KENNETH 1. BRAY: HIS Contributlon to MUSIC EDUCATION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toronto Chamber Choir Consort 33 Yorkminstrels Show Choir 33 Executive Director from the Maestro 14 Elizabeth Shannon, Toronto Toronto Mass Choir 34

Choirs Ontario’s Newsletter January 2015 |Volume 43, Issue 2 Dynamicwww.choirsontario.org Dynamic is published four times a year by Choirs Ontario. Repro- duction or translation of any work herein without the express permis- Contents sion of Choirs Ontario is unlawful. Choirs Ontario Editor, design & layout Linda T. Cooke Editor’s Letter 3 [email protected] President’s Message 3 Canadian Military Wives 7 OYC 2015 Auditions 4 Editorial Dynamic welcomes your letters, President’s Leadership Award, 2015 5 commentary, photos, audio clips, RAM Koor Concert Tour 6 video files, and article submissions. Concert Listing 35 send to: [email protected] Festivals and Events 36 Subscriptions Job Openings / Singers Wanted 36 Subscriptions are available through membership in Choirs Ontario. Features SingOntario 9 Advertising Canadian Military Wives Choir 7 Info. on advertising contracts, rates SingOntario! Festival 9 & specifications: 416.923.1144 or Unisong Choral Festival 11 [email protected] Choirs in the Trenches 12 Choirs Ontario. Music Director Leads Three Choirs 13 1422 Bayview Ave. Toronto M4G 3A7 416.923.1144 or 1.866.935.1144 f: 416.929.0415 From The “Maestro” Unisong Choral Festival 11 [email protected] Programming Challenging Music 14 Charitable registration: 11906 7536 RR0001 Upbeat Board of Directors Amabile Youth Singers 16 President Bach Music Festival Chamber Choir 17 Rachel R.-Hoff, St. Catharines Canadian Men’s Chorus 18 Past President Cantabile Chamber Singers 19 Dean J.-Bevans, Thunder Bay Choirs In the Trenches -

Winter-2013.Pdf

Alumni Gazette WEStern’S ALUMNI MAGAZINE SINCE 1939 WINTER 2013 Power player TTC Chair Karen Stintz Alumni Gazette CONTENTS See public health from SAGT YIN on track 12 Karen Stintz, BA’92, Dipl’93, Chair of TTC a new vantage point STA Y THIRSTY 14 FOR ADVENTURE John Marcus Payne, LLB’73, has almost done it all OSCAR WINNER FIRST 16 MUSIC HALL OF FAMER Composer Barbara Willis Sweet, BMus’75 STOPPING YOUR OWN 18 GLOBAL WARMING Cardiologist & author Bradley J. Dibble, MD’90 W RITING code for 20 WEBSITES is fun? Web designer Amanda Aitken, BA’05, Cert’05 WHO IS WATCHING 26 THE POLICE? Director of Ontario’s SIU Ian Scott, LLB’81 NO JOKE: FAILURE CAN 30 LEAD TO SUCCESS Comedian and writer Deepak Sethi, BSc’02 The new Master of Public Health. 26 Get ready to lead. DEPARTMENTS @ alumnigazette.ca LETTERS CONSUMER GUIDE 05 Impressed by student spirit 28 Top 5 wines to drink now at Homecoming MAKING THE FRENCH CONNECTION BEST KEPT SECRET P URSUING JOINT PHD LIFE-ALTERING CAMPUS NEWS 32 Famous signatures in Western EXPERIENCE for KristEN SNELL, BSC’09, 07 Clinical trials of AIDS vaccine Archives MSC’11 making progress THE ROAD TO HOLLYWOOD NEW RELEASES Q & A WITH COMEDY WRITER DEEPAK SETHI, 36 Save the Humans by Rob CAMPUS QUOTES BSC’02 09 Western hosts guest speakers Stewart, BSc’01 A CAREER OF PERSISTANCE MEMORIES GAZETTEER AN EXpaNDED story ON DR. Masashi • 12 months full-time APPLY NOW • Deadline March 1 22 Winter Carnival on UC Hill 41 Alumni notes & Kawasaki, BA’53, MD’57 • intensive case-based learning schulich.uwo.ca/publichealth announcements SAVE THE HUMANS – EXCERPT • interdisciplinary faculty BY ROB STEWART, BSC’01 • 12-week practicum On the cover: Karen Stintz, BA’92, Dipl’93 (Political Science, King’s) is chair of the Toronto • international field trip Transit Commission (TTC). -

Town of Franklin Annual Report 2009

TOWN OF FRANKLIN 2009 ANNUAL R EPORT 1 2 3 TABLE OF C ONTENTS Animal Control………………………………………………………………….............................................….78 Assessors, Board of…………………………………………………………...........................………............162 Board of Appeals………………………….…………………………………………..…………................…….82 Zoning Board of Appeal Decisions for 2008…..............................................................................83 Building Inspection Department …………….………………......................……………………………..……86 Cable Television Advisory Committee ……………………………….....................…………….……………..88 Charles River Pollution Control District……………………………………………………………............……91 Conservation Commission.........................................................................................................................93 Cultural Council ........................................................................................................................................94 Design Review Committee....................................................................................................................... 94 Elected and Appointed Town Officials.........................................................................................................6 Facts on Franklin.............................................................................................................. Inside Back Cover Finance Committee....................................................................................................................................95 -

Lsm11-6 Ayout

sm20-7_EN_p01_coverV2_sm20-1_BI_pXX 15-06-03 12:55 PM Page 1 RCM_LaScenaMusicale_4c_fp_June+Aug15.qxp_Layoutsm20-7_EN_p02_rcmAD_sm20-1_BI_pXX 15-06-03 12:56 1 2015-05-27PM Page 2 9:33 AM Page 1 2015.16 Terence CONCERT Blanchard SEASON More than 85 classical, jazz, pop, world music, and family concerts to choose from! Koerner Hall / Mazzoleni Concert Hall / Conservatory Theatre Igudesman & Joo Daniel Hope Vilde Frang Jan Lisiecki SUBSCRIPTIONS ON SALE 10AM FRIDAY JUNE 12 SINGLE TICKETS ON SALE 10AM FRIDAY JUNE 19 416.408.0208 www.performance.rcmusic.ca 273 BLOOR STREET WEST (BLOOR ST. & AVENUE RD.) TORONTO sm20-7_EN_p03_torontosummerAD_sm20-1_BI_pXX 15-06-03 12:57 PM Page 3 CELEBRATING 10 YEARS JUL 16-AUG 9 DANISH STRING KARITA MATTILA QUARTET GARRICK AMERICAN OHLSSON AVANT-GARDE DANILO YOA ORCHESTRA OF THE AMERICAS PÉREZ WITH INGRID FLITER AND MUCH MORE! UNDER 35 YEARS OLD? TICKETS ONLY $20! TORONTOSUMMERMUSIC.COM 416-408-0208 an Ontario government agency un organisme du gouvernement de l’Ontario sm20-7_EN_p04_TOC_sm20-1_BI_pXX 15-06-03 12:58 PM Page 4 VOL 20-7 JUNE/JULY/AUGUST 2015 CONTENTS 10 INDUSTRY NEWS 11 Orchestre National de Jazz - Montréal 12 Jazz Festival Picks 14 Classical Festival Picks 19 Arts Festival Picks 21 Summer Listening GUIDES 22 Canadian Summer Festivals 37 REGIONAL CALENDAR 38 CONCERT PREVIEWS YOA ORCHESTRA OF THE AMERICAS 6 FOUNDING EDITORS PUBLISHER OFFICE MANAGER TRANSLATORS SUBSCRIPTIONS Wah Keung Chan, Philip Anson Wah Keung Chan Brigitte Objois Michèle Duguay, Véronique Frenette, Surface mail subscriptions (Canada) cost EDITOR-IN-CHIEF SUBSCRIPTIONS & DISTRIBUTION Cecilia Grayson, Eric Legault, $33/ yr (taxes included) to cover postage and La Scena Musicale VOL. -

Box # # of Items in Folder Name of Organization

Box # of Name of Organization (note: names that are underlined are filed by the underlined word in alphabetical order) Location # Items in Folder 1 1 Feike Asma. Organ recital. Toronto Toronto 1 ARS NOVA presents Theatre of Early Music presents "Star of Wonder" A Christmas Concert. Knox Presbyterian Church, Ottawa Ottawa. 1 ARS Omnia with Contemporary Music Projects presents The Inspiration of Greece and China. A trans-cultural Toronto contemporary music event. Kings College Circle, University of Toronto. 1 2 ARS Organi. Montreal 1 L'ARMUQ Quebec 1 1 A Benefit Concert for Women's College Hospital. John Arpin, [Pianist.]. Women's College Hospital 75th Anniversary, Toronto 1911-1986. Roy Thomson Hall, Toronto. 1 1 A Space - Toronto. Toronto 1 L'Academie Commerciale Catholique de Montreal. Montreal 1 1 L'Academie Des Lettres Et Des Sciences Humaine de la Society Royal Du Canada. [Ottawa?] 1 1 Academy of Dance. [Brantford, Ontario?] 2 Acadia University. Wolfville, Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia 1 2 ACME Theatre Company. Toronto 1 2 Acting Company. Toronto. Toronto 1 1 The Actors Workshop. Toronto. Toronto 1 1 Acustica International Montreal. Montreal 1 1 John Adams. New Music for synthesizers, solo bass and grand pianos by John Adams & Chan Ka Nin. Premiere Dance Toronto Theatre. New Music Concert. [Toronto.] 1 1 Adelaide Court Theatre. Toronto. Toronto 1 1 The Aeolian Town Hall. The London School Of Church Music. A Concert to honour the Silver Jubilee of Her Majesty London, Ontario Queen Elizabeth II. 1 Aetna Canada Young People's Concerts. Toronto. Toronto 1 2 Afternoon Concert Series. The Women's Musical Club of Toronto. -

The Beat Magazine Summer 2013

Issue 39 | Summer 2013 Amy Wright Summer Theatre Round Up Über Cool Art summer 2013 thebeatmagazine.ca | 1 The Beauties Matt Dusk ALANNAH MYLES - LIVE OCTOBER 11 & 12, 2013 DOWN ON THE CORNER: MUSIC OF CCR NOVEMBER 8 & 9, 2013 CHRISTMAS ROCKS DECEMBER 13 & 14, 2013 KINGS OF CORDUROY: SONGS OF THE ‘70S JANUARY 24 & 25, 2014 MATT DUSK: MY FUNNY VALENTINE FEBRUARY 14 &15, 2014 THE BEST OF THE BAND MARCH 28 & 29, 2014 START ME UP: MUSIC OF THE ROLLING STONES MAY 16 & 17, 2014 SUBSCRIPTIONS ON SALE NOW! 2 | thebeatmagazine.caorchestralondon.ca 519.679.8778summer 2013 summer 2013 thebeatmagazine.ca | 3 Editor’s Beat EDITORIAL Summer 2013 London seems to have made headlines for all the wrong reasons this year: record-high unemployment, Publisher/Managing Editor stagnant immigration figures, and a mayor with Dance Richard Young 30 legal issues. [email protected] Amy Wright London-based Amy Wright is one But summer is finally here, and with it comes plenty of Editor of Canada’s top choreographers. reasons to celebrate living in the Forest City. Nicole Laidler Anan Islam [email protected] In fact, there are so many cultural events going on in Cover photo by David Cooper and around town over the next three months that it Online Theatre Editor Photography was hard to squeeze them all into one issue. Donald D’Haene [email protected] For me, summer doesn’t truly start until Sunfest takes visual arts theatre over Victoria Park. Nothing epitomizes how London Copy Editor 06 spotlight Beth Stewart Vincent and Ondaatje 24 has changed from the homogeneous town of my Beth Stewart Deborah Hay childhood like seeing people from all corners of the Kathy Rumleski Art Director world come together to experience the sights, sounds Lionel Morise visual arts and tastes of each other’s culture. -

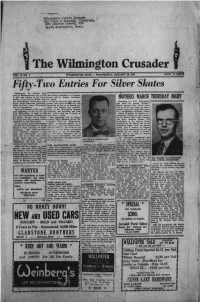

The Wilmington Crusader

Wilmington public- JAbrary . ' Mrs Clara P Cbipman, Librarian, 206 Andover Street, RED Uortb Wilmington, Maaa. The Wilmington Crusader VOL. 18 NO. 4 WILMINGTON, MASS. - WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 26,1955 PRICE 10 CENT] Fifty-Two Entries For Silver Skates Wilmington, the skating mad town of Massachusetts, has a total Miss Evelyn Shepherd, of Chestnut of fifty two entries. In the Silver street will be another contestant Skates, to be held In Boston Gar- to watch. MOTHERS MARCH THURSDAY NIGHT den, next Sunday, From Jean Ash- It will be the first time that the Thursday, at 7 p.m., Wilmington worth, North American Champion, pretty lass from Chestnut St. has will have its annual Mother's down. In every class. Wilmington appeared on the Ice In Boston, but March Against Polio. Porch lights will be represented. those who watched her perform- will be lit, all over town, as house- One out of sixteen of the contest- ance at the Wilmington Skating holders signal the ladies that there ants appearing on the ice will be Carnival, last Saturday and Sun- is a contribution awaiting within. from Wilmington. A total of 822 day, believe that she is ready to About 80 ladies, in charge of a have been registered, according to take home a prise. committee headed by Mrs. Nicho- the Boston Record, but is doubt- Also appearing wiU be Officer las De Felice, Mrs. John Tautges ful if any town has as many repre- George "Boo" Shepard, of the Wil- and Mrs. Anthony Meads, will sentatives as has Wilmington. mington Police Department. participate in the march. -

Box File No. Title Location Aca

BOX FILE NO. TITLE LOCATION A.C.A. Newsletter. Alberta Composers' Association Newsletter. Alberta A.S.O. Atlantic Symphony Orchestra. Newfoundland, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia …. Nova Scotia …. [Atlantic Provinces] A Benefit Concert for Women's College Hospital. John Arpin, [Pianist.]. Women's College Hospital 75th Anniversary, Toronto. 1911-1986. Roy Thomson Hall, Toronto. 1 1 A Space - Toronto. Toronto 1 2 L'Acadamie Des Lettres Et Des Sciences Humaine de la Society Royal Du Canada. [Ottawa?] 1 3 Academy of Dance. [Brantford, Ontario?] Acadia University. Wolfville, Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia 1 4 ACME Theatre Company. Toronto Acting Company. Toronto. Toronto 1 5 The Actors Workshop. Toronto. Toronto John Adams. New Music for synthesizers, solo bass and grand pianos by John Adams & Chan Ka Nin. Premiere Dance Toronto. Theatre. New Music Concert. [Toronto.] 1 6 Adelaide Court Theatre. Toronto. Toronto 1 7 The Aeolian Town Hall. The London School Of Church Music. A Concert to honour the Silver Jubilee of Her Majesty London, Ontario Queen Elizabeth II. 1 8 Aetna Canada Young People's Concerts. Toronto. Toronto African Theatre Ensemble. Toronto 1 9 AfriCanadian Playwrights Festival. Toronto. Toronto 1 10 Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Kingston. Kingston Aid to Artists. The Canada Council, 1978-79. Ottawa. Ottawa Air Command Band. Winnipeg 1 11 Alberta College. Alberta The Alberta Music Conference. Banff School of Fine Arts. Alberta 1 12 The Aldeburgh Connection. Concert Society. Toronto. Toronto Lenore Alford, orgue. Conseil Des Arts et Des Lettres Du Quebec. Quebec 1 13 Algoma Fall Festival. Saulte Ste. Marie, Ontario. Saulte Ste. Marie, Ontario Alianak Theatre. -

DIG London Gerald & Marlene Fagan Dollirium

Issue 26 November 2011 1 DIG London Gerald & Marlene Fagan Dollirium 2 November, 2011 3 contents theatre November 2011 4 Tech Beat Chris Loblaw – DIGing London tech 6 Visual Arts Beth Stewart – A sense of place Bringing Music to Life! 8On Stage Carolyn Dolny-Guerin – Chicago 10 Q & A Daniela DiStefano – Q&A with Carey Toane music IN THE SHADOW OF MAHLER Masterwwoorrkks 1212 News & Views Phil McLeod – Test-driving public engagement udel November 12 - 8pm / Centennial Hall 1414 Words Herman Goodden – Th e birth of Wednesday’s Child in Tr 1616 Indie Dawn Lyons – Dollirium Ala Maestrro AAllaiain Trududele hoonouo rrss thehe grereaatt Mahhlleer with AdagieƩo froom ththe 5th Syymmpphhoony (the music froom ScSco 1818 Feature Nicole Laidler – Th e Fagans: A life in music Moir & Tessaa Virtutue’e s OOllyymmppicc-GGold performmannce); anndd morre 2020 Health Track Lisa Shackelton & David Fife – On track to family fi tness featturing SoSopranno Maarriaannnne Fisete . 22 Industry Mila Petkovic – Celebrating 30 years of CHRW 24 Sound Bites Bob Klanac – Alanna Gurr- It’s the voice artsvisual festivals a nz Classical Beat a 26 Nicole Laidler – November Notes L Catthhedral MUSIC & THE MONARCHY Art on the Arts Art Fidler – Th e power of community Joe 3030 November 16 - 8pm / St. Paul’s Cathedral 32 Pegg’s World Robert Pegg – Retromania at Th e Hyland Need more WWilll andd Kaattee? Joso epph Lanzn a offers uuss music thaat 3434 Final Frame London through the lens of Karen Bailey celebrrata es rooyaallttyy, iincluddini g a suuite froom Handell’s beloved WWater MuMussic & Hayayddn’s greeata La Reine Syymphony. -

Kingston Heirloom Quilters

KINGSTON HEIRLOOM QUILTERS NEWSLETTER, February 2013 KHQ web: quiltskingston.org/khq/ 2012/2013 Executive Life Members: Diane Berry, Bea Walroth, Claire Upton, Donna Hamilton President: Donna Hamilton, Anjali Shyam Past President: Simone Lynch Vice President: Corresponding Secretary: Sally Hutson Recording Secretary: Gail Jennings Treasurer: Eleanor Clark Social Convenors: Diane Davies, Gail Jennings Membership/Phone Convenors: Margaret Henshaw Publicity: Peggy McAskill Program: Executive Newsletter Editor: Ros Hanes Historian: Jocelyne Ezard Librarian: Lorna Grice Baby Quilts: Joan Bales, Peggy McAskill Meeting Dates: Tuesdays: Thursdays: Feb 21 - workday; José will give instructions for table runner workshop Mar 5 - SAQA Trunk Show with Bethany Garner, Mar 21 - José table runner workshop, workday workday Apr 5 - workday Apr 18 - workday May 7 - workday May 23 - Annual General Meeting, workday June 4 - Potluck lunch June 20 - workday Co-Presidents’ Message Anjali Shyam (and Donna Hamilton) Hope everyone stayed warm this winter. Even though it has been quite unpredictable, we did get a few snowstorms that kept us indoors, happily quilting. I hibernate when it’s that cold. I envy those who migrate (like Rosalie). The Wonky Log-cabin workshop by Mary Catherine Robb was a success. We all completed one block during the meeting. It was challenging to choose the fabric. Thanks to Mary Catherine’s February 2013 1 donated fabric scrap and also fabric donated by Jessie Deslauriers. Peggy brought in her wonky-block quilt top that looked so vibrant with all the fabric. It is interesting how such workshops inspire us to modify our own styles, choosing fabric and colour out of our comfort zones. -

Bealart City Symposium Gilder's Design

Issue 30 March 2012 Bealart City Symposium Gilder’s Design thebeatmagazine.ca | 1 March, 2012 contents theatre March 2012 4 On Stage Robyn Israel – 24 Hours of creativity 6Visual Arts Beth Stewart – 40 years of Brush & Palette Bringing Music to Life! 8 Industry Paula Schuck – City Symposium: Shaping our city’s future 1010 Q&A Nicole Laidler – Q&A with Donald D’Haene music FROM AUSTRIA WITH LOVE 1212 News & Views Phil McLeod – City Hall: Coming to a neighbourhood near you Mastere wwoorkks 1414 Feature Jill Ellis – Bealart in the air March 10 - 8pm / Centennial Hall ker Spotlight Jay Menard – Best face forward r 16 a Threr e ggianntss of sysympmphohoniic wwrriƟnng; yet eaeach strugglg eedd in n P 1818 Sound Bites Bob Klanac – Liam Isaac Ia Viennana… Exxpep rir enence thhee drraamma, beaauty andd elegancce aas Alaiin Trudel connduducts SScchhubert’s crowwnniing orchesstral 2020 Classical Beat Nicole Laidler – Video to Verdi creaƟon, “The GrG eaeatt”” Symmphony.y Iaann Parker maakes his 22 Art on the Arts Art Fidler – Life with shows artsvisual festivals Orchestra Londdoonn deebbutu on Moozazart’’s Piano Connccerto No. 20! 2424 Pegg’s World Robert Pegg – Eating the old 2626 Final Frame London through the lens of Deborah Zuskan A TRIBUTE TO MICHAEL JACKSON RRed Hoot Weeeke enndss OnO the cover: Ceris Thomas raises a glass to The Drowsy Chaperone. March 23 & 24 - 8pm / Centennial Hall StStory on page 10. Photo by Ross Davidson. OOrchc esstrtra LLonndonn & The Jeans ‘n CClassiccs band honour MiM chhaea l JJackkssoonn’’s iincreddiiblee 40--yey ar legacy, from his OnlineO features @ www.thebeatmagazine.ca DISHingDI with Donald | What’s On? | Contests & Promotions | Rants & Raves bbegig nnnninngs as a yyouth ssttarr of the Jackkson Five, thror ugh hiis monnuummeental Thhriller yyears aand later hiitts. -

OUR LIST of WINTER &SPRING 2021 GRADUATES Medals and Awards

OUR LIST OF WINTER &SPRING 2021 GRADUATES Medals and Awards Governor-General’s Medal (Graduate) Amir TAHERIDEHKORDI Governor-General’s Medal (Undergraduate) Reilly Heith SMITH 2 University Medal for Academic Excellence in Archaeology Andrew KENNEY Behavioural Neuroscience Olivia Elizabeth BARRETT Biochemistry Reilly Heith SMITH Biochemistry (Nutrition) Olivia Elizabeth BARRETT Biology Jenna Barbara TILLEY Business Administration Hind Rached FAIAD Business Administration (Grenfell Campus) Patti Samantha RICKETTS 3 University Medal for Academic Excellence in Chemistry William Trent BURGESS Classics Eric Patrick RICHARD Communication Studies Sophie Elyse CUTLER Computer Science Troy Joseph Anthoney PFINDER Earth Sciences David Joseph DROVER Economics Daniel Clarence MOORE Post-Secondary Education Sara SHEEHAN 4 University Medal for Academic Excellence in Primary/Elementary Education Carla Marie BARTLETT Music Education Alison Joy CLARKE Civil Engineering Hayley Elizabeth ROGERS Computer Engineering Matthew Joseph HICKEY Electrical Engineering Mark Scott BELBIN Mechanical Engineering Marcus Joseph BERKSHIRE Ocean and Naval Architectural Engineering Joshua Louis VEBER 5 University Medal for Academic Excellence in Process Engineering Noah James GRIFFITHS English (Grenfell Campus) Muhammad Nadhiir Farhaar KURMOO English Simon Todd TAYLOR Environmental Science (Grenfell Campus) Natalie Loretta Irene PARSONS French Lacy Nicholle CUSTANCE Geography Laura Elizabeth CADIGAN German Samantha Elizabeth TUCK 6 University Medal for Academic Excellence