Bill Vaughn's Incredible Butt-Kicking Machine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MEDIA INFORMATION Astros.Com

Minute Maid Park 2016 HOUSTON ASTROS 501 Crawford St Houston, TX 77002 713.259.8900 MEDIA INFORMATION astros.com Houston Astros 2016 season review ABOUT THE 2016 RECORD in the standings: The Astros finished 84-78 year of the whiff: The Astros pitching staff set Overall Record: .............................84-78 this season and in 3rd place in the AL West trailing a club record for strikeouts in a season with 1,396, Home Record: ..............................43-38 the Rangers (95-67) and Mariners (86-76)...Houston besting their 2004 campaign (1,282)...the Astros --with Roof Open: .............................6-6 went into the final weekend of the season still alive ranked 2nd in the AL in strikeouts, while the bullpen --with Roof Closed: .......................37-32 in the playoff chase, eventually finishing 5.0 games led the AL with 617, also a club record. --with Roof Open/Closed: .................0-0 back of the 2nd AL Wild Card...this marked the Astros Road Record: ...............................41-40 2nd consecutive winning season, their 1st time to throw that leather: The Astros finished the Series Record (prior to current series): ..23-25-4 Sweeps: ..........................................10-4 post back-to-back winning years since the 2001-06 season leading the AL in fielding percentage with When Scoring 4 or More Runs: ....68-24 seasons. a .987 clip (77 errors in 6,081 total chances)...this When Scoring 3 or Fewer Runs: ..16-54 marked the 2nd-best fielding percentage for the club Shutouts: ..........................................8-8 tale of two seasons: The Astros went 67-50 in a single season, trailing only the 2008 Astros (.989). -

THE Monday Lecture Traces Fall and Rise of Harley-Davidson

~---- ----------------------- --~---- Smoke gets in your eyes Stupid freshmen? Before you light up. take a look at Transfer student Mike Marchand draws the Monday Scene's report on of the deadly effects line when it comes to defining freshmen of nicotine. at Notre Dame. SEPTEMBER 13, page 12 page 11 1999 THE The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's VOL XXXIII NO. 15 HTTP://OBSERVER.ND.EDU Students, corporations connect at business career forum West Life, adding that lw alrnady • Fair offers had a few snrious candidates chances to meet after one evening of collecting resunws. industry recruiters The Friday afternoon sessions w1~re morn casual. as business students roamed the forum to By LAURA SEGURA get a feel !'or the current job N<·w,Wrirn market. Students took advantage of the networking opportunities A sea of suits and ties lloodml for summer internships and tem tlw Collegn of Business porary positions. Administration last W!Hlk as Whiln some underclassmen Notn~ llanw business students just canw to look, many juniors mf't with had a specific rPprPsPnta "Last year I just came lo objectivo in tivPs from mind. morP than gel free pens, but this year "Last year I I 00 rom pa I'm serious. " just came to get n iPs at thP free pens, but a 11 n u a I this year I'm COllA CarPPr Jascint Vukelich serious," said Forum. junior business major junior Jaseint Tlw forum Vukelich, who welcomPd a came to the widr1 range forum in of companies to set up informa snarch of an internship in invest tional booths and n~cruit the nwnt banking. -

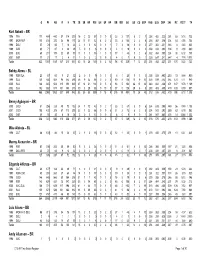

C12 Batter Register03

GPA AB R H TB 2B 3B HR RBI SH SF HP BB IBB SO SB CS GDP AVG SLG OBP 2AV RC RC27 TA Kurt Abbott – BR 1996 TAY 117 484 442 57 114 200 16 2 22 57 0 0 9 33 2 127 5 2 7 .258 .452 .322 .281 65 5.18 .733 1997 MOR-FER 113 416 375 34 96 175 24 11 11 52 4 2 2 33 4 120 2 4 6 .256 .467 .318 .304 54 4.98 .734 1998 DOU 57 74 65 7 18 23 3 1 0 12 0 1 1 7 3 18 0 0 2 .277 .354 .351 .185 8 4.35 .633 1999 AVD 60 71 67 4 24 29 5 0 0 6000 4 01904 3.358 .433 .394 .134 9 4.80 .660 2000 EVE 69 201 183 22 59 83 13 1 3 16 1 0 0 17 1 48 0 2 6 .322 .454 .380 .224 30 6.02 .758 2001 SKR 17 21 17 3 4 11 1 0 2 2000 4 0 7 00 1.235 .647 .381 .647 4 7.74 1.071 Totals 433 1267 1149 127 315 521 62 15 38 145 5 3 12 98 10 339 7 12 25 .274 .453 .337 .271 170 5.22 .732 Bobby Abreu – BL 1998 FER-SLA 25 67 60 9 21 32 2 0 3 9010 6 12001 0.350 .533 .403 .283 13 8.64 .950 1999 SLA 145 660 568 96 182 295 29 9 22 96 0 2 0 90 8 156 15 9 13 .320 .519 .412 .384 123 8.11 .980 2000 SLA 146 665 563 115 193 339 27 13 31 116 0 5 4 93 5 102 26 10 22 .343 .602 .436 .471 147 9.76 1.149 2002 SLA 152 668 571 101 153 276 30 3 29 88 0 10 0 87 0 126 29 6 8 .268 .483 .359 .419 108 6.59 .907 Totals 468 2060 1762 321 549 942 88 25 85 309 0 18 4 276 14 404 70 26 43 .312 .535 .402 .419 390 8.10 1.008 Benny Agbayani – BR 2000 COO 81 256 225 45 73 138 24 1 13 42 0 2 1 28 3 67 8 0 6 .324 .613 .398 .449 56 9.49 1.108 2001 COO 108 435 378 67 115 205 22 1 22 68 0 0 6 51 2 73 6 2 8 .304 .542 .395 .389 83 8.19 .982 2002 SKR 45 50 42 6 16 28 3 0 3 10 0 0 0 8 0 9 0 0 1 .381 .667 .480 .476 14 13.84 1.333 Totals 234 -

Houston Astros 2017 Season Review

Houston Astros 2017 season review ABOUT THE regular season final results: With a 101-61 record, the Astros measuring up: The Astros finished the season with Overall Record: ...........................101-61 won the AL West division by 21 games over the Angels, the second-best record in the American League, just Home Record (MMP only): ...........47-31 marking the largest division win in franchise history... 1.0 game behind the Cleveland Indians (102-60)...final --with Roof Open: .............................8-6 Houston’s 101 wins are their second-highest total in AL and MLB standings below: --with Roof Closed: .......................39-25 club history, trailing a 102-60 record, set in 1998. al leaders GB mlb leaders GB --with Roof Open/Closed: .................0-0 most wins in astros history Indians (102-60) - Dodgers (104-58) - Road Record: ...............................53-28 1. 1998: 102-60 3. 1999: 97-65 T5. 2001: 93-69 Astros (101-61) 1.0 Indians (102-60) 2.0 Series Record: ...........................34-14-3 2. 2017: 101-61 4. 1996: 96-66 T5. 1980: 93-70 Red Sox (93-69) 9.0 Astros (101-61) 3.0 Sweeps: ..........................................12-3 When Scoring 4 or More Runs: ....83-22 When Scoring 3 or Fewer Runs: ..18-39 rewriting the record books: The Astros got off teamwork: The Astros have 10 players with 50-plus Shutouts: ..........................................9-5 to a scorching start to the season, at one point owning RBI and eight players with 15-plus home runs, both In One-Run Games: .....................19-13 a 42-16 record after an 11-game winning streak on franchise records...the Astros are just the fourth team In Two-Run Games: .....................16-17 June 5...Houston set a franchise record with their best in Major League history to have 10-plus players collect vs. -

April 1, 2021 at Wrigley Field, Chicago, IL -- GAME #1/ROAD #1 RHP CHAD KUHL (2-3, 4.27 ERA in 2020) Vs

PITTSBURGH PIRATES (0-0) vs. CHICAGO CUBS (0-0) April 1, 2021 at Wrigley Field, Chicago, IL -- GAME #1/ROAD #1 RHP CHAD KUHL (2-3, 4.27 ERA in 2020) vs. RHP KYLE HENDRICKS (6-5, 2.88 ERA in 2020) IT’S THE MOST WONDERFUL TIME OF THE YEAR: Today the Pirates begin their 135th season of professional baseball in the National League...The Bucs have produced a 71-63 record in their first 134 openers (55-48 on the road and 16-15 at home)...The Pirates lost a 5-4 decision to the Cardinals in St. Louis on Opening Day last year. BUCS WHEN... OPENING ON THE ROAD: The Bucs are opening the season on the road for the fifth straight year and for the sixth time in the Last five games ................0-0 last seven years...The Pirates have now opened the regular season on the road 103 times, compared to just 32 times on their home turf...Since 2007, the Pirates have posted an 8-6 record in their last 14 season openers. Last ten games .................0-0 NO FOOLIN’: The Pirates are opening the regular season at Wrigley Field for the first time since April 1, 2011...Kevin Correia Leading after 6 .................0-0 was the Bucco starter and winner that afternoon in a 6-3 victory over Ryan Dempster and Joel Hanrahan picked up the save... Neil Walker connected off Dempster for a grand slam in the fifth inning; the second one in team history that has been hit on Tied after 6 ....................0-0 Opening Day...Game time temperature that day was 41 degrees with rainy conditions. -

Debut Year Player Hall of Fame Item Grade 1871 Doug Allison Letter

PSA/DNA Full LOA PSA/DNA Pre-Certified Not Reviewed The Jack Smalling Collection Debut Year Player Hall of Fame Item Grade 1871 Doug Allison Letter Cap Anson HOF Letter 7 Al Reach Letter Deacon White HOF Cut 8 Nicholas Young Letter 1872 Jack Remsen Letter 1874 Billy Barnie Letter Tommy Bond Cut Morgan Bulkeley HOF Cut 9 Jack Chapman Letter 1875 Fred Goldsmith Cut 1876 Foghorn Bradley Cut 1877 Jack Gleason Cut 1878 Phil Powers Letter 1879 Hick Carpenter Cut Barney Gilligan Cut Jack Glasscock Index Horace Phillips Letter 1880 Frank Bancroft Letter Ned Hanlon HOF Letter 7 Arlie Latham Index Mickey Welch HOF Index 9 Art Whitney Cut 1882 Bill Gleason Cut Jake Seymour Letter Ren Wylie Cut 1883 Cal Broughton Cut Bob Emslie Cut John Humphries Cut Joe Mulvey Letter Jim Mutrie Cut Walter Prince Cut Dupee Shaw Cut Billy Sunday Index 1884 Ed Andrews Letter Al Atkinson Index Charley Bassett Letter Frank Foreman Index Joe Gunson Cut John Kirby Letter Tom Lynch Cut Al Maul Cut Abner Powell Index Gus Schmeltz Letter Phenomenal Smith Cut Chief Zimmer Cut 1885 John Tener Cut 1886 Dan Dugdale Letter Connie Mack HOF Index Joe Murphy Cut Wilbert Robinson HOF Cut 8 Billy Shindle Cut Mike Smith Cut Farmer Vaughn Letter 1887 Jocko Fields Cut Joseph Herr Cut Jack O'Connor Cut Frank Scheibeck Cut George Tebeau Letter Gus Weyhing Cut 1888 Hugh Duffy HOF Index Frank Dwyer Cut Dummy Hoy Index Mike Kilroy Cut Phil Knell Cut Bob Leadley Letter Pete McShannic Cut Scott Stratton Letter 1889 George Bausewine Index Jack Doyle Index Jesse Duryea Cut Hank Gastright Letter -

2001 Topps Baseball Card Set Checklist

2001 TOPPS BASEBALL CARD SET CHECKLIST 1 Cal Ripken Jr. 2 Chipper Jones 3 Roger Cedeno 4 Garret Anderson 5 Robin Ventura 6 Daryle Ward 8 Craig Paquette 9 Phil Nevin 10 Jermaine Dye 11 Chris Singleton 12 Mike Stanton 13 Brian R. Hunter 14 Mike Redmond 15 Jim Thome 16 Brian Jordan 17 Joe Girardi 18 Steve Woodard 19 Dustin Hermanson 20 Shawn Green 21 Todd Stottlemyre 22 Dan Wilson 23 Todd Pratt 24 Derek Lowe 25 Juan Gonzalez 26 Clay Bellinger 27 Jeff Fassero 28 Pat Meares 29 Eddie Taubensee 30 Paul O'Neill 31 Jeffrey Hammonds 32 Pokey Reese 33 Mike Mussina 34 Rico Brogna 35 Jay Buhner 36 Steve Cox 37 Quilvio Veras 38 Marquis Grissom 39 Shigetoshi Hasegawa 40 Shane Reynolds 41 Adam Piatt 42 Luis Polonia 43 Brook Fordyce Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 44 Preston Wilson 45 Ellis Burks 46 Armando Rios 47 Chuck Finley 48 Dan Plesac 49 Shannon Stewart 50 Mark McGwire 51 Mark Loretta 52 Gerald Williams 53 Eric Young 54 Peter Bergeron 55 Dave Hansen 56 Arthur Rhodes 57 Bobby Jones 58 Matt Clement 59 Mike Benjamin 60 Pedro Martinez 61 Jose Canseco 62 Matt Anderson 63 Torii Hunter 64 Carlos Lee 65 David Cone 66 Rey Sanchez 67 Eric Chavez 68 Rick Helling 69 Manny Alexander 70 John Franco 71 Mike Bordick 72 Andres Galarraga 73 Jose Cruz Jr. 74 Mike Matheny 75 Randy Johnson 76 Richie Sexson 77 Vladimir Nunez 78 Harold Baines 79 Aaron Boone 80 Darin Erstad 81 Alex Gonzalez 82 Gil Heredia 83 Shane Andrews 84 Todd Hundley 85 Bill Mueller 86 Mark McLemore 87 Scott Spiezio 88 Kevin McGlinchy 89 Bubba Trammell 90 Manny Ramirez Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 2 91 Mike Lamb 92 Scott Karl 93 Brian Buchanan 94 Chris Turner 95 Mike Sweeney 96 John Wetteland 97 Rob Bell 98 Pat Rapp 99 John Burkett 100 Derek Jeter 101 J.D. -

Download the PDF of the Baseball Research Journal, Volume 31

CONTENTS John McGraw Comes to NewYork by Clifford Blau ~3 56-Game Hitting Streaks Revisited by Michael Freiman 11 Lou vs. Babe in'Real Life and inPride ofthe Yankees by Frank Ardolino 16 The Evolution ofWorld Series Scheduling by Charlie Bevis 21 BattingAverage by Count and Pitch 1YPe by J. Eric Bickel & Dean Stotz 29 HarryWright by Christopher Devine 35 International League RBI Leaders by David F. Chrisman 39 Identifying Dick Higham by Harold Higham 45 Best ofTimes, Worst ofTimes by Scott Nelson 51 Baseball's Most Unbreakable Records by Joe Dittmar 54 /Ri]] Ooak's Three "No-Hitters" by Stephen Boren , , , , , ,62 TIle Kiltg is Dead by Victor Debs 64 Home Runs: More Influential Than Ever by Jean-Pierre Caillault , 72 The Most Exciting World Series Games by Peter Reidhead & Ron Visco 76 '~~"" The Best __."..II ••LlI Team Ever? David Surdam 80 Kamenshek, the All-American by John Holway 83 Most Dominant Triple CrownWinner by Vince Gennaro '.86 Preventing Base Hits by Dick Cramer , , , ,, , , , 88 Not Quite Marching Through Georgia by Roger Godin 93 Forbes Field, Hitter's Nightmare? by Ron SeIter 95 RBI, Opportunities, and Power Hitting by Cyril Morong 98 Babe Ruth Dethroned? by Gabe Costa 102 Wanted: One First-Class Shortstop by Robert Schaefer 107 .; Does Experiellce Help ill tIle Post-Season? by Tom Hanrahan ' 111 jThe Riot at the FirstWorld Series by Louis P. Masur 114 Why Isn't Gil Hodges In the Hall ofFame? by John Saccoman It ••••••••••••••••••••••••118 From a Researcher's Notebook by AI Kermisch ' 123 EDITOR'S NOTE I believe that this thirty-first issue of the Baseball Research Journal has something for everyone: controversy, nostalgia, origi nality, mystery-even a riot. -

Houston Astros 2020 Season in Review

2 0 2 0 H O U S T O N A S T R O S M I N U T E M A I D PA R K • 5 01 C R A W F O R D S T. • H O U S T O N , T X 770 0 2 • 713. 259. 8 9 0 0 • A S T R O S .C O M HOUSTON ASTROS 2020 SEASON IN REVIEW ABOUT THE REGULAR SEASON POSTSEASON APPEARANCES: The Astros are LIMITING K’S: Astros hitters combined for the few- Overall Record: .............................29-31 making their 14th appearance in the postseason in est strikeouts in the Majors with 440 on the season... Home Record: ................................20-8 club history in what is the 59th year of the franchise this is a commonplace for this group of Astros, as the --with Roof Open: .............................0-0 that began in 1962...this season marks the fourth in club had the fewest strikeouts in the AL in 2017 and --with Roof Closed: .........................20-8 club history for the Astros to enter the postseason as 2019, while finishing with the second fewest in 2018. --with Roof Open/Closed: .................0-0 a non-division winner, previously doing so as a Wild Road Record: .................................9-23 Card winner in 2004, 2005 and in 2015. QUICK STARTS: The Astros led the AL in 1st-inning Current Streak: ............................ Lost 3 runs, posting a healthy 47 runs in their 1st innings, Last Homestand: ..............................4-2 FOUR STRAIGHT: The Astros secured their post- besting the Yankees (42) and Mariners (42) in that Last Road Trip: .................................2-5 Last 5 Games: ..................................1-4 season spot by finishing second in the AL West...this category...CF George Springer was the catalyst for Last 10 Games: ................................4-6 appearance gives Houston four straight years in the this, posting a 1.008 OPS in his 50 1st-inning plate Series Record (prior to current series): ....11-8-1 playoffs, the first time they’ve done so in franchise his- appearances this season, which included three leadoff Sweeps: ............................................4-4 tory...only the Yankees and Dodgers have also played homers. -

Houston Astros (51-110) Vs. New York Yankees (84-77) LHP Erik Bedard (4-12, 4.81) Vs

Houston Astros (51-110) vs. New York Yankees (84-77) LHP Erik Bedard (4-12, 4.81) vs. LHP David Huff (3-1, 5.16) Saturday, Sept. 29, 2013 • Minute Maid Park • Houston, TX • 1:10 p.m. CT • CSN Houston GAME #162 ..............HOME #81 FINAL STAND: Today is the season finale for STANDING TALL: Jose Altuve’s 41 hits in Sep- ABOUT THE RECORD the Astros and Yankees as they play a 1:10 p.m. tember are the 3rd-highest total for the month Overall Record: ....................51-110 matinee at Minute Maid Park. in franchise history, trailing Richard Hidalgo Home Record: ........................24-56 (49-2000) and Cesar Cedeno (1977)...Altuve --with Roof Open: .....................3-11 MO HONORED: The Astros will recognize currently ranks 1st in the Majors in hits (41) and --with Roof Closed: .................21-45 Mariano Rivera’s standout career with a pregame 1st in the AL in batting with a .373 clip (41x110)... Road Record: ..........................27-54 ceremony today...Rivera’s former manager Joe he has four three-hit games and one four-hit Current Streak: .................... Lost 14 Torre, and his former Astros and Yankees team- game in Sept. Current Homestand: .................. 0-2 mate Roger Clemens, are scheduled to partici- FOR SEPTEMBER Recent Road Trip: ...................... 0-7 pate in the ceremony along with Astros President Most Hits - MBL Highest AVG - AL Last 5 Games: ............................ 0-5 Reid Ryan. 1. J. Altuve - 41 1. J. Altuve - .373 Last 10 Games: .........................0-10 2. M. Carpenter - 38 2. M. Brantley .363 Series Record: .....................11-39-2 ASTROS-YANKEES: The Astros are 1-4 vs. -

Houston Astros (41-85) Vs

Houston Astros (41-85) vs. Toronto Blue Jays (57-71) RHP Jordan Lyles (5-6, 5.19) vs. RHP Todd Redmond (1-1, 3.32) Friday, August 23, 2013 • Minute Maid Park • Houston, TX • 7:10 p.m. • CSN GAME #127 ..............HOME #63 HOME QUICKIE: Beginning tonight, the Astros HISTORIC START: RHP Jarred Cosart has had ABOUT THE RECORD will host the Toronto Blue Jays this weekend in one of the best starts to his career in franchise Overall Record: ......................41-85 what is a brief, 3-game homestand...the Astros history (source: Elias): Home Record: ........................19-43 were off yesterday following a 9-game road trip, *has pitched at least 5.0 innings and allowed no --with Roof Open: .....................3-11 on which they finished 4-5, going 2-1 at both OAK more than three runs in his first seven Major League --with Roof Closed: .................16-32 and LAA and 0-3 at TEX, respectively. starts...the only other pitcher in Astros history to Road Record: ..........................22-42 hold this distinction in his first seven MLB starts was Current Streak: ...................... Lost 3 VS. TORONTO: The current series will mark just LHP Mike Maddon, who’s streak ended at seven for Last Homestand: ........................ 1-6 the 2nd visit ever to Houston for the Blue Jays... the 1983 Astros. Recent Road Trip: ...................... 4-5 Rude Hosts: The Astros swept a 3-game series *has the lowest ERA (1.60) by a starter thru their first Last 5 Games: ............................ 1-4 from TOR at Minute Maid Park in their 1st visit, seven starts in franchise history...that distinction was Last 10 Games: ......................... -

Final 2001 Golden Bay Rotisserie League Standings

2001 GOLDEN BAY ROTISSERIE LEAGUE BASEBALL STANDINGS Includes All Games Played Through October 8, 2001 HITTING Home Runs Runs Batted In Batting Average Stolen Bases ARTFUL DODGERS 274 JEFFREY LOADERS 990 GARDEN PARTIERS .2816 SLEEPING DOGS 143 GARDEN PARTIERS 265 ARTFUL DODGERS 952 KNOTH BALLS .2781 MICHAEL'S MAULTERS 130 JEFFREY LOADERS 265 GARDEN PARTIERS 947 ARTFUL DODGERS .2770 KNOTH BALLS 128 ROSS DRESS FOR LESS 243 ROSS DRESS FOR LESS 893 ROSS DRESS FOR LESS .2763 ROSS DRESS FOR LESS 114 MICHAEL'S MAULTERS 237 WILLIAM'S CONQUERORS 893 JEFFREY LOADERS .2735 ARTFUL DODGERS 107 WILLIAM'S CONQUERORS 230 MICHAEL'S MAULTERS 844 WILLIAM'S CONQUERORS .2727 TOM'S THUMBS 106 SLEEPING DOGS 212 JIM RUMMIES 800 SLEEPING DOGS .2725 MEYER'S FLYERS 105 KNOTH BALLS 194 KNOTH BALLS 771 MEYER'S FLYERS .2706 WILLIAM'S CONQUERORS 101 TOM'S THUMBS 189 SLEEPING DOGS 770 MICHAEL'S MAULTERS .2702 JEFFREY LOADERS 97 JIM RUMMIES 184 TOM'S THUMBS 731 ROBIN HOODS .2634 GARDEN PARTIERS 95 ROBIN HOODS 184 MEYER'S FLYERS 701 JIM RUMMIES .2626 JIM RUMMIES 78 MEYER'S FLYERS 171 ROBIN HOODS 700 TOM'S THUMBS .2601 ROBIN HOODS 76 PITCHING Wins Saves Earned Run Average Ratio MICHAEL'S MAULTERS 96 GARDEN PARTIERS 63 ARTFUL DODGERS 3.784 ROBIN HOODS 1.2506 ROBIN HOODS 88 JEFFREY LOADERS 63 ROBIN HOODS 3.912 ARTFUL DODGERS 1.3008 ARTFUL DODGERS 87 ROBIN HOODS 62 ROSS DRESS FOR LESS 3.913 ROSS DRESS FOR LESS 1.3115 WILLIAM'S CONQUERORS 86 KNOTH BALLS 61 KNOTH BALLS 4.045 JEFFREY LOADERS 1.3228 JEFFREY LOADERS 81 ARTFUL DODGERS 60 MICHAEL'S MAULTERS 4.099 WILLIAM'S CONQUERORS