BMW Sauber F1 Team

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution-Guide 2003

Evolution-Guide by Norbert Illbruck Inhalt 25401 Porsche 911 GT1 Evo "Le Mans '97" 25402 Porsche 911 GT1 Evo "JB Racing" 25403 Porsche 911 GT1 Evo "Rohr Motorsport" 25404 Porsche 911 GT1 Evo "Champion Racing Daytona 1998" 25405 Porsche 911 GT1 Evo "Larbre Competition Dijon 1998" 25406 Porsche 911 GT1 Evo "Team FES" 25407 Dodge Viper GTS-R "Team Oreca '97" 25408 Dodge Viper GTS-R "Chamberlain Engineering" 25409 Dodge Viper GTS-R "Team Carrera" 25412 Porsche GT1 '98 "Zakspeed" 25413 Porsche GT1 '98 "Le Mans" 25414 Porsche GT1 '98 "Le Mans 1998" - chromatiert 25418 Audi R8 R “Le Mans ‘99” 25420 BMW V12 LMR "Le Mans 99" 25421 Mercedes Benz 300 SLR "Mille Miglia 1955" 25422 Maserati A6 GCS "Mille Miglia 1954" 25423 Sauber-Petronas C18 25424 McLaren-Mercedes MP4/15 "Mika" 25425 BMW V12 LMR "BMW Motorsport ALMS 2000" 25426 McLaren-Mercedes MP4/15 "Magny Cours 2000" 25427 Maserati A6 GCS "Lolo´s Maserati Emilia Romagna” 25428 Ford Mustang GT 350 "1966" 25429 Chevrolet Corvette Sting Ray 427 '67 25430 Panoz LMP07 Roadster "Race of a thousand years" 25431 Panoz LMP07 Roadster "Sebring 50th anniversary" 25432 Aston Martin DB3 "Mille Miglia 1953" 25433 Aston Martin DB3 "Historic Racer"- silberner Kühlergrill 25433 Aston Martin DB3 "Historic Racer" - gelber Kühlergrill 25434 Maserati A6 GCS "Mille Miglia 1996" 25435 Audi R8R "ALMS 2000" 25436 BMW V12 LMR "Art Car" 25437 BMW Williams F1 FW23 "R.Schumacher" - lackierter Fahrerhelm 25437 BMW Williams F1 FW23 "R.Schumacher" - gelber Fahrerhelm 25438 BMW Williams F1 FW23 "J.P. Montoya" - lackierter Fahrerhelm 25438 BMW Williams F1 FW23 "J.P. -

Thebusinessofmotorsport ECONOMIC NEWS and ANALYSIS from the RACING WORLD

Contents: 2 November 2009 Doubts over Toyota future Renault for sale? Mercedes and McLaren: divorce German style USF1 confirms Aragon and Stubbs Issue 09.44 Senna signs for Campos New idea in Abu Dhabi Bridgestone to quit F1 at the end of 2010 Tom Wheatcroft A Silverstone deal close Graham Nearn Williams to confirm Barrichello and Hulkenberg this week Vettel in the twilight zone thebusinessofmotorsport ECONOMIC NEWS AND ANALYSIS FROM THE RACING WORLD Doubts over Toyota future Toyota is expected to announce later this week that it will be withdrawing from Formula 1 immediately. The company is believed to have taken the decision after indications in Japan that the automotive markets are not getting any better, Honda having recently announced a 56% drop in earnings in the last quarter, compared to 2008. Prior to that the company was looking at other options, such as selling the team on to someone else. This has now been axed and the company will simply close things down and settle all the necessary contractual commitments as quickly as possible. The news, if confirmed, will be another blow to the manufacturer power in F1 as it will be the third withdrawal by a major car company in 11 months, following in the footsteps of Honda and BMW. There are also doubts about the future of Renault's factory team. The news will also be a blow to the Formula One Teams' Association, although the members have learned that working together produces much better results than trying to take on the authorities alone. It also means that there are now just three manufacturers left: Ferrari, Mercedes and Renault, and engine supply from Cosworth will become essential to ensure there are sufficient engines to go around. -

10 Years of BMW F1 Engines Abstract

- 1 - Prof. Dr.-Ing. Mario Theissen, Dipl.-Ing. Markus Duesmann, Dipl.-Ing. Jan Hartmann, Dipl.-Ing. Matthias Klietz, Dipl.-Ing. Ulrich Schulz BMW Group, Munich 10 Years of BMW F1 Engines Abstract BMW engines gave the company a presence in Formula One from 2000 to 2009. The overall project can be broken down into a preparatory phase, its years as an engine supplier to the Williams team, and a period competing under the banner of its own BMW Sauber F1 Team. The conception, design and deployment of the engines were defined by the Formula One regulations, which were subject to change virtually every year. Reducing costs was the principal aim of these revisions. Development expenditure was scaled down gradually as a result of the technical restrictions imposed on the teams and finally through homologation and a freeze on development. Engine build costs were limited by the increased mileage required of each engine and the restrictions on testing. A lower number of engines were therefore required for each season. A second aim, reduced engine output, was achieved with the switch from 3.0-litre V10 engines to 2.4-litre V8s for the 2006 season. In the early years of its involvement in F1, BMW developed and built a new engine for each season amid a high-pressure competitive environment. This process saw rapid improvements made in engine output and weight, and the BMW powerplant soon attained benchmark status in F1. In recent years, development work focused on raising mileage capability and reliability without changing the engine concept itself. The P86/9 of the 2009 season achieved the same engine output, despite a 20% reduction in displacement, of the E41/4 introduced at the beginning of the 2000 season. -

Efficient Dynamics

A subsidiary of BMW AG BMW U.S. Press Information For Release: August 8, 2016 Contact: Alex Schmuck Manager, BMW Product and Technology Communications Cell 201-675-6697 / [email protected] Thomas Plucinsky Department Head, BMW Group Product Communications Cell 201-406-4801 / [email protected] BMW Celebrates Centenary Throughout Monterey Car Week 2016. Woodcliff Lake, N.J. – August 8, 2016…In the largest celebration this year outside of Munich, BMW will celebrate the 100th anniversary of its founding and its illustrious racing history at the four premiere events of Monterey Car Week from August 18-21 in Monterey, California. As a featured marquee at the Rolex Monterey Motorsports Reunion, The Quail - A Motorsports Gathering, Legends of the Autobahn and at the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance, visitors can be assured that each event will have a compelling representation of the cars and people that have defined The Ultimate Driving Machine® for ten decades. BMW is the featured marquee at the Rolex Monterey Motorsports Reunion and the brand will be represented by 64 vintage BMW race cars ranging from a strong group of 1930’s 328s to the all concurring BMW V12 LMR of 1999. The Rolex Reunion promises to be the largest gathering of BMW M1 ProCars ever assembled in the USA. Finally, all five factory IMSA specification 3.0 CSLs will be back together for the first time since they raced in1975 and 1976. Among the 64 BMWs racing in the Rolex Reunion will be seven cars from the BMWUSA Classic collection. Drivers will include BMW of North America Chairman Ludwig Willisch and several past and current BMW Motorsport drivers. -

3 February 2006 Maserati Celebrates Its Champions

Date: 3 February 2006 Maserati celebrates its Champions Trident Drivers and Teams from last Season. First look at 2006 Programme. The prize giving ceremony to award drivers and teams who competed in a Maserati car in 2005 takes place this evening in Modena. At international level, Maserati won the FIA GT Constructors' title thanks to the efforts of Vitaphone Racing Team and JMB Racing. Further, the Vitaphone Racing Team triumphed in the Team championship and in the prestigious 24 Hours of Spa, claiming Maserati's first ever win in a 24-Hour race. The Michael Bartels/Timo Scheider/Eric Van de Poele squad crossed the line ahead of the other MC12 driven by Bertolini/Wendlinger/Peter. It was a clear demonstration of the reliability of the cars bearing the Trident badge. In total, there were three wins aside from that claimed at Spa: Magny Cours courtesy of Andrea Bertolini/Karl Wendlinger; at Oschersleben with Fabio Babini/Thomas Biagi; and at Istanbul where Michael Bartels/Timo Scheider took the chequered flag. In the Italian GT championship, team Racing Box finished in second place overall thanks to five wins obtained by Piergiuseppe Perazzini/Gabriele Matteuzzi. Another significant result was secured at the 6 Hours of Vallelunga, a 'classic' endurance race that is run at the end of the season. Here, the winning crew was made up of Davide Mastracci/Michele Serafini/Leonardo Maddalena. In the Trofeo Nazionale CSAI GT3, the Maserati Lights stormed a path through the competition with three cars that secured all the places on the championship podium. Andrea Palma and Danilo Zampaloni were the overall winners in their AF Corse car. -

Forgotten F1 Teams – Series 1 Omnibus Simtek Grand Prix

Forgotten F1 Teams – Series 1 Omnibus Welcome to Forgotten F1 Teams – a mini series from Sidepodcast. These shows were originally released over seven consecutive days But are now gathered together in this omniBus edition. Simtek Grand Prix You’re listening to Sidepodcast, and this is the latest mini‐series: Forgotten F1 Teams. I think it’s proBaBly self explanatory But this is a series dedicated to profiling some of the forgotten teams. Forget aBout your Ferrari’s and your McLaren’s, what aBout those who didn’t make such an impact on the sport, But still have a story to tell? Those are the ones you’ll hear today. Thanks should go to Scott Woodwiss for suggesting the topic, and the teams, and we’ll dive right in with Simtek Grand Prix. Simtek Grand Prix was Born from Simtek Research Ltd, the name standing for Simulation Technology. The company founders were Nick Wirth and Max Mosley, Both of whom had serious pedigree within motorsport. Mosley had Been a team owner Before with March, and Wirth was a mechanical engineering student who was snapped up By March as an aerodynamicist, working underneath Adrian Newey. When March was sold to Leyton House, Mosley and Wirth? Both decided to leave, and joined forces to create Simtek. Originally, the company had a single office in Wirth’s house, But it was soon oBvious they needed a Bigger, more wind‐tunnel shaped Base, which they Built in Oxfordshire. Mosley had the connections that meant racing teams from all over the gloBe were interested in using their research technologies, But while keeping the clients satisfied, Simtek Began designing an F1 car for BMW in secret. -

The Chequered Flag

THE CHEQUERED March 2016 Issue 1 FLAG F101 MR322G £100 MR191 £295 1985 British Lewis Hamilton Truck Grand signed Formula 1 Prix Silverstone photo, our choice programme. Signed inside by two-time Moto GP World Champion Barry Sheene who later turned to Truck Racing, plus tickets MR225 £295 Pedro Rodriguez De La Vega signed ticket MR273 £100 Patrick Head, Adrian Newey, and Ross Brawn signed 2010 Sixty Years of Formula One Silverstone cover, they were all engineers MR322F £150 1987 Truck Prix signed official MR238 £350 Brands Hatch Graham Hill signed 4 x 6 photo programme. mounted onto card Signed inside by Rod Chapman (7x European Truck Champ) Barry Sheene (2x Moto GP Champ) Davina Galica (F1), Barry Lee (4x Truck World Champ), plus tickets MR117A £175 01303 278137 Michael EMAIL: [email protected] Schumacher signed photo, our choice Buckingham Covers, Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF 1 Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] SIGNED SILVERSTONE 2010 - 60 YEARS OF F1 Occassionally going round fairs you would find an odd Silverstone Motor Racing cover with a great signature on, but never more than one or two and always hard to find. They were only ever on sale at the circuit, and were sold to raise funds for things going on in Silverstone Village. Being sold on the circuit gave them access to some very hard to find signatures, as you can see from this initial selection. MR261 £30 MR262 £25 MR77C £45 Father and son drivers Sir Jackie Jody Scheckter, South African Damon Hill, British Racing Driver, and Paul Stewart. -

Davide Signed with Alpine F1 Team in January 2021 As

ALPINE F1 TEAM PRESS PACK Already recognised for its records It is part of Groupe Renault’s Luca De Meo, CEO Groupe That’s the beauty of racing as In September 2020, Luca De Meo, and successes in endurance strategy to clearly position Renault: “It is a true joy to see a works team in Formula 1. announced the creation of Alpine F1 Team, and rallying, the Alpine name each of its brands. For Alpine, the powerful, vibrant Alpine We will compete against the naturally finds its place in the this is a key step to accelerate name on a Formula One car. biggest names, for spectacular a renaissance of Groupe Renault’s F1 team, high standards, prestige and the development and influence New colours, new managing car races made and followed one of F1’s most historic and successful. performance of Formula 1. The of the brand. Renault remains team, ambitious plans: it’s a new by cheering enthusiasts. I can’t Alpine brand, a symbol of sporting an integral part of the team, beginning, building on a 40-year wait for the season to start.” prowess, elegance and agility, with the hybrid power unit history. We’ll combine Alpine’s will be designated to the chassis retaining its Renault E-Tech values of authenticity, elegance and pay tribute to the expertise moniker and unique expertise and audacity with our in-house that gave birth to the A110. in hybrid powertrains. engineering & chassis expertise. ALPINE F1 TEAM | PRESS PACK | 2021 Alpine Today and Tomorrow As part of Groupe Renault’s strategic plan ‘Renaulution’, Alpine unveiled its long-term plans to position the brand at the forefront of Groupe Renault’s innovation. -

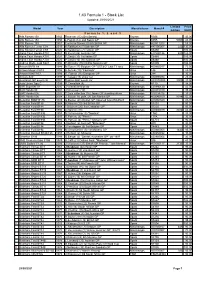

Stock List Updated 28/09/2021

1:43 Formula 1 - Stock List Updated 28/09/2021 Limited Price Model Year Description Manufacturer Manuf # Edition (AUD) F o r m u l a 1 , 2 a n d 3 Alfa Romeo 158 1950 Race car (25) (Oro Series) Brumm R036 35.00 Alfa Romeo 158 1950 L.Fagioli (12) 2nd Swiss GP Brumm S055 5000 40.00 Alfa Romeo 159 1951 Consalvo Sanesi (3) 6th British GP Minichamps 400511203 55.00 Alfa Romeo Ferrari C38 2019 K.Raikkonen (7) Bahrain GP Minichamps 447190007 222 135.00 Alfa Romeo Ferrari C39 2020 K.Raikkonen (7) Turkish GP Spark S6492 100.00 Alpha Tauri Honda AT01 2020 D.Kvyat (26) Austrian GP Minichamps 417200126 400 125.00 Alpha Tauri Honda AT01 2020 P.Gasly (10) 1st Italian GP Spark S6480 105.00 Alpha Tauri Honda AT01 2020 P.Gasly (10) 7th Austrian GP Spark S6468 100.00 Andrea Moda Judd S921 1992 P.McCathy (35) DNPQ Monaco GP Spark S3899 100.00 Arrows BMW A8 1986 M.Surer (17) Belgium GP "USF&G" Last F1 race Minichamps 400860017 75.00 Arrows Mugen FA13 1992 A.Suzuki (10) "Footwork" Onyx 146 25.00 Arrows Hart FA17 1996 R. Rosset (16) European GP Onyx 284 30.00 Arrows A20 1999 T.Takagi (15) show car Minichamps 430990084 25.00 Australian GP Event car 2001 Qantas AGP Event car Minichamps AC4010300 3000 40.00 Auto Union Tipo C 1936 R.Gemellate (6) Brumm R110 38.00 BAR Supertec 01 2000 J.Villeneuve test car Minichamps 430990120 40.00 BAR Honda 03 2001 J.Villeneuve (10) Minichamps 400010010 35.00 BAR Honda 005 2003 T.Sato collection (16) Japan GP standing driver Minichamps 518034316 35.00 BAR Honda 006 2004 J. -

Der Ehrgeizling

Schübel, Horst (MSa 46/2005) Der Ehrgeizling orst Schübel wollte als Teambesitzer chen einer Starparade: Christian Danner, Hstets besser, perfekter und cleverer Kris Nissen, Michael Bartels, Michele Al- sein als seine Kollegen. Das trieb ihn rund boreto, Gabriele Tarquini, Giorgio Francia um die Uhr an, als der fränkische Kfz-Meis- und Andy Wallace steuerten die allradge- ter nach Beendigung seiner aktiven Hob- triebenen V6-Boliden. Dass Nissen und by-Rennfahrerzeit 1985 den Entschluss Danner jeweils sein Heimrennen auf dem fasste, einen eigenen Rennstall zu grün- Norisring gewannen, machte den Nürnber- den. Mit dem Argentinier Victor Rosso ger besonders stolz. setzte er seine ehrgeizigen Pläne gleich im An der Noris musste er allerdings auch ersten Jahr mit dem Gewinn der Formel- den grössten Schock verarbeiten, als 1988 Ford-2000-Meisterschaft um. Dann wagte der für sein F3-Team startende Ungar Csa- er sich an die Formel 3, wo Bernd Schnei- ba Kesjar im Abschlusstraining tödlich ver- der seinem Teamchef 1987 mit einer Re- unglückte. Nach zähem STW-Engagement kordsiegesserie den DM-Titel und damit als Ford-Mondeo-Werksteam und einem eine Art Ritterschlag bescherte. teuren Porsche-GT1-Projekt beendete der Als die deutsche Sporthoheit ONS (die erfolgsverwöhnte Teamchef vor knapp heute DMSB heisst) den Franken mit der zehn Jahren seine Renn-Aktivitäten. «Ich Durchführung der F3-Nachwuchsförderung hatte die Schnauze gestrichen voll», ge- beauftragte, galt das Team bereits als ers- steht Schübel. «Erst bricht die DTM zusam- te Adresse. Zu den Jungtalenten, die durch men, dann der Zirkus mit dem STW-Mon- Schübels Hände gingen, gehörte auch deo – es hat keinen Spass mehr gemacht.» Heinz Harald Frentzen, der sich 1989 mit Ein Rennsport-Comeback mag der mitt- den Kollegen Michael Schumacher und Karl lerweile 54-Jährige trotzdem nicht aus- Wendlinger bis zum Finale duellierte und schliessen, zumal die Infrastruktur von den F3-Titelkampf nur mit einem Punkt Schübel Engineering nach wie vor exis- Rückstand verlor. -

The Mexican Grand Prix 1963-70

2015 MEXICAN GRAND PRIX • MEDIA GUIDE 03 WELCOME MESSAGE 04 MEDIA ACCREDITATION CENTRE AND MEDIA CENTRE Location Maps Opening Hours 06 MEDIA CENTRE Key Staff Facilities (IT • Photographic • Telecoms) Working in the Media Centre 09 PRESS CONFERENCE SCHEDULE 10 PHOTOGRAPHERS’ SHUTTLE BUS SCHEDULE 11 RACE TIMETABLE 15 USEFUL INFORMATION Airline numbers Rental car numbers Taxi companies 16 MAPS AND DIAGRAMS Circuit with Media Centre Media Centre layout Circuit with corner numbers Photo positions map Hotel Maps 22 2015 FIA FORMULA ONE™ WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP Entry List Calendar Standings after round 16 (USA) (Drivers) Standings after round 16 (USA) (Constructors) Team & driver statistics (after USA) 33 HOW IT ALL STARTED 35 MEXICAN DRIVERS IN THE WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP 39 MÉXICO IN WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP CONTEXT 40 2015 SUPPORT RACES 42 BACKGROUNDERS BIENVENIDO A MÉXICO! It is a pleasure to welcome you all to México as we celebrate our country’s return to the FIA Formula 1 World Championship calendar. Twice before, from 1963 to 1970 and from 1986 to 1992, México City has been the scene of exciting World Championship races. We enjoy a proud heritage in the sport: from the early brilliance of the Rodríguez brothers, the sterling efforts of Moisés Solana and Héctor Rebaque to the modern achievements of Esteban Gutíerrez and Sergio Pérez, Mexican drivers have carved their own names in the history of the sport. A few of you may have been here before. You will find many things the same – yet different. The race will still take place in the parkland of Magdalena Mixhuca where great names of the past wrote their own page in Mexican history, but the lay-out of the 21st-century track is brand-new. -

Twenty-Five Years of Motorsports at Schaeffler

IN POLE POSITION IN POLE POSITION IN INPOLE POLE Martin TomczykMartin Tomczykwins the 2011wins theDTM, 2011 a sensational DTM, a sensational achievement achievement that also thatshowcases also showcases the 2008 thePhoenix 2008 DTMPhoenix Audi. DTM Decorated Audi. Decorated in in SchaefflerSchaeffler colors, this colors, car allows this car Tomczyk allows toTomczyk earn his to firstearn hisDTM firsttitle andDTM title and underscoresunderscores the automotive the automotive supplier’s supplier’s commitment commitment to motorsports, to motorsports, which comeswhich full comes circle full after circle spanning after spanning two and a two half and decades a half ofdecades of sponsoringsponsoring with the LuK,with FAG,the LuK, and FAG,INA Group and INA logos. Group logos. POSITIONPOSITION In “In PoleIn Position”, “In Pole Position”, authors Jörg authors Walz Jörg and Walz Helge and Gerdes Helge take Gerdes a closer take a closer Focus Focusand Precision and Precision at the at Highest the Highest Level –Level – look at Schaeffler’slook at Schaeffler’s racing connection, racing connection, which began which with began rally withexpert rally expert Twenty-FiveTwenty-Five Years Yearsof Motorsports of Motorsports at Schaeffler at Schaeffler Armin SchwarzArmin andSchwarz developed and developed to include to programs include programs for the legendary for the legendary Dakar RallyDakar and Rally Formula and andFormula truck and racing. truck racing. Focus and Precision at the Highest Level – Twenty-Five of Motorsports Years at Schaeffler Focus and Precision at the Highest Level – Twenty-Five of Motorsports Years at Schaeffler Jörg Walz Helge Gerdes IN POLE POSITION Focus and Precision at the Highest Level – Twenty-Five Years of Motorsports at Schaeffler OPENING WORD Maria-Elisabeth Schaeffler MARIA-ELISABETH SCHAEFFLER PARTNER OF THE SCHAEFFLER GROUP 2 DEAR READERS, otorsports is unique in many ways, starting with a history that is virtually Mas old as the automobile itself.