A Look at the 2014 Isla Vista Killings∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intersectionality: T E Fourth Wave Feminist Twitter Community

#Intersectionality: T e Fourth Wave Feminist Twitter Community Intersectionality, is the marrow within the bones of fem- Tegan Zimmerman (PhD, Comparative Literature, inism. Without it, feminism will fracture even further – University of Alberta) is an Assistant Professor of En- Roxane Gay (2013) glish/Creative Writing and Women’s Studies at Stephens College in Columbia, Missouri. A recent Visiting Fel- This article analyzes the term “intersectional- low in the Centre for Contemporary Women’s Writing ity” as defined by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw (1989, and the Institute of Modern Languages Research at the 1991) in relation to the digital turn and, in doing so, University of London, Zimmerman specializes in con- considers how this concept is being employed by fourth temporary women’s historical fiction and contempo- wave feminists on Twitter. Presently, little scholarship rary gender theory. Her book Matria Redux: Caribbean has been devoted to fourth wave feminism and its en- Women’s Historical Fiction, forthcoming from North- gagement with intersectionality; however, some notable western University Press, examines the concepts of ma- critics include Kira Cochrane, Michelle Goldberg, Mik- ternal history and maternal genealogy. ki Kendall, Ealasaid Munro, Lola Okolosie, and Roop- ika Risam.1 Intersectionality, with its consideration of Abstract class, race, age, ability, sexuality, and gender as inter- This article analyzes the term “intersectionality” as de- secting loci of discriminations or privileges, is now the fined by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in relation to the overriding principle among today’s feminists, manifest digital turn: it argues that intersectionality is the dom- by theorizing tweets and hashtags on Twitter. Because inant framework being employed by fourth wave fem- fourth wave feminism, more so than previous feminist inists and that is most apparent on social media, espe- movements, focuses on and takes up online technolo- cially on Twitter. -

Download Download

DOI: 10.4119/ijcv-3805 IJCV: Vol. 14(2)/2020 Connecting Structures: Resistance, Heroic Masculinity and Anti-Feminism as Bridging Narratives within Group Radicalization David Meieringi [email protected] Aziz Dzirii [email protected] Naika Foroutani [email protected] i Berlin Institute for Integration and Migration Research (BIM) at the Humboldt University Berlin Vol. 14(2)/2020 The IJCV provides a forum for scientific exchange and public dissemination of up-to-date scien- tific knowledge on conflict and violence. The IJCV is independent, peer reviewed, open access, and included in the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) as well as other rele- vant databases (e.g., SCOPUS, EBSCO, ProQuest, DNB). The topics on which we concentrate—conflict and violence—have always been central to various disciplines. Consequently, the journal encompasses contributions from a wide range of disciplines, including criminology, economics, education, ethnology, his- tory, political science, psychology, social anthropology, sociology, the study of reli- gions, and urban studies. All articles are gathered in yearly volumes, identified by a DOI with article-wise pagi- nation. For more information please visit www.ijcv.or g Suggested Citation: APA: Meiering, D., Dziri, A., & Foroutan, N. (2020). Connecting structures: Resistance, heroic masculinity and anti-feminism as bridging narratives within group radicaliza- tion. International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 14(2), 1-19. doi: 10.4119/ijcv-3805 Harvard: Meiering, David, Dziri, Aziz, Foroutan, Naika. 2020. Connecting Structures: Resistance, Heroic Masculinity and Anti-Feminism as Bridging Narratives within Group Radicalization. International Journal of Conflict and Violence 14(2): 1-19. doi: 10.4119/ijcv-3805 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution—NoDerivatives License. -

Resistance, Heroic Masculinity and Anti-Feminism As Bridging Narratives Within Group Radicalization

�������� ������������� � � ��������� ����������� ��������������������������������� �!������"����#����$���%� &����'�(����(����)��%�����*����������+��,���-���.� ��%���#�/����� ����%�"�������� %���%�(�������0,��1��#���%� &/�/��/���� %/����/20,��1��#���%� *��3��'�������� 4�������0,��1��#���%� ��)��#�������������4�����������������%�"����������������,�5)�"6�����,��!�(1�#%��7��������$�)��#�� 8�#��� 596�9�9� :,���;�8 .����%�����4���(�4����������4����2�,�������%�.�1#���%����(���������4��.����%���������� ��4���3��+#�%���������4#������%����#������:,���;�8������%�.��%��� �.���������+�% ��.�� ������ ���%����#�%�%�����,�������#���������������������%�2�5����6����+�##������,�����#�� �����%���1�����5���� ����<7� �=)��� �<��>��� ��*)6�� :,����.�������+,��,�+�������������?���4#������%����#����?,�����#+�$��1����������# �����������%����.#�����������@����#$ ��,��������#�����(.������������1�������4��(�� +�%���������4�%����.#���� ����#�%�������(���#��$ ������(��� ��%������� ���,��#��$ �,��� ���$ �.�#�����#�������� �.�$�,�#��$ ������#����,��.�#��$ ������#��$ ��,�����%$��4���#�� ����� ���%���1������%����� &##������#����������,���%����$���#$���#�(�� ��%����4��%�1$�������+��,������#��+����.���� ������� '���(������4��(������.#�������������+++����������� ��������%���������� &<&��"������� ��� ��/��� �&� �A�'������� �*��59�9�6����������������������������������� ,������(����#����$���%������4�(����(����1��%����������������+��,�������.���%���#�/�� ������������������ ������� �������� ����������� ��������596��������%������� ������������� !�����%� �"������� �����% ��/��� -

The Incel Lexicon: Deciphering the Emergent Cryptolect of a Global Misogynistic Community

The incel lexicon: Deciphering the emergent cryptolect of a global misogynistic community Kelly Gothard,1 David Rushing Dewhurst,2 Joshua R. Minot,1 Jane Lydia Adams,1 Christopher M. Danforth,1, 3, 4 and Peter Sheridan Dodds1, 3, 4 1Computational Story Lab, Vermont Complex Systems Center, MassMutual Center of Excellence for Complex Systems and Data Science, Vermont Advanced Computing Core, The University of Vermont, Burlington, VT 05401. 2Charles River Analytics, 625 Mount Auburn Street, Cambridge, MA 02138. 3Department of Mathematics & Statistics, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT 05401. 4Department of Computer Science, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT 05401. (Dated: May 26, 2021) Evolving out of a gender-neutral framing of an involuntary celibate identity, the concept of `incels' has come to refer to an online community of men who bear antipathy towards themselves, women, and society-at-large for their perceived inability to find and maintain sexual relationships. By exploring incel language use on Reddit, a global online message board, we contextualize the incel community's online expressions of misogyny and real-world acts of violence perpetrated against women. After assembling around three million comments from incel-themed Reddit channels, we analyze the temporal dynamics of a data driven rank ordering of the glossary of phrases belonging to an emergent incel lexicon. Our study reveals the generation and normalization of an extensive coded misogynist vocabulary in service of the group's identity. I. INTRODUCTION with the incel community, such as the Tallahassee yoga studio shooting, during which Scott Beierle Incels are self-identified members of a global, shot and killed two women shortly after referencing online subculture whose members subscribe to Elliot Rodger in videos online [5]. -

Om Mäns Pro- Och Antifeministiska Engagemang

Om mäns pro- och antifeministiska engagemang Jonas Mollwing Pedagogiska institutionen Umeå centrum för genusstudier, Genusforskarskolan Umeå 2021 Detta verk är skyddat av svensk upphovsrätt (Lag 1960:729) Avhandling för filosofie doktorsexamen ISBN: 978-91-7855-477-5 (print) ISBN: 978-91-7855-478-2 (pdf) ISSN: 0281-6768 Akademiska avhandlingar vid Pedagogiska institutionen, Umeå universitet; nr 127 Omslag: Gabriella Dekombis, Umeå universitet Elektronisk version tillgänglig på: http://umu.diva-portal.org/ Tryck: Cityprint i Norr AB Umeå, Sverige 2021 Till Njord, Egil, Freja och Sol Innehållsförteckning Introduktion ...................................................................................... 1 Inledning ........................................................................................................................... 1 Profeminism och antifeminism ................................................................................ 4 Syfte och frågeställningar ......................................................................................... 7 Avhandlingens disposition ........................................................................................ 7 Vetenskapligt förhållningssätt ........................................................................................ 9 Vetenskapsfilosofiska antaganden........................................................................... 9 Kunskapens dimensioner .................................................................................... 9 Verklighetens djup ............................................................................................. -

Defections by GOP Kill Health Bill For

CYAN MAGENTA YELLOW BLACK » TODAY’S ISSUE U DAILY BRIEFING, A2 • TRIBUTES, A5 • WORLD & BUSINESS, B5 • CLASSIFIEDS, B6 • PUZZLES & TV, C3 CLASS B BASEBALL CHAMPION SCRAPPERS ROLL COMING TO COVELLI 50% Baird bests Astro in Game 5 7-run 7th bedevils Batavia Stevie Nicks show set for Sept. 15 OFF SPORTS | B1 SPORTS | B1 VALLEY LIFE | C1 vouchers. DETAILS, A2 FOR DAILY & BREAKING NEWS LOCALLY OWNED SINCE 1869 TUESDAY, JULY 18, 2017 U 75¢ Lordstown police: Pot smuggling via Fusion has occurred before Law enforcement Marijuana bales were found on popular Ford car at rail yard in 2015 seized marijuana in the trunks of Ford By ED RUNYAN ment on Monday Detective Chris Bordonaro of Fusions at dealerships [email protected] provided the de- the Lordstown police said the rail in Portage, Stark LORDSTOWN tails after Jeff Orr, yard notifi ed Lordstown offi cers and Columbiana Last week was not the fi rst time former Trumbull after finding 50 to 100 pounds counties, as well as that marijuana made its way from Ashtabula Group of marijuana attached to the one in Pennsylvania. VINDICATOR The rail car carrying Mexico to the United States inside Law Enforcement EXCLUSIVE Fusion. the Fusions had come the spare-tire compartments of Task Force com- It appeared tape was used to from Hermosillo, Ford Fusions via the CSX rail yard mander, revealed secure the marijuana, and rem- Mexico, and had sat in Lordstown. the case to The Vindicator. nants of the tape were found on idle in Chicago 18 An Aug. 7, 2015, incident at the In that case, bales of marijuana 11 other vehicles, suggesting the hours before coming same rail yard, which is off state were found attached to the un- drugs had been off-loaded from to Lordstown. -

To What Extent Incels' Misogynistic and Violent Attitudes Towards

To what extent Incels’ misogynistic and violent attitudes towards women are driven by their unsatisfied mating needs and entitlement to sex? Bachelor Thesis in Psychology Faculty of Behavioural, Management and Social Sciences Department of Psychology Author: Sara Konutgan (s1839454) Supervisor: Dr. Pelin Gül & Noortje Kloos, MSc To what extent are Incels’ misogynistic and violent attitudes towards women driven by their unsatisfied mating needs and entitlement to sex? Sara Konutgan University of Twente Abstract The purpose of this research is to investigate which psychological factors drive Incels to have violent and misogynistic attitudes towards women. This paper focuses on the investigation of two psychological factors: entitlement and frustrated mating needs. A cross-sectional survey design was used to gather data through an online survey. The sample involved 139 participants of which 28 participants define themselves as Incels. The results of the multiple regression analysis indicated that participants who have higher feelings of entitlement to sex and higher struggles with romantic and sexual relationships show a higher level of misogyny and violent attitudes towards women. This study contributes to the understanding of the psychological factors that drive misogynistic ideologies that exist among Incels as well as in society. Keywords: Incels, Entitlement, Misogyny, Sexual Frustration, Romantic Frustration, Frustrated Mating Needs 1 Introduction The term “Incel” is the short form for being an involuntary celibate which can be defined as being unable to find a partner for sexual or romantic relationships even though it is desired (Young, 2019). Some Incels are sharing their attitudes and opinions in online forums. Although not all members of Incel communities have misogynistic or violent attitudes towards women, some members are sharing misogyny (Ging, 2017). -

Exhibit SS-LLL to the Declaration of Anna M

Case 3:17-cv-01017-BEN-JLB Document 6-7 Filed 05/26/17 PageID.644 Page 1 of 105 1 C.D. Michel – SBN 144258 Sean A. Brady – SBN 262007 2 Anna M. Barvir – SBN 268728 Matthew D. Cubeiro – SBN 291519 3 MICHEL & ASSOCIATES, P.C. 180 E. Ocean Boulevard, Suite 200 4 Long Beach, CA 90802 Telephone: (562) 216-4444 5 Facsimile: (562) 216-4445 Email: [email protected] 6 Attorneys for Plaintiffs 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 VIRGINIA DUNCAN, RICHARD Case No: 17-cv-1017-BEN-JLB LEWIS, PATRICK LOVETTE, DAVID 11 MARGUGLIO, CHRISTOPHER EXHIBITS SS-LLL TO THE WADDELL, CALIFORNIA RIFLE & DECLARATION OF ANNA M. 12 PISTOL ASSOCIATION, BARVIR IN SUPPORT OF INCORPORATED, a California PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR 13 corporation, PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION 14 Plaintiffs, 15 v. 16 XAVIER BECERRA, in his official capacity as Attorney General of the State 17 of California; and DOES 1-10, 18 Defendants. 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 1 EXHIBITS SS-LLL 17-cv-1017-BEN-JLB Case 3:17-cv-01017-BEN-JLB Document 6-7 Filed 05/26/17 PageID.645 Page 2 of 105 1 EXHIBITS 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Exhibit Letter Description Page Numbers 4 E Gun Digest 2013 (Jerry Lee ed., 67th ed. 2012) 000028-118 5 F Website pages for Glock “Safe Action” Gen4 Pistols, 000119-157 6 Glock; M&P®9 M2.0™, Smith & Wesson; CZ 75 B, CZ- 7 USA; Ruger® SR9®, Ruger; P320 Nitron Full-Size, Sig 8 Sauer 9 G Pages 73-97 from The Complete Book of Autopistols: 2013 000158-183 10 Buyer’s Guide (2013) 11 H David B. -

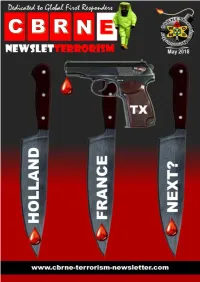

MAY 2018 Part C.Pdf

Page | 1 CBRNE-TERRORISM NEWSLETTER – May 2018 www.cbrne-terrorism-newsletter.com Page | 2 CBRNE-TERRORISM NEWSLETTER – May 2018 www.cbrne-terrorism-newsletter.com Page | 3 CBRNE-TERRORISM NEWSLETTER – May 2018 Weaponizing Artificial Intelligence: The Scary Prospect Of AI- Enabled Terrorism By Bernard Marr Source: https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2018/04/23/weaponizing-artificial-intelligence-the- scary-prospect-of-ai-enabled-terrorism/#7c68133877b6 There has been much speculation about the power and dangers of artificial intelligence (AI), but it’s been primarily focused on what AI will do to our jobs in the very near future. Now, there’s discussion among tech leaders, governments and journalists about how artificial intelligence is making lethal autonomous weapons systems possible and what could transpire if this technology falls into the hands of a rogue state or terrorist organization. Debates on the moral and legal implications of autonomous weapons have begun and there are no easy answers. Autonomous weapons already developed The United Nations recently discussed the use of autonomous weapons and the possibility to institute an international ban on “killer robots.” This debate comes on the heels of more than 100 leaders from the artificial intelligence community, including Tesla’s Elon Musk and Alphabet’s Mustafa Suleyman, warning that these weapons could lead to a “third revolution in warfare.” Although artificial intelligence has enabled improvements and efficiencies in many sectors of our economy from entertainment to transportation to healthcare, when it comes to weaponized machines being able to function without intervention from humans, a lot of questions are raised. There are already a number of weapons systems with varying levels of human involvement that are actively being tested today. -

Narrative Warfare: the 'Careless' Reinterpretation of Literary Canon

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE This is the accepted manuscript of the article, which has been published in Narrativeprovided by Trepo Inquiry - Institutional. 2019,Repository of Tampere University 29(2), 313-332. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.19019.nur Narrative Warfare: The ‘Careless’ Reinterpretation of Literary Canon in Online Antifeminism Matias Nurminen, Tampere University This article studies the use of literature and narrative strategies of online antifeminist movements. These movements classified under the umbrella term the manosphere, wage ideological narrative warfare to endorse a misogynistic worldview. The case at hand concentrates on the radical faction of neomasculinity and its attempts to reinterpret the Western canon of literature. I propose that neomasculine readings of novels such as Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita are careless interpretations that ground themselves on specific traits of the texts while ignoring others. These readings attempt to evoke a sense of recognition in the community that believes in an alleged feminist conspiracy against men. Careless interpretations borrow from post-truth rhetoric and the feminist literary theory tradition of reading against the grain. When confronted over their controversial views, neomasculine figures renarrativize readings to benefit the promotion of neomasculine perspectives. This strategic use of literature is part of the narrative warfare discussed in detail. Keywords: manosphere, resistant reading, post-truth, instrumental narratives, antifeminism, literary canon 1 Introduction This article analyses how online antifeminist movements, often classified under the umbrella term the manosphere, wage ideological narrative warfare to endorse a misogynistic worldview. The case at hand concentrates on neomasculinity, a particularly radical faction that has also been studied in classicist Donna Zuckerberg’s recent book Not All Dead White Men: Classics and Misogyny in the Digital Age (2018). -

Open Hatef Azeta Dissertation.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Donald P. Bellisario College of Communications ALTERNATIVE SPACES OF ENGAGEMENT: CONSTRUCTING MEANING THROUGH TRADITIONAL AND SOCIAL MEDIA AMONG ROMA IN THE CZECH REPUBLIC A Dissertation in Mass Communications by Azeta Hatef © 2019 Azeta Hatef Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2019 The dissertation of Azeta Hatef was reviewed and approved* by the following: Matthew P. McAllister Professor of Communications Chair of Graduate Programs Chair of Committee Dissertation Adviser Michelle Rodino-Colocino Associate Professor of Communications Matthew Jordan Associate Professor of Communications Yael Warshel Assistant Professor of Communications; Research Associate, Rock Ethics Institute *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii Abstract This dissertation examines the use of televisual media forms and social media outlets by Roma activists in the Czech Republic as these activists search for ways to ameliorate discrimination, exclusion and the challenges of identity and community building among the Roma within Czech society. Roma marginalization manifests in a myriad of ways including explicitly through practices such as discriminatory housing and educational segregation. There are also the implicit methods of exclusion including the silencing of voices and experiences. Media are one of the sites that have excluded Roma and continue to present Roma in limited and stereotypical ways with harmful implications. This dissertation explores the specific efforts and outcomes of those engaged in challenging and changing this situation, which is critical for ascertaining a broader understanding of the dynamics and formulating new strategies for change. In particular, this study sets out to understand the ways in which activists attempt to engage communities using media—televisual, online and social media—as sites for identity negotiation and community development, that may in turn contribute to a sense of belonging to help combat unjust systems. -

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper Mckinley Rd. Mckinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date: August 22, 2016 1 ALLOWED MARKS PUBLISHED FOR OPPOSITION .................................................................................................... 2 1.1 ALLOWED NATIONAL MARKS ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date: August 22, 2016 1 ALLOWED MARKS PUBLISHED FOR OPPOSITION 1.1 Allowed national marks Application No. Filing Date Mark Applicant Nice class(es) Number 7 1 4/2012/00503191 December HEYS GROUP IP HOLDING LP [CA] 18 2012 7 2 4/2012/00503192 December HEYS GROUP IP HOLDING LP [CA] 18 2012 8 January 3 4/2013/00000196 DREAMWELL, LTD. [US] 20 2013 18 July CRISTALINO JAUME PABLO GARCIA-MORERA 4 4/2013/00008524 33 2013 SERRA [PH] MULTISPORT 22 July HINGE INQUIRER 5 4/2013/00008673 PHILIPPINES. SWIM 16 2013 PUBLICATIONS, INC. [PH] BIKE & RUN 29 August 6 4/2013/00010298 EOCEF EON PHARMATEK, INC. [PH] 5 2013 26 SHENZHEN CHUANGWEI- 7 4/2014/00002483 February MANNA RGB ELECTRONICS CO., 9 2014 LTD [CN] 29 April EUROHEALTHCARE 8 4/2014/00005142 CLAVMEX 5 2014 EXPONENTS, INC. [PH] 16 May DERMASIA SKIN CATHERINE ESTRADA 9 4/2014/00006191 44 2014 CARE CENTER PANGAN [PH] CENTER OF EXCELLENCE 2 June IN DRUG RESEARCH, 10 4/2014/00006933 CEDRES 42 2014 EVALUATION AND STUDIES, INC. [PH] 10 June 11 4/2014/00007299 JINMA JINYONG CAI [PH] 5 and9 2014 10 June EMERALD EIGHTY SAN MIGUEL 12 4/2014/00007344 36 and37 2014 EIGHT CORPORATION [PH] 25 June EUROHEALTHCARE 13 4/2014/00008050 BEAR-VITES 5 2014 EXPONENTS, INC.