefit of the trademark owner with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Published by SitePoint Pty. Ltd. 48 Cambridge Street Collingwood VIC Australia 3066 Web: www.sitepoint.com Email: [email protected] ii Better PHP Development About SitePoint SitePoint specializes in publishing fun, practical, and easy-to-understand content for web professionals. Visit http://www.sitepoint.com/ to access our blogs, books, newsletters, articles, and community forums. You’ll find a stack of information on JavaScript, PHP, design, -

Concise Introduction to C++

i i final3 2012/4/19 page 47 i i Chapter 2 Concise Introduction to C++ C++ seems to be most suitable for many practical applications. Indeed, C++ is sufficiently high-level to allow transparent object-oriented programming and efficient use of human resources, yet is also sufficiently low-level to have types, variables, pointers, arrays, and loops to allow efficient use of computer resources. In this chapter, we give a concise description of C++ and illustrate its power as an object-oriented programming language. In particular, we show how to construct and use abstract mathematical objects such as vectors and matrices. We also explain the notion of a template class, which can be filled with a concrete type later on in compilation time. We also discuss inheritance and illustrate its potential. 2.1 Objects As we have seen above, C is a language based on functions. Every command is also a function that returns a value that can be further used or abandoned, according to the wish of the programmer. Furthermore, programmers can write their own functions, which may also return variables of the type specified just before the function name. When the function is called, a temporary, unnamed variable is created to store the returned value until it has been used. C++, on the other hand, is an object-oriented programming language. In this kind of language, the major concern is not the functions that can be executed but rather the objects upon which they operate. Although C++ supports all the operations and features available in C, its point of view is different. -

Introducing Javascript OSA

Introducing JavaScript OSA Late Night SOFTWARE Contents CHAPTER 1 What is JavaScript OSA?....................................................................... 1 The OSA ........................................................................................................................ 2 Why JavaScript? ............................................................................................................ 3 CHAPTER 2 JavaScript Examples.............................................................................. 5 Learning JavaScript ....................................................................................................... 6 Sieve of Eratosthenes..................................................................................................... 7 Word Histogram Example ............................................................................................. 8 Area of a Polygon .......................................................................................................... 9 CHAPTER 3 The Core Object ................................................................................... 13 Talking to the User ...................................................................................................... 14 Places ........................................................................................................................... 14 Where Am I?................................................................................................................ 14 Who Am I? ................................................................................................................. -

Java Terms/Concepts You Should Know from OOPDA Glossary Terms

Java Terms/Concepts You Should Know from OOPDA A abstract class A class with the abstract reserved word in its header. Abstract classes are distinguished by the fact that you may not directly construct objects from them using the new operator. An abstract class may have zero or more abstract methods. abstract method A method with the abstract reserved word in its header. An abstract method has no method body. Methods defined in an interface are always abstract. The body of an abstract method must be defined in a sub class of an abstract class, or the body of a class implementing an interface. Abstract Windowing Toolkit The Abstract Windowing Toolkit (AWT) provides a collection of classes that simplify the creation of applications with graphical user interfaces. These are to be found in the java.awt packages. Included are classes for windows, frames, buttons, menus, text areas, and so on. Related to the AWT classes are those for the Swing packages. aggregation A relationship in which an object contains one or more other subordinate objects as part of its state. The subordinate objects typically have no independent existence separate from their containing object. When the containing object has no further useful existence, neither do the subordinate objects. For instance, a gas station object might contain several pump objects. These pumps will only exist as long as the station does. Aggregation is also referred to as the has-a relationship, to distinguish it from the is-a relationship, which refers to inheritance. anonymous class A class created without a class name. -

Characteristics of Mathematical Modeling Languages That

www.nature.com/npjsba ARTICLE OPEN Characteristics of mathematical modeling languages that facilitate model reuse in systems biology: a software engineering perspective ✉ Christopher Schölzel 1 , Valeria Blesius1, Gernot Ernst2,3 and Andreas Dominik 1 Reuse of mathematical models becomes increasingly important in systems biology as research moves toward large, multi-scale models composed of heterogeneous subcomponents. Currently, many models are not easily reusable due to inflexible or confusing code, inappropriate languages, or insufficient documentation. Best practice suggestions rarely cover such low-level design aspects. This gap could be filled by software engineering, which addresses those same issues for software reuse. We show that languages can facilitate reusability by being modular, human-readable, hybrid (i.e., supporting multiple formalisms), open, declarative, and by supporting the graphical representation of models. Modelers should not only use such a language, but be aware of the features that make it desirable and know how to apply them effectively. For this reason, we compare existing suitable languages in detail and demonstrate their benefits for a modular model of the human cardiac conduction system written in Modelica. npj Systems Biology and Applications (2021) 7:27 ; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41540-021-00182-w 1234567890():,; INTRODUCTION descriptions of experiment setup or design choices6–8. A recent As the understanding of biological systems grows, it becomes study by curators of the BioModels database showed that only 8 more and more apparent that their behavior cannot be reliably 51% of 455 published models were directly reproducible .Inan 9 predicted without the help of mathematical models. In the past, extreme case, Topalidou et al.