Article Title: the Industrial Workers of the World in Nebraska, 1914-1920

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter One: Introduction

CHANGING PERCEPTIONS OF IL DUCE TRACING POLITICAL TRENDS IN THE ITALIAN-AMERICAN MEDIA DURING THE EARLY YEARS OF FASCISM by Ryan J. Antonucci Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2013 Changing Perceptions of il Duce Tracing Political Trends in the Italian-American Media during the Early Years of Fascism Ryan J. Antonucci I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: Ryan J. Antonucci, Student Date Approvals: Dr. David Simonelli, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Brian Bonhomme, Committee Member Date Dr. Martha Pallante, Committee Member Date Dr. Carla Simonini, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Associate Dean of Graduate Studies Date Ryan J. Antonucci © 2013 iii ABSTRACT Scholars of Italian-American history have traditionally asserted that the ethnic community’s media during the 1920s and 1930s was pro-Fascist leaning. This thesis challenges that narrative by proving that moderate, and often ambivalent, opinions existed at one time, and the shift to a philo-Fascist position was an active process. Using a survey of six Italian-language sources from diverse cities during the inauguration of Benito Mussolini’s regime, research shows that interpretations varied significantly. One of the newspapers, Il Cittadino Italo-Americano (Youngstown, Ohio) is then used as a case study to better understand why events in Italy were interpreted in certain ways. -

Tom Dennison, the Omaha Bee, and the 1919 Omaha Race Riot

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Tom Dennison, The Omaha Bee, and the 1919 Omaha Race Riot Full Citation: Orville D Menard, “Tom Dennison, The Omaha Bee, and the 1919 Omaha Race Riot,” Nebraska History 68 (1987): 152-165. URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/1987-4-Dennison_Riot.pdf Date: 2/10/2010 Article Summary: In the spring of 1921 Omahans returned James Dahlman to the mayor’s office, replacing Edward P Smith. One particular event convinced Omaha voters that Smith and his divided commissioners must go in order to recapture the stability enjoyed under political boss Tom “the Old Man” Dennison and the Dahlman administration. The role of Dennison and his men in the riot of September 26, 1919, remains equivocal so far as Will Brown’s arrest and murder. However, Dennison and the Bee helped create conditions ripe for the outbreak of racial violence. Errata (if any) Cataloging -

When Workers Stopped Seattle 7/21/19, 10�59 AM When Workers Stopped Seattle

When Workers Stopped Seattle 7/21/19, 10)59 AM When Workers Stopped Seattle BY CAL WINSLOW The Seattle General Strike of 1919 is a forgotten and misunderstood part of American history. But it shows that workers have the power to shut down whole cities — and to run them in our interests. On February 6, 1919, at 10 AM, Seattle’s workers struck. All of them. The strike was in support of roughly 35,000 shipyard workers, then in conflict with the city’s shipyard owners and the federal government’s US Shipping Board, the latter still enforcing wartime wage agreements. Silence settled on the city. “Nothing moved but the tide,” recalled the young African American, Earl George, just demobilized at nearby Camp Lewis.1 Seattle’s workers simply put down their tools. It was, however, no ordinary strike. There had been nothing like it in the United States before, nor since. In doing so, they virtually took control of the city. Anna Louise Strong, writing in the Union Record, announced that labor “will feed the People … Labor will care for the babies and the sick… Labor will preserve order …”2 And indeed it did, for five February days. Seattle’s Central Labor Council (CLC), representing 110 unions, all affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL), called the general strike. The Union Record reported 65,000 union members on strike. Perhaps as many as 100,000 working people participated; the strikers were joined by unorganized workers, unemployed workers, and family members. The strike rendered the authorities virtually powerless. There were soldiers in the city, and many more at nearby Camp Lewis, not to mention thousands of newly enlisted, armed deputies — but to unleash these on a peaceful city? The regular police were reduced to onlookers; the generals hesitated. -

Justice Crucified* a Synopsis, Chronology, and Selective Bibliography of the Sacco and Vanzetti Case

Differentia: Review of Italian Thought Number 8 Combined Issue 8-9 Spring/Autumn Article 21 1999 Remember! Justice Crucified: A Synopsis, Chronology, and Selective Bibliography Gil Fagiani Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.library.stonybrook.edu/differentia Recommended Citation Fagiani, Gil (1999) "Remember! Justice Crucified: A Synopsis, Chronology, and Selective Bibliography," Differentia: Review of Italian Thought: Vol. 8 , Article 21. Available at: https://commons.library.stonybrook.edu/differentia/vol8/iss1/21 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Academic Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Differentia: Review of Italian Thought by an authorized editor of Academic Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Remember! Justice Crucified* A Synopsis, Chronology, and Selective Bibliography of the Sacco and Vanzetti Case Gil Fagiani ____ _ The Enduring Legacy of the Sacco and Vanzetti Case Two Italian immigrants, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, became celebrated martyrs in the struggle for social justice and politi cal freedom for millions of Italian Americans and progressive-minded people throughout the world. Having fallen into a police trap on May 5, 1920, they eventually were indicted on charges of participating in a payroll robbery in South Braintree, Massachusetts in which a paymas ter and his guard were killed. After an unprecedented international campaign, they were executed in Boston on August 27, 1927. Intense interest in the case stemmed from a belief that Sacco and Vanzetti had not been convicted on the evidence but because they were Italian working-class immigrants who espoused a militant anarchist creed. -

Industrial Workers of the World from the 36Th and Madison Store August Charles Fostrom, and Evan Winterscheidt

A new model for building Growing workers’ rebellion international solidarity? knows no borders Zapatistas call for grassroots, Bosses, who needs them? nonelectoral movement of Chinese, South Korean & Serbian communities in resistance 4-5 workers seize workplaces 12 Starbucks fires 3 IWWs Industrial for union organizing In its latest effort to crush the growth England. David Bleakney, a national represen- of the Starbucks Workers Union, Starbucks tative of the 55,000-member Canadian Union has fired three IWW members as part of of Postal Workers, has written CEO Howard a stepped-up campaign of intimidation of Schultz, demanding the reinstatement of the union supporters. three fires workers and warning that if he does Charles Fostrom, a worker at New York’s not receive a satisfactory reply by August 17 57th & Lexington Starbucks, was fired July he will write all CUPW locals to inform them Worker 11 was fired for “insubordination” after he of the situation. refused illegal orders to work off the clock. On July 29, Starbucks workers, other Evan Winterscheidt, a two-year veteran at the IWW members, and supporters from Make 14th & 6th Avenue Starbucks, was fired July The Road By Walking, CODA and NMASS 18 after a minor dispute with a coworker. picketed in support of fired workers Joe Agins OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER OF THE IWW organizer Daniel Gross was fired Jr. (fired some months ago for union activity), INDUSTRIAL WORKERS OF THE WORLD from the 36th and Madison store August Charles Fostrom, and Evan Winterscheidt. 5 for urging district manager Allison Marx Organizing continues despite the firings. September 2006 #1686 Vol. -

International Support for Starbucks Workers

NLRB strips more In November We Remember workers of labor rights workers’ history & martyrs Working “supervisors” lose IWW founder William Trautmann, right to unionize, engaged in Brotherhood of Timber Workers, concerted activity on job 4 Victor Miners’ Hall, and more 5-8 Industrial International support for Starbucks workers As picket lines and other actions reach new Starbucks locations across the United States and the world every week, the coffee giant has told workers it is raising starting pay in an effort to blunt unionization efforts. In Chicago, where workers at a Logan Worker Square store demanded IWW union recogni- tion August 29, Starbucks has raised starting pay from $7.50 an hour to $7.80. After six months, Chicago baristas who receive favor- able performance reviews will make $8.58. Picket lines went up at Paris Starbucks OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER OF THE In New York City, where Starbucks or- anti-union campaign. UAW Local 2320 in ganizing began, baristas will make $9.63 an Brooklyn has told Starbucks that its members INDUSTRIAL WORKERS OF THE WORLD hour after six months on the job and a favor- will not drink their coffee until the fired November 2006 #1689 Vol. 103 No. 10 $1.00 / 75 p able performance review. Senior baristas will unionists are reinstated. Several union locals, receive only a ten-cent raise to discourage student groups and the National Lawyers long-term employment. Similar raises are Guild have declared they are boycotting Star- being implemented across the country. bucks in solidarity with the fired workers. Talkin’ Union Meanwhile, the National Labor Relations In England, Manchester Wobblies pick- B Y N I C K D R I E dg ER, WOBBLY D ispatC H Board continues its investigation into the fir- eted a Starbucks in Albert Square Sept. -

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: the 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike By Leigh Campbell-Hale B.A., University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 1977 M.A., University of Colorado, Boulder, 2005 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado and Committee Members: Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas G. Andrews Mark Pittenger Lee Chambers Ahmed White In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History 2013 This thesis entitled: Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike written by Leigh Campbell-Hale has been approved for the Department of History Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas Andrews Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii Campbell-Hale, Leigh (Ph.D, History) Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike Dissertation directed by Associate Professor Phoebe S.K. Young This dissertation examines the causes, context, and legacies of the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike in relationship to the history of labor organizing and coalmining in both Colorado and the United States. While historians have written prolifically about the Ludlow Massacre, which took place during the 1913- 1914 Colorado coal strike led by the United Mine Workers of America, there has been a curious lack of attention to the Columbine Massacre that occurred not far away within the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike, led by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). -

Politics and the 1920S Writings of Dashiell Hammett 77

Politics and the 1920s Writings of Dashiell Hammett 77 Politics and the 1920s Writings of Dashiell Hammett J. A. Zumoff At first glance, Dashiell Hammett appears a common figure in American letters. He is celebrated as a left-wing writer sympathetic to the American Communist Party (CP) in the 1930s amid the Great Depression and the rise of fascism in Europe. Memories of Hammett are often associated with labor and social struggles in the U.S. and Communist “front groups” in the post-war period. During the period of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anti-Communism, Hammett, notably, refused to collaborate with the House Un-American Activities Committee’s (HUAC) investigations and was briefly jailed and hounded by the government until his death in 1961. Histories of the “literary left” in the twentieth century, however, ignore Hammett.1 At first glance this seems strange, given both Hammett’s literary fame and his politics. More accurately, this points to the difficulty of turning Hammett into a member of the “literary left” based on his literary work, as opposed to his later political activity. At the same time, some writers have attempted to place Hammett’s writing within the context of the 1930s, some even going so far as to posit that his work had underlying left-wing politics. Michael Denning, for example, argues that Hammett’s “stories and characters . in a large part established the hard-boiled aesthetic of the Popular Front” in the 1930s.2 This perspective highlights the danger of seeing Hammett as a writer in the 1930s, instead of the 1920s. -

Cohen, Michael. “The Ku Klux Government”: Vigilantism, Lynching

JSR_v01i:JSR 12/20/06 8:14 AM Page 31 “The Ku Klux Government”: Vigilantism, Lynching, and the Repression of the IWW ■ Michael Cohen, University of California, Berkeley It is almost always the case that a “spontaneous” movement of the subaltern classes is accompanied by a reactionary movement of the right-wing of the dom- inant class, for concomitant reasons. An economic crisis, for instance, engenders on the one hand discontent among the subaltern classes and spontaneous mass movements, and on the other conspiracies among the reactionary groups, who take advantage of the objective weakening of the government in order to attempt coup d’Etat. —Antonio Gramsci 1 When the true history of this decade shall be written in other and less troubled times; when facts not hidden come to light in details now rendered vague and obscure; truth will show that on some recent date, in a secluded office on Wall Street or luxurious parlor of some wealthy club on lower Manhattan, some score of America’s kings of industry, captains of commerce and Kaisers of finance met in secret conclave and plotted the enslavement of millions of workers. Today details are obscured. The paper on which these lines are penciled is criss-crossed by the shadow of prison bars; my ears are be-set by the clang of steel doors, the jangle of fetters and the curses of jail guards. Truth, before it can speak, is stran- gled by power. Yet the big fact looms up, like a mountain above the morning mists; organ- ized wealth has conspired to enslave Labor, and—in enforcing its will—it stops at nothing, not even midnight murders and wholesale slaughter. -

America's Biggest Mass Trial, the Rise of the Justice Department, and the Fall of the IWW

H-HOAC Review: Shapiro on Strang, Keep the Wretches in Order: America's Biggest Mass Trial, the Rise of the Justice Department, and the Fall of the IWW Discussion published by John Haynes on Monday, August 9, 2021 Dean A. Strang. Keep the Wretches in Order: America's Biggest Mass Trial, the Rise of the Justice Department, and the Fall of the IWW. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2019. 344 pp. $36.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-299-32330-1. Reviewed by Shelby Shapiro (Independent Scholar)Published on H-Socialisms (August, 2021) Commissioned by Gary Roth (Rutgers University - Newark) Printable Version: https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=56024 Destroying the IWW Interest in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), or Wobblies, seems to come in waves: the 1950s saw Fred Thompson’s The I.W.W.: Its First Fifty Years (1955) while the 1960s brought Joyce Kornbluh’s Rebel Voices: An IWW Anthology (1964), Robert Tyler’s Rebels of the Woods: The I.W.W. in the Pacific Northwest (1967), Patrick Renshaw’s The Wobblies: The Story of the IWW and Syndicalism in the United States (1967), Ian Turner’s Sydneys’s Burning (1967), and Melvyn Dubofsky’s We Shall Be All (1969), to cite but a few. Entries for the twenty-first century include Lucien van der Walt’s PhD dissertation, “Anarchism and Syndicalism in South Africa, 1904-1921: Rethinking the History of Labour and the Left” (2007); Wobblies of the World: A Global History of the IWW, edited by Peter Cole, David Struthers, and Kenyon Zimmer (2017), and Peter Cole’sBen Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly(2021). -

A Rip in the Social Fabric: Revolution, Industrial Workers of the World, and the Paterson Silk Strike of 1913 in American Literature, 1908-1927

i A RIP IN THE SOCIAL FABRIC: REVOLUTION, INDUSTRIAL WORKERS OF THE WORLD, AND THE PATERSON SILK STRIKE OF 1913 IN AMERICAN LITERATURE, 1908-1927 ___________________________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ___________________________________________________________________________ by Nicholas L. Peterson August, 2011 Examining Committee Members: Daniel T. O’Hara, Advisory Chair, English Philip R. Yannella, English Susan Wells, English David Waldstreicher, History ii ABSTRACT In 1913, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) led a strike of silk workers in Paterson, New Jersey. Several New York intellectuals took advantage of Paterson’s proximity to New York to witness and participate in the strike, eventually organizing the Paterson Pageant as a fundraiser to support the strikers. Directed by John Reed, the strikers told their own story in the dramatic form of the Pageant. The IWW and the Paterson Silk Strike inspired several writers to relate their experience of the strike and their participation in the Pageant in fictional works. Since labor and working-class experience is rarely a literary subject, the assertiveness of workers during a strike is portrayed as a catastrophic event that is difficult for middle-class writers to describe. The IWW’s goal was a revolutionary restructuring of society into a worker-run co- operative and the strike was its chief weapon in achieving this end. Inspired by such a drastic challenge to the social order, writers use traditional social organizations—religion, nationality, and family—to structure their characters’ or narrators’ experience of the strike; but the strike also forces characters and narrators to re-examine these traditional institutions in regard to the class struggle. -

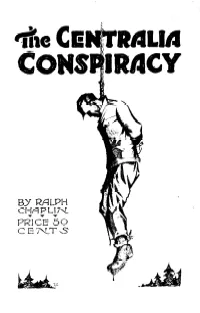

C464c4 1920.Pdf

l11111111111111111111llllllllllllllllllnllnlliilllullululllullllllllulllllllllllllllllllilllilllllllllllllllllllullllllllllllllllulllulull~lllllulllllllluulll~lnlulllnlllulllllllllullilllill~lllllulllllllu~nU 6 e a aongue of JFlam q The martyr cannot be dishonored. Every lash inflicted is a tongue of flame; every prison a more illustrious abode; every burned book or house en- lightens the world; every suppres- sed or expunged word reverberates through the earth from side to side. The minds of men are at last aroused; reason looks out and justifies her own, and malice finds all her work is ruin. It is the whipper who is whipped and the tyrant who is undone.-Emerson. 8 . I1III~llUlll~ll~IIllUllllUlll~lllUUUl~llllUllllUlllllUllllllllllllllUllllllllillll~lllllllliIIUIIIIIIIIIIIIIHIIIlllllll!lllllllllllilllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll~ MURDER OR SELF-DEFENSE? HIS BOOKLET is not an apology for murder. It is an honest effort to unravel the tangled mesh of circumstances that led up to the Armistice Day tragedy in Centralia, Washington. The writer is one of those who believe that the tak- ing of human life is justifiable .only in self-defense. Even then the act is a horrible reversion to the brute-to the low plane of savagery. Civilization, to be worthy of the name, must afford other methods of settling human differences than those of blood letting. The nation was shocked on November 11, 1919, to read of the killing of four American Legion men by members of the In- dustrial Workers of the World in Centralia. The capitalist news- papers announced to the world that these unoffending paraders were killed in cold blood-that they were murdered from ambush without’provocation of any kind. If the author were convinced that there was even a slight possibility of this being true, he would not raise ‘his voice to defend the perpetrators of such a coward1 y crime.