Vidlin in the Great War 1914

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shetland Mainland North (Potentially Vulnerable Area 04/01)

Shetland Mainland North (Potentially Vulnerable Area 04/01) Local Plan District Local authority Main catchment Shetland Shetland Islands Council Shetland coastal Summary of flooding impacts Summary of flooding impacts flooding of Summary At risk of flooding • <10 residential properties • <10 non-residential properties • £47,000 Annual Average Damages (damages by flood source shown left) Summary of objectives to manage flooding Objectives have been set by SEPA and agreed with flood risk management authorities. These are the aims for managing local flood risk. The objectives have been grouped in three main ways: by reducing risk, avoiding increasing risk or accepting risk by maintaining current levels of management. Objectives Many organisations, such as Scottish Water and energy companies, actively maintain and manage their own assets including their risk from flooding. Where known, these actions are described here. Scottish Natural Heritage and Historic Environment Scotland work with site owners to manage flooding where appropriate at designated environmental and/or cultural heritage sites. These actions are not detailed further in the Flood Risk Management Strategies. Summary of actions to manage flooding The actions below have been selected to manage flood risk. Flood Natural flood New flood Community Property level Site protection protection management warning flood action protection plans scheme/works works groups scheme Actions Flood Natural flood Maintain flood Awareness Surface water Emergency protection management warning raising plan/study plans/response study study Maintain flood Strategic Flood Planning Self help Maintenance protection mapping and forecasting policies scheme modelling Shetland Local Plan District Section 2 20 Shetland Mainland North (Potentially Vulnerable Area 04/01) Local Plan District Local authority Main catchment Shetland Shetland Islands Council Shetland coastal Background This Potentially Vulnerable Area is There are several communities located in the north of Mainland including Voe, Mossbank, Brae and Shetland (shown below). -

Socio-Economic Baseline Reviews for Offshore Renewables in Scottish Waters

RPA. Marine Scotland Socio-economic Baseline Reviews for Offshore Renewables in Scottish Waters Volume 1: Main Text Report R.1905 September 2012 RPA. Marine Scotland Socio-economic Baseline Reviews for Offshore Renewables in Scottish Waters Volume 2: Figures Report R.1905 September 2012 Marine Scotland Socio-economic Baseline Reviews for Offshore Renewables in Scottish Waters Date: September 2012 Project Ref: R4032/3 Report No: R.1905 © ABP Marine Environmental Research Ltd Version Details of Change Authorised By Date 1 Working Copy C E Brown 02.12.11 2 Final C E Brown 07.02.12 3 Final C E Brown 26.04.12 4 Final C E Brown 28.06.12 5 Final C E Brown 24.09.12 Document Authorisation Signature Date Project Manager: C E Brown Quality Manager: H Roberts Project Director: S C Hull ABP Marine Environmental Research Ltd Quayside Suite, Medina Chambers Town Quay Tel: +44(0)23 8071 1840 SOUTHAMPTON Fax: +44(0)23 8071 1841 Hampshire Web: www.abpmer.co.uk SO14 2AQ Email: [email protected] ABPmer is certified by: All images copyright ABPmer apart from front cover (wave, anemone, bird) and policy & management (rockpool) Andy Pearson www.oceansedgephotography.co.uk Socio-economic Baseline Reviews for Offshore Renewables in Scottish Waters Summary ABP Marine Environmental Research Ltd (ABPmer) and RPA were commissioned by Marine Scotland to prepare a baseline socio-economic review to inform impact assessments of future sectoral plans for offshore wind and wave and tidal energy in Scottish Territorial Waters and waters offshore of Scotland (hereafter „Scottish Waters‟). This report provides a national overview of socio-economic activities together with regional baseline reviews covering the six Scottish Offshore Renewable Energy Regions (SORERs). -

Out and About Around Shetland

Out and About Shetland Areas to visit Some things to see and do Beaches to visit Best places to eat out The white wife, Hermaness, Norwick beach, Easting Unst and Yell Boat Haven, Bobby’s bus beach, West Sandwick Victoria’s Tea Room and LJ’s Diner shelter and Viking Longship and Breckon Sands Brae swimming pool, Voxter Beach at Lunna, Vidlin, Brae and trees, Wigwams, Ronas Hill, Frankie's, Hillswick Hotel, Mid Brae and Fethaland Beach, Back North Mainland Stones of Stofast, Bell Tower Busta House Sand at Lunna and Hams of Roe Kergord trees, Bonhoga Tresta Beach, Raewick Central and the Bonhoga, The Cake Fridge and Braewick Gallery, Michaels Wood, Da beach and Sandsound Westside Café Gairdins at Sand, Gruting beach The Steak House, Island Larder, Isleburgh, The Museum, Playpark, go The Noodle Bar, Peerie Shop Café, Shetland shopping, Aa Fired Up, Sands of Sound and Lerwick, and Lerwick Hotel, Magnos, Fjara, Mareel, Clickimin, Lerwick Bains beach Skippidock, The Dowry, The Fort Chippy, The Library and The Knab Great Wall, The Golden Coach and Saffron Scalloway pool, Hamnavoe Scalloway and lighthouse, Smuggler’s cave, Meal Beach and Minn Burra cake fridge, The Cornerstone and The Burra The Ootpost and Trondra Beach Haaf Farm Sumburgh Lighthouse, West Voe Beach, Jarlshof, Sandwick Leisure Mackenzie’s Farm shop, cake fridge at The South End Levenwick beach, St Centre, playpark and Red Sandwick playpark and Sumburgh Lighthouse Ninians Isle and Spiggie pool of Virkie https://www.shetland.org/visit for more things to see and do Things to do on -

STD Code Book for 1984 Based on Haddenham & Long Crendon Issue 4, 1984

STD Code Book for 1984 Based on Haddenham & Long Crendon Issue 4, 1984 01 London 0207 Burnopfield 0200 Clitheroe 0207 Consett 0200 5 Gisburn 0207 Dipton 0200 6 Slaidburn 0207 Ebchester 0200 7 Bolton-by-Bowland 0207 Edmundbyers 0200 8 Dunsop Bridge 0207 Lanchester (Co Durham) 0202 Bournemouth 0207 Rowlands Gill 0202 Broadstone 0207 Stanley (Co Durham) 0202 Canford Cliffs 0208 Bodmin 0202 Christchurch (Dorset) 0208 Lanivet 0202 Ferndown 0208 81 Wadebridge 0202 Lytchett Minster 0208 82 Cardinham 0202 Parkstone 0208 84 St Mabyn 0202 Poole 0208 86 Trebetherick 0202 Verwood 0208 88 Port Isaac 0202 Wimborne (Dorset) 0209 Camborne 0203 Bedworth 0209 Porthtowan 0203 Chapel End 0209 Portreath 0203 Coventry 0209 Praze 0203 Nuneaton 0209 Redruth 0203 Royal Show 0209 St Day 0203 Wolston 0209 Stithians 0203 33 Keresley (Coventry) 021 Birmingham 0204 Bolton 0220 23 Histon 0204 Farnworth 0220 26 Comberton 0204 Horwich (Lancs) 0220 29 West Wratting 0204 Turton 0220 5 Teversham 0204 81 Belmont Village 0221 22 Limpley Stoke 0204 88 Tottington 0221 4 Trowbridge (4 & 5 fig nos) 0205 Boston (Lincs) 0221 6 Bradford-on-Avon 0205 73 Langrick 0221 7 Saltford (4 fig nos) 0205 78 Stickney 0222 Caerphilly 0205 79 Hubbert's Bridge 0222 Cardiff 0205 84 New Leake 0222 Dinas Powys 0205 85 Fosdyke 0222 Penarth 0205 86 Sutterton 0222 Pentyrch 0206 Colchester 0222 Radyr (Sth Glam) 0206 Great Bentley 0222 Senghenydd 0206 Nayland (Colchester) 0222 Sully 0206 West Mersea 0222 Taffs Well 0206 22 Wivenhoe 0223 Cambridge 0206 28 Rowhedge 0224 Aberdeen 0206 30 Brightlingsea 0224 -

The Control of Sea Lice in Fish

THE CONTROL OF SEA LICE ON FISH FARMS IN SCOTLAND 2013-2015 A REPORT FOR SALMON AND TROUT CONSERVATION SCOTLAND DECEMBER 2015 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Fisheries scientists are increasingly firm in their conclusions that sea lice produced on fish-farms harm wild salmonids, both at an individual and at a population level, making the proper control of sea-lice on fish-farms essential to protect wild fish. Although analysis of control of sea-lice on Scottish fish-farms is severely hampered by the lack of farm-specific sea lice data, publicly available data for 2013 to 2015 shows that the number of Scottish fish-farming regions failing to keep adult female sea lice numbers below the CoGP threshold is on an upward trend. The industry- wide problem with sea lice is increasing and is certainly not under control. The proportion of the total Scottish farms salmon production exceeding CoGP thresholds shows a similar upward trend, with regions representing 60% of Scottish production being over the CoGP threshold of 0.5 adult female lice per fish in May 2015, at the peak of the wild smolt run. There is strong evidence that sea lice numbers on fish farms rise during the second year of production and, in much of Scotland, average adult female sea lice numbers per farmed fish appear to be linked to the cumulative biomass of farmed fish held on the farms. There is evidence of the considerable failure in some regions of available chemical sea lice treatments to limit sea lice numbers on farmed fish to below CoGP thresholds, strongly suggesting that resistance and tolerance to these treatments is becoming widespread. -

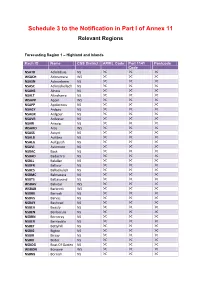

Schedule-3.Pdf (PDF File, 3.1

Schedule 3 to the Notification in Part I of Annex 11 Relevant Regions Forecasting Region 1 – Highland and Islands Exch ID Name CSS District ARIEL Code Part 1141 Postcode Code NSATB Achiltibuie NS WSACH Achnamara WS NSASN Achnasheen NS NSASC Achnashellach NS NSANS Alness NS NSALT Altnaharra NS WSAPP Appin WS NSAPP Applecross NS NSAGY Ardgay NS NSAGR Ardgour NS NSAVR Ardvasar NS NSARI Arisaig NS WSARO Aros WS NSASS Assynt NS NSALB Aultbea NS NSALG Aultguish NS NSAVI Aviemore NS NSBAC Back NS NSBAD Badachro NS NSBLL Balallan NS NSBFR Balfour NS NSBCS Ballachulish NS NSBMC Balmacara NS NSBTS Baltasound NS WSBAV Balvicar WS WSBAB Barbreck WS NSBRK Barrock NS NSBVS Barvas NS NSBAY Bayhead NS NSBEA Beauly NS NSBEN Benbecula NS NSBRN Berneray NS NSBER Berriedale NS NSBET Bettyhill NS NSBIG Bigton NS NSBIR Birsay NS NSBIX Bixter NS NSBOG Boat Of Garten NS WSBON Bonawe WS NSBNS Bornish NS Exch ID Name CSS District ARIEL Code Part 1141 Postcode Code NSBRV Borve NS WSBOW Bowmore WS NSBRA Brae NS NSBSY Bressay NS NSBFD Broadford NS NSBRR Brora NS NSBVO Burravoe NS NSBRY Burray NS WSCAI Cairndow WS NSCGM Cairngorm NS NSCAL Callanish NS WSCAP Campbeltown WS NSCAN Cannich NS NSCAR Carbost NS NSCWY Carloway NS NSCRN Carnan NS WSCAD Carradale WS NSCRB Carrbridge NS NSCBY Castlebay NS NSCTW Castletown NS WSCLA Clachan WS WSCOL Coll WS WSCOY Colonsay WS WSCOE Connel WS -

1005096 Shetland Times.Pdf

APPENDIX 2 CERTIFICATE OF PUBLICATION Please complete this certificate by providing the following details, sign and send it, along with pages of the newspapers that contained the advertisements, to SEPA either by email to registrydingwall(cDsepa.org. uk or in writing to the following address: Registry Department, SEPA, Registry Department, SEPA, Graesser House, Fodderty Way, Dingwall Business Park, Dingwall, IV15 9XB no later than 8 August 2018.. Publications containing advertisement Name of newspaper i Date of publication Edinburgh Gazette 13' July 2018 Shetland Times 13' h July 2018 Declaration ' I hereby certify that notices advertising applications under the Water Environment (Controlled Activities) ( Scotland) Regulations 2011 to vary water use licences, reference numbers CAR/ U1005096 and 1004032, have been published in the newspapers and on the respective dates given above and that pages of the relevant newspapers containing the advertisements are attached. Signature Date 20. 07. 18 Print name Christopher Webb On behalf of Cooke Aquaculture Scotland state corporate body, if applicable) The Shetland Times | Friday, 13th July, 2018 | 29 NOTICESPUBLICPUBLIC NOTICES Water Environment And Water Services ( Scotland) Act MARINE ( SCOTLAND) ACT 2010 2003. Water Environment ( Controlled Activities) ( Scotland) INSTALLATION OF FINFISH FARMS, Regulations 2011 HOGAN AND HOLM OF GRUTING, Applications for variation of authorisations. GRUTING VOE, SHETLAND Marine cage sh farm, Hogan, Gruting Voe, Walls, Shetland. Notice is hereby given that Cooke Aquaculture Scotland has Marine cage sh farm, Holm of Gruting, Gruting Voe, Walls, Shetland applied to the Scottish Ministers of the Scottish Government, Education Maintenance Allowance under Part 4 of the Marine ( Scotland) Act 2010, in respect of An application has been made to the Scottish Environment installation of nsh farms at: Protection Agency (SEPA) by Cooke Aquaculture Scotland Ltd. -

Pioneer Air Reconnaissance of Scottish Seabirds: to Rockall and Back with the RAF in 1941–47 P

Contents Scottish Birds 36:2 (2016) 98 President’s Foreword I. Thomson PAPERS 99 Scottish Birds Records Committee report on rare birds in Scotland, 2014 R.Y. McGowan & C.J. McInerny on behalf of the Scottish Birds Records Committee 121 The role of predation in the decline in the breeding success of Scottish Crested Tits in a coastal pine plantation W.G. Taylor, B. Etheridge & R.W. Summers 135 Colonisation by woodland birds at Carrifran Wildwood: the story so far C.J. Savory OBITUARY 150 Henry Robb (1933–2016) ARTICLES, NEWS & VIEWS 152 Scottish Birdwatchers’ Conference, Peebles, 19 March 2016 160 NEWS AND NOTICES 164 Pioneer air reconnaissance of Scottish seabirds: to Rockall and back with the RAF in 1941–47 P. Holt 168 Breeding Woodcock G.F. Appleton 171 BOOK REVIEWS 173 OBSERVATORIES' ROUNDUP 176 Daffy Duck - Blackdog’s orange-billed scoter N. Littlewood 178 Rufous Turtle Dove, Scalloway, Shetland, November–December 2015 J. Watt 183 Little Swift, Thorntonloch, 31 December 2015 - the first record for Lothian W. Edmond & M. Gladstone 185 Mourning Dove, Lerwick, December 2015–January 2016 - the first record for Shetland A. Taylor SIGHTINGS 188 Scottish Bird Sightings: 1 January to 31 March 2016 S.L. Rivers PHOTOSPOT BC Gyrfalcon S. Duffield 36:2 (2016) Scottish Birds 97 President’s Foreword President’s Foreword We regularly hear bad news stories about Scotland’s birds. Whether it is the latest disastrous breeding season for seabirds in the Northern Isles, the poisoning of a Red Kite on a grouse moor or the continuing declines shown by farmland birds or waders - our birds clearly face significant challenges. -

British Birds Report on Rare Birds in Great Britain in 1994

British Birds Established 1907; incorporating 'The Zoologist', established 1843 Report on rare birds in Great Britain in 1994 Michael J. Rogers and the Rarities Committee, with comments by P. M. Ellis and A. M. Stoddart As this thirty-seventh annual report of the Rarities Committee illustrates, the changing fortunes of rare birds visiting Great Britain continue to be sufficient to stimulate discussion and speculation, and sometimes, indeed, disagreement. Their appeal remains undimmed and the Report aims to meet the needs of the wide variety of interests among rarity enthusiasts. Our principal aim is straightforward: to provide as complete and accurate a record as possible year by year. This can then be used by those responsible for producing county and local bird reports, books, lists and papers, as the 'official' record of rare birds in our islands. The Rarities Committee forms part of an increasing international network of such committees and gains strength from that and from its widespread recognition as a model upon which others are based. We are conscious, of course, of the need to provide interest and entertainment: simply reading a report should be enjoyable in itself, and even ensuring that the names of those people involved in finding and identifying birds are included is something that we take seriously. Then there is what might be called the scientific aim of recording rare birds. This relies on the completeness and accuracy already mentioned and it is the integrity of the Committee and its actions, and the attitude it takes towards reaching difficult decisions, that determines the value of its ultimate product. -

Family Information Directory

Shetland Family Information Directory Information on services and sources of support for families living and working in Shetland 2 Contents Childcare 4 Work and Finance 18 Family Support 21 Community Involvement 30 Family Information 32 Activities and Leisure 38 Services for Young People 43 Health 44 Disclaimer: While we have made every effort to ensure the accuracy of the information in this booklet, we disclaim any warranty or representation, expressed or implied about its accuracy, completeness or appropriateness for a particular purpose. Neither NHS Shetland, Shetland Islands Council not any of their employees are responsible or liable for any claim, loss or damage resulting from its use. These agencies are not responsible for the contents or reliability of the websites listed and do not necessarily endorse the views expressed within them. Inclusion in this Directory shall not be taken as endorsement of any kind. Printed May 2012 3 Family Information Being a parent can be the most challenging and rewarding task anyone will undertake. Access to good quality information about services, activities and sources of support can make a big difference and help you to make informed choices for you and for your family. This Directory has been compiled by organisations in Shetland, who are working to support the well being of families in these islands. It is hoped that families and those working with parents, carers and children will all benefit from this source of information. This information was correct at the time of printing, if you find inaccuracies, or have suggestions for additional information, which would be useful to include, please let us know. -

Shetland Craft Trail Other Outlets

Shetland 5 JANE PORTER-JACOBS 9 NINIAN/JOANNA 13 BURRA BEARS 17 JAMES B THOMASON Other Outlets Craft Trail HUNTER KNITWEAR Shetland Arts & Crafts Veer North A BONHOGA GALLERY Wesidale Mill, ZE2 9LW 1 GLANSIN GLASS T 01595 745750 www.shetlandarts.org B GLOBALYELL LTD Contact: Wendy Inkster, Nonavaar, Levenwick, ZE2 9HX 4 Sellafi rth, Yell, ZE2 9DG Snekkarim, North Lea, Meadows Road, Houss, T 01950 422447 80 Commercial Street, Lerwick, www.jamesthomason.co.uk T 01957 744355 Vidlin, ZE2 9QB ZE1 0DL Burra Isle, ZE2 9LE T 01806 577373 T 01595 859374 Payment: cash, cheque www.globalyell.org E [email protected] T 01595 696655 E [email protected] www.vidlinpottery.shetland.co.uk E [email protected] www.burrabears.co.uk Open: 16th May-29th Aug, www.ninianonline.co.uk garden and studio open C Payment: cash, cheque Payment: cash, credit card Payment: cash, cheque Mon 10am-4pm, Sat 10am-2pm HOSWICK VISITORS also by appointment Open: please phone fi rst Open: Mon-Sat 9am-5.30pm, Open: Open most days but please CENTRE My art is about the way I see and call ahead to avoid disappointment Award winning artist. Imaginative, Contact: Cheryl Jamieson, feel about the Shetland landscape. I Ninian o er an exciting collection The original Shetland Teddy fi gurative, Shetland themes, Hoswick, Hoversta, Uyeasound, Unst, work with watercolour, acrylic and of Shetland knitwear, designed by Bear established 1997. Delightful, landscape, portraits, abstracts, Sandwick, ZE2 9HL ZE2 9DL paper collage Joanna Hunter, pop into their shop collectable, handmade bears collage & Australian themes. T 01957 755311 and studio to feast your eyes on T 01950 431284 the exciting array of colours and produced from recycled traditional E [email protected] Fair Isle knitwear. -

Scottish Natural Heritage FACTS and FIGURES 1996-97

Scottish Natural Heritage FACTS AND FIGURES 1996-97 Working with Scotland’s people to care for our natural heritage PREFACE SNH Facts and Figures 1996/97, contains a range of useful facts and statistics about SNH’s work and is a companion publication to our Annual Report. SNH came into being on 1 April 1992, and in our first Annual Report we published an inventory of Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs). After an interval of five years it is appropriate to now update this inventory. We have also provided a complete Scottish listing of National Nature Reserves, National Scenic Areas, European sites and certain other types of designation. As well as the information on sites, we have also published information on our successes during 1996/97 including partnership funding of projects, details of grants awarded, licences issued and our performance in meeting our standards for customer care. We have also published a full list of management agreements concluded in 1996/97. We hope that those consulting this document will find it a useful and valuable record. We are committed to being open in the way we work and if there is additional information you require, contact us, either at any local offices (detailed in the telephone directory) or through our Public Affairs Branch, Scottish Natural Heritage, 12 Hope Terrace, Edinburgh EH9 2AS. Telephone: 0131 447 4784 Fax: 0131 446 2277. Table of Contents LICENCES 1 Licences protecting wildlife issued from 1 April 1996 to 31 March 1997 under various Acts of Parliament 1 CONSULTATIONS 2 Natural