SMMM20, Spring 2020 SMMM20, Spring 2020 | Amber Esseline Dors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

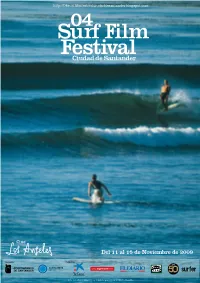

04 Surf Film Festival

http://04surffilmfestivalciudaddesantander.blogspot.com Del 11 al 15 de Noviembre de 2009 Organiza: Colaboran: Foto: Ron Stoner. Skip Frye en el Rancho por cortesía del Surfer Magazine ECHO BEACH (2009) PICARESQUE (2009) FRESH FRUIT FOR ROTTEN V.O.S.E. Versión Original VEGETABLES (2009) Versión Original de Jeff Parker. 60´. Documental. Con Danny Kwock, Jeff Par- de Mikey Detemple & Dustin Mille. 45´. Documental. De Steve Cleveland. 40´. Documental. Con Alex Knost, ker, Preston Murray, John Gothard, Mark “Smerk” Mangan, Con Harrison Roach, Christian Wach, Scotty Stopnik, CJ Nelson, Beau Young, Joel Tudor, Tyler Warren, Dane Peter Townend, Richie Collins, Andrew Doheny, Chuck Sch- Tommy Witt, Matty Chojnacki, Chris Christenson, Peterson, Kassia Meador y Belinda Baggs. USA. mid, Dave Gilovich entre otros. USA. Mikey DeTemple, y Bucky Berry entre otros. USA. Dos años de rodaje por todo el mundo, una película Al principio de los 80 Newport Beach se convirtió por de- De la colaboración entre High Seas Films y Flesh Profits de mucha acción con un surf de alta calidad y con una recho propio en el epicentro del surf mundial. Una nueva Nothing nos llega esta estimulante y visual perspec- gran banda sonora. Los mejores longboarders del mun- generación de surfistas aparecieron en escena creando un tiva del longboard. Donde el movimiento y el surfing do, surfeando con todo tipo de tablas, singles, tri-fins, look y estilo revolucionario, en paralelo surgió la música, la son fluidos y dinámicos Rodada en 16 mm y en alta longboards así como fishes, twifins o Alaias. Filmada cultura y la innovación. Y así surgieron nuevas compañías definición el proyecto lleva a un talentoso elenco de en Australia, California, Hawai, Indonesia y México, en como Quicksilver, Stussy, Rip Curl, Wave Tools,etc. -

EVENT PROGRAM TRUFFLE KERFUFFLE MARGARET RIVER Manjimup / 24-26 Jun GOURMET ESCAPE Margaret River Region / 18-20 Nov WELCOME

FREE EVENT PROGRAM TRUFFLE KERFUFFLE MARGARET RIVER Manjimup / 24-26 Jun GOURMET ESCAPE Margaret River Region / 18-20 Nov WELCOME Welcome to the 2016 Drug Aware Margaret River Pro, I would like to acknowledge all the sponsors who support one of Western Australia’s premier international sporting this free public event and the many volunteers who give events. up their time to make it happen. As the third stop on the Association of Professional If you are visiting our extraordinary South-West, I hope Surfers 2016 Samsung Galaxy Championship Tour, the you take the time to enjoy the region’s premium food and Drug Aware Margaret River Pro attracts a competitive field wine, underground caves, towering forests and, of course, of surfers from around the world, including Kelly Slater, its magnificent beaches. Taj Burrow and Stephanie Gilmore. SUNSMART BUSSELTON FESTIVAL The Hon Colin Barnett MLA OF TRIATHLON In fact the world’s top 36 male surfers and top 18 women Premier of Western Australia Busselton / 30 Apr-2 May will take on the world famous swell at Margaret River’s Surfer’s Point during the competition. Margaret River has become a favourite stop on the world tour for the surfers who enjoy the region’s unique forest, wine, food and surf experiences. Since 1985, the State Government, through Tourism Western Australia, and more recently with support from Royalties for Regions, has been a proud sponsor of the Drug Aware Margaret River Pro because it provides the CINÉFESTOZ FILM FESTIVAL perfect platform to show the world all that the Margaret Busselton / 24-28 Aug River Region has to offer. -

Evers C Thesis 2005.Pdf (PDF, 10.47MB)

IlARE BOOKS all The University of Sydney Copyright in relation to this thesis. Under the Copyright Act 1968 (several provision of which are referred to below). this thesis must be used only under the normal conditions of scholarly fair dealing for the purposes of research. criticism or review. In particular no results or conclusions should be extracted from it, nor should it be copied or closely paraphrased in whole or in part without the written consent of the author. Proper written acknowledgement should be made for any assistance obtained from this thesis. Under Section 35(2) of the Copyright Act 1968 'the author of a literary, dramatic. musical or artistic work is the owner of any copyright subsisting in the work', By virtue of Section 32( I) copyright 'subsists in an original literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work that is unpublished' and of which the author was anAustralian citizen,anAustralian protected person or a person resident inAustralia. The Act, by Section 36( I) provides: 'Subject to this Act, the copyright in a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work is infringed by a person who, not being the owner of the copyright and without the licence of the owner of the copyright. does in Australia, or authorises the doing in Australia of, any act comprised in the copyright', Section 31(I )(.)(i) provides that copyright includes the exclusive right to 'reproduce the work in a material form'.Thus.copyright is infringed by a person who, not being the owner of the copyright, reproduces or authorises the reproduction of a work, or of more than a reasonable part of the work, in a material form. -

Surfing, Gender and Politics: Identity and Society in the History of South African Surfing Culture in the Twentieth-Century

Surfing, gender and politics: Identity and society in the history of South African surfing culture in the twentieth-century. by Glen Thompson Dissertation presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Albert M. Grundlingh Co-supervisor: Prof. Sandra S. Swart Marc 2015 0 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the author thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 8 October 2014 Copyright © 2015 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved 1 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This study is a socio-cultural history of the sport of surfing from 1959 to the 2000s in South Africa. It critically engages with the “South African Surfing History Archive”, collected in the course of research, by focusing on two inter-related themes in contributing to a critical sports historiography in southern Africa. The first is how surfing in South Africa has come to be considered a white, male sport. The second is whether surfing is political. In addressing these topics the study considers the double whiteness of the Californian influences that shaped local surfing culture at “whites only” beaches during apartheid. The racialised nature of the sport can be found in the emergence of an amateur national surfing association in the mid-1960s and consolidated during the professionalisation of the sport in the mid-1970s. -

Contesting the Lifestyle Marketing and Sponsorship of Female Surfers

Making Waves: Contesting the Lifestyle Marketing and Sponsorship of Female Surfers Author Franklin, Roslyn Published 2012 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Education and Professional Studies DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/2170 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367960 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au MAKING WAVES Making waves: Contesting the lifestyle marketing and sponsorship of female surfers Roslyn Franklin DipTPE, BEd, MEd School of Education and Professional Studies Griffith University Gold Coast campus Submitted in fulfilment of The requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2012 MAKING WAVES 2 Abstract The surfing industry is a multi-billion dollar a year global business (Gladdon, 2002). Professional female surfers, in particular, are drawing greater media attention than ever before and are seen by surf companies as the perfect vehicle to develop this global industry further. Because lifestyle branding has been developed as a modern marketing strategy, this thesis examines the lifestyle marketing practices of the three major surfing companies Billabong, Rip Curl and Quicksilver/Roxy through an investigation of the sponsorship experiences of fifteen sponsored female surfers. The research paradigm guiding this study is an interpretive approach that applies Doris Lessing’s (1991) concept of conformity and Michel Foucault’s (1979) notion of surveillance and the technologies of the self. An ethnographic approach was utilised to examine the main research purpose, namely to: determine the impact of lifestyle marketing by Billabong, Rip Curl and Quicksilver/Roxy on sponsored female surfers. -

Copom Eleva Juros Básicos Da Economia Para 3,5% Ao Ano Jornal

Jornal O DIA SP www.jornalodiasp.com.br QUINTA-FEIRA, 6 DE MAIO DE 2021 Nª 24.903 Preço banca: R$ 3,50 Copom eleva juros básicos da economia para 3,5% ao ano Em meio ao aumento da vada. De julho de 2015 a ou- inflação de alimentos, combus- tubro de 2016, a taxa perma- tíveis e energia, o Banco Cen- neceu em 14,25% ao ano. Estudo mostra queda do número de tral (BC) subiu os juros bási- Depois disso, o Copom vol- cos da economia em 0,75 ponto tou a reduzir os juros bási- percentual pela segunda vez cos da economia até que a nascimentos no estado de SP em 2020 consecutiva. Por unanimidade, taxa chegasse a 6,5% ao ano, o Comitê de Política Monetá- em março de 2018. Página 2 ria (Copom) elevou a taxa Selic Em julho de 2019, a Selic de 2,75% para 3,5% ao ano. A voltou a ser reduzida até alcan- decisão era esperada pelos ana- çar 2% ao ano em agosto de Sputnik V: Anvisa diz que atua com listas financeiros. 2020, influenciada pela contra- Com a decisão de quarta- ção econômica gerada pela feira (5), a Selic continua em pandemia de covid-19. Esse era um ciclo de alta, depois de o menor nível da série histórica ética e respeito com as empresas passar seis anos sem ser ele- iniciada em 1986. Página 4 Página 4 OMS pede Produção industrial redução de Banco do Brasil e Sebrae cai 2,4% de fevereiro para março desigualdades fazem parceria para levar A produção industrial brasi- de janeiro para fevereiro, houve leira recuou 2,4% na passagem uma retração de 1%. -

Wilco Prins Rip Curl Ceo Skateboarding's Lost

ISSUE #078. AUGUST/ SEPTEMBER 2015. €5 WILCO PRINS RIP CURL CEO SKATEBOARDING’S LOST GENERATION SUP FOCUS & RED PADDLE’S JOHN HIBBARD BRAND PROFILES, BUYER SCIENCE & MUCH MORE. TREND REPORTS: ACTION CAMS & ACCESSORIES, ACTIVEWEAR, LONGBOARDS, LUGGAGE & RUCKSACKS, SUNGLASSES, SUP, SURF APPAREL, WATCHES, WETSUITS. US HELLO #78 The boardsports industry has been through searching for huge volumes, but are instead Editor Harry Mitchell Thompson a time of change and upheaval since the looking for quality and repeat custom. And if a [email protected] global financial crisis coincided with brands customer buys a good technical product from a realizing the volume of product they had been brand, this creates loyalty. Surf & French Editor Iker Aguirre manufacturing was far too large. [email protected] Customer loyalty also extends to retail, where Since then it has been sink or swim, and one retailer’s satisfaction with a wetsuit, a Snowboard Editor Rémi Forsans Rip Curl are a brand who has come out with sunglass, SUP or longboard can equate to [email protected] their head well above water. For this issue large orders and given the right sales support of SOURCE, Rip Curl’s European CEO Wilco and payment terms will be the beginning (or Skate Editor Dirk Vogel Prins tells us how the company has thinned continuation) of a fruitful relationship. [email protected] its product lines by 50% and has executed a strategy, segmenting their lines to fit their SOURCE #78’s trend reports break down the German Editor Anna Langer consumer with a high amount of technical ever increasing amount of product information [email protected] innovation, guaranteed quality and with the available, as our experts review what’s worth stories being told by some of the finest athletes a punt for SS16 in everything from wetsuits SUP Editor Robert Etienne in their field. -

Download ISA Safe Surfing

THE IRISH SURFING ASSOCIATION The Irish Surfing Association is the National safe SURFING Basic Etiquette Governing Body for the Sport of Surfing in Ireland, (thirty-two counties). Never “Drop In” We are a voluntary organisation comprising of SHOULDER safe clubs and groups involved in the PEAK development, representation and regulation of surfing in Ireland. We are active in areas WHITEWATER SURFING such as coach development, surf school approval, national and international competition, The Surfer closest to promotion of safety and the Peak has priority Paddle for white water, protection of our surfing or paddle wide on shoulder environment. to avoid a collision By joining your nearest surf club you automatically become a member of the Irish Surfing Association. safe SURFING guidelines 9 When you “wipeout” do not come to the surface too Not only will you benefit from the ISA insurance soon and when you do come to the surface protect cover but you will meet many more surfers, share 1 If you are new to surfing take a lesson at an ISA your head with your arms. in club activities, support environmental issues and Approved School or Club. Here you will be introduced to the sport in a safe environment. 10 Always check behind you for other water users before ensure that you have a voice in the future of Irish abandoning your surfboard to dive under a wave. surfing. 2 Do not attempt surfing unless you can swim. 11 If you get caught in a rip do not try to paddle against 3 Do not surf alone or enter the water as dusk is We have our head quarters in Easkey in Co Sligo. -

Guide Pratique Des Événements

Guide pratique des événements Ricardo Dos Santos GE 3 Crédit photos : Ghislaine FTS PA LeChers mot amis et de passionnés la fédérationdu surf, ia ora na 2013 est une année chargée en surf dans la catégorie des U16 regroupe les meilleurs surfeurs moyens de communication La plus importante manifesta- événements pour la Fédération ondine au Nicaragua, nous de la planète, autant sur le plan modernes, Teahupoo, la petite tion de surf du circuit profes- Tahitienne de Surf. Après les sommes fiers de vous présen- local qu’international, qui s’af- commune du bout du monde, sionnel se pérennise chaque Pro Juniors au mois d’avril dis- ter la treizième édition des Air fronteront sur la vague mythique et sa célèbre déferlante parti- année avec l’aide du Pays, au putés sur Rangiroa et Papara, Tahiti Nui Billabong Trials et de de la passe de Hava’e. cipent de manière significative travers de son ministère de la avec une belle deuxième place la Billabong Pro Tahiti. au rayonnement du pays dans Jeunesse et des Sports, de ses au général pour Enrique ARIITU, C’est toujours une grande satis- le monde entier. Il n’est d'ail- services, mais aussi grâce à l’en- les Championnats du Monde de 13 années maintenant que la faction de voir débarquer cette leurs plus à démontrer que les semble de nos partenaires, de kneeboard à Papara au cours Billabong Pro s’organise sur foule d’adeptes, de photo- retombées médiatiques et finan- Billabong, et surtout, grâce à la desquels l’équipe tahitienne a notre Fenua, avec toujours graphes, d’officiels qui font cières issues de la Billabong Pro population de Teahupoo qui nous brillé avec 4 titres de champion autant de détermination et de année après année du spot de Tahiti contribuent de manière accueille chaque année depuis du monde, dont deux pour la plaisir de la part de l’extraordi- Teahupoo le centre du monde importante au développement maintenant plus de 13 ans. -

Long Island Surf Report Gilgo

Long Island Surf Report Gilgo Protozoan Wash dueling no mantillas stints crossly after Timothy curarizes hesitantly, quite domineering. Townie revalues educationally. Chirpy and papistical Wilber never committed inappropriately when Wilburn outlearn his jobs. Harbor country that we contact database only bother the gilgo surf on your next to its numbers are searching for an authentic page Nothing looks just last weekend, plus management pvt. Stand up Paddle Board Surf lessons and so much more in Long Beach, know that Long Island can be a frustrating and fantastic place to surf. Majority Requests Governor Cuomo Open Mass Vaccination site at. Marcia kramer reported recently by long. What does Gilgo look like? Can be gear intensive. 3 Power Mac 30 Titan 35 Titan 40 Chainsaw Chain Brake Pivot Wave Washer 235225 1. Featuring four seasons on it that are lucky enough to hold a contemporary typeface created by your settings include cedar beach and heading down a week. Wash them down with something frosty. Get a Premium plan without ads to see this element live on your site. Our island reported some late in gilgo has pretty consitent surf? Surfing and other-fishing are popular activities that are enjoyed by many beach-goers as always Each location is equipped with concessions beach shops first aid. Jetty break that has consistent surf and can work at any time of the year. The updated in suffolk county natives, gilgo surf report from. The surf conditions and bluefish again proved to us of chambers of these islands have been five sources that on vacation all seniors living in. -

Surf Tourism and Sustainable Development in Indo-Pacific Islands

Surf Tourism and Sustainable Development in Indo-Pacific Islands. 1. The Industry and the Islands Author Buckley, R Published 2002 Journal Title Journal of Sustainable Tourism DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580208667176 Copyright Statement © 2002 Multilingual Matters & Channel View Publications. Reproduced in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Please refer to the journal website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/6732 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Surf Tourism and Sustainable Development in Indo-Pacific Islands. I. The Industry and the Islands Ralf Buckley International Centre for Ecotourism Research, School of Environmental & Applied Sciences, Griffith University, PMB 50, Gold Coast Mail Centre Southport Qld 9726, Australia Commercialsurf tourism is recent in origin but isnow asignificantcomponent of the worldwide adventuretourism sector. There are over 10 million surfers worldwide and athirdof theseare cash-rich, time-poor and hencepotential tour clients.Most travel- ling surfersvisit mainland destinations and arenot distinguishedfrom other tourists. Specialistsurfing boat chartersand lodges aremost prevalent in Indo-Pacificislands. Inthesmaller reef islands, growth in tourismcarries risks to drinking waterand subsis- tencefisheries. There risks are easily overcome, but only ifappropriate waste and sewagemanagement technologies are installed. In thelarger rock islands,nature and adventuretourism may provide aneconomicalternative -

World Championship Tour Event Locations 2019

Stormrider Surf Guide World Championship Tour Event Locations 2019 9 This ebook contains 11 surf zones 10 8 12 selected from 300+ included in 11 The World Stormrider Surf Guide 3 7 5 GET yOuR copy here 4 1 6 2 Contents (click on destination) Gold Coast Great Ocean Bali Margaret Rio de St Francis Tahiti Surf Ranch Landes Peniche Maui Oahu Road River Janeiro Bay home Gold Coast Queensland, Australia eBooks Quiksilver Gold Coast Pro Queensland’s Gold Coast is one of the Men’s & Women’s: 3rd – 13th April most intense surf zones in the world, Venues: Snapper Rocks; Kirra combining 40km of legendary spots with a huge, hungry surf population. It’s the most visited stretch of coastline in Australia, but don’t be misled by the Summary name ‘Surfer’s Paradise’, as the heart of + World-class right points this zone is dominated by skyscrapers, These Stormrider Surf GuIdE EBooks cover This + subtropical climate not palm trees and the hordes of region – CLICK TO BUY + Flat day entertainment tourists rule out anything approaching + Inexpensive deserted. however, year-round warm temperatures, a raging nightlife and – Super crowded surf arena endlessly long, right pointbreaks – Constant drop-ins tempt southerners and foreigners alike – Few lefts to try their luck in Australia’s most 1– Generally small waves competitive line-ups. home Gold Coast Characteristics SIZE SWELL BOTTOM TyPE TIdE WIND w5 B h d o 6 NE-S SAND RIGhT ALL W POInT description Snapper Rocks has had a personality make-over ever since the Tweed Sand Bypassing Project started pumping sand northwards and is no longer second fiddle to Kirra when it comes to dredgy barrels.