History of Cuban Cuisine: Food & Drink Section Headliner Arielle Egozi Cubanheritage.Com There Is Nothing Quite Like Eating

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STORE Bahama Deli Inc. Bettolona Italian Restaurant Bierstrasse Beer

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PUBLIC SAFETY SAFE HAVEN PROGRAM MANHATTANVILLE CAMPUS STORE LOCATION Bahama Deli Inc. 3137 Braodway / On the corner of La Salle Street Bettolona Italian Restaurant 3143 Broadway / Off of La Salle Street Bierstrasse Beer Garden 2346 12th Avenue / Off of W 133rd Street Chapati House Simply Indian 3153 Broadway / Off of Tiemann Place Chokolat Café 3187 Broadway / Off of 125th Street Claremont Chemists 3181 Broadway / Off of Tiemann Place C-Town Market*** 560 W 125th Street / Off of Broadway Dinosaur BBQ 700 W 125th Street / On 12th Avenue Duane Reade 568 W 125th Street / Off of Broadway El Porton Mexican Restaurant 3151 Broadway / Btwn La Salle Street & Tiemann Place Fairway Supermarket (FLEX) 2328 12th Avenue / Btwn W 132nd Street & W 133th Street Falafel on Broadway 3151 Broadway / Btwn La Salle Street & Tiemann Place Floridita Cuban Cuisine 2276 12th Avenue / Off of W 125th Street Go! Go! Curry! USA 567 W 125th Street / Off of Broadway Hamilton Pharmacy 3293 Broadway / Off of W 133rd Street Island Burgers and Shakes 3147 Broadway / Btwn La Salle Street & Tiemann Place Jin Ramen Restaurant 3183 Broadway / Off of Tiemann Place Joe's G.H. Deli 3161 Broadway / Off of Tiemann Place Kuro Kuma Espresso & Coffee 121 La Salle Street / Off of Broadway Lala Wine & Liquor 566 W 125th Street / Off of Broadway La Salle Dumpling Room*** 341 Broadway / Off of La Salle Street McDonald's Restaurant 600 W 125th Street / On Broadway Oasis Jimma Juice Bar 3163 Broadway / Off of Tiemann Place Shell Gasoline Station 3260 Broadway / Off -

Appetizers Entrees Desserts

Appetizers YUCCA FRITA Mojo crema 6 EMPANADAS DE PICADILLO Guayaba sauce 10 TOSTONES CON ROPA VIEJA Shredded beef with tostones 9 CHICHARRONES DE POLLO Cuban-spiced fried chicken thighs 10 ENSALADA Romaine, tomatoes, onion, cilantro vinaigrette 10 Add chicken, pork or rock shrimp 5 Entrees ROPA VIEJA Shredded beef, rice, tostones 19 CERDO ASADO Guava-mojo marinated pork, rice, beans 21 POLLO AL SARTEN Seared chicken breast, heirloom tomato sauce, congri 25 ESCABECHE DE CHILLO Whole Snapper, white rice 25 BISTEC Mojo-marinaded steak, pickled onions, poquito peppers 28 HAMBURGUESA Triple blend, swiss cheese, sliced pickles, crispy onions with mojo-pulled pork 18 EL CUBANO Ham, pork, sweet pickles, swiss cheese, dijon mustard 17 Desserts FLAN DE VANILLA Cuban-style custard 9 COHO Y CORTADITO Wafer cookie, nutella, fondant espresso milk shake 12 Consuming raw or undercooked meats, poultry, seafood, shellfish, or eggs may increase your risk of foodborne illness, especially if you have certain medical conditions. Cocktails CUBAN CAFE MARTINI Vodka, Cuban Espresso, Fernet Branca 13 CUBA LIBRE Light Rum, Falernum, Lime, Original Cola 12 HAVANA PUNCH Dark Rum, Light Rum,Fresh Juices, Cinnamon Honey, Ginger Beer (Serves up to Four) 24 CANCHÁNCHARA “The Original Cuban Cocktail” Light Rum, Lime, Honey 10 LOST ON THE ISLAND Rye Whiskey, Demerara Syrup, Banana Liqueur, Aromatic Bitters 12 Beers AGUILA ORGINAL CERVEZA American Style Lager, Bogota Colombia 5 MADURO BROWN ALE Brown Ale, Tampa Bay, Florida 5 FLORIDA CRACKER Witbier, Tampa Bay, Florida 5 INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ALE American IPA, Bradenton, Florida 5 PULP FRICTION American IPA, Bradenton, Florida 5 Wines MARQUÉS DE VIZHOJA Albariño, Galicia, Spain 12/47 BODEGA NORTON BARREL SELECT Sauvignon Blanc, Mendoza, Argentina 10/39 BODEGAS SALENTEIN Chardonnay, Mendoza, Argentina 9/35 MONTES ALPHA Carménère, Central Valley, Chile 14/55 ALTA VISTA VIVE Malbec, Mendoza, Argentina 10/39 1895 BY BODEGA NORTON Cabernet Sauvignon, Mendoza, Argentina 10/39 Please ask your server for full wine list. -

QUARTERLY Theme of the Issue

Les Dames d’Escoffier International QUARTERLY Theme of the Issue: Dame Food Stylists and Photographers LDEI on-line Auction Dallas Chapter History Award Winning Dames LDEI Directory Changes Food Verse Seattle, Atlanta, Chicago, Hawaii, Miami Dallas Chapter Programs San Antonio Annual Conference Update MFK Fisher Luncheon Speaker US State Department Assistant Chief of Protocol Adelaide, Australia · Atlanta · Boston · British Columbia · Chicago · Dallas Honolulu · Houston · Kansas City · Le Donne del Vino, Italy · Los Angeles Miami · Minneapolis/St. Paul · New York · Palm Springs · Philadelphia Phoenix · San Antonio · San Francisco · Seattle · Washington, D.C. SUMMER 2002 Les Dames d’Escoffier International 2001-2002 President’s Message OFFICERS There are no greater It is extremely gratifying to be President proponents of the pleasures of an officer on the executive Renie Steves food, wine, and hospitality in committee. LYNN FREDERICKS is 1406 Thomas Place the world than Dames. And giving you a fabulous website Ft. Worth, TX 76107-2432 possibly, no busier women! So in July. KATHERINE NEWELL (817) 732-4758 why make time to volunteer SMITH collects and edits news [email protected] for Les Dames activities? for the Quarterly, while CICI WILLIAMSON Foremost, our Les Dames tenaciously network really works—locally searches for partners to help First VP/Pres. Elect us further LDEI’s mission. CiCi Williamson and internationally. A Dame LDEI president ABBY MANDEL, our “new 6025 Chesterbrook Road from another chapter recommended Miami Dame Renie Steves territory” officer, works to form McLean, VA 22101-3213 new chapters. Pat Mozersky is VIRGINIA FLORES DE APODACA for a job [email protected] streamlining the annual process of conducting research for community creating our membership directory. -

The Cuban Full Menu

MENU THE CUBAN FOOD S T O R Y Cuba is a fascinating country with an even more fascinating history, which has had a great influence over the food and cooking styles. In the glamorous 1950’s Cuba was an exotic playground with fine food in abundance. Celebrities would flock to Havana for the up-market bars and restaurants. In Cuba today you would find a simple yet very effective style of food and cooking. Cuban cuisine has also been influenced by Spanish, French, African, Arabic, Chinese and Portuguese cultures, which makes it just that little more interesting. We welcome you to The Cuban, we wish you a very enjoyable experience. GRAND HAVANA BANQUET $65pp or $60pp without dessert PAN TIBIO Bread and house made Spanish dips DULCE CERDO PICANTE Slow cooked pork belly finished with a glaze of honey and chilli paired with apple and cinnamon HAVANOS CUBANOS Spiced lamb Cuban cigars with minted yoghurt PARMESAN MASH CROCANTE CALAMARI Crispy salt and pepper calamari GAMBAS AL AJILLO Pan fried prawns with garlic and chilli cream, black bean rice SWEETCORN & BLACK BEAN RICE ROPA VIEJA Shredded beef, sweetcorn and black bean rice, tostone PAELLA CUBANA Chicken, chorizo, prawns, calamari tossed with saffron rice, sweetcorn and black beans STEAMED SEASONAL VEGETABLES SPANISH CHURROS Served with liquid dark chocolate and Bailey’s infused cream Vegetarian menu options are available upon request Minimum 4 pax VARADERO BANQUET $40pp PAN TIBIO Bread and house made Spanish dips DULCE CERDO PICANTE Slow cooked pork belly finished with a glaze of honey and -

A Guide to Tourism Careers, Education and Training in the Caribbean

A Guide to Tourism Careers, Education and Training in the Caribbean Compiled by: Shirlene A. Nibbs, Antigua, W.I. Nibbs & Associates, with assistance from Bonita Morgan, Director of Human Resources, CTO Edited by: Bonita Morgan Director of Human Resources, CTO Published by: Caribbean Tourism Organization 2nd Floor, Sir Frank Walcott Building Culloden Farm Complex, St Michael Barbados, West Indies Phone: (246) 427-5242 Fax:(246) 429-3065 E-mail address: [email protected] Website address:http//www.caribtourism.com Designed & Produced by: Devin Griffith #195 Frere Pilgrim, Christ Church, Barbados Tel: 437-4030 E-mail address: [email protected] Printed by: Caribbean Graphics, Wildey, St. Michael, Barbados Tel: (246)-431-4300 Fax: (246)-429-5425 Date: April 1999 AA Guide to Tourism Careers, Education and Training inin thethe CaribbeanCaribbean 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ........................................................................................................... 4 PART I: AN OVERVIEW OF CARIBBEAN TOURISM .................................... 5 The International Scene .................................................................. 6 The Caribbean .................................................................................. 6 One of the Premier Warm Weather Destinations .......................... 10 Strong Growth in Other Markets .................................................... 11 Geographic, Cultural and Ethnic Diversity .................................... 12 ‘Know Your Region’ Quick Quiz .................................................. -

Nycfoodinspectionsimple Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results

NYCFoodInspectionSimple Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results DBA BORO STREET ZIPCODE ZUCCHERO E POMODORI Manhattan 2 AVENUE 10021 BAGEL MILL Manhattan 1 AVENUE 10128 MERRYLAND BUFFET Bronx ELM PLACE 10458 NI-NA-AB RESTAURANT Queens PARSONS BOULEVARD KFC Queens QUEENS BLVD 11373 QUAD CINEMA, QUAD Manhattan WEST 13 STREET 10011 BAR JADE GARDEN Bronx WESTCHESTER AVENUE 10461 EL VALLE RESTAURANT Bronx WESTCHESTER AVENUE 10459 EL VALLE RESTAURANT Bronx WESTCHESTER AVENUE 10459 CHIRPING CHICKEN Bronx BUHRE AVENUE 10461 UNION HOTPOT, SHI Brooklyn 50 STREET 11220 SHANG SAINTS AND SINNERS Queens ROOSEVELT AVE 11377 SAINTS AND SINNERS Queens ROOSEVELT AVE 11377 HAPPY GARDEN Brooklyn 3 AVENUE 11209 MUGHLAI INDIAN CUISINE Manhattan 2 AVENUE 10128 PAQUITO'S Manhattan 1 AVENUE 10003 CAS' WEST INDIAN & Brooklyn KINGSTON AVENUE 11213 AMERICAN RESTAURANT BURGER INC Manhattan WEST 14 STREET 10014 Page 1 of 556 09/28/2021 NYCFoodInspectionSimple Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results CUISINE DESCRIPTION INSPECTION DATE Italian 10/31/2019 Bagels/Pretzels 02/28/2020 Chinese 04/22/2019 Latin American 04/09/2018 American 09/09/2019 American 07/27/2018 Chinese 08/02/2021 Latin American 06/14/2017 Latin American 06/14/2017 Chicken 04/11/2018 Chinese 07/25/2019 American 05/06/2019 American 05/06/2019 Chinese 05/02/2018 Indian 10/11/2017 Mexican 04/04/2017 Caribbean 11/16/2017 American 08/27/2018 Page 2 of 556 09/28/2021 NYCFoodInspectionSimple Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results LA CABANA Manhattan -

Than 230 Ideas About Your Future

FOOD TRE NDS 2017MORE THAN 230 IDEAS ABOUT YOUR FUTURE www.sysco.com Chefs Predict “What’s Hot” for Menu Trends in 2 017 www.restaurant.org Dec. 8, 2016 Each year, the National Restaurant Association surveys nearly 1,300 professional chefs – members of the American Culinary Federation (ACF) – to explore food and beverage trends at restaurants in the coming year. The annual “What’s Hot” list gives a peak into which food, beverages and culinary themes will be the new items on restaurant menus that everyone is talking about in the year ahead. According to the survey, menu trends that will be heating up in 2017 include poke, house-made charcuterie, street food, food halls and ramen. Trends that are cooling down include quinoa, black rice, and vegetarian and vegan cuisines. TOP 20 FOOD TRENDS TOp 10 concept trends “Menu trends today are beginning to shift from ingredient-based items to concept-based ideas, mirroring how consumers tend to adapt their activities to their overall lifestyle philosophies, such as environmental sustainability and nutrition,” said Hudson Riehle, Senior Vice President of Research for the National Restaurant Association. “Also among the top trends for 2017, we’re seeing several examples of house-made food items and various global flavors, indicating that chefs and restaurateurs are further experimenting with from-scratch preparation and a broad base of flavors.” The National Restaurant Association surveyed 1,298 American Culinary Federation members in October 2016, asking them to rate 169 items as a “hot trend,” “yesterday’s news,” or “perennial favorite” on menus in 2017. -

Cigar Lover's Cuba HAVANA � PINAR DEL RIO � VIÑALES Cuba Has a Rich History and Culture and Is Known for Being an Artistic and Welcoming Destination

code color cymk C: 0% M:26% Y:70% K:0% C: 80% M:69% Y:0% K:40% 6 DAYS� 5 NIGHTS Cigar Lover's Cuba HAVANA � PINAR DEL RIO � VIÑALES Cuba has a rich history and culture and is known for being an artistic and welcoming destination. This tour showcases all that makes up Cuba, including a focus on one of its prized national products: tobacco. On this Cigar Lover’s program experience everything from the rich tobacco fields to the factories where each cigar is still rolled and made by hand! You’ll go home with a better appreciation for this Cuban favorite! Your Itinerary Day 1 • Arrival in Havana International Airport, transfer to the hotel. • Brief meeting with the Tour Guide and driver to go over the program. • Panoramic tour of Havana, where you will see some of the city’s emblematic places, like the 18th century University, one of America’s oldest; the inviting Malecón; the time witnessed Paseo del Prado and the eye- catching Capitol. There will be a stop to take pictures at the Revolution Square. • Lunch at a local paladar, with time to interact with the owner and staff over their Cuban cuisine. • Visit to the art studio of Cuban painter Jose Fúster, to learn about his work and the importance of his community Project. • Check in at the hotel. • American antique car ride towards the restaurant. The drivers will proudly and gladly answer your questions on how they keep these rolling museum pieces up and running and in such good shape! • Welcome dinner at a local restaurant, including a classic Daiquirí cocktail. -

VARADERO BANQUET 65Pp–Min

GRAND HAVANA BANQUET VARADERO BANQUET 65pp–Min. 4 pax 45pp–Min. 2 pax PAN CON TOMATO PAN CON TOMATO Grilled baguette bread, tomato coulis infused Grilled baguette bread, tomato coulis infused with garlic, Aged Serrano Jamon with garlic, Aged Serrano Jamon TORTILLA DE PATATA TORTILLA DE PATATA Classic Spanish potato and onion omelet, Classic Spanish potato and onion omelet, capsicum and tomato sauce capsicum and tomato sauce CHORIZO CHORIZO THE CUBAN FOOD STORY Authentic Spanish chorizo cooked in sweet Authentic Spanish chorizo cooked in sweet and sour sauce, baguette toasts, rocket salad and sour sauce, baguette toasts, rocket salad Cuba is a fascinating country with an even more fascinating history, which has had a CALAMARES A LA ROMANA CALAMARES A LA ROMANA great influence over the food and cooking Lemon battered fried calamari Lemon battered fried calamari styles. In the glamorous 1950’s Cuba was an with harissa mayonnaise with harissa mayonnaise exotic playground with fine food in abundance. Celebrities would flock to Havana for the CUBAN CHICKEN SKEWERS PAELLA CUBANA up-market bars and restaurants. Marinated free range tenderloin chicken skewers, Traditional Cuban paella with chicken, Spanish chorizo, rocket, pear, walnuts, fig salad with goats cheese, prawns, mussels, calamari and saffron rice In Cuba today you would find a simple yet honey and mustard dressing very effective style of food and cooking. Cuban cuisine has also been influenced by SPANISH CHURROS Spanish, French, African, Arabic, Chinese and SETAS Dark chocolate sauce and Baileys infused cream Portuguese cultures, which makes it just that Pan fried buttons mushrooms with parsley and garlic butter little more interesting. -

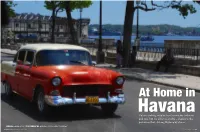

Cuban Cooking May Be Best Known for Its Beans and Rice, but It's All Set To

Cuban cooking may be best known for its beans and rice, but it’s all set to evolve – thanks to the paladares that’s taking Havana by storm. WORDS ESME FOX | PHOTOGRAPHS ESME FOX & DAN CONVEY 54 | WildJunket August/September 2012 www.wildjunket.com | 55 FEAST CUBA FEAST CUBA Colors of Cuba: the famous Havana Club t’s nearly nightfall in Old Havana and my stomach is The Warmth of Home growling, but when I look at the address of La Mulata Paladares began in opposition to the Cuban government, del Sabor – “!e Taste of La Mulata” in Spanish, this when people set up secret restaurants inside their homes surely can’t be right. during the post-Soviet economic crisis in the 1990s. !is isn’t a restaurant; it is someone’s home. ! !ey were legalized soon a$er and are now all the rage I knock quietly, hesitantly. !e clatter of plates and faint in Havana, bringing new light to its normally lackluster strains of music stream onto the street. When the rickety dining scene. door swings open, I instantly know that I’ve come to the Many have established themselves as gourmet right place. restaurants, some are sticking to tradition, dishing up good I’m greeted by La Mulata herself – a gregarious Cuban ol’ Creole home cooking, while others are coming up with woman with cocoa-colored skin, chestnut brown curls, new-age dishes like fried bananas stu%ed with cheese and and thick lips painted bright red like rubies. She invites me pork medallions with mango glaze. -

Herskovits and the Problem of Induction, Or, Guinea Coast, 1593 In

B. Maurer Fact and fetish in creolization studies: Herskovits and the problem of induction, or, Guinea Coast, 1593 In: New West Indian Guide/ Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 76 (2002), no: 1/2, Leiden, 5-22 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl BILL MAURER FACT AND FETISH IN CREOLIZATION STUDIES: HERSKOVITS AND THE PROBLEM OF INDUCTION, OR, GUINEA COAST, 1593 Two things strike me in reading some of the work cited by Richard Price (2001) in his retrospective on creolization in the African diaspora in the Americas.' First, although Melville Herskovits's research on New World Africanity figures prominently either as source of inspiration, object of criticism, or merely useful signpost, his equally influential writings on economie anthropology and their possible relation to his work on African survivals in the New World are largely absent from the discussion.2 Second, in a debate oriented largely around differ- ing interpretations of "much the same data" (R. Price 2001:52), and in which attention to "what went on in specifie places and times" (Trouillot 1998:20) is paramount, there is little reflection on the status of the facts asfacts and the modality of inductive reasoning in which historical particularism makes sense. In the case of African survivals, the problem of induction is particularly acute since the data that might be admitted as evidence are rarely straightforwardly evident to the senses.3 1. I would like to thank Jennifer Heung, Rosemarijn Hoefte, Tom Boellstorff, Kevin Yelvington, and the reviewers for the NWIG for their comments, criticisms, suggestions (and photocopies!) of some sources, as well as their general collegial assistance. -

Old Neighborhood, New Look Allapattah Is Changing – Fast

May 2019 www.BiscayneTimes.com Volume 17 Issue 3 © Old Neighborhood, New Look Allapattah is changing – fast CALL 305-756-6200 FOR INFORMATION ABOUT THIS ADVERTISING SPACE 2 Biscayne Times • www.BiscayneTimes.com May 2019 TASTE OF TURNBERRY Join us for Local Eats & Crafted by CORSAIR, which pair our award- winning chefs with some of Miami’s most noteworthy chefs & brewmasters. Located at JW Marriott Miami Turnberry Resort & Spa. FIND OUT MORE AT JWTURNBERRY.COM/EVENTS Crafted by CORSAIR Four-course dinners Local Eats paired with local brews Five-course dinners paired with wines and spirits May 30 Due South Brewing Co. June 12 August 29 Executive Chef Steve Santana June 27 Biscayne Bay Brewing Co. Taquiza, Miami Beach J. Wakefield Brewing July 17 September 26 July 25 Executive Chef Justin Flint Concrete Beach Brewery Cigar City Brewing Alter, Miami May 2019 Biscayne Times • www.BiscayneTimes.com 3 Where Buyers 2019 New 5,300 SF Waterfront Home 160 ft of New Seawall ! and Sellers ` intersect every day 13255 Keystone Terrace - $1.650M Rare opportunity to find a 160 ft waterfront home with 2019 New Waterfront Pool Home - $2.49M new seawall just steps to the Bay! For sale at lot New 5,300 SF Contemporary Home with Ocean Access, no value. 160' ft on water with no bridges to Bay… Remodel bridges to Bay. 4BR, 5BA + den/office or 5th BR, 665sf this 5BR 4,589 sf home with your personal touches or covered patio downstairs. 2 car gar. Dock up to 75' ft boat. build your waterfront dream home on 13,000 sf lot.