FOOLS and Philosophers: Piccolomini's Comedic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plautus, with an English Translation by Paul Nixon

'03 7V PLAUTUS. VOLUMK I. AMPHITRYON. THE COMEDY OF ASSES. THE POT OF GOLD. THE TWO BACCHISES. THE CAPTIVES. Volume II. CASIXA. THE CASKET COMEDY. CURCULIO. EPIDICUS. THE TWO MENAECHMUSES. THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY EDITED BY E. CAPPS, PH.])., LL.J1. T. E. PAGE, litt.d. ^V. H. D. ROUSE, LiTT.D. PLAUTUS III "TTTu^^TTr^cJcuTr P L A U T U S LVvOK-..f-J WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY PAUL NIXON PROFESSOR OF LATIN, BOWDOIS COLLEGE, UAINE IN FIVE VOLUMES III THE MERCHANT THE BRAGGART WARRIOR THE HAUNTED HOUSE THE PERSIAN LONDON : WILLIAM HEINEMANN NEW YORK : G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS MCMXXIV Printed in Great Britain THE GREEK ORIGINALS AND DATES OF THE PLAYS IN THE THIRD VOLUME The Mercator is an adaptation of Philemon's Emporos}- When the Emporos was produced^ how- ever, is unknown, as is the date of production of the Mercator, and of the Mosldlaria and Perm, as well. The Alason, the Greek original of the Milex Gloriosus, was very likely written in 287 B.C., the argument ^ for that date being based on interna- tional relations during the reign of Seleucus,^ for whom Pyrgopolynices was recruiting soldiers at Ephesus. And Periplectomenus's allusion to the imprisonment of Naevius* might seem to suggest that Plautus composed the Miles about 206 b.c. Philemon's Fhasma was probably the original of the Mostellaria, and written, as it apparently was, after the death of Alexander the Great and Aga- thocles,^ we may assume that Philemon presented the Phasma between 288 b.c. and the year of the death of Diphilus,^ who was living when it was produced. -

Plautus, with an English Translation by Paul Nixon

^-< THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY I FOUKDED BY JAMES IXtEB, liL.D. EDITED BY G. P. GOOLD, PH.D. FORMEB EDITOBS t T. E. PAGE, C.H., LiTT.D. t E. CAPPS, ph.d., ii.D. t W. H. D. ROUSE, LITT.D. t L. A. POST, l.h.d. E. H. WARMINGTON, m.a., f.b.hist.soc. PLAUTUS IV 260 P L A U T U S WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY PAUL NIXON DKAK OF BOWDODf COLUDOB, MAin IN FIVE VOLUMES IV THE LITTLE CARTHAGINIAN PSEUDOLUS THE ROPE T^r CAMBRIDOE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD MCMLXXX American ISBN 0-674-99286-5 British ISBN 434 99260 7 First printed 1932 Reprinted 1951, 1959, 1965, 1980 v'Xn^ V Wbb Printed in Great Britain by Fletcher d- Son Ltd, Norwich CONTENTS I. Poenulus, or The Little Carthaginian page 1 II. Pseudolus 144 III. Rudens, or The Rope 287 Index 437 THE GREEK ORIGINALS AND DATES OF THE PLAYS IN THE FOURTH VOLUME In the Prologue^ of the Poenulus we are told that the Greek name of the comedy was Kapx^Sdvios, but who its author was—perhaps Menander—or who the author of the play which was combined with the Kap;^8ovios to make the Poenulus is quite uncertain. The time of the presentation of the Poenulus at ^ Rome is also imcertain : Hueffner believes that the capture of Sparta ' was a purely Plautine reference to the war with Nabis in 195 b.c. and that the Poenulus appeared in 194 or 193 b.c. The date, however, of the Roman presentation of the Pseudolus is definitely established by the didascalia as 191 b.c. -

Near-Miss Incest in Plautus' Comedies

“I went in a lover and came out a brother?” Near-Miss Incest in Plautus’ Comedies Although near-miss incest and quasi-incestuous woman-sharing occur in eight of Plautus’ plays, few scholars treat these themes (Archibald, Franko, Keyes, Slater). Plautus is rarely rec- ognized as engaging serious issues because of his bawdy humor, rapid-fire dialogue, and slap- stick but he does explore—with humor—social hypocrisies, slave torture (McCarthy, Parker, Stewart), and other discomfiting subjects, including potential social breakdown via near-miss incest. Consummated incest in antiquity was considered the purview of barbarians or tyrants (McCabe, 25), and was a common charge against political enemies (e.g. Cimon, Alcibiades, Clo- dius Pulcher). In Greek tragedy, incest causes lasting catastrophe (Archibald, 56). Greece fa- vored endogamy, and homopatric siblings could marry (Cohen, 225-27; Dziatzko; Harrison; Keyes; Stärk), but Romans practiced exogamy (Shaw & Saller), prohibiting half-sibling marriage (Slater, 198). Roman revulsion against incestuous relationships allows Plautus to exploit the threat of incest as a means of increasing dramatic tension and exploring the degeneration of the societies he depicts. Menander provides a prototype. In Perikeiromene, Moschion lusts after a hetaera he does not know is his sister, and in Georgos, an old man seeks to marry a girl who is probably his daughter. In both plays, the recognition of the girl’s paternity prevents incest and allows her to marry the young man with whom she has already had sexual relations. In Plautus’ Curculio a soldier pursues a meretrix who is actually his sister; in Epidicus a girl is purchased as a concu- bine by her half-brother; in Poenulus a foreign father (Blume) searches for his daughters— meretrices—by hiring prostitutes and having sex with them (Franko) while enquiring if they are his daughters; and in Rudens where an old man lusts after a girl who will turn out to be his daughter. -

PONTEM INTERRUMPERE: Plautus' CASINA and Absent

Giuseppe pezzini PONTEM INTERRUMPERE : pLAuTus’ CASINA AnD ABsenT CHARACTeRs in ROMAn COMeDY inTRODuCTiOn This article offers an investigation of an important aspect of dramatic technique in the plays of plautus and Terence, that is the act of making reference to characters who are not present on stage for the purpose of plot, scene and theme development (‘absent characters’). This kind of technique has long been an object of research for scholars of theatre, especially because of the thematization of its dramatic potential in the works of modern playwrights (such as strindberg, ibsen, and Beckett, among many others). extensive research, both theoretical and technical, has been carried out on several theatrical genres, and especially on 20 th -century American drama 1. Ancient Greek tragedy has recently received attention in this respect also 2. Less work has been done, however, on another important founding genre of western theatre, the Roman comedy of plautus and Terence, a gap due partly to the general neglect of the genre in the second half of the 20 th century, in both scholarship and reception (with some important exceptions). This article contributes to this area of theatre research by pre - senting an overview of four prototypical functions of ‘absent characters’ in Roman comedy (‘desired’, ‘impersonated’, ‘licensing’ and ‘proxied’ absentees), along with a discussion of their metatheatrical potential and their close connection archetypal in - gredients of (Roman) comedy. i shall begin with a dive into plautus’ Casina ; this play features all of what i shall identify as the ‘prototypes’ of absent characters in comedy, which will be discussed in the first part of this article (sections 1-5). -

Theodore Harry Mcmillan Gellar

SACRIFICE AND RITUAL IMAGERY IN MENANDER, PLAUTUS, AND TERENCE Theodore Harry McMillan Gellar A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Classics. Chapel Hill 2008 APPROVED BY: Sharon L. James, advisor James B. Rives, reader Peter M. Smith, reader © 2008 Theodore Harry McMillan Gellar ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Theodore Harry McMillan Gellar SACRIFICE AND RITUAL IMAGERY IN MENANDER, PLAUTUS, AND TERENCE (Under the direction of Sharon L. James) This thesis offers a systematic analysis of sacrifice and ritual in New Comedy. Sacri- fice normally signifies a healthy community, often celebrating a family reunification. Men- ander, Plautus, and Terence treat sacrifice remarkably, each in a different way. In Menander, sacrifice seals the formation of healthy citizen marriages; in Plautus, it operates to negotiate theatrical power between characters. When characters use sacrificial imagery, they are es- sentially asserting authority over other characters or agency over the play. Both playwrights mark habitual sacrificers, particularly citizen females, as morally upright. Terence, by con- trast, stunningly withholds sacrifice altogether, to underscore the emotional dysfunction among the citizen classes in hisplays. Chapter 1 sets sacrifice in its historical and theatrical context. Chapter 2 considers how sacrifice might have been presented onstage; chapter 3 examines its theatrical functions. Chapter 4 focuses on gender and status issues, and chapter 5 moves out from sacrifice to rit- ual and religion overall. iii τῷ φίλῳ καί µοι ἐγγυηκότι optimis parentibus iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I have endless gratitude first of all for Sharon James, my advisor, mentor, and role model, without whom my thesis simply could not be. -

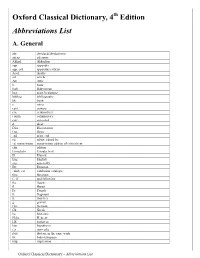

Abbreviations List A

Oxford Classical Dictionary, 4th Edition Abbreviations List A. General abr. abridged/abridgement adesp. adespota Akkad. Akkadian app. appendix app. crit. apparatus criticus Aeol. Aeolic art. article Att. Attic b. born Bab. Babylonian beg. at/nr. beginning bibliog. bibliography bk. book c. circa cent. century cm. centimetre/s comm. commentary corr. corrected d. died Diss. Dissertation Dor. Doric end at/nr. end ed. editor, edited by ed. maior/minor major/minor edition of critical text edn. edition Einzelschr. Einzelschrift El. Elamite Eng. English esp. especially Etr. Etruscan exhib. cat. exhibition catalogue fem. feminine f., ff. and following fig. figure fl. floruit Fr. French fr. fragment ft. foot/feet g. gram/s Ger. German Gk. Greek ha. hectare/s Hebr. Hebrew HS sesterces hyp. hypothesis i.a. inter alia ibid. ibidem, in the same work IE Indo-European imp. impression Oxford Classical Dictionary – Abbreviations List in. inch/es introd. introduction Ion. Ionic It. Italian kg. kilogram/s km. kilometre/s lb. pound/s l., ll. line, lines lit. literally lt. litre/s L. Linnaeus Lat. Latin m. metre/s masc. masculine mi. mile/s ml. millilitre/s mod. modern MS(S) manuscript(s) Mt. Mount n., nn. note, notes n.d. no date neut. neuter no. number ns new series NT New Testament OE Old English Ol. Olympiad ON Old Norse OP Old Persian orig. original (e.g. Ger./Fr. orig. [edn.]) OT Old Testament oz. ounce/s p.a. per annum PIE Proto-Indo-European pl. plate plur. plural pref. preface Proc. Proceedings prol. prologue ps.- pseudo- Pt. part ref. reference repr. -

Introducing Geminate Writing: Plautus' Miles Gloriosus

Vasiliki Kella Introducing geminate writing: Plautus’ Miles Gloriosus Abstract The purpose of this paper is to examine how the theme of the Double is presented in Plautus’ Miles Gloriosus . Underneath the obvious relation between the doubling and comedies like Miles Gloriosus , there is something more systematic about this method that deserves to be explored. ‘Geminate writing’ acquires a multileveled dynamics in Plautus’ comic language, characters, plot and performance. We discuss the expression hoc argumentum sicilicissitat which is proved to denote the gemination of plots and characters. We are then led to see the gemination of staging. The device of doubles and twins and the story of a dream cause the stage to split into two mirroring halves. We focus on the skenographia and we see the temporary stage and its structure, the physical format of which creates mirror reflections. The paper is divided into three parts, covering the textual, theatrical and performance levels of Miles Gloriosus , respectively. Lo scopo di questo studio è quello di esaminare il modo in cui viene presentato il tema del doppio nel Miles Gloriosus di Plauto. Sotto la relazione evidente tra il raddoppio e commedie come il Miles Gloriosus , c'è qualcosa di più sistematico in questo metodo che merita di essere esplorato. ‘Geminate writing’ riguarda dinamiche multilivello su linguaggio, personaggi e intreccio comico di Plauto. Viene presa in esame la frase hoc argumentum sicilicissitat che indica la duplicazione di trame e personaggi. In seguito viene analizzata la duplicazione di scena. Il dispositivo di doppio e la storia di un sogno dividono infatti la scena stessa in due metà speculari. -

Funny Things Happened in Roman Comedy

Funny Things Happened in Roman Comedy Teacher’s Manual and Text Nelson Berry UGA Summer Institute, 2015 Table of Contents Purpose and Development.............................................................................................................i Suggested Syllabus .......................................................................................................................i Introduction to Roman Comedy Greek Origins ...................................................................................................................ii Roman Theater and Comedy ............................................................................................ii Stereotypical Characters ..................................................................................................iii Common Themes and Situations ......................................................................................v Plautus’ Works and Style .................................................................................................vi Guidelines and Rubrics for Student Projects ................................................................................ix Sample Quiz for Pseudolus ..........................................................................................................xii Selected Readings from Plautus Pseudolus ...........................................................................................................................1 Miles Gloriosus ................................................................................................................30 -

Son and Daughters, Love and Marriage: on the Plots and Priorities of Roman Comedy

Son and Daughters, Love and Marriage: On the Plots and Priorities of Roman Comedy Roman Comedy is often described as aiming for marriage. Such is the masterplot of Greek New Comedy, and more than a few Roman plays end up with at least an arranged union. Thus, the standard plot description for a Roman comedy begins with “boy loves girl” and ends with “boy gets girl.” In between, there is usually something about a clever slave or parasite. Thus Feeney (2010: 284) says of Pseudolus that its “fundamental plot resembles virtually every other Plautine plot—boy has met girl but cannot have her, but finally does get her thanks to cunning slave.” This description, which rightly recognizes the crucial role of the clever slave in Plautus’ theater, summarizes a long-standing view found in other sources too numerous to list. But this summary is fundamentally incorrect. It fits only six of Plautus’ plays: Asinaria, Bacchides, Miles, Mostellaria, Poenulus, Pseudolus, and none of Terence’s, where the clever slave plays a reduced, often ineffective role. Fourteen Plautine plays have no such plot: Amphitruo, Aulularia, Captivi, Casina, Cistellaria, Curculio, Epidicus, Menaechmi, Mercator, Persa, Rudens, Stichus, Trinummus, and Truculentus. (Most of these do not even have a clever slave.) Even substitution of clever parasite for clever slave adds only two more plays, Curculio and Persa. As for the marriage-masterplot, Plautus’ plays often do not end in marriage: Asinaria, Bacchides, Mercator, Miles, Mostellaria, Persa, and Pseudolus cannot end in marriage—the beloved is a meretrix, not a lost daughter; in Persa the lover is a slave himself. -

AN INTRODUCTION to PLAUTUS THROUGH SCENES Selected And

AN INTRODUCTION TO PLAUTUS THROUGH SCENES Selected and Translated by Richard F. Hardin ‘Title page for Titus Maccius Plautus, Comoediae Superstites XX, 1652’ Lowijs Elzevier (publisher) Netherlands (Amsterdam); 1652 - The Rijksmuseum © Copyright 2021, Richard F. Hardin, All Rights Reserved. Please direct enquiries for commercial re-use to [email protected] Published by Poetry in Translation (https://poetryintranslation.com) This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply: https://poetryintranslation.com/Admin/Copyright.php 1 Preface This collection celebrates a comic artist who left twenty plays written during the decades on either side of 200 B.C. He spun his work from Greek comedies, “New Comedies” bearing his own unique stamp.1 In Rome the forerunners of such plays, existing a generation before Plautus, were called fabulae palliatae, comedies in which actors wore the Greek pallium or cloak. These first situation comedies, Greek then Roman, were called New Comedies, in contrast with the more loosely plotted Old Comedies, surviving in the plays of Aristophanes. The jokes, characters, and plots that Plautus and his successor Terence left have continued to influence comedy from the Renaissance even to the present. Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors, Taming of the Shrew, Merry Wives of Windsor, and The Tempest are partly based on Menaechmi, Amphitruo, Mostellaria, Casina, and Rudens; Molière’s L’Avare (The Miser), on Aulularia; Gelbart and Sondheim’s A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, on Pseudolus, Miles Gloriosus, Casina, and Mostellaria; David Williamson’s Flatfoot (2004) on Miles Gloriosus; the Capitano in Commedia dell’Arte, Shakespeare’s Falstaff, and Jonson’s Bobadill all inherit traits of Plautus’s braggart soldiers. -

Turn Taking and Power Relations in Plautus' Casina

Graeco-Latina Brunensia 25 / 2020 / 1 https://doi.org/10.5817/GLB2020-1-2 Turn taking and power relations in Plautus’ Casina Łukasz Berger (Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań) Abstract The paper interprets the verbal behaviour of pater familias and his subordinates in Plautus’ Casina through the lenses of conversation analysis and im/politeness research. According to the approach here presented, turn-allocating techniques can function as a means of depicting ČLÁNKY / ARTICLES power relationships – whether presupposed or emergent and negotiated on-stage – among high- and low-status characters in Roman comedies. The analysed data draw a connection be- tween the active initiating of the dialogue, the management of the turn space, and speakership rights (e.g. silencing through the directive tace) with the dominant social position, prototypi- cally of high-born men. The authority of Roman slave-owners, reproduced in the characteri- sation of the senex, has been viewed in relation to potestas, the Roman conceptualisation of default social dominance. On the other hand, the subordinate role of slaves arguably is gov- erned by quasi-mandatory patterns of linguistic use interpreted as politic behaviour which – in interaction with free-born citizens – consisted of obedience, withdrawal, lack of initiative, and deprivation of face. Keywords Plautus; Casina; turn taking; im/politeness; power; pater familias; silence; greeting The paper is part of the international research project “Conversation in Antiquity. Analysis of Verbal Inter- action in Ancient Greek and Latin” (SI1/PJI/2019-00283), financed by the Community of Madrid. I want to express my gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful suggestions and corrections. -

The Stichïïs Op Plautus

1 ‘'THE STICHÏÏS OP PLAUTUS: An Introduction and Elementary Commentary" A LISSERTATIOU Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the University of London by JEANETTE DEIRDRE COOK Bedford College, December, 1965 ProQuest Number: 10097283 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10097283 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT This dissertation is composed of two parts» The Introduction comprises sections on Comedy in general, on Plautus's life, on the metres and the manuscripts of his plays » With the exception of the section on the structure of the Stichus, it is a restatement of the situation as generally accepted by scholars today. The question of the structure of the Stichus is still a matter of contention, and the leading views on this subject have been discussed critically in this section» The Commentary is intended for the level of an undergraduate reader and comprises notes on grammar, syntax and general interpretation» The more detailed points concerning the metre are also discussed in the notes.