Looking for Locsin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Churches of Leandro V. Locsin in the Philippines

DOCUMENTATION ISSUES subject to humidity, have not only moulded the development of architecture, but also have limited our knowledge of its history by leaving little if no vestiges of the past.6 Religious Tropical Architecture: the churches He thus put forward an approach, for him of Leandro V. Locsin in the Philippines fundamental, which had previously tended to be ignored. Church renewal BY JEAN-CLAUDE GIRARD in the aftermath of WWII At the beginning of the Spanish period, existing buildings were repurposed and The focus of this contribution is on the importance of tropical architecture in the work of Leandro enlarged, in order to provide sufficient space V. Locsin, in the context of post-WWII in Asia. Based in the Philippines, Locsin is immersed in the for the gathering of the faithful. However, the Christian tradition – the main religion of a country that was dominated by the Spanish crown from successive destruction caused by typhoons the mid 16th-century to 1898, and where the Catholic Church remains powerful across much of and earthquakes leads to the re-evaluation of the construction method. Church structures, the archipelago today. Attention is focused on Locsin’s religious buildings and projects, where he still arranged on a basilica plan, were built succeeded in giving a new treatment to the tropical architecture of faith-based structures, through of stone and stabilized by lateral buttresses. the integration of climate considerations and the reinterpretation of vernacular architecture of the If the plan reflected a form of organization Philippines. imposed by the Eucharist, the profile was stockier, and the bell tower separated, in order to resist telluric movements.7 After independence in 1946 new religious Leandro V. -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman -

FRISSON: the Collected Criticism of Alice Guillermo

FRIS SON: The Collected Criticism of Alice Guillermo Reviewing Current Art | 23 The Social Form of Art | 4 Patrick D. Flores Abstract and/or Figurative: A Wrong Choice | 9 SON: Assessing Alice G. Guillermo a Corpus | 115 Annotating Alice: A Biography from Her Bibliography | 16 Roberto G. Paulino Rendering Culture Political | 161 Timeline | 237 Acknowledgment | 241 Biographies | 242 PCAN | 243 Broadening the Public Sphere of Art | 191 FRISSON The Social Form of Art by Patrick D. Flores The criticism of Alice Guillermo presents an instance in which the encounter of the work of art resists a series of possible alienations even as it profoundly acknowledges the integrity of distinct form. The critic in this situation attentively dwells on the material of this form so that she may be able to explicate the ecology and the sociality without which it cannot concretize. The work of art, therefore, becomes the work of the world, extensively and deeply conceived. Such present-ness is vital as the critic faces the work in the world and tries to ramify that world beyond what is before her. This is one alienation that is calibrated. The work of art transpiring in the world becomes the work of the critic who lets it matter in language, freights it and leavens it with presence so that human potential unerringly turns plastic, or better still, animate: Against the cold stone, tomblike and silent, are the living glances, supplicating, questioning, challenging, or speaking—the eyes quick with feeling or the movements of thought, the mouths delicately shaping speech, the expressive gestures, and the bodies in their postures determined by the conditions of work and social circumstance. -

The City As Illusion and Promise

Ateneo de Manila University Archīum Ateneo Philosophy Department Faculty Publications Philosophy Department 10-2019 The City as Illusion and Promise Remmon E. Barbaza Follow this and additional works at: https://archium.ateneo.edu/philo-faculty-pubs Part of the Other Philosophy Commons Making Sense of the City Making Sense of the City REMMON E. BARBAZA Editor Ateneo de Manila University Press Ateneo de Manila University Press Bellarmine Hall, ADMU Campus Contents Loyola Heights, Katipunan Avenue Quezon City, Philippines Tel.: (632) 426-59-84 / Fax (632) 426-59-09 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ateneopress.org © 2019 by Ateneo de Manila University and Remmon E. Barbaza Copyright for each essay remains with the individual authors. Preface vii Cover design by Jan-Daniel S. Belmonte Remmon E. Barbaza Cover photograph by Remmon E. Barbaza Book design by Paolo Tiausas Great Transformations 1 The Political Economy of City-Building Megaprojects All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, in the Manila Peri-urban Periphery stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or Jerik Cruz otherwise, without the written permission of the Publisher. Struggling for Public Spaces 41 The Political Significance of Manila’s The National Library of the Philippines CIP Data Segregated Urban Landscape Recommended entry: Lukas Kaelin Making sense of the city : public spaces in the Philippines / Sacral Spaces Between Skyscrapers 69 Remmon E. Barbaza, editor. -- Quezon City : Ateneo de Manila University Press, [2019], c2019. Fernando N. Zialcita pages ; cm Cleaning the Capital 95 ISBN 978-971-550-911-4 The Campaign against Cabarets and Cockpits in the Prewar Greater Manila Area 1. -

Gender As the Elephant in the Room of Southeast Asian Art Histories

Art on the Back Burner: Gender as the Elephant in the Room of Southeast Asian Art Histories Eileen Legaspi-Ramirez Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, Volume 3, Number 1, March 2019, pp. 25-48 (Article) Published by NUS Press Pte Ltd DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/sen.2019.0002 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/721044 [ Access provided at 23 Sep 2021 11:07 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] Art on the Back Burner: Gender as the Elephant in the Room of Southeast Asian Art Histories EILEEN LEGASPI-RAMIREZ Abstract Despite the operative skepticism about the way compensatory art history appears to have reduced the feminist project to merely expanding rather than challenging the canon, the assertion here is that still too scant attention has been paid to studying the critical role that primarily woman artist-organisers have played in shaping narratives of practice. In focusing on their visible tasks through variable degrees of sublimating art practice in deference to less visible tasks like archiving, art education, organising and publication, the research also privileges the aspects of circulation and reception as it revisits the shaping of artworlds in stories that have ironically kept such ‘maintenance’ tasks virtually off the record. It is telling that certain visual correlatives for the woman in Southeast Asia continue to circulate: from Garuda’s wing in Indonesia to an elephant’s hind legs in Thailand, we find amidst these variably poetic depictions an emplacing that literally decentres women from the pivotal junctures of action. -

History of Philippine Architecture ARCHITECT MANUEL D

History of Philippine Architecture ARCHITECT MANUEL D. C. NOCHE The history and culture of the Philippines are reflected in its architectural heritage, in the dwellings of its various peoples, in churches and mosques, and in the buildings that have risen in response to the demands of progress and the aspirations of the people. Architecture in the Philippines today is the result of a natural growth enriched with the absorption of varied influences. It developed from the pre-colonial influences of our neighboring Malay brothers, continuing on to the Spanish colonial period, the American Commonwealth period, and the modern contemporary times. As a result, the Philippines has become an architectural melting pot-- uniquely Filipino with a tinge of the occidental. The late national hero for architecture, Leandro Locsin once said, that Philippine Architecture is an elusive thing, because while it makes full use of modern technology, it is a residue of the different overlays of foreign influences left in the Philippines over the centuries: the early Malay culture and vestiges of earlier Hindu influences, the more than 300 years of Spanish domination, the almost 50 years of American rule, the Arab and Chinese influences through commerce and trade over the centuries. What resulted may have been a hybrid, a totally new configuration which may include a remembrance of the past, but transformed or framed in terms of its significance today. The Philippine's architectural landscape is a contrast among small traditional huts built of wood, bamboo, nipa, grass, and other native materials; the massive Spanish colonial churches, convents and fortifications, with their heavy "earthquake baroque" style; the American mission style architecture as well as the buildings of commerce with their modern 20th century styles; and today's contemporary, albeit "modern mundane" concrete structures of the cities. -

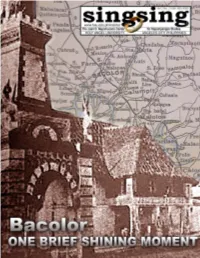

Real Bacolor-Layout

www.hau.edu.ph/kcenter The Juan D. Nepomuceno Center for Kapampangan Studies HOLY ANGEL UNIVERSITY ANGELES CITY, PHILIPPINES 1 RECENTRECENT VISITORS MARCH & APRIL F. Sionil Jose Ophelia Dimalanta Mayor Ding Anunciacion, Bamban, Mayor Genaro Mendoza, Tarlac City Joey Lina Sylvia Ordoñez Mayor Carmelo Lazatin, Angeles Vice Mayor Bajun Lacap, Masantol Ely Narciso, Kuliat Foundation Ching Escaler Maribel Ongpin Gringo Honasan Crisostomo Garbo Museum Foundation of the Philippines M A Y Kayakking among the mangroves in Masantol Dennis Dizon Senator Tessie Aquino Oreta Mikey Arroyo Mayor Mary Jane Ortega, San Fernando City, La Union Cecilia Leung River tours launched Ariel Arcillas, Pres, SK Natl Federation THE Center sponsored a multi-sector Congressman Bondoc promised to Mark Alvin Diaz, SK Nueva Ecija Tessie Dennis Felarca, SK Zambales research cruise down Pampanga River convert a portion of his fishponds into a Oreta Brayant Gonzales, Angeles City last summer, discovered that the river is mangroves nursery and to construct a port Council not as silted and polluted as many believe, in San Luis town where tourist boats can Vice Mayor Pete Yabut, Macabebe and as a result, organized cultural and dock. The town’s centuries-old church is Vice Mayor Emilio Capati, Guagua ecological tours in coordination with the part of the planned itinerary for church Carmen Linda Atayde, SM Department of Tourism Region 3, local gov- heritage river cruises. Other cruise options Foundation ernment units in the river communities, include a tour of the mangroves in Masantol Efren de la Cruz, ABC President Estelito Mendoza and a private boatyard owner. and Macabebe, and tours coinciding with Col. -

Ji:J L:., .,~· .•:·····-M· '...:J • ··~ ..I ·- •

•• .... , •, • '.~~:!~I _;,:. ' •. • ·L..:·,·• ' • ,.j \·: ...... : ,..,.~):,:r ·t1~:"~~ ~-~rt.." .. f ·-. :- ... • • .~ ..\~,·~-.-~. \"'--il:.. ~........ --•. , " · ~:.: fl', !"1 r~· i l' ;I) 1"11 • •, \ l' j \ '.;"J'-u~w-~•4 < J. ••] l ! I\ i' · ! ' ! I; I ~ fi\ !i NOV 1o 2316 ) ! i I ,ji:J l:., .,~· .•:·····-m· '...:J • ··~ ..I ·- • ....... " e.,;.,. ~ .... !..:./ i'• ·~. ·-"·--· --·--- • -: .. ~.• '.~-· ..:..11a..pbl--- ~epublic of tbe ~bilippine£i $upreme <!Court ;iflllanila EN BANC SATURNINO C. OCAMPO, TRINIDAD G.R. No. 225973 H. REPUNO, BIENVENIDO LUMBERA, BONIFACIO P. ILAGAN, NERI JAVIER COLMENARES, MARIA CAROLINA P. ARAULLO, M.D., SAMAHAN NG EX DETAINEES LABAN SA DETENSYON AT ARESTO (SELDA), represented by DIONITO CABILLAS, CARMENCITA M. FLORENTINO, RODOLFO DEL ROSARIO, FELIX C. DALISAY, and . * DANILO M. DELA FUENTE, Petitioners, - versus - REAR ADMIRAL ERNESTO c. ENRIQUEZ (in his capacity as the Deputy Chief of Staff for Reservist and Retiree Affairs, Armed Forces of the Philippines), The Grave Services Unit (Philippine Army), and GENERAL RICARDO R. VISAYA (in his capacity as the Chief of Staff, Armed Forces of the Philippines), DEFENSE SECRETARY DELFIN LORENZANA, and HEIRS OF FERDINAND E. MARCOS, represented by his surviving spouse Imelda Romualdez Marcos, Respondents. x --------------------------------------------------- x Rene A. V. Saguisag, et al. filed a petition for certiorari-in-intervention. r/ Decision 2 G.R. No. 225973, 225984, 226097, 226116, 226117, 226120, & 226294 RENE A.V. SAGUISAG, SR., RENE A.Q. SAGUISAG, JR., RENE A.C. SAGUISAG III, Intervenors. x --------------------------------------------------- x REP. EDCEL C. LAGMAN, in his G.R. No. 225984 personal and official capacities and as a member of Congress and as the Honorary Chairperson of the Families of Victims of Involuntary Disappearance (FIND); FAMILIES OF VICTIMS OF INVOLUNTARY DISAPPEARANCE (FIND), represented by its Co Chairperson, NILDA L. -

DOSSIER PHILIPPINE ARCHITECTURE in the VENICE BIENNALE CURATORIAL TEAM Leandro V. Locsin Partners LEANDRO V. LOCSIN PARTNERS Is

DOSSIER PHILIPPINE ARCHITECTURE in the VENICE BIENNALE CURATORIAL TEAM Leandro V. Locsin Partners LEANDRO V. LOCSIN PARTNERS is the current incarnation of an unbroken and continuing architectural practice founded in 1955 by Leandro V. Locsin (+), Philippine National Artist for Architecture. The firm is credited with having helped shape Manila’s skyline and architectural landscapes. One of its earliest commissions, a high rise apartment building on Ayala Avenue, set the architectural idiom for subsequent buildings on what was then the frontier of urban development and what has become Manila’s premier business district. The firm’s influence goes well beyond Ayala Avenue. From its drawing boards have sprung notable work such as the Chapel of the Holy Sacrifice at the University of the Philippines, the Cultural Center of the Philippines Complex, the 1970 Philippine Pavilion in Osaka, the Philippine International Convention Center, the Manila Hotel Redevelopment, the Mandarin Oriental Hotel, the Manila International Airport, The first Citibank Building, the Makati and Philippine Stock Exchanges, the Anvaya Cove Resort Community, and the Ayala Museum (old and new). Since 1955 the firm has designed over 33 public buildings, 75 commercial buildings, 6 hotels, 13 churches, several country clubs and museums, and more than 100 residences in the country's most exclusive communities. The firm's most comprehensive project to date is the New Istana Nurul Iman State Palace and Seat of Government for the Sultan of Brunei in Bandar Seri Begawan. Encompassing a total floor area of approximately 200,000 square meters, the palace has the distinction of being the world's largest presidential residence.1 Leandro Locsin, Jr. -

Annual Report 2009

Philippine Social Science Council ...a private organization of professional social science associations in the Philip- pines Annual Report 2009 1 2 Table of Contents Proposed Agenda 5 Minutes of the 2009 Annual General Membership Meeting 7 Chairperson's Report 13 Treasurer's Report 21 Accomplishment Reports Regular Members 41 Associate Members 81 Board of Trustees Resolutions 187 Directory of PSSC Members 189 Regular Members Associate Members 3 4 PSSC Annual General Assembly 20 February 2010, 12:30 p.m. Proposed Agenda I. Call of the meeting to order II. Proof of quorum III. Approval of the proposed agenda IV. Approval of the minutes of the 2009 Annual General Assembly V. Business arising from the minutes of the previous meeting VI. New business a. Chairperson’s report b. Treasurer’s report c. Membership Committee report d. Announcements and other matters VII. Adjournment 5 6 Minutes of the Annual General Assembly PSSC Auditorium 21 February 2009, 9:00 a.m. ATTENDANCE Regular Members Linguistic Society of the Philippines Isabel Martin Danilo Dayag Philippine Association of Social Workers Inc. Augosto Tordillos Feli Sustento Joy Pontenila Philippines Communication Society Lourdes Portus Philippine Economic Society Winfred Villamil Fernando Aldaba Philippine Geographical Society Doracie Nantes Trina Isorena Philippine Historical Association Evelyn Songco Gloria Santos Philippine National Historical Society Digna Apilado Violeta Ignacio Philippine Political Science Association Maria Ela Atienza Ruth Rico Philippine Population Association Nimfa Ogena Philippine Society for Public Administration Wilhelmina Cabo Philippine Sociological Society Manuel Diaz Filomin Gutierrez Manny de Guzman Philippine Statistical Association Lisa Grace Bersales Psychological Association of the Philippines Allan Bernardo Lucila Bance Ugnayang Pang-Aghamtao, Inc. -

The Cultural Heritage-Oriented Approach to Economic

Arts and Culture: Heritage, Practices and Futures Presented at the 10th DLSU Arts Congress De La Salle University Manila, Philippines February 16, 2017 De La Salle University, Manila, Philippines The Cultural Heritage-Oriented Approach to Economic Development in the Philippines: A Comparative Study of Vigan, Ilocos Sur and Escolta, Manila Geoffrey Rhoel Cruz [email protected] Mapua Institute of Technology Manila, The Philippines Abstract: Goal 11 of the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals prescribes that culture matters. However, the case of Escolta, Manila presents otherwise. This paper investigates the ways how cultural heritage can be a driver for economic development in the Philippines following the Van Der Borg and Russo’s (2005) Culture-Oriented Economic Development (COED) framework. It stresses the interrelationship of inner cultural cluster dynamics, economic impacts, and socio-environmental impacts which provides for a cycle composed of culture promoting development and in return development fostering culture, then leading to development. The case of Escolta, Manila was compared to the case of Vigan, Ilocos Sur using the one-off initiative framework provided by UNESCO World Heritage Centre for heritage conservation. The results revealed that it is the lack of interest of property owners in Escolta, Manila as the principal shareholders that makes built-heritage conservation unmanageable. Since most built heritages are privately owned and have not been granted heritage status by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP), efforts to revive Escolta face significant threats. Thus there is a need for concrete legislative frameworks to address such apathy. Interestingly, the results corroborated the findings of Palaña (2015) explaining why it is easy for owners to sell the property or leave it to deteriorate than be burdened by its preservation costs without any definite return of investment. -

Filipino Pride, Is a Timely “It Is a Brilliant and Patriotic Initiative, Piece of Truth

“There are so many things that we can be proud of about our country... …we just have to know them.” www.FilipinoMatters.org “... This book, The Filipino Pride, is a timely “It is a brilliant and patriotic initiative, piece of truth. It serves as a reminder of it highlights the many positive qualities our country’s pride. It reminds us of a and accomplishments of Filipinos. I would number of reasons why we should never commend this book especially to Pinoys stop surviving and succeeding as Filipinos abroad.” who will always be proud of our country.” - Bernardo Villegas - Joey Concepcion Economics Professor Presidential Consultant for University of Asia and Pacific Entrepreneurship and Founding Trustee, Philippine Center For Entrepreneurship “This is a brilliant piece of project illuminating the totality of our past and “You are a Filipino if you are proud to be present Filipino culture and achievements. one! This is the message of this book ... This work is an effective tool aimed at Not everyone nor everything that makes emancipating the confused minds and Filipinos models for citizens of other feelings of our own youth including countries is in this book, but this is a giant second and third generations of Filipinos step towards restoring Filipino pride...” living abroad whose denial and confusion from knowing their very own root can be - Isagani Cruz substituted with pride and a strong sense Playwright, short-story writer, writing of connectivity to our Filipino nation. I critic, educator, columnist and publisher therefore commend contributors for this valuable project they have done.” “We all need to be reminded once in a while why we should be proud to be Filipino.