Departamento De Biología Vegetal, Escuela Técnica Superior De

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Synopsis of Phaseoleae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) James Andrew Lackey Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1977 A synopsis of Phaseoleae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) James Andrew Lackey Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Lackey, James Andrew, "A synopsis of Phaseoleae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) " (1977). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 5832. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/5832 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Diversidad Y Distribución De La Familia Asteraceae En México

Taxonomía y florística Diversidad y distribución de la familia Asteraceae en México JOSÉ LUIS VILLASEÑOR Botanical Sciences 96 (2): 332-358, 2018 Resumen Antecedentes: La familia Asteraceae (o Compositae) en México ha llamado la atención de prominentes DOI: 10.17129/botsci.1872 botánicos en las últimas décadas, por lo que cuenta con una larga tradición de investigación de su riqueza Received: florística. Se cuenta, por lo tanto, con un gran acervo bibliográfico que permite hacer una síntesis y actua- October 2nd, 2017 lización de su conocimiento florístico a nivel nacional. Accepted: Pregunta: ¿Cuál es la riqueza actualmente conocida de Asteraceae en México? ¿Cómo se distribuye a lo February 18th, 2018 largo del territorio nacional? ¿Qué géneros o regiones requieren de estudios más detallados para mejorar Associated Editor: el conocimiento de la familia en el país? Guillermo Ibarra-Manríquez Área de estudio: México. Métodos: Se llevó a cabo una exhaustiva revisión de literatura florística y taxonómica, así como la revi- sión de unos 200,000 ejemplares de herbario, depositados en más de 20 herbarios, tanto nacionales como del extranjero. Resultados: México registra 26 tribus, 417 géneros y 3,113 especies de Asteraceae, de las cuales 3,050 son especies nativas y 1,988 (63.9 %) son endémicas del territorio nacional. Los géneros más relevantes, tanto por el número de especies como por su componente endémico, son Ageratina (164 y 135, respecti- vamente), Verbesina (164, 138) y Stevia (116, 95). Los estados con mayor número de especies son Oaxa- ca (1,040), Jalisco (956), Durango (909), Guerrero (855) y Michoacán (837). Los biomas con la mayor riqueza de géneros y especies son el bosque templado (1,906) y el matorral xerófilo (1,254). -

Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae

SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO BOTANY 0 NCTMBER 52 Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae Harold Robinson, A. Michael Powell, Robert M. King, andJames F. Weedin SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS City of Washington 1981 ABSTRACT Robinson, Harold, A. Michael Powell, Robert M. King, and James F. Weedin. Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae. Smithsonian Contri- butions to Botany, number 52, 28 pages, 3 tables, 1981.-Chromosome reports are provided for 145 populations, including first reports for 33 species and three genera, Garcilassa, Riencourtia, and Helianthopsis. Chromosome numbers are arranged according to Robinson’s recently broadened concept of the Heliantheae, with citations for 212 of the ca. 265 genera and 32 of the 35 subtribes. Diverse elements, including the Ambrosieae, typical Heliantheae, most Helenieae, the Tegeteae, and genera such as Arnica from the Senecioneae, are seen to share a specialized cytological history involving polyploid ancestry. The authors disagree with one another regarding the point at which such polyploidy occurred and on whether subtribes lacking higher numbers, such as the Galinsoginae, share the polyploid ancestry. Numerous examples of aneuploid decrease, secondary polyploidy, and some secondary aneuploid decreases are cited. The Marshalliinae are considered remote from other subtribes and close to the Inuleae. Evidence from related tribes favors an ultimate base of X = 10 for the Heliantheae and at least the subfamily As teroideae. OFFICIALPUBLICATION DATE is handstamped in a limited number of initial copies and is recorded in the Institution’s annual report, Smithsonian Year. SERIESCOVER DESIGN: Leaf clearing from the katsura tree Cercidiphyllumjaponicum Siebold and Zuccarini. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Chromosome numbers in Compositae, XII. -

Plant List for Web Page

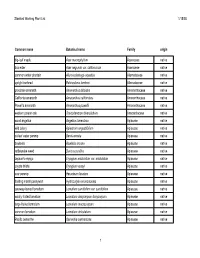

Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 Common name Botanical name Family origin big-leaf maple Acer macrophyllum Aceraceae native box elder Acer negundo var. californicum Aceraceae native common water plantain Alisma plantago-aquatica Alismataceae native upright burhead Echinodorus berteroi Alismataceae native prostrate amaranth Amaranthus blitoides Amaranthaceae native California amaranth Amaranthus californicus Amaranthaceae native Powell's amaranth Amaranthus powellii Amaranthaceae native western poison oak Toxicodendron diversilobum Anacardiaceae native wood angelica Angelica tomentosa Apiaceae native wild celery Apiastrum angustifolium Apiaceae native cutleaf water parsnip Berula erecta Apiaceae native bowlesia Bowlesia incana Apiaceae native rattlesnake weed Daucus pusillus Apiaceae native Jepson's eryngo Eryngium aristulatum var. aristulatum Apiaceae native coyote thistle Eryngium vaseyi Apiaceae native cow parsnip Heracleum lanatum Apiaceae native floating marsh pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides Apiaceae native caraway-leaved lomatium Lomatium caruifolium var. caruifolium Apiaceae native woolly-fruited lomatium Lomatium dasycarpum dasycarpum Apiaceae native large-fruited lomatium Lomatium macrocarpum Apiaceae native common lomatium Lomatium utriculatum Apiaceae native Pacific oenanthe Oenanthe sarmentosa Apiaceae native 1 Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 wood sweet cicely Osmorhiza berteroi Apiaceae native mountain sweet cicely Osmorhiza chilensis Apiaceae native Gairdner's yampah (List 4) Perideridia gairdneri gairdneri Apiaceae -

USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Region Sensitive Plant Species by Forest

USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Region 1 Sensitive Plant Species by Forest 2013 FS R5 RF Plant Species List Klamath NF Mendocino NF Shasta-Trinity NF NF Rivers Six Lassen NF Modoc NF Plumas NF EldoradoNF Inyo NF LTBMU Tahoe NF Sequoia NF Sierra NF Stanislaus NF Angeles NF Cleveland NF Los Padres NF San Bernardino NF Scientific Name (Common Name) Abies bracteata (Santa Lucia fir) X Abronia alpina (alpine sand verbena) X Abronia nana ssp. covillei (Coville's dwarf abronia) X X Abronia villosa var. aurita (chaparral sand verbena) X X Acanthoscyphus parishii var. abramsii (Abrams' flowery puncturebract) X X Acanthoscyphus parishii var. cienegensis (Cienega Seca flowery puncturebract) X Agrostis hooveri (Hoover's bentgrass) X Allium hickmanii (Hickman's onion) X Allium howellii var. clokeyi (Mt. Pinos onion) X Allium jepsonii (Jepson's onion) X X Allium marvinii (Yucaipa onion) X Allium tribracteatum (three-bracted onion) X X Allium yosemitense (Yosemite onion) X X Anisocarpus scabridus (scabrid alpine tarplant) X X X Antennaria marginata (white-margined everlasting) X Antirrhinum subcordatum (dimorphic snapdragon) X Arabis rigidissima var. demota (Carson Range rock cress) X X Arctostaphylos cruzensis (Arroyo de la Cruz manzanita) X Arctostaphylos edmundsii (Little Sur manzanita) X Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. gabrielensis (San Gabriel manzanita) X X Arctostaphylos hooveri (Hoover's manzanita) X Arctostaphylos luciana (Santa Lucia manzanita) X Arctostaphylos nissenana (Nissenan manzanita) X X Arctostaphylos obispoensis (Bishop manzanita) X Arctostphylos parryana subsp. tumescens (interior manzanita) X X Arctostaphylos pilosula (Santa Margarita manzanita) X Arctostaphylos rainbowensis (rainbow manzanita) X Arctostaphylos refugioensis (Refugio manzanita) X Arenaria lanuginosa ssp. saxosa (rock sandwort) X Astragalus anxius (Ash Valley milk-vetch) X Astragalus bernardinus (San Bernardino milk-vetch) X Astragalus bicristatus (crested milk-vetch) X X Pacific Southwest Region, Regional Forester's Sensitive Species List. -

Fruits and Seeds of Genera in the Subfamily Faboideae (Fabaceae)

Fruits and Seeds of United States Department of Genera in the Subfamily Agriculture Agricultural Faboideae (Fabaceae) Research Service Technical Bulletin Number 1890 Volume I December 2003 United States Department of Agriculture Fruits and Seeds of Agricultural Research Genera in the Subfamily Service Technical Bulletin Faboideae (Fabaceae) Number 1890 Volume I Joseph H. Kirkbride, Jr., Charles R. Gunn, and Anna L. Weitzman Fruits of A, Centrolobium paraense E.L.R. Tulasne. B, Laburnum anagyroides F.K. Medikus. C, Adesmia boronoides J.D. Hooker. D, Hippocrepis comosa, C. Linnaeus. E, Campylotropis macrocarpa (A.A. von Bunge) A. Rehder. F, Mucuna urens (C. Linnaeus) F.K. Medikus. G, Phaseolus polystachios (C. Linnaeus) N.L. Britton, E.E. Stern, & F. Poggenburg. H, Medicago orbicularis (C. Linnaeus) B. Bartalini. I, Riedeliella graciliflora H.A.T. Harms. J, Medicago arabica (C. Linnaeus) W. Hudson. Kirkbride is a research botanist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Systematic Botany and Mycology Laboratory, BARC West Room 304, Building 011A, Beltsville, MD, 20705-2350 (email = [email protected]). Gunn is a botanist (retired) from Brevard, NC (email = [email protected]). Weitzman is a botanist with the Smithsonian Institution, Department of Botany, Washington, DC. Abstract Kirkbride, Joseph H., Jr., Charles R. Gunn, and Anna L radicle junction, Crotalarieae, cuticle, Cytiseae, Weitzman. 2003. Fruits and seeds of genera in the subfamily Dalbergieae, Daleeae, dehiscence, DELTA, Desmodieae, Faboideae (Fabaceae). U. S. Department of Agriculture, Dipteryxeae, distribution, embryo, embryonic axis, en- Technical Bulletin No. 1890, 1,212 pp. docarp, endosperm, epicarp, epicotyl, Euchresteae, Fabeae, fracture line, follicle, funiculus, Galegeae, Genisteae, Technical identification of fruits and seeds of the economi- gynophore, halo, Hedysareae, hilar groove, hilar groove cally important legume plant family (Fabaceae or lips, hilum, Hypocalypteae, hypocotyl, indehiscent, Leguminosae) is often required of U.S. -

A New Species of the Brazilian Endemic Genus <I>Acritopappus</I

Systematic Botany (2011), 36(1): pp. 227–230 © Copyright 2011 by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists DOI 10.1600/036364411X553298 A New Species of the Brazilian Endemic Genus Acritopappus (Compositae, Eupatorieae) from Minas Gerais Hortensia P. Bautista , 1 Santiago Ortiz , 2 , 3 and Juan Rodríguez-Oubiña 2 1 Departamento de Ciências da Vida, Universidade do Estado da Bahia, Rua Silveira Martins, 2555, Cabula. CEP 41150-0000, Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. 2 Departamento de Bioloxía Vexetal, Laboratorio de Botánica, Facultade de Farmacia, Universidade de Santiago, 15782 Santiago de Compostela, Galicia, Spain. 3 Author for correspondence: ( [email protected] ) Communicating Editor: Mark P. Simmons Abstract— A new species of the Brazilian endemic genus Acritopappus from the Serra do Cabral, in Minas Gerais state, is described. The new species, Acritopappus pereirae , is similar to A. confertus , the most widely distributed species in the genus, but differs in that the latter has conduplicate, chartaceous, glabrous to glabrescent, viscid leaves with entire margins, and an aristate pappus. The new species is illus- trated, the affinities between the morphologically related species and A. pereirae are discussed and a key to the species from Minas Gerais is provided. Keywords— Asteraceae , Brazil , Serra do Cabral , subtribe Ageratinae , systematics , taxonomy. Acritopappus R. M. King & H. Rob. (Compositae, Materials and Methods Eupatorieae) consists of 17 species of shrubs and small trees, This study was based on morphological analysis of specimens from mostly endemic to the northeast and southeast regions of the following herbaria: BHCB, CEPEC, HRB, HUEFS, K, SANT, and US Brazil ( Bautista 2000 ). The greatest diversity of the genus (herbarium acronyms follow Holmgren et al. -

Nuclear and Plastid DNA Phylogeny of the Tribe Cardueae (Compositae

1 Nuclear and plastid DNA phylogeny of the tribe Cardueae 2 (Compositae) with Hyb-Seq data: A new subtribal classification and a 3 temporal framework for the origin of the tribe and the subtribes 4 5 Sonia Herrando-Morairaa,*, Juan Antonio Callejab, Mercè Galbany-Casalsb, Núria Garcia-Jacasa, Jian- 6 Quan Liuc, Javier López-Alvaradob, Jordi López-Pujola, Jennifer R. Mandeld, Noemí Montes-Morenoa, 7 Cristina Roquetb,e, Llorenç Sáezb, Alexander Sennikovf, Alfonso Susannaa, Roser Vilatersanaa 8 9 a Botanic Institute of Barcelona (IBB, CSIC-ICUB), Pg. del Migdia, s.n., 08038 Barcelona, Spain 10 b Systematics and Evolution of Vascular Plants (UAB) – Associated Unit to CSIC, Departament de 11 Biologia Animal, Biologia Vegetal i Ecologia, Facultat de Biociències, Universitat Autònoma de 12 Barcelona, ES-08193 Bellaterra, Spain 13 c Key Laboratory for Bio-Resources and Eco-Environment, College of Life Sciences, Sichuan University, 14 Chengdu, China 15 d Department of Biological Sciences, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN 38152, USA 16 e Univ. Grenoble Alpes, Univ. Savoie Mont Blanc, CNRS, LECA (Laboratoire d’Ecologie Alpine), FR- 17 38000 Grenoble, France 18 f Botanical Museum, Finnish Museum of Natural History, PO Box 7, FI-00014 University of Helsinki, 19 Finland; and Herbarium, Komarov Botanical Institute of Russian Academy of Sciences, Prof. Popov str. 20 2, 197376 St. Petersburg, Russia 21 22 *Corresponding author at: Botanic Institute of Barcelona (IBB, CSIC-ICUB), Pg. del Migdia, s. n., ES- 23 08038 Barcelona, Spain. E-mail address: [email protected] (S. Herrando-Moraira). 24 25 Abstract 26 Classification of the tribe Cardueae in natural subtribes has always been a challenge due to the lack of 27 support of some critical branches in previous phylogenies based on traditional Sanger markers. -

Alkali Milk-Vetch)

Glenn Counties (California Natural Diversity Data Base 2001 and unprocessed data). Five occurrences are afforded some protection by virtue of their location on public land, but no particular conservation efforts have been undertaken in those areas. 2. ASTRAGALUS TENER VAR. TENER (ALKALI MILK-VETCH) a. Description and Taxonomy Taxonomy.—Alkali milk-vetch is in the pea family Fabaceae. Gray (1864) named Astragalus tener, commonly known as alkali milk-vetch. He gave the type locality only as “California ... from near Monterey or San Francisco” (Gray 1864:206). No varieties were named until Barneby (1950) reduced Astragalus titi, commonly known as coastal dunes milk-vetch, from a full species to the variety Astragalus tener var. titi. In so doing, the combination Astragalus tener var. tener was created automatically to represent Gray’s original material (i.e., alkali milk-vetch), according to accepted rules of botanical nomenclature. Another common name by which this variety is known is slender rattle-weed (Abrams 1944). Description and Identification.—Astragalus tener var. tener (Figure II-22) is similar in most respects to A. tener var. ferrisiae. However, the two taxa differ in leaflet shape and fruit morphology. Astragalus tener var. tener leaflets vary, even on the same plant, from narrow and pointed to wedge-shaped with blunt or notched tips. In A. tener var. tener, the pod is only 1 to 2.5 centimeters (0.4 to 1.0 inch) long and straight or only slightly curved. The base of the pod is typically rounded; if stalk-like, the base is much less than 3 millimeters (0.12 inch) long. -

Universidad Nacional Del Centro Del Peru

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DEL CENTRO DEL PERU FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS FORESTALES Y DEL AMBIENTE "COMPOSICIÓN FLORÍSTICA Y ESTADO DE CONSERVACIÓN DE LOS BOSQUES DE Kageneckia lanceolata Ruiz & Pav. Y Escallonia myrtilloides L.f. EN LA RESERVA PAISAJÍSTICA NOR YAUYOS COCHAS" TESIS PARA OPTAR EL TÍTULO PROFESIONAL DE INGENIERO FORESTAL Y AMBIENTAL Bach. CARLOS MICHEL ROMERO CARBAJAL Bach. DELY LUZ RAMOS POCOMUCHA HUANCAYO – JUNÍN – PERÚ JULIO – 2009 A mis padres Florencio Ramos y Leonarda Pocomucha, por su constante apoyo y guía en mi carrera profesional. DELY A mi familia Héctor Romero, Eva Carbajal y Milton R.C., por su ejemplo de voluntad, afecto y amistad. CARLOS ÍNDICE AGRADECIMIENTOS .................................................................................. i RESUMEN .................................................................................................. ii I. INTRODUCCIÓN ........................................................................... 1 II. REVISIÓN BIBLIOGRÁFICA ........................................................... 3 2.1. Bosques Andinos ........................................................................ 3 2.2. Formación Vegetal ...................................................................... 7 2.3. Composición Florística ................................................................ 8 2.4. Indicadores de Diversidad ......................................................... 10 2.5. Biología de la Conservación...................................................... 12 2.6. Estado de Conservación -

Kentropyx Paulensis (Boettger, 1893) and Tupinambis Duseni Lönnberg, 1910

Check List 10(6): 1549–1554, 2014 © 2014 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (available at www.biotaxa.org/cl) Journal of species lists and distribution N New records of the teiid lizards Kentropyx paulensis (Boettger, 1893) and Tupinambis duseni Lönnberg, 1910 ISTRIBUTIO (Squamata: Teiidae) from the state of Minas Gerais, D southeastern Brazil RAPHIC G EO Leandro de Oliveira Drummond 1*, António Jorge do Rosário Cruz 2, Henrique Caldeira Costa 3 and G N Caryne Aparecida de Carvalho Braga 1 O OTES 1 Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Departamento de Ecologia, Laboratório de Vertebrados. CP 68020, Ilha do Fundão. CEP 21941-901, Rio N de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. 2 Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, Laboratório de Zoologia dos Vertebrados, Instituto de Ciências Exatas e Biológicas, Campus Morro do Cruzeiro, 35400-000 Ouro Preto, MG, Brazil 3 Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Programa de Pós Graduação em Zoologia, Pampulha, 31270-901, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. * Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Kentropyx paulensis and Tupinambis duseni are teiid lizard species endemic to the Cerrado ecoregion. They are, respectively, considered “Vulnerable” and “Near Threatened” in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Herein, we report the occurrence of both species in the municipality of Buenópolis, Minas Gerais, representing their easternmost locality and the second state record. An updated distribution map for K. paulensis and T. duseni is presented. DOI: 10.15560/10.6.1549 The Teiidae family is composed of about 140 New arboreal formations like riparian forests and cerradões World lizard species (Uetz and Hošek 2014), ranging from (Nogueira et al.