Turn Taking and Power Relations in Plautus' Casina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plautus, with an English Translation by Paul Nixon

'03 7V PLAUTUS. VOLUMK I. AMPHITRYON. THE COMEDY OF ASSES. THE POT OF GOLD. THE TWO BACCHISES. THE CAPTIVES. Volume II. CASIXA. THE CASKET COMEDY. CURCULIO. EPIDICUS. THE TWO MENAECHMUSES. THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY EDITED BY E. CAPPS, PH.])., LL.J1. T. E. PAGE, litt.d. ^V. H. D. ROUSE, LiTT.D. PLAUTUS III "TTTu^^TTr^cJcuTr P L A U T U S LVvOK-..f-J WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY PAUL NIXON PROFESSOR OF LATIN, BOWDOIS COLLEGE, UAINE IN FIVE VOLUMES III THE MERCHANT THE BRAGGART WARRIOR THE HAUNTED HOUSE THE PERSIAN LONDON : WILLIAM HEINEMANN NEW YORK : G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS MCMXXIV Printed in Great Britain THE GREEK ORIGINALS AND DATES OF THE PLAYS IN THE THIRD VOLUME The Mercator is an adaptation of Philemon's Emporos}- When the Emporos was produced^ how- ever, is unknown, as is the date of production of the Mercator, and of the Mosldlaria and Perm, as well. The Alason, the Greek original of the Milex Gloriosus, was very likely written in 287 B.C., the argument ^ for that date being based on interna- tional relations during the reign of Seleucus,^ for whom Pyrgopolynices was recruiting soldiers at Ephesus. And Periplectomenus's allusion to the imprisonment of Naevius* might seem to suggest that Plautus composed the Miles about 206 b.c. Philemon's Fhasma was probably the original of the Mostellaria, and written, as it apparently was, after the death of Alexander the Great and Aga- thocles,^ we may assume that Philemon presented the Phasma between 288 b.c. and the year of the death of Diphilus,^ who was living when it was produced. -

Plautus, with an English Translation by Paul Nixon

^-< THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY I FOUKDED BY JAMES IXtEB, liL.D. EDITED BY G. P. GOOLD, PH.D. FORMEB EDITOBS t T. E. PAGE, C.H., LiTT.D. t E. CAPPS, ph.d., ii.D. t W. H. D. ROUSE, LITT.D. t L. A. POST, l.h.d. E. H. WARMINGTON, m.a., f.b.hist.soc. PLAUTUS IV 260 P L A U T U S WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY PAUL NIXON DKAK OF BOWDODf COLUDOB, MAin IN FIVE VOLUMES IV THE LITTLE CARTHAGINIAN PSEUDOLUS THE ROPE T^r CAMBRIDOE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD MCMLXXX American ISBN 0-674-99286-5 British ISBN 434 99260 7 First printed 1932 Reprinted 1951, 1959, 1965, 1980 v'Xn^ V Wbb Printed in Great Britain by Fletcher d- Son Ltd, Norwich CONTENTS I. Poenulus, or The Little Carthaginian page 1 II. Pseudolus 144 III. Rudens, or The Rope 287 Index 437 THE GREEK ORIGINALS AND DATES OF THE PLAYS IN THE FOURTH VOLUME In the Prologue^ of the Poenulus we are told that the Greek name of the comedy was Kapx^Sdvios, but who its author was—perhaps Menander—or who the author of the play which was combined with the Kap;^8ovios to make the Poenulus is quite uncertain. The time of the presentation of the Poenulus at ^ Rome is also imcertain : Hueffner believes that the capture of Sparta ' was a purely Plautine reference to the war with Nabis in 195 b.c. and that the Poenulus appeared in 194 or 193 b.c. The date, however, of the Roman presentation of the Pseudolus is definitely established by the didascalia as 191 b.c. -

Near-Miss Incest in Plautus' Comedies

“I went in a lover and came out a brother?” Near-Miss Incest in Plautus’ Comedies Although near-miss incest and quasi-incestuous woman-sharing occur in eight of Plautus’ plays, few scholars treat these themes (Archibald, Franko, Keyes, Slater). Plautus is rarely rec- ognized as engaging serious issues because of his bawdy humor, rapid-fire dialogue, and slap- stick but he does explore—with humor—social hypocrisies, slave torture (McCarthy, Parker, Stewart), and other discomfiting subjects, including potential social breakdown via near-miss incest. Consummated incest in antiquity was considered the purview of barbarians or tyrants (McCabe, 25), and was a common charge against political enemies (e.g. Cimon, Alcibiades, Clo- dius Pulcher). In Greek tragedy, incest causes lasting catastrophe (Archibald, 56). Greece fa- vored endogamy, and homopatric siblings could marry (Cohen, 225-27; Dziatzko; Harrison; Keyes; Stärk), but Romans practiced exogamy (Shaw & Saller), prohibiting half-sibling marriage (Slater, 198). Roman revulsion against incestuous relationships allows Plautus to exploit the threat of incest as a means of increasing dramatic tension and exploring the degeneration of the societies he depicts. Menander provides a prototype. In Perikeiromene, Moschion lusts after a hetaera he does not know is his sister, and in Georgos, an old man seeks to marry a girl who is probably his daughter. In both plays, the recognition of the girl’s paternity prevents incest and allows her to marry the young man with whom she has already had sexual relations. In Plautus’ Curculio a soldier pursues a meretrix who is actually his sister; in Epidicus a girl is purchased as a concu- bine by her half-brother; in Poenulus a foreign father (Blume) searches for his daughters— meretrices—by hiring prostitutes and having sex with them (Franko) while enquiring if they are his daughters; and in Rudens where an old man lusts after a girl who will turn out to be his daughter. -

PONTEM INTERRUMPERE: Plautus' CASINA and Absent

Giuseppe pezzini PONTEM INTERRUMPERE : pLAuTus’ CASINA AnD ABsenT CHARACTeRs in ROMAn COMeDY inTRODuCTiOn This article offers an investigation of an important aspect of dramatic technique in the plays of plautus and Terence, that is the act of making reference to characters who are not present on stage for the purpose of plot, scene and theme development (‘absent characters’). This kind of technique has long been an object of research for scholars of theatre, especially because of the thematization of its dramatic potential in the works of modern playwrights (such as strindberg, ibsen, and Beckett, among many others). extensive research, both theoretical and technical, has been carried out on several theatrical genres, and especially on 20 th -century American drama 1. Ancient Greek tragedy has recently received attention in this respect also 2. Less work has been done, however, on another important founding genre of western theatre, the Roman comedy of plautus and Terence, a gap due partly to the general neglect of the genre in the second half of the 20 th century, in both scholarship and reception (with some important exceptions). This article contributes to this area of theatre research by pre - senting an overview of four prototypical functions of ‘absent characters’ in Roman comedy (‘desired’, ‘impersonated’, ‘licensing’ and ‘proxied’ absentees), along with a discussion of their metatheatrical potential and their close connection archetypal in - gredients of (Roman) comedy. i shall begin with a dive into plautus’ Casina ; this play features all of what i shall identify as the ‘prototypes’ of absent characters in comedy, which will be discussed in the first part of this article (sections 1-5). -

Theodore Harry Mcmillan Gellar

SACRIFICE AND RITUAL IMAGERY IN MENANDER, PLAUTUS, AND TERENCE Theodore Harry McMillan Gellar A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Classics. Chapel Hill 2008 APPROVED BY: Sharon L. James, advisor James B. Rives, reader Peter M. Smith, reader © 2008 Theodore Harry McMillan Gellar ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Theodore Harry McMillan Gellar SACRIFICE AND RITUAL IMAGERY IN MENANDER, PLAUTUS, AND TERENCE (Under the direction of Sharon L. James) This thesis offers a systematic analysis of sacrifice and ritual in New Comedy. Sacri- fice normally signifies a healthy community, often celebrating a family reunification. Men- ander, Plautus, and Terence treat sacrifice remarkably, each in a different way. In Menander, sacrifice seals the formation of healthy citizen marriages; in Plautus, it operates to negotiate theatrical power between characters. When characters use sacrificial imagery, they are es- sentially asserting authority over other characters or agency over the play. Both playwrights mark habitual sacrificers, particularly citizen females, as morally upright. Terence, by con- trast, stunningly withholds sacrifice altogether, to underscore the emotional dysfunction among the citizen classes in hisplays. Chapter 1 sets sacrifice in its historical and theatrical context. Chapter 2 considers how sacrifice might have been presented onstage; chapter 3 examines its theatrical functions. Chapter 4 focuses on gender and status issues, and chapter 5 moves out from sacrifice to rit- ual and religion overall. iii τῷ φίλῳ καί µοι ἐγγυηκότι optimis parentibus iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I have endless gratitude first of all for Sharon James, my advisor, mentor, and role model, without whom my thesis simply could not be. -

Loeb Classical Library

LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY 2017–2018 Founded by JAMES LOEB 1911 Edited by JEFFREY HENDERSON NEW TITLES FRAGMENTARY GALEN REPUBLICAN LATIN Hygiene Ennius EDITED AND TRANSLATED BY EDITED AND TRANSLATED BY IAN JOHNSTON • SANDER M. GOLDBERG Galen of Pergamum (129–?199/216), physician GESINE MANUWALD to the court of the emperor Marcus Aurelius, Quintus Ennius (239–169 BC), widely was a philosopher, scientist, medical historian, regarded as the father of Roman literature, theoretician, and practitioner who wrote on an was instrumental in creating a new Roman astonishing range of subjects and whose literary identity and inspired major impact on later eras rivaled that of Aristotle. developments in Roman religion, His treatise Hygiene, also known social organization, and popular as “On the Preservation of Health” culture. This two-volume edition (De sanitate tuenda), was written of Ennius, which inaugurates during one of Galen’s most prolific the Loeb series Fragmentary periods (170–180) and ranks among Republican Latin, replaces that his most important and influential of Warmington in Remains of Old works, providing a comprehensive Latin, Volume I and offers fresh account of the practice of texts, translations, and annotation preventive medicine that still that are fully current with modern has relevance today. scholarship. L535 Vol. I: Books 1–4 2018 515 pp. L294 Vol. I: Ennius, Testimonia. L536 Vol. II: Books 5–6. Thrasybulus. Epic Fragments 2018 475 pp. On Exercise with a Small Ball L537 Vol. II: Ennius, Dramatic 2018 401 pp. Fragments. Minor Works 2018 450 pp. APULEIUS LIVY Apologia. Florida. De Deo Socratis History of Rome EDITED AND TRANSLATED BY EDITED AND TRANSLATED BY CHRISTOPHER P. -

FOOLS and Philosophers: Piccolomini's Comedic

Cynthia Liu FOOLS anD PhiLOSOPhERS: PiCCOLOMini’S COMEDiC RESPOnSE tO LuCREtiuS Drama of the Quattrocento was generally imitative of the tragedies of Seneca and comedies of Plautus and terence 1. By the end of that century, the plays of these two playwrights were being performed and recited frequently. yet until 1429, only eight plays of Plautus were known to italian humanists 2. in that year Poggio Brac - ciolini and nicolaus Cusanus’ discovery of the codex ursinianus, now housed in the Vatican library, added twelve more 3. they were immediately popular and an editio princeps , edited by Giorgio Merula, was soon published in Venice 4. it was in this context that Enea Silvio Piccolomini wrote his Latin comedy, Chrysis. unlike his humanistic novel Historia de Duobus Amantibus , which remained in circu - lation despite being rejected by Pius ii, Chrysis lay forgotten in a Prague library until the nineteenth century, but safe in its obscurity from Pius ii’s suppression of his erotic works. Composed between 26 august 1444 and the end of September the same year, the play provides a terminus post que m: it mentions in lines 160-163 the bat - tle of St. Jakob an der Birs, which took place on 26 august 1444. a terminus ante quem is derived from the date (1 October 1444) of Piccolomini’s letter to Michael Pful - lendorf, the chief clerk in the emperor’s court, in which he responds to Pfullendorf’s criticism of that play: “you scorn not only the poem but also the poet. and accuse me, who wrote the comedy, of being cheap, as if terence and Plautus, who also wrote comedies, had not been praised” 5. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/79116 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-30 and may be subject to change. Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2009.07.03 Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2009.07.03 David Christenson (ed.), Plautus: Four Plays. Casina, Amphitryon, Captivi, Pseudolus. Focus Classical Library. Newburyport, MA: Focus Publishing, 2008. Pp. 265. ISBN 9781585101559. $14.95 (pb). Reviewed by Vincent Hunink, Radboud University Nijmegen ([email protected]) Word count: 1233 words Until relatively recently, the archaic Roman comedies of Plautus (ca. 254-184 B.C.) used to find little favour with classical scholars. His plays were often labelled rude and primitive, lacking in dramatic finesse and psychology, aiming at easy success with his audience, without much sense for serious, moral values. The poet earned some praise, meanwhile, for the liveliness of his works, which offer a unique insight into daily life in early Rome, and for his creative use of the Latin language. In recent years, by contrast, Plautus has been given much attention and he seems to have become almost fashionable among liberal-minded scholars. For example, English translations of some Plautine plays were published by Amy Richlin (2006) and John Henderson (2007), which each in their own way could be described as radical and postmodern (I reviewed both books in BMCR 2006.05.35 and 2007.01.03 respectively). Obviously in reaction to such trends in Plautine studies, David Christenson has now published a new translation of four comedies by Plautus that aims to steer a middle course between translations that "seemed either ineptly stilted or too far removed from Plautus' Latin and his culture", and between "accuracy and liveliness" (p. -

Loeb Classical Libary Titles

Middlebury College Classics Department Library Catalog: Loeb Classical Library Titles - Sorted by Author Publish Title Subtitle Author Translator Language Binding Pages Date A. S. Hunt Select Papyri I, Non-Literary Loeb Classical A. S. Hunt & C. Ancient (Editor) & C. C. 06/01/1932 Hardcover 472 Papyri, Private Affairs Library, No. 266 C. Edgar Greek/English Edgar (Editor) A. S. Hunt Select Papyri II, Non-Literary Loeb Classical A. S. Hunt & C. Ancient (Editor) & C. C. 06/01/1934 Hardcover 0 Papyri, Public Documents Library, No. 282 C. Edgar Greek/English Edgar (Editor) Loeb Classical Ancient Historical Miscellany Aelian Nigel Guy Wilson 06/01/1997 Hardcover 520 Library, No. 486 Greek/English On the Characteristics of Loeb Classical Ancient Aelian A. F. Scholfield 06/01/1958 Hardcover 400 Animals I, Books I-V Library, No. 446 Greek/English On the Characteristics of Loeb Classical Ancient Aelian A. F. Scholfield 06/01/1958 Hardcover 432 Animals II, Books VI-XI Library, No. 448 Greek/English On the Characteristics of Loeb Classical Ancient Aelian A. F. Scholfield 06/01/1958 Hardcover 464 Animals III, Books XII-XVII Library, No. 449 Greek/English The Speeches of Aeschines, Loeb Classical Charles Darwin Ancient Against Timarchus, On The Aeschines 06/01/1919 Hardcover 552 Library, No. 106 Adams Greek/English Embassy, Against Ctesiphon Aeschylus I, Suppliant Maidens, Persians, Loeb Classical Herbert Weir Ancient Aeschylus 12/01/1970 Hardcover 464 Prometheus, Seven Against Library, No. 145 Smyth Greek/English Thebes Aeschylus II, Agamemnon, Loeb Classical Aeschylus Herbert Weir Ancient 06/01/1960 Hardcover 624 Publish Title Subtitle Author Translator Language Binding Pages Date Libation-Bearers, Eumenides, Library, No. -

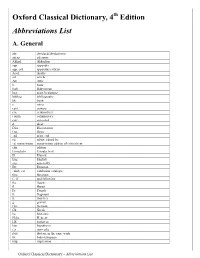

Abbreviations List A

Oxford Classical Dictionary, 4th Edition Abbreviations List A. General abr. abridged/abridgement adesp. adespota Akkad. Akkadian app. appendix app. crit. apparatus criticus Aeol. Aeolic art. article Att. Attic b. born Bab. Babylonian beg. at/nr. beginning bibliog. bibliography bk. book c. circa cent. century cm. centimetre/s comm. commentary corr. corrected d. died Diss. Dissertation Dor. Doric end at/nr. end ed. editor, edited by ed. maior/minor major/minor edition of critical text edn. edition Einzelschr. Einzelschrift El. Elamite Eng. English esp. especially Etr. Etruscan exhib. cat. exhibition catalogue fem. feminine f., ff. and following fig. figure fl. floruit Fr. French fr. fragment ft. foot/feet g. gram/s Ger. German Gk. Greek ha. hectare/s Hebr. Hebrew HS sesterces hyp. hypothesis i.a. inter alia ibid. ibidem, in the same work IE Indo-European imp. impression Oxford Classical Dictionary – Abbreviations List in. inch/es introd. introduction Ion. Ionic It. Italian kg. kilogram/s km. kilometre/s lb. pound/s l., ll. line, lines lit. literally lt. litre/s L. Linnaeus Lat. Latin m. metre/s masc. masculine mi. mile/s ml. millilitre/s mod. modern MS(S) manuscript(s) Mt. Mount n., nn. note, notes n.d. no date neut. neuter no. number ns new series NT New Testament OE Old English Ol. Olympiad ON Old Norse OP Old Persian orig. original (e.g. Ger./Fr. orig. [edn.]) OT Old Testament oz. ounce/s p.a. per annum PIE Proto-Indo-European pl. plate plur. plural pref. preface Proc. Proceedings prol. prologue ps.- pseudo- Pt. part ref. reference repr. -

Introducing Geminate Writing: Plautus' Miles Gloriosus

Vasiliki Kella Introducing geminate writing: Plautus’ Miles Gloriosus Abstract The purpose of this paper is to examine how the theme of the Double is presented in Plautus’ Miles Gloriosus . Underneath the obvious relation between the doubling and comedies like Miles Gloriosus , there is something more systematic about this method that deserves to be explored. ‘Geminate writing’ acquires a multileveled dynamics in Plautus’ comic language, characters, plot and performance. We discuss the expression hoc argumentum sicilicissitat which is proved to denote the gemination of plots and characters. We are then led to see the gemination of staging. The device of doubles and twins and the story of a dream cause the stage to split into two mirroring halves. We focus on the skenographia and we see the temporary stage and its structure, the physical format of which creates mirror reflections. The paper is divided into three parts, covering the textual, theatrical and performance levels of Miles Gloriosus , respectively. Lo scopo di questo studio è quello di esaminare il modo in cui viene presentato il tema del doppio nel Miles Gloriosus di Plauto. Sotto la relazione evidente tra il raddoppio e commedie come il Miles Gloriosus , c'è qualcosa di più sistematico in questo metodo che merita di essere esplorato. ‘Geminate writing’ riguarda dinamiche multilivello su linguaggio, personaggi e intreccio comico di Plauto. Viene presa in esame la frase hoc argumentum sicilicissitat che indica la duplicazione di trame e personaggi. In seguito viene analizzata la duplicazione di scena. Il dispositivo di doppio e la storia di un sogno dividono infatti la scena stessa in due metà speculari. -

Magidenko, Maria 2018 Classics Thesis Title

Magidenko, Maria 2018 Classics Thesis Title: Love is an Open Door: The Paraclausithyron in Plautus: Advisor: Edan Dekel Advisor is Co-author: None of the above Second Advisor: Released: release now Contains Copyrighted Material: No Love is an Open Door: The Paraclausithyron in Plautus by MARIA ESTELLA MAGIDENKO Edan Dekel, Advisor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in Classics WILLIAMS COLLEGE Williamstown, MA April 30, 2018 Acknowledgements I first would like to thank Professor Amanda Wilcox, who introduced me to Plautus in the spring of my junior year. When I became interested in Plautus’s use of doors in his plays, she encouraged me to pursue the topic further through this thesis. Without Professor Wilcox’s support, the idea for this thesis would not have been developed. Next I would like to thank Professor Edan Dekel, who agreed without hesitation to be my thesis advisor the same day I walked into his office to introduce myself and pitch my thesis idea. He has been supportive and thoughtful, always available to suggest new sources and ideas, and advise me not only on my thesis topic, but also about the Classics at large and other subjects of interest in general. Without his guidance, this thesis would not have come to fruition, nor its writing been the enjoyable experience that it was. I am grateful to the entire Williams College Classics department, particularly Professors Kerry Christensen and Kenneth Draper, whose wisdom and support have been crucial to my development as a student of the Classics, and to Professor Emerita Meredith Hoppin, whose guidance during my first year of Latin was without equal.