We Can't Help It If We're from Florida’: a Discursive Analysis of the 1980S Gainesville Punk Subculture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freezine Pdf0040.Pdf

09/2012 Mighty v osmém vydání zdá se teď být jen zdání jako deštík, co nás zkrápěl každý den, ať kdokoli pěl. Mírný vánek na Čápáku vál kdekdo z nás se hurikánu bál bylo vše však velmi krásné, Mysli naše byly jasné. Ačkoliv jsem předala před časem vedení To však spíše trochu kecám, Mighty Freezinu Anselmovi, pořád na Mighty nikdo není sám, samozřejmě cítím vůči tomuto výjimečnému přítele či přítelkyni, časopisu náklonnost, něžnost a jsem na něj ať morgana či jackyni, tak trochu pyšná. Anselmo s Marcelem si do- každý najde, co hledá, cela dobře vedou, na to, že jsou to jen muži. (někdy až do oběda). Dnes, když můžu oslovit statisíce čtenářů Každopádně štěstí tryská v úvodníku, nevím, jak nejlépe vystihnout ze Čápova letiska. vše, čím mé srdce překypuje. Rozhodla jsem se tedy poctít vás (nás všechny) uměním Bylo to zas velmi hutné nejvyšším: poezií. Mohla bych tuto skvělou Nyní je to trochu smutné, báseň zařadit do své sbírky, která bude brzy ale jelikož to letí, vydána (a bude to bestseller, takže sledujte brzy bude, milé děti, svá oblíbená knihkupectví a včas si toto Mighty číslo nula devět - výjimečné dílo obstarejte). Ale raději ji stačí přečíst několik vět věnuji vám, milí obyčejní mighty lidé. Mám každý měsíc. Tenhle plátek vás (docela) ráda. Vaše Mq pak ohlásí ten velký svátek! DYING Ladrogang presents FETUS 23.9. Klub 007 Strahov THE KLINGONZ (uk/irl), ROCKET DOGZ (cz) Psychobilly rock´n´roll invasion from outter space! 30.9. Klub 007 Strahov Revocation 02.10.2012 Cerebral Bore WARHEAD (jap), FUK (uk, ex-Chaos UK), PORKERIA (usa) ostravaostrava - bbarakBARRÁK This is kick ass punk! Japan vs UK vs Texas! 4.10. -

Razorcake Issue #82 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California not-for-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

Hurricane Festival in Scheeßel

HURRICANE FESTIVAL 2014 TIMETABLE FREITAG TIMETABLE SAMSTAG TIMETABLE SONNTAG GREEN STAGE BLUE STAGE RED STAGE WHITE STAGE GREEN STAGE BLUE STAGE RED STAGE WHITE STAGE GREEN STAGE BLUE STAGE RED STAGE WHITE STAGE 12:00 12:00 12:00 12:00 12:00 TONBANDGERÄT THE BOTS SAMARIS 14:00 12:30 12:30 12:30 12:30 13:00 STATION 17 12:45 SONIC. THE MACHINE 13:00 BLAUDZUN ABBY 13:00 13:00 13:00 DILLINGER ESCAPE PLAN FINDUS BLOOD RED SHOES 15:00 15:00 15:00 13:30 13:30 REIGNWOLF 13:30 THE DURANGO RIOT 15:15 I HEART SHARKS 13:35 RAZZ ROYAL BLOOD 15:30 JOHNNY FLYNN & THE SUSSEX WIT 14:00 TO KILL A KING 14:00 LONDON GRAMMAR 14:05 14:00 14:00 DRENGE 14:15 16:00 16:00 16:00 SKINDRED CURRENT SWELL 14:30 DISPATCH 14:30 16:15 GEORGE EZRA CIRCA WAVES WE INVENTED PARIS DAVE HAUSE FUCKED UP FEINE SAHNE FISCHFILET 15:00 14:45 15:00 14:45 TWIN ATLANTIC METRONOMY 17:00 16:45 17:00 15:15 15:15 15:15 THE NAKED AND FAMOUS CHUCK RAGAN ZEBRAHEAD BALTHAZAR 15:30 15:30 17:15 17:15 16:00 THE PREATURES 16:00 JENNIFER ROSTOCK 15:45 YOUNG REBEL SET THE SUBWAYS APOLOGIES, I HAVE NONE 18:00 16:00 MIDLAKE 18:00 18:00 16:15 16:30 FÜNF STERNE DELUXE PASSENGER 18:30 THE SOUNDS ANGUS & JULIA STONE 17:00 16:45 16:45 17:00 16:45 16:45 18:30 DONOTS AUGUSTINES DEAF HAVANA 17:00 MARCUS WIEBUSCH 19:00 FLOGGING MOLLY WE BUTTER THE BREAD WITH BUTTER WHITE LIES POLIÇA 19:15 17:30 19:15 18:00 18:00 17:45 CHVRCHES 18:00 BASTILLE 18:00 18:00 20:00 19:45 BOMBAY BICYCLE CLUB 19:45 BONAPARTE YOU ME AT SIX BROILERS THE ASTEROIDS GALAXY TOUR THE 1975 18:15 ELBOW 19:00 19:00 18:30 FRANZ FERDINAND 18:45 -

Exploring Lesbian and Gay Musical Preferences and 'LGB Music' in Flanders

Observatorio (OBS*) Journal, vol.9 - nº2 (2015), 207-223 1646-5954/ERC123483/2015 207 Into the Groove - Exploring lesbian and gay musical preferences and 'LGB music' in Flanders Alexander Dhoest*, Robbe Herreman**, Marion Wasserbauer*** * PhD, Associate professor, 'Media, Policy & Culture', University of Antwerp, Sint-Jacobsstraat 2, 2000 Antwerp ([email protected]) ** PhD student, 'Media, Policy & Culture', University of Antwerp, Sint-Jacobsstraat 2, 2000 Antwerp ([email protected]) *** PhD student, 'Media, Policy & Culture', University of Antwerp, Sint-Jacobsstraat 2, 2000 Antwerp ([email protected]) Abstract The importance of music and music tastes in lesbian and gay cultures is widely documented, but empirical research on individual lesbian and gay musical preferences is rare and even fully absent in Flanders (Belgium). To explore this field, we used an online quantitative survey (N= 761) followed up by 60 in-depth interviews, asking questions about musical preferences. Both the survey and the interviews disclose strongly gender-specific patterns of musical preference, the women preferring rock and alternative genres while the men tend to prefer pop and more commercial genres. While the sexual orientation of the musician is not very relevant to most participants, they do identify certain kinds of music that are strongly associated with lesbian and/or gay culture, often based on the play with codes of masculinity and femininity. Our findings confirm the popularity of certain types of music among Flemish lesbians and gay men, for whom it constitutes a shared source of identification, as it does across many Western countries. The qualitative data, in particular, allow us to better understand how such music plays a role in constituting and supporting lesbian and gay cultures and communities. -

Razorcake Issue

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 #19 www.razorcake.com ight around the time we were wrapping up this issue, Todd hours on the subject and brought in visual aids: rare and and I went to West Hollywood to see the Swedish band impossible-to-find records that only I and four other people have RRRandy play. We stood around outside the club, waiting for or ancient punk zines that have moved with me through a dozen the show to start. While we were doing this, two young women apartments. Instead, I just mumbled, “It’s pretty important. I do a came up to us and asked if they could interview us for a project. punk magazine with him.” And I pointed my thumb at Todd. They looked to be about high-school age, and I guess it was for a About an hour and a half later, Randy took the stage. They class project, so we said, “Sure, we’ll do it.” launched into “Dirty Tricks,” ripped right through it, and started I don’t think they had any idea what Razorcake is, or that “Addicts of Communication” without a pause for breath. It was Todd and I are two of the founders of it. unreal. They were so tight, so perfectly in time with each other that They interviewed me first and asked me some basic their songs sounded as immaculate as the recordings. On top of questions: who’s your favorite band? How many shows do you go that, thought, they were going nuts. Jumping around, dancing like to a month? That kind of thing. -

Various Punk O Rama 10 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Punk O Rama 10 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock Album: Punk O Rama 10 Country: US Released: 2005 Style: Hardcore, Punk, Hip Hop MP3 version RAR size: 1649 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1109 mb WMA version RAR size: 1690 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 546 Other Formats: DTS AIFF AUD APE AAC ADX XM Tracklist Hide Credits CD-01 –Motion City Soundtrack When "You're" Around 2:50 CD-02 –Matchbook Romance Lovers & Liars 3:19 Shoot Me In The Smile CD-03 –The Matches 3:30 Recorded By, Producer – Matt Radosevich CD-04 –From First To Last Failure By Designer Jeans 3:03 CD-05 –Sage Francis Sun Vs. Moon 3:18 News From The Front Engineer [Mixing Assistant] – Milton ChanEngineer CD-06 –Bad Religion 2:22 [Tracking Assistant] – Dick KaneshiroMixed By – Andy WallaceProducer – Andy Wallace, Bad Religion CD-07 –This Is Me Smiling Mixin' Up Adjectives 3:03 CD-08 –Youth Group Shadowland 3:36 From The Tops Of The Trees Mixed By [Assistant], Mastered By [Assistant] – Andy CD-09 –Scatter The Ashes HuntProducer, Recorded By, Mixed By, Mastered By 3:42 – Jacquire KingRecorded By [Assistant], Mixed By [Assistant] – Sang Park I Need Drugs CD-10 –Some Girls 1:02 Producer, Written-By – Some Girls Mince Meat CD-11 –Dangerdoom* Musician – Danger MouseVocals – MF DoomWritten- 2:35 By – B. Burton*, D. Dumile* Mission From God CD-12 –The Offspring 2:55 Mixed By – Joe BarresiRecorded By – Thom Wilson CD-13 –Converge Black Cloud 2:21 CD-14 –Hot Water Music Last Goodbyes 3:00 Anchors Aweigh (Live) CD-15 –The Bouncing Souls 2:09 Mixed By – Bob Stakele*, -

The Educative Experience of Punk Learners

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 6-1-2014 "Punk Has Always Been My School": The Educative Experience of Punk Learners Rebekah A. Cordova University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons Recommended Citation Cordova, Rebekah A., ""Punk Has Always Been My School": The Educative Experience of Punk Learners" (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 142. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/142 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. “Punk Has Always Been My School”: The Educative Experience of Punk Learners __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Morgridge College of Education University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Rebekah A. Cordova June 2014 Advisor: Dr. Bruce Uhrmacher i ©Copyright by Rebekah A. Cordova 2014 All Rights Reserved ii Author: Rebekah A. Cordova Title: “Punk has always been my school”: The educative experience of punk learners Advisor: Dr. Bruce Uhrmacher Degree Date: June 2014 ABSTRACT Punk music, ideology, and community have been a piece of United States culture since the early-1970s. Although varied scholarship on Punk exists in a variety of disciplines, the educative aspect of Punk engagement, specifically the Do-It-Yourself (DIY) ethos, has yet to be fully explored by the Education discipline. -

D'eurockéennes

25 ans d’EUROCKÉENNES LE CRÉDIT AGRICOLE FRANCHE-COMTÉ NE VOUS LE DIT PAS SOUVENT : IL EST LE PARTENAIRE INCONTOURNABLE DES ÉVÉNEMENTS FRANCs-COMTOIS. IL SOUTIENT Retrouvez le Crédit Agricole Franche-Comté, une banque différente, sur : www.ca-franchecomte.fr Caisse Régionale de Crédit Agricole Mutuel de Franche-Comté - Siège social : 11, avenue Elisée Cusenier 25084 Besançon Cedex 9 -Tél. 03 81 84 81 84 - Fax 03 81 84 82 82 - www.ca-franchecomte.fr - Société coopérative à capital et personnel variables agréée en tant qu’établissement de crédit - 384 899 399 RCS Besançon - Société de courtage d’assurance immatriculée au Registre des Intermédiaires en Assurances sous le n° ORIAS 07 024 000. ÉDITO SOMMAIRE La fête • 1989 – 1992 > Naissance d’un festival > L’excellence et la tolérance, François Zimmer .......................................................p.4 > Une grosse aventure, Laurent Arnold ...................................................................p.5 continue > « Caomme un pèlerinage », Laurent Arnold ........................................................p.6 Les Eurockéennes ont 25 ans. Qui l’eut > Un air de Woodstock au pied du Ballon d’Alsace, Thierry Boillot .......................p.7 cru ? Et si aujourd’hui en 2013, un doux • 1993 – 1997 > Les Eurocks, place incontournable rêveur déposait sur la table le dossier d’un grand et beau festival de musiques > Les Eurocks, précurseurs du partenariat, Lisa Lagrange ..................................... p.8 actuelles (selon la formule consacrée), > Internet : le partenariat de -

VAGRANT RECORDS the Lndie to Watch

VAGRANT RECORDS The lndie To Watch ,Get Up Kids Rocket From The Crypt Alkaline Trio Face To Face RPM The Detroit Music Fest Report 130.0******ALL FOR ADC 90198 LOUD ROCK Frederick Gier KUOR -REDLANDS Talkin' Dirty With Matt Zane No Motiv 5319 Honda Ave. Unit G Atascadero, CA 93422 HIP-HOP Two Decades of Tommy Boy WEEZER HOLDS DOWN el, RADIOHEAD DOMINATES TOP ADDS AIR TAKES CORE "Tommy's one of the most creative and versatile multi-instrumentalists of our generation." _BEN HARPER HINTO THE "Geggy Tah has a sleek, pointy groove, hitching the melody to one's psyche with the keen handiness of a hat pin." _BILLBOARD AT RADIO NOW RADIO: TYSON HALLER RETAIL: ON FEDDOR BILLY ZARRO 212-253-3154 310-288-2711 201-801-9267 www.virginrecords.com [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 2001 VIrg. Records Amence. Inc. FEATURING "LAPDFINCE" PARENTAL ADVISORY IN SEARCH OF... EXPLICIT CONTENT %sr* Jeitetyr Co owe Eve« uuwEL. oles 6/18/2001 Issue 719 • Vol 68 • No 1 FEATURES 8 Vagrant Records: become one of the preeminent punk labels The Little Inclie That Could of the new decade. But thanks to a new dis- Boasting a roster that includes the likes of tribution deal with TVT, the label's sales are the Get Up Kids, Alkaline Trio and Rocket proving it to be the indie, punk or otherwise, From The Crypt, Vagrant Records has to watch in 2001. DEPARTMENTS 4 Essential 24 New World Our picks for the best new music of the week: An obit on Cameroonian music legend Mystic, Clem Snide, Destroyer, and Even Francis Bebay, the return of the Free Reed Johansen. -

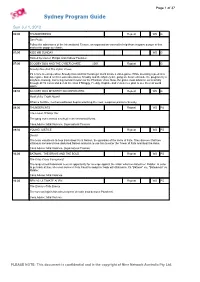

Sydney Program Guide

Page 1 of 37 Sydney Program Guide Sun Jul 1, 2012 06:00 THUNDERBIRDS Repeat WS G Sun Probe Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G Hosted by Lauren Phillips and Andrew Faulkner. 07:00 SCOOBY DOO AND THE CYBER CHASE 2001 Repeat G Scooby Doo And The Cyber Chase It's a race to escape when Scooby-Doo and his friends get stuck inside a video game. While sneaking a peek at a laser game based on their own adventures, Scooby and the Mystery Inc. gang are beamed inside the program by a mayhem-causing, menacing monster known as the Phantom Virus. Now, the game must advance successfully through all 10 levels and defeat the virus if Shaggy, Freddy, Daphne and Velma ever plan to see the real world again. 08:30 SCOOBY DOO MYSTERY INCORPORATED Repeat WS G Howl of the Fright Hound When a horrible, mechanized beast begins attacking the town, suspicion points to Scooby. 09:00 THUNDERCATS Repeat WS PG The Forest Of Magi Oar The gang come across a school in an enchanted forest. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence, Supernatural Themes 09:30 YOUNG JUSTICE Repeat WS PG Denial The team volunteers to help track down Kent Nelson, the guardian of the Helm of Fate. They discover that two villainous sorcerers have abducted Nelson and plan to use him to enter the Tower of Fate and steal the Helm. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence, Supernatural Themes 10:00 BATMAN: THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD Repeat WS PG The Criss Cross Conspiracy! The long-retired Batwoman sees an opportunity for revenge against the villain who humiliated her: Riddler. -

RAR Newsletter 120321.Indd

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 3/21/2012 Joe Pug “The Great Despiser” The first single from the album of the same name, on your desk and going for adds on Monday! In stores April 24 Early adds at WNKU, WUMB and KLCC Features backing vocals from Craig Finn of The Hold Steady Great shows at SXSW! Extensive tour runs April 20 through June 6, many dates with David Wax Museum “Pug’s scorching poetry and soulful ‘every phrase could be my last’ voice will stop you cold.” - Paste The Mastersons “One Word More” The first single from their debut album Birds Fly South on New West Records, going for adds on Monday Added early at KUT, WKZE, WFIV and WNTI Single on your desk, full cd on the way now Killer at SXSW The Mastersons are husband and wife Chris Masterson and Eleanor Whitmore, who both play in Steve Earle’s band Album in stores 4/10 Upcoming tour: 3/23 Austin, 3/25 Houston, 4/9 NYC, 4/14 Ithaca (w/Rhett Miller), 4/19 Nashvillle... Chuck Ragan “Meet You In The Middle” The first single from his new album Covering Ground on SideOneDummy, in stores, on your desk and going for adds now Featuring vocals from Brian Fallon of Gaslight Anthem, and the album features Chris Thorn of Blind Melon & more Originally from punk rock’s Hot Water Music, this is Chuck’s third album as a solo musician Fantastic shows at SXSW Fronting The Revival Tour with Dan Andriano, Cory Branan, Nathaniel Rateliff & others, sponsored by Daytrotter and Paste Dar Williams “Summer Child” Sister Sparrow & The Dirty Birds “Make It Rain” FMQB #1 Most Added!! First week: WCLZ, WFUV, WDST, WMVY, WVMP, The first single from their new album Pound Of Dirt, in stores now WCNR, KPIG, WKZE, KNBA, WFIV.. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

THIS COULD ONLY BE HAPPENING HERE: PLACE AND IDENTITY IN GAINESVILLE’S ZINE COMMUNITY By FIONA E STEWART-TAYLOR A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2019 © 2019 Fiona E. Stewart-Taylor To the Civic Media Center and all the people in it ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank, first, my committee, Dr. Margaret Galvan and Dr. Anastasia Ulanowicz. Dr. Galvan has been a critical reader, engaged teacher, and generous with her expertise, feedback, reading lists, and time. This thesis has very much developed out of discussions with her about the state of the field, the interventions possible, and her many insights into how and why to write about zines in an academic context have guided and shaped this project from the start. Dr. Ulanowicz is also a generous listener and a valuable reader, and her willingness to enter this committee at a late stage in the project was deeply kind. I would also like to thank Milo and Chris at the Queer Zine Archive Project for an incredible residency during which, reading Minneapolis zines reviewing drag revues, I began to articulate some of my ideas about the importance of zines to build community in physical space, zines as living interventions into community as well as archival memory. Chris and Milo were unfailingly welcoming, friendly, and generous with their time, expertise, and long memories, as well as their vegan sloppy joes. QZAP remains an inspiration for my own work with the Civic Media Center.