Urban Metabolism of Intermediate Cities: the Material Flow Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards a Dynamic Assessment of Raw Materials Criticality: Linking Agent-Based Demand--With Material Flow Supply Modelling Approaches

This is a repository copy of Towards a dynamic assessment of raw materials criticality: linking agent-based demand--with material flow supply modelling approaches.. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/80022/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Knoeri, C, Wäger, PA, Stamp, A et al. (2 more authors) (2013) Towards a dynamic assessment of raw materials criticality: linking agent-based demand--with material flow supply modelling approaches. Science of the Total Environment, 461-46. 808 - 812. ISSN 0048-9697 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.02.001 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Towards a dynamic assessment of raw materials criticality: Linking agent-based demand - with material flow supply modelling approaches Christof Knoeri1, Patrick A. -

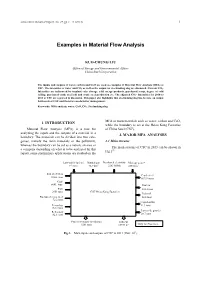

Examples in Material Flow Analysis

China Steel Technical Report, No. 27, pp.1-5, (2014) Kuo-Chung Liu 1 Examples in Material Flow Analysis KUO-CHUNG LIU Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs China Steel Corporation The inputs and outputs of water, carbon and CaO are used as examples of Material Flow Analysis (MFA) at CSC. The intensities of water and CO2 as well as the output for steelmaking slag are discussed. Current CO2- Intensities are influenced by in-plant coke storage, sold energy products, purchased scrap, degree of cold rolling, purchased crude steel/roll and crude steel production etc. The adjusted CO2- Intensities for 2010 to 2013 at CSC are reported in discussion. This paper also highlights that steelmaking slag has become an output bottleneck at CSC and therefore needs better management. Keywords: MFA analysis, water, CaO, CO2, Steelmaking slag MFA of main materials such as water, carbon and CaO, 1. INTRODUCTION while the boundary is set at the Hsiao Kang Factories Material Flow Analysis (MFA) is a tool for of China Steel (CSC). analyzing the inputs and the outputs of a material in a 2. MAJOR MFA ANALYSES boundary. The materials can be divided into two cate- gories, namely the main materials or the pollutants, 2.1 Main streams whereas the boundary can be set as a nation, an area or The main streams of CSC in 2013 can be shown in a company depending on what is to be analyzed. In this Fig.1(1). report, some preliminary applications are studied on the Low-sulfer fuel oil Natural gas Purchased electricity Makeup water* 9.3 tons 76.9 km3 2283 MWh 45554 m3 Iron ore/Pellets Crude steel 13066 tons 8693.6 tons Coal 6801 tons Coal tar Flux 205.2 tons 2951 tons CSC Hsiao Kang Factories Light oil Purchased scrap steel 54.8 tons 72.2 tons Liquid sulfur Ferroalloy 11.3 tons 132.1 tons Iron oxide powder Refractory 82.6 tons 28.7 tons Process residues (wet basis) Effluent 5281 tons 14953 m3 Only for Processes. -

Urban Metabolism: a Review of Recent Literature on the Subject

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Revistes Catalanes amb Accés Obert Documents d’Anàlisi Geogràfica 2014, vol. 60/3 551-571 Urban Metabolism: A review of recent literature on the subject Marta Dinarès Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB). Departament de Geografia Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals (ICTA) Grup d’investigació INTERFASE en recursos, territoris i paisatges marins i costaners [email protected] Received: November 2013 Accepted: April 2014 Abstract Urban areas are the primary habitat for a majority of the global population. The deve- lopment of cities not only entails a fundamental change in human settlement patterns but also a dramatic transformation of the physical environment. Thus, urban areas and their development are at the centre of all discussions on sustainability and/or sustainable development. This review essay introduces the notion of Urban Metabolism (UM), a term that provides a conceptual framework to study how a city functions, and hence, a way to address the sustainability issue of a city. Due to the significance and scope of the subject, the notion of UM is interpreted and thus approached differently across diverse disciplines from both the natural and social science fields. In order to comprehend the commonalities and controversies between them, the present review also briefly introduces the historical roots of the term. This review reveals the increasing significance of a rich and rapidly evolving field of research on the metabolism of urban areas. Keywords: urban metabolism; city; sustainability; sustainable development; environment; fields of discipline. Resum. Metabolisme urbà: una revisió de la literatura recent sobre el tema Les àrees urbanes són el principal hàbitat de la majoria de la població mundial. -

Analyzing Small and Medium-Sized Towns in the Light of Their Constraints and Opportunities - the Case of Nevers (Burgundy - France)

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Navarre, Françoise; Delpirou, Aurelien Conference Paper Analyzing Small and Medium-Sized towns in the light of their constraints and opportunities - the case of Nevers (Burgundy - France) 54th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Regional development & globalisation: Best practices", 26-29 August 2014, St. Petersburg, Russia Provided in Cooperation with: European Regional Science Association (ERSA) Suggested Citation: Navarre, Françoise; Delpirou, Aurelien (2014) : Analyzing Small and Medium-Sized towns in the light of their constraints and opportunities - the case of Nevers (Burgundy - France), 54th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Regional development & globalisation: Best practices", 26-29 August 2014, St. Petersburg, Russia, European Regional Science Association (ERSA), Louvain-la-Neuve This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/124545 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Recycling the City: the Impact of Urban Change on the Informal Waste-Recovery Trade in Hanoi, Vietnam

RECYCLING THE CITY: THE IMPACT OF URBAN CHANGE ON THE INFORMAL WASTE-RECOVERY TRADE IN HANOI, VIETNAM By Carrie L. Mitchell A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Geography University of Toronto Copyright by Carrie L. Mitchell 2008 ii Recycling the City: The Impact of Urban Change on the Informal Waste-Recovery Trade in Hanoi, Vietnam Doctor of Philosophy, 2008 Carrie L. Mitchell Graduate Department of Geography University of Toronto Abstract This three-paper dissertation explores how broader (and often unchallenged) changes to political economy at multiple geographic and economic scales impact long-standing ‘informal’ practices of waste recovery and recycling in Hanoi, Vietnam. This research is based on a survey of 575 informal waste collectors and 264 waste intermediaries as well as 73 in-depth interviews. Paper I engages in a critique of methodological disclosure in current academic writings on informal waste-recovery activities and discusses the methodological difficulties of researching informal populations. My aim in this paper is to highlight that the lack of methodological disclosure in waste-recovery literature is problematic because it compromises the academic rigour of this field and impedes the reliability of researchers’ policy recommendations as well as to initiate a dialogue with the aim of improving methodological rigour in waste-recovery literature. Paper II examines urbanization processes in contemporary Vietnam and how these changing spaces accommodate labour, and in turn support livelihoods. I argue that Vietnam’s globalizing economy and urban transition have been a catalyst for the growth of the informal waste collector population in Hanoi, as well as a partial player in the gendering of the industry. -

Economy-Wide Material Flow Accounts Handbook – 2018 Edition

Economy-wide material flow accounts HANDBOOK 2018 edition Economy-wide material flow accounts flow material Economy-wide 2 018 edition 018 MANUALS AND GUIDELINES Economy-wide material flow accounts HANDBOOK 2018 edition Manuscript completed in June 2018 Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use that might be made of the following information. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2018 © European Union, 2018 Reproduction is authorized for non-commercial purposes only, provided the source is acknowledged. The reuse policy of European Commission documents is regulated by Decision 2011/833/EU (OJ L 330, 14.12.2011, p. 39). Copyright for the photographs: Cover © Vladimir Wrangel/Shutterstock For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the EU copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. For more information, please consult: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/about/policies/copyright Theme: Environment and energy Collection: Manuals and guidelines The opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) only and should not be considered as representative of the official position of the European Commission Neither the European Union institutions and bodies nor any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained herein ISBN 978-92-79-88337-8 ISSN 2315-0815 doi: 10.2785/158567 Cat. No: KS-GQ-18-006-EN-N Preface Preface Economy-wide material flow accounts (EW-MFA) are a statistical accounting framework describing the physical interaction of the economy with the natural environment and the rest of the world economy in terms of flows of materials. -

An Overview of Istat's Environmental Accounting in the Light of Eu

An Overview of Istat’s Environmental Accounting in the Light of Eu Methodological Achievements Una visione d’insieme della contabilità ambientale dell’Istat alla luce di avanzamenti metodologici a livello europeo Cesare Costantino Istat, Direzione Centrale Contabilità Nazionale, Via Ravà 150, Roma, [email protected] Riassunto: La contabilità ambientale è una disciplina sviluppata nell’ambito degli organismi internazionali in relazione alle esigenze dello sviluppo sostenibile; essa trae origine dalla contabilità nazionale e si occupa in maniera sistematica e comprensiva del rapporto economia-ambiente. Una pluralità di conti, standardizzati in ambito europeo, consente di focalizzare aspetti specifici dell’interazione tra economia e ambiente, permettendo di confrontare i fatti economici e i fatti ambientali correlati attraverso un sistema coerente di definizioni e classificazioni. La produzione dell’Istat risponde alle esigenze conoscitive del paese e degli organismi internazionali, in particolare comunitari; in linea con la strategia europea per la contabilità ambientale, essa è a regime per quanto concerne la MFA, la NAMEA e l’EPEA, i conti a più elevata priorità. Keywords: economy-environment interaction, SEEA, DPSIR, MFA, NAMEA, EPEA. 1. Sustainable development strategy and environmental accounting Sustainable development calls for a variety of changes in the functioning of society. Innovations are needed involving different aspects such as e.g. production and consumption patterns and mechanisms for determining social choices. New statistical information is needed as well, to support decisions by institutions, enterprises and individuals, being clear that it is essential to integrate the institutional, economic, social and environmental dimensions of sustainable development. In Italy the importance of integrating economic and environmental aspects has been emphasized in the political agenda since the ’nineties. -

Co-Creating Sustainable Urban Metabolism Towards Healthier Cities Isabel Fróes1* and Malene Køster Lasthein2

Fróes and Lasthein Urban Transformations (2020) 2:5 Urban Transformations https://doi.org/10.1186/s42854-020-00009-7 RESEARCH Open Access Co-creating sustainable urban metabolism towards healthier cities Isabel Fróes1* and Malene Køster Lasthein2 * Correspondence: [email protected] 1Department of Management Abstract Society and Communication, Copenhagen Business School, In this article, we initially present and discuss the existing concepts covering Dalgas Have 15, 2000 Frederiksberg, sustainable and healthy cities, and urban metabolism infrastructure. The urban Denmark metabolism infrastructure distributes a wide range of key resources to citizens Full list of author information is available at the end of the article through various modes of transportation. Although the technical infrastructure and people in cities tend to be perceived as separate systems, they need to be acknowledged as co-dependent. Thus, co-creating urban metabolism and its infrastructure should be an integral part of developing a healthy city. We use mobility and transportation examples from the Cities-4-People project as a case to discuss the role of citizens and local stakeholders in co-creating solutions to improve their cities’ mobility through the urban metabolism and sustainability lens. Furthermore, we discuss the project process outcomes, leading to a set of guidelines towards achieving healthier cities. Keywords: Urban metabolism, Healthy city, Urban infrastructure, Co-creation, Sustainable city, Urban prototyping Science highlights section To develop healthier cities requires an understanding of the ever changing citizens’ needs and how their choices impact the local urban metabolism. Co-production and co-creation of urban solutions with local citizens and other stakeholders contribute to a wider awareness of the city as an inter-dependent me- tabolism as a possible approach to achieve the WHO healthy city parameters. -

The Study of Urban Metabolism and Its Applications to Urban Planning and Design” by Kennedy Et Al

Environmental Pollution 167 (2012) 184–185 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Environmental Pollution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/envpol Letter to the Editor Comment on “The study of urban metabolism and its applications to urban planning and design” by Kennedy et al. (2011) Dear Editor, and wastes for an urban region metabolism (Barles, 2010; Kennedy et al., 2011). In a recent article published in your journal “The Study of Third, we speculate the discrepancies above described stem Urban Metabolism and its Applications to Urban Planning and from the differences between the two disciplines in their intellec- Design ”(Kennedy et al., 2011), the authors stated that the concept tual foci. Urban sociologists focus on the human condition and of urban metabolism was conceived by Wolman in 1965, and are more interested in how and where urban settlements arose observed that its applications have been found primarily in urban and the factors that influenced their internal arrangement ecology (or industrial ecology in their terms). These raise several (McDonald and Patterson, 2007). Burgess, for example, subse- questions: Did Wolman actually coin the term? Has the term quently developed a concentric zone model to explain urban social been used in other disciplines than urban ecology? If so, what structures (Park et al., 1925). On the other hand, urban ecologists or are the major differences, if any, across disciplinary boundaries? in this case, industrial ecologists as Kennedy et al. (2011) named in And why? In this letter, we intend to briefly respond to these their article, focus primarily on the cycling of matter and energy questions. -

Transformations)

TRANSFORMACJE (TRANSFORMATIONS) Transformacje (Transformations) is an interdisciplinary refereed, reviewed journal, published since 1992. The journal is devoted to i.a.: civilizational and cultural transformations, information (knowledge) societies, global problematique, sustainable development, political philosophy and values, future studies. The journal's quasi-paradigm is TRANSFORMATION - as a present stage and form of development of technology, society, culture, civilization, values, mindsets etc. Impacts and potentialities of change and transition need new methodological tools, new visions and innovation for theoretical and practical capacity-building. The journal aims to promote inter-, multi- and transdisci- plinary approach, future orientation and strategic and global thinking. Transformacje (Transformations) are internationally available – since 2012 we have a licence agrement with the global database: EBSCO Publishing (Ipswich, MA, USA) We are listed by INDEX COPERNICUS since 2013 I TRANSFORMACJE(TRANSFORMATIONS) 3-4 (78-79) 2013 ISSN 1230-0292 Reviewed journal Published twice a year (double issues) in Polish and English (separate papers) Editorial Staff: Prof. Lech W. ZACHER, Center of Impact Assessment Studies and Forecasting, Kozminski University, Warsaw, Poland ([email protected]) – Editor-in-Chief Prof. Dora MARINOVA, Sustainability Policy Institute, Curtin University, Perth, Australia ([email protected]) – Deputy Editor-in-Chief Prof. Tadeusz MICZKA, Institute of Cultural and Interdisciplinary Studies, University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland ([email protected]) – Deputy Editor-in-Chief Dr Małgorzata SKÓRZEWSKA-AMBERG, School of Law, Kozminski University, Warsaw, Poland ([email protected]) – Coordinator Dr Alina BETLEJ, Institute of Sociology, John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, Poland Dr Mirosław GEISE, Institute of Political Sciences, Kazimierz Wielki University, Bydgoszcz, Poland (also statistical editor) Prof. -

Sustainable Consumption and Production - Development of an Evidence Base

Sustainable Consumption and Production - Development of an Evidence Base. Project Ref.: SCP001 Resource Flows Sustainable Consumption and Production - Development of an Evidence Base Appendix to Final Project Report Appendix SCP001 1/196 Projec Ref.: SCP001 Resource Flows May 2006 Appendix SCP001 2/196 Contents I Review of Resource Flow Studies (Section 4) 6 I.1 Specific assessment requirements 6 I.1.1 General Methodological Procedure 6 I.1.2 Assessment Criteria 7 I.1.3 The Scorecard System 12 I.2 Characteristics of General MFA Methodologies 15 I.3 Detailed Assessment Results 19 I.3.1 Economy-wide Material Flow Analysis 19 I.3.2 Bulk Material or Material System Analysis – The Biffaward Series 31 I.3.3 Analysis of Material Flows by Sector: NAMEAs, Generalised Input-Output Models, and Physical Input-Output Analysis 35 I.3.4 Life Cycle Inventories 47 I.3.5 Substance Flow Analysis 54 I.3.6 Hybrid Methodologies 61 I.4 Environmental Impact Assessments 66 I.5 Policy Analysis 73 I.6 Discussion of Study by Van der Voet et al. (2005) 77 II Review of Biffaward Studies (Section 5) 79 II.1 Tables: Detailed assessment criteria, policy agendas, list of Biffaward studies 79 II.2 Assessment notes made for each study 87 III Development of an Indicator for Emissions and Impacts associated with the Consumption of Imported Goods and Services (Section 6) 152 III.1 Specific assessment requirements 152 III.2 Review of existing approaches described in the literature 155 III.2.1 Studies not involving input-output calculations 155 III.2.2 Studies involving input-output -

Indicators Based on Material Flow Analysis/Accounting (MFA) and Resource Productivity

Indicators based on Material Flow Analysis/Accounting (MFA) and Resource Productivity Yasuhiko Hotta Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES), Japan Chettiyappan Visvanathan Asian Institute of Technology 01 Outline of indicators The global consumption of natural resources is soaring, especially in rapidly industrialising economies. This increasing demand is depleting the natural resource stocks and is also a major driver for other environmental problems, including climate change and the loss of biodiversity. Efficient resource use has become an issue for policy makers in their efforts to realise sustainable resource management. Keeping an account of the resource inputs, extraction and consumption, as well as analysing the outputs (as waste) is a fundamental need when planning resource efficiency and conservation. Material Flow Analysis/Accounting (MFA) is an analytical method of quantifying flows and stocks of materials or substances in a well-defined system. MFA can be applied at several levels, such as product, regional and national economy level. The accounting may be directed at selected substances and materials, or at total material input, output and throughput (Figure 1). Nevertheless, all of these analyses use the accounting of material inputs and outputs of processes in a quantitative manner, and many of them apply a system or chain perspective. Factsheets Series on 3R Policy Indicators This project is conducted by the Asia Resource Circulation Policy Research Group, a collaborative research group focused on policy research on 3R promotion in Asia; coordinated by IGES with input from researchers from IGES, IDE-JETRO, NIES, University of Malaya, Asia Institute of Technology, Bandung Institute of Technology, Tokyo Institute of Technology and UNCRD.