Download the PDF of the Baseball Research Journal, Volume 31

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ticket Stubs Alone Have Little Value

Ticket stubs alone have little value Jeff Figler can be reached at [email protected]. He would be glad to give you his opinion on values of sports collectibles. BY JEFF FIGLER SPECIAL TO THE POST-DISPATCH 02/17/2010 Every so often I am asked if there is value to ticket stubs, or even unused full tickets. In short, the answer is no. The only instances in which ticket stubs or unused tickets are of value is if they are related to significant events, and only if they are auctioned with other related items. A ticket stub to, let's say a game in July 1962 has no value, except to the owner of the stub. (Maybe going to the game was a birthday gift.) However, a ticket stub to a game of historical significance, for example, Game 7 of the 1960 World Series between the New York Yankees and the Pittsburgh Pirates, would have some value. If you combine the ticket stub from that game, with a program from that game, newspaper clippings, and a team-signed ball of the 1960 Pirates, then you have a nice package, worth a minimum of $500. Of course, the value will depend on the condition of the items, especially of the baseball, and if there happened to be a bidding war on that lot. In case you might have forgotten, Game 7 of the 1960 World Series was the one in which statistically the Yankees dominated, but the Bucs won the Series on a walk-off homer by Bill Mazeroski. If someone has the entire unused ticket of a particular event, not merely the ticket stub, the value goes up a bit, but not dramatically. -

Reign Men Taps Into a Compelling Oral History of Game 7 in the 2016 World Series

Reign Men taps into a compelling oral history of Game 7 in the 2016 World Series. Talking Cubs heads all top CSN Chicago producers need in riveting ‘Reign Men’ By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Thursday, March 23, 2017 Some of the most riveting TV can be a bunch of talking heads. The best example is enjoying multiple airings on CSN Chicago, the first at 9:30 p.m. Monday, March 27. When a one-hour documentary combines Theo Epstein and his Merry Men of Wrigley Field, who can talk as good a game as they play, with the video skills of world-class producers Sarah Lauch and Ryan McGuffey, you have a must-watch production. We all know “what” happened in the Game 7 Cubs victory of the 2016 World Series that turned from potentially the most catastrophic loss in franchise history into its most memorable triumph in just a few minutes in Cleveland. Now, thanks to the sublime re- porting and editing skills of Lauch and McGuffey, we now have the “how” and “why” through the oral history contained in “Reign Men: The Story Behind Game 7 of the 2016 World Series.” Anyone with sense is tired of the endless shots of the 35-and-under bar crowd whooping it up for top sports events. The word here is gratuitous. “Reign Men” largely eschews those images and other “color” shots in favor of telling the story. And what a tale to tell. Lauch and McGuffey, who have a combined 20 sports Emmy Awards in hand for their labors, could have simply done a rehash of what many term the greatest Game 7 in World Series history. -

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Wednesday, July 1, 2020 * The Boston Globe College lefties drafted by Red Sox have small sample sizes but big hopes Julian McWilliams There was natural anxiety for players entering this year’s Major League Baseball draft. Their 2020 high school or college seasons had been cut short or canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. They lost that chance at increasing their individual stock, and furthermore, the draft had been reduced to just five rounds. Lefthanders Shane Drohan and Jeremy Wu-Yelland felt some of that anxiety. The two were in their junior years of college. Drohan attended Florida State and Wu-Yelland played at the University of Hawaii. There was a chance both could have gone undrafted and thus would have been tasked with the tough decision of signing a free agent deal capped at $20,000 or returning to school for their senior year. “I didn’t know if I was going to get drafted,” Wu-Yelland said in a phone interview. “My agent was kind of telling me that it might happen, it might not. Just be ready for anything.” Said Drohan, “I knew the scouting report on me was I have the stuff to shoot up on draft boards but I haven’t really put it together yet. I felt like I was doing that this year and then once [the season] got shut down, that definitely played into the stress of it, like, ‘Did I show enough?’ ” As it turned out, both players showed enough. The Red Sox selected Wu-Yelland in the fourth round and Drohan in the fifth. -

105484 Mbb Mg Cvr.Id2

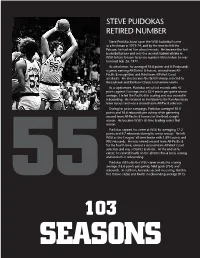

STEVE PUIDOKAS RETIRED NUMBER Steve Puidokas burst upon the WSU basketball scene as a freshman in 1973-74, and by the time he left the Palouse, he had set five school records. He became the first basketball player and only the second student-athlete in WSU history to have his jersey number retired when he was honored Feb. 26, 1977. As a freshman, he averaged 16.8 points and 8.9 rebounds a game, earning All-District 8 honors, second team All- Pacific-8 recognition and third team All-West Coast accolades. He also became the first freshman selected to the Jayhawk and Rainbow Classic tournament teams. As a sophomore, Puidokas set school records with 42 points against Gonzaga and a 22.4 points per game season average. He led the Pacific-8 in scoring and was second in rebounding. He received an invitation to the Pan-American team tryouts and was a second team All-Pac-8 selection. During his junior campaign, Puidokas averaged 18.0 points and 10.6 rebounds per outing while garnering second team All-Pacific-8 honors for the third straight season. He became WSU’s all-time leading scorer that season. Puidokas capped his career at WSU by averaging 17.2 points and 9.7 rebounds during his senior season. He left WSU as the Cougars’ all-time leader with 1,894 points and 992 rebounds. He was named second team All-Pacific-8 for the fourth time, earned a second team All-West Coast selection and was a District 8 all-star. At the end of his career, he ranked fourth on the all-time Pac-8 list in scoring and seventh in rebounding. -

Bridgeportsandmohawks Ofmeriden Clash Here Sunday

Pae Four THE BRIDGEPORT TIMES Saturday, Oct: 15, 1921 rts And Mohawks OfMeriden Clash Here Bridgepo- Sunday OUTDOOR SPORTS HERE'S A SHOCK! By Tad Football 1 LOCAL BALL CLUB ow ONLY BROKE EVEN Sport By GEORGE E. FIRSTBROOK. Monarch Although the past admissions to Nwfleld Park totaled between 80.000 ANDERSON PLEASED and 90,000 in the 1921 baseball sea- son, an increase over last season, I RGES WEIGHT LIMIT there were no mountain high profits OVER VICTORY OF according to Clark Lane, Jr., presi- FOR FOOTBALL ELEVENS dent of the Bridgeport Baseball club. 3"he guessing slats of fans who have D, H. S. RUNNERS New Haven, Oct. 13 John Heis-ma- n, been estimating the profits of the lo-c- the University of Pennsylvania club all the from $10,000 to coach and formerly of Georgia way came In The 520.000 have been badly shattered, CHICK CREATON. Tech, out today Yale according to Mr. Lane's dope. By Daily Xews favoring decision of "We managed to break about even Minus the services of six members ffkvthsll plrvon in three lnsses . and' are well satisfied," said Mr. Lane of its regular squad, through ineligi- Iieavywe-ights- middleweights and ( yesterday. bility, the Bridgeport High School Hill lightweights. The weights at which ' Albany Jumps Expensive. and Dale team easily won over the he would make the classification 'Mr. Lane explained that while the Bristol High Run yesterday afternoon are 165. 155 and 145 pounds. He ' were ex- by a score of 23-3- 2. stated that he felt that many of the htae crowds good the heavy n-n- panse involved in theMbng jumps, Matty Skane. -

The American Legion Magazine, P

LEGIOIVTHE AMERICAN 15'' lUNE 1959 MAGAZINE SEE PAGE 12 How a Gl almost stopped the Normandy inypsfoi SEE PAGE 22 AN UMPm . Play it smart: Know what you're getting in a cigarette. Know right now that what you get in a Lucky is the finest tobacco in America . the most famous taste in smoking. You get it clear through— in every Lucky. Can you say that much for the brand you're smoking now? Play it smart: Get the honest taste of a LUCKY STRIKE ©A T Co. Product of J^mfuetm tju^iaeo-^^nuia/rw — </a^meeo- is our middle name THE AMERICAN LEGION DON'T FOUR DECADES 1919-1959 OF DEDICATED SERVICE Vol. 60. No. 6; June 1059 THE AMERICAN FORGET! MAGAZINE Contents for June 1959 Cover by You can provide Benn Mitchell-Weco LUCKIES by the case HOW A Gl ALMOST STOPPED THE NORMANDY INVASION by Thomas Jeffries Betts 12 TAX-FREE (LESS THAN THE BIGGEST SECRET OF THE CENTURY WAS DROPPED IN THE MAIL. A LETTER TO NORMAN COUSINS by Frank A. Tinker 14 9< A PACK) for AN EX-POW WONDERS ABOUT SOME OF THE COUSINS CRUSADES. shipment to one or HOW TO HAVE FUN LIKE A FISH by Vlad Evanoff 16 IT IS EASY TO ENTER INTO THE UNDERWATER WORLD. all of the following THE GENIE IN YOUR GAS TANK by Clarence Woodbury 18 ALL ABOUT THE FUEL THAT KEEPS US ON THE GO. service groups: HOW TO ... by Bob Elliott and Ray Goulding 20 YOU TOO CAN BE A DO-IT-YOURSELFER, IF YOU HAVE TO. -

Handbook of Sports and Media

Job #: 106671 Author Name: Raney Title of Book: Handbook of Sports & Media ISBN #: 9780805851892 HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA LEA’S COMMUNICATION SERIES Jennings Bryant/Dolf Zillmann, General Editors Selected titles in Communication Theory and Methodology subseries (Jennings Bryant, series advisor) include: Berger • Planning Strategic Interaction: Attaining Goals Through Communicative Action Dennis/Wartella • American Communication Research: The Remembered History Greene • Message Production: Advances in Communication Theory Hayes • Statistical Methods for Communication Science Heath/Bryant • Human Communication Theory and Research: Concepts, Contexts, and Challenges, Second Edition Riffe/Lacy/Fico • Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research, Second Edition Salwen/Stacks • An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA Edited by Arthur A.Raney College of Communication Florida State University Jennings Bryant College of Communication & Information Sciences The University of Alabama LAWRENCE ERLBAUM ASSOCIATES, PUBLISHERS Senior Acquisitions Editor: Linda Bathgate Assistant Editor: Karin Wittig Bates Cover Design: Tomai Maridou Photo Credit: Mike Conway © 2006 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2009. To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk. Copyright © 2006 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microform, retrieval system, or any other means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Handbook of sports and media/edited by Arthur A.Raney, Jennings Bryant. p. cm.–(LEA’s communication series) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Major League Baseball and the Antitrust Rules: Where Are We Now???

MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL AND THE ANTITRUST RULES: WHERE ARE WE NOW??? Harvey Gilmore, LL.M, J.D.1 INTRODUCTION This essay will attempt to look into the history of professional baseball’s antitrust exemption, which has forever been a source of controversy between players and owners. This essay will trace the genesis of the exemption, its evolution through the years, and come to the conclusion that the exemption will go on ad infinitum. 1) WHAT EXACTLY IS THE SHERMAN ANTITRUST ACT? The Sherman Antitrust Act, 15 U.S.C.A. sec. 1 (as amended), is a federal statute first passed in 1890. The object of the statute was to level the playing field for all businesses, and oppose the prohibitive economic power concentrated in only a few large corporations at that time. The Act provides the following: Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several states, or with foreign nations, is declared to be illegal. Every person who shall make any contract or engage in any combination or conspiracy hereby declared to be illegal shall be deemed guilty of a felony…2 It is this statute that has provided a thorn in the side of professional baseball players for over a century. Why is this the case? Because the teams that employ the players are exempt from the provisions of the Sherman Act. 1 Professor of Taxation and Business Law, Monroe College, the Bronx, New York. B.S., 1987, Accounting, Hunter College of the City University of New York; M.S., 1990, Taxation, Long Island University; J.D., 1998 Southern New England School of Law; LL.M., 2005, Touro College Jacob D. -

The 112Th World Series Chicago Cubs Vs. Cleveland Indians Saturday, October 29, 2016 Game 4 - 7:08 P.M

THE 112TH WORLD SERIES CHICAGO CUBS VS. CLEVELAND INDIANS SATURDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2016 GAME 4 - 7:08 P.M. (CT) FIRST PITCH WRIGLEY FIELD, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 2016 WORLD SERIES RESULTS GAME (DATE RESULT WINNING PITCHER LOSING PITCHER SAVE ATTENDANCE Gm. 1 - Tues., Oct. 25th CLE 6, CHI 0 Kluber Lester — 38,091 Gm. 2 - Wed., Oct. 26th CHI 5, CLE 1 Arrieta Bauer — 38,172 Gm. 3 - Fri., Oct. 28th CLE 1, CHI 0 Miller Edwards Allen 41,703 2016 WORLD SERIES SCHEDULE GAME DAY/DATE SITE FIRST PITCH TV/RADIO 4 Saturday, October 29th Wrigley Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio 5 Sunday, October 30th Wrigley Field 8:15 p.m. ET/7:15 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio Monday, October 31st OFF DAY 6* Tuesday, November 1st Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio 7* Wednesday, November 2nd Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio *If Necessary 2016 WORLD SERIES PROBABLE PITCHERS (Regular Season/Postseason) Game 4 at Chicago: John Lackey (11-8, 3.35/0-0, 5.63) vs. Corey Kluber (18-9, 3.14/3-1, 0.74) Game 5 at Chicago: Jon Lester (19-5, 2.44/2-1, 1.69) vs. Trevor Bauer (12-8, 4.26/0-1, 5.00) SERIES AT 2-1 CUBS AT 1-2 This is the 87th time in World Series history that the Fall Classic has • This is the eighth time that the Cubs trail a best-of-seven stood at 2-1 after three games, and it is the 13th time in the last 17 Postseason series, 2-1. -

November 13, 2010 Prices Realized

SCP Auctions Prices Realized - November 13, 2010 Internet Auction www.scpauctions.com | +1 800 350.2273 Lot # Lot Title 1 C.1910 REACH TIN LITHO BASEBALL ADVERTISING DISPLAY SIGN $7,788 2 C.1910-20 ORIGINAL ARTWORK FOR FATIMA CIGARETTES ROUND ADVERTISING SIGN $317 3 1912 WORLD CHAMPION BOSTON RED SOX PHOTOGRAPHIC DISPLAY PIECE $1,050 4 1914 "TUXEDO TOBACCO" ADVERTISING POSTER FEATURING IMAGES OF MATHEWSON, LAJOIE, TINKER AND MCGRAW $288 5 1928 "CHAMPIONS OF AL SMITH" CAMPAIGN POSTER FEATURING BABE RUTH $2,339 6 SET OF (5) LUCKY STRIKE TROLLEY CARD ADVERTISING SIGNS INCLUDING LAZZERI, GROVE, HEILMANN AND THE WANER BROTHERS $5,800 7 EXTREMELY RARE 1928 HARRY HEILMANN LUCKY STRIKE CIGARETTES LARGE ADVERTISING BANNER $18,368 8 1930'S DIZZY DEAN ADVERTISING POSTER FOR "SATURDAY'S DAILY NEWS" $240 9 1930'S DUCKY MEDWICK "GRANGER PIPE TOBACCO" ADVERTISING SIGN $178 10 1930S D&M "OLD RELIABLE" BASEBALL GLOVE ADVERTISEMENTS (3) INCLUDING COLLINS, CRITZ AND FONSECA $1,090 11 1930'S REACH BASEBALL EQUIPMENT DIE-CUT ADVERTISING DISPLAY $425 12 BILL TERRY COUNTERTOP AD DISPLAY FOR TWENTY GRAND CIGARETTES SIGNED "TO BARRY" - EX-HALPER $290 13 1933 GOUDEY SPORT KINGS GUM AND BIG LEAGUE GUM PROMOTIONAL STORE DISPLAY $1,199 14 1933 GOUDEY WINDOW ADVERTISING SIGN WITH BABE RUTH $3,510 15 COMPREHENSIVE 1933 TATTOO ORBIT DISPLAY INCLUDING ORIGINAL ADVERTISING, PIN, WRAPPER AND MORE $1,320 16 C.1934 DIZZY AND DAFFY DEAN BEECH-NUT ADVERTISING POSTER $2,836 17 DIZZY DEAN 1930'S "GRAPE NUTS" DIE-CUT ADVERTISING DISPLAY $1,024 18 PAIR OF 1934 BABE RUTH QUAKER -

Golf Goods Paramount and Whippet Golf Balls And

OSVOtCO TO Sportsmen anZ Athletes Base Ball, Trap Shooting Hunting, Fishing. College Foot Ball, Golf. Laivn Tennis. Cricket, Track Athletics, Vasket Ball, Sorter. Court snnif. Billiards, Bowling, Rifle and Revolver Shooting, Automobtlmg. Yachting. Camping, Rowing, Canoeing, Motor Boating, Swimming, Motor Cycling, Polo, Harness Racing and Kennel. VOL. 67. NO, 21 PHILADELPHIA. JULY 22,1916 PRICE 5 CENTS illp:':":::;:-::>::>: George men are chased from the game, probably suspended, IN SHORT METRE when they have a righteous kick. For instance, it looked like bad judgment on the part of Bill Klem to ANAGER FIELDKR JONES, of the Browns, is chase Zimmerman last Tuesday,-as 7Am had a right M one of those veterans who thinks the game is not porting Hilt to talk and argue with the umpire, as he is captain played as intelligently as it formerly was: He said: A WEEBTLT JOUBNAL DEVOTED TO BABB BALL, TRAP of the Cubs. Tet a lot of fellows have been pulling "I have not seen many of the plays which formerly rough stuff, and just because they are stars have been \vere used by winning major league teams. They seem SHOOTING AND ALL CLEAN SFOBTS. getting away with it. Ty Cobb was fined ^25 and to have been forgotten or relegated by the order of *HB WORLD'S OLDEST AND BEST BASB BALL JODKNAL. suspended three days for pulling a stunt that should things. The hitting nowadays is not as strong as it have banned him for a month, without pay, yet maybe used to be in the old days, when the pitchers were ZOTTNDED APRIL, 1SS3 a captain or manager will be soaked just as much as just as good as they are today, and in many instances Cobb for arguing with the umpire over a decision that better. -

Ba Mss 121 Bl-587.69 – Bl-593.69

Collection Number BA MSS 121 BL-587.69 – BL-593.69 Title Tom Meany Scorebooks Inclusive Dates 1947 – 1963 NY teams Access By appointment during regular hours, email [email protected]. Abstract These scorebooks have scored games from spring training, All-Star games, and World Series games, and a few regular season games. Volume 1 has Jackie Robinson’s first game, April 15, 1947. Biography Tom Meany was recruited to write for the new Brooklyn edition of the New York Journal in 1922. The following year he earned a byline in the Brooklyn Daily Times as he covered the Dodgers. Over the years, Meany's sports writing career saw stops at numerous papers including the New York Telegram (later the World-Telegram), New York Star, Morning Telegraph, as well as magazines such as PM and Collier's. Following his sports writing career, Meany joined the Yankees in 1958. In 1961 he joined the expansion Mets as publicity director and later served as promotions director before his untimely death in 1964 at the age of 60. He received the Spink Award in 1975. Source: www.baseballhall.org Content List Volume 1 BL-587.69 1947 - Spring training, season games April 15, Jackie Robinson’s first game World Series - Dodgers v. Yankees 1948 - Spring training Volume 2 BL-588.69 1948 – Season games World Series, Indians vs. Braves 1962 - World Series, Giants vs. Yankees Volume 3 BL-589.69 1949 -Spring training, season games 1950 - May, Jul 11 All-Star game World Series, Yankees vs. Phillies 1951 - Playoff games, Dodgers vs. Giants World Series, Giants vs.