Outer Space Lessons for Earthside Safety

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Area 51 and Gordon Coopers Confiscated Camera

Area 51 and Gordon Cooper's 'Confiscated Camera' By Jim Oberg Special to SPACE.com posted: 11:34 am ET 29 September 2000 http://www.space.com/sciencefiction/phenomena/cooper_questioned_000929.html Mercury astronaut Gordon Cooper, in his new book Leap of Faith, presents a tale of government cover-ups related to spy cameras, to Area 51, and to similar subjects top-secret subjects, based on his own personal experiences on a NASA space mission. As a certified "American hero," his credibility with the public is impeccable. But several space veterans who SPACE.com consulted about one of Cooper's spaceflight stories had very different versions of the original events. And some of them showed me hard evidence to back up their skepticism. According to Cooper, in 1965 he carried a super-secret spy camera aboard Gemini-5 and accidentally got some shots of Area 51 in Nevada. Consequently, the camera and its film were confiscated by the Pentagon, never to be seen again. He was personally ordered by President Johnson not to divulge the film's contents. "One special mounted camera we carried had a huge telephoto lens," he wrote. "We were asked to shoot three specific targets from our spacecraft's window because the photo experts wanted to be able to measure the resolution of the pictures. "That's exactly what we did: Over Cuba, we took pictures of an airfield. Over the Pacific Ocean, we took pictures of ships at sea. Over a big U.S. city, we took pictures of cars in parking lots. Beyond that, we were encouraged to shoot away at other airfields, cities, and anything else we wanted along the way." In an exclusive interview with SPACE.com, NASA's former chief photo analyst, Richard Underwood, confirmed the existence of the experiment but remembered details about it in a very different way than Cooper did. -

Appendix a Apollo 15: “The Problem We Brought Back from the Moon”

Appendix A Apollo 15: “The Problem We Brought Back From the Moon” Postal Covers Carried on Apollo 151 Among the best known collectables from the Apollo Era are the covers flown onboard the Apollo 15 mission in 1971, mainly because of what the mission’s Lunar Module Pilot, Jim Irwin, called “the problem we brought back from the Moon.” [1] The crew of Apollo 15 carried out one of the most complete scientific explorations of the Moon and accomplished several firsts, including the first lunar roving vehicle that was operated on the Moon to extend the range of exploration. Some 81 kilograms (180 pounds) of lunar surface samples were returned for anal- ysis, and a battery of very productive lunar surface and orbital experiments were conducted, including the first EVA in deep space. [2] Yet the Apollo 15 crew are best remembered for carrying envelopes to the Moon, and the mission is remem- bered for the “great postal caper.” [3] As noted in Chapter 7, Apollo 15 was not the first mission to carry covers. Dozens were carried on each flight from Apollo 11 onwards (see Table 1 for the complete list) and, as Apollo 15 Commander Dave Scott recalled in his book, the whole business had probably been building since Mercury, through Gemini and into Apollo. [4] People had a fascination with objects that had been carried into space, and that became more and more popular – and valuable – as the programs progressed. Right from the start of the Mercury program, each astronaut had been allowed to carry a certain number of personal items onboard, with NASA’s permission, in 1 A first version of this material was issued as Apollo 15 Cover Scandal in Orbit No. -

Psychology of Space Exploration Psychology of About the Book Douglas A

About the Editor Contemporary Research in Historical Perspective Psychology of Space Exploration Psychology of About the Book Douglas A. Vakoch is a professor in the Department As we stand poised on the verge of a new era of of Clinical Psychology at the California Institute of spaceflight, we must rethink every element, including Integral Studies, as well as the director of Interstellar Space Exploration the human dimension. This book explores some of the Message Composition at the SETI Institute. Dr. Vakoch Contemporary Research in Historical Perspective contributions of psychology to yesterday’s great space is a licensed psychologist in the state of California, and Edited by Douglas A. Vakoch race, today’s orbiter and International Space Station mis- his psychological research, clinical, and teaching interests sions, and tomorrow’s journeys beyond Earth’s orbit. include topics in psychotherapy, ecopsychology, and meth- Early missions into space were typically brief, and crews odologies of psychological research. As a corresponding were small, often drawn from a single nation. As an member of the International Academy of Astronautics, intensely competitive space race has given way to inter- Dr. Vakoch chairs that organization’s Study Groups on national cooperation over the decades, the challenges of Interstellar Message Construction and Active SETI. communicating across cultural boundaries and dealing Through his membership in the International Institute with interpersonal conflicts have become increasingly of Space Law, he examines -

The Soviet Moon Program

The Moon Race [July 1969] – down to the wire! JAMES OBERG JULY 17, 2019 SPACE CENTER HOUSTON APOLLO-11 FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY WWW.JAMESOBERG.COM [email protected] OVERVIEW– JULY 1969 Unexpected last-minute drama was added to Apollo-11 by the appearance of a robot Soviet moon probe that might have returned lunar samples to Earth just before the astronauts got back. We now know that even more dramatic Soviet moon race efforts were ALSO aimed at upstaging Apollo, hoping it would fail. But it was the Soviet program that failed -- and they did their best to keep it secret. These Soviet efforts underscored their desperation to nullify the worldwide significance of Apollo-11 and its profound positive impact, as JFK had anticipated, on international assessments of the relative US/USSR balance of power across the board -- military, commercial, cultural, technological, economic, ideological, and scientific. These were the biggest stakes in the entire Cold War, whose final outcome hung in the balance depending on the outcome of the July 1969 events in space. On July 13, 1969, three days before Apollo-11, the USSR launched a robot probe to upstage it DAY BEFORE APOLLO-11 LANDING – BOTH SPACECRAFT ORBITING MOON IN CRISS-CROSS ORBITS THE SOVIET PROBE GOT TO THE MOON FIRST & WENT INTO ORBIT AROUND IT AS APOLLO BEGAN ITS MISSION https://i.ebayimg.com/images/g/T6UAAOSwDJ9crVLo/s-l1600.jpg https://youtu.be/o16I8S3MMo4 A FEW YEARS LATER, ONCE A NEW MISSION HAD SUCCEEDED, MOSCOW RELEASED DRAWINGS OF THE VEHICLE AND HOW IT OPERATED TO LAND, RETRIEVE SAMPLES, AND RETURN TO EARTH Jodrell Bank radio telescope in Britain told the world about the final phase of the Luna 15 drama, in a news release: "Signals ceased at 4.50 p.m. -

Then and Now in Space

VOLUME 18 ISSUE 4 An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education Program Then and Now in Space AGATE BY JONATHAN BARTLETT FOR THE WASHINGTON POST ■ Post Reprint: “Apollo 8: NASA’s first moonshot was a bold and terrifying improvisation” ■ KidsPost Reprint: “A new era in spaceflight: Back to the moon on the way to Mars” ■ KidsPost Graphic Reprint: “The Journey to Space” ■ Student Activity: Where We Have Been, Where We Will Go ■ Student Activity: What Colors? What Shape? What Marvels! January 14, 2019 ©2019 THE WASHINGTON POST VOLUME 18 ISSUE 5 An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education Program Retropolis Apollo 8: NASA’s first moonshot was a bold and terrifying improvisation BY JOEL ACHENbaCH • Originally Published December 21, 2018 Walter Cronkite held a tiny model of the Apollo 8 spacecraft and strode across a darkened studio where two dangling spheres represented Earth and the moon. This was the CBS Evening News, Dec. 20, 1968, and three Apollo 8 astronauts were scheduled to blast off the following morning on a huge Saturn V rocket. Cronkite explained that the astronauts would fly for three days to the vicinity AP of the moon, fire an engine to slow Apollo 8 lifts off from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Dec. 21, 1968. the spacecraft and enter lunar orbit, circle the moon 10 times, then fire the wrong: “Just how do we tell Susan astronauts said, according to Morrow engine a final time to return to Earth Borman, ‘Frank is stranded in orbit Lindbergh’s subsequent article in and enter the atmosphere at 25,000 around the moon’?” LIFE magazine. -

"UFO" Sightings James Oberg

Astronaut "UFO" Sightings James Oberg The glamour and drama of manned space-flights has been transferred to the UFO field via a highly publicized group of "UFO sightings" and photographs allegedly made by American and Russian space-pilots. Hardly a UFO book or movie fails to mention that "astronauts have seen UFOs too." Careful examination of each and every one of these stories (and they total more than 20 or 30) can produce quite reasonable explanations, in terms of visual phenomena associated with space flights. On a visit to the NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston in July 1976, Dr. J. Allen Hynek, of the Center for UFO Studies, concluded that none of the authentic cases (as opposed to the majority of reports, which are ficti- tious) really had anything to do with the "real UFO phenomenon." Skeptical investigators, while pleased that Hynek had dismissed all "astronaut UFO reports" as unreliable, have insisted that this body of stories has quite a lot to do with the major problems besetting the UFO community. How, they ask, can a body of stories so patently false and unreliable obtain such seeming authenticity simply by being passed back and forth among researchers without ever being seriously investigated? Is this a characteristic of UFO stories in general; and if so, the skeptics ask, can a study of how the "astronaut UFO" myth began and flourished help us to understand better the UFO phenomenon in general? Hynek's disavowal of the stories came after his book Edge of Real- ity (coauthored with Jacques Vallee) carried a long list of astronaut sight- ing reports. -

Dead Cosmonauts >> Misc

James Oberg's Pioneering Space powered by Uncovering Soviet Disasters >> Aerospace Safety & Accidents James Oberg >> Astronomy >> Blogs Random house, New York, 1988 >> Chinese Space Program Notes labeled "JEO" added to electronic version in 1998 >> Flight to Mars >> Jim's FAQ's >> Military Space Chapter 10: Dead Cosmonauts >> Misc. Articles Page 156-176 >> National Space Policy >> Other Aerospace Research >> Reviews The family of Senior Lieutenant Bondarenko is to be provided with everything necessary, as befits the >> Russian Space Program family of a cosmonaut. --Special Order, signed by Soviet Defense Minister R. D. Malinovskiy, April 16, >> Space Attic NEW 1961, classified Top Secret. NOTE: Prior to 1986 no Soviet book or magazine had ever mentioned the >> Space Folklore existence of a cosmonaut named Valentin Bondarenko. >> Space History >> Space Operations In 1982, a year after the publication of my first book, Red Star in Orbit. I received a wonderful picture >> Space Shuttle Missions from a colleague [JEO: Arthur Clarke, in fact] who had just visited Moscow. The photo showed >> Space Station cosmonaut Aleksey Leonov, hero of the Soviet Union, holding a copy of my book-- and scowling. >> Space Tourism Technical Notes >> Leonov was frowning at a picture of what I called the "Sochi Six," the Russian equivalent of our "original >> Terraforming seven" Mercury astronauts. They were the top of the first class of twenty space pioneers, the best and the boldest of their nation, the ones destined to ride the first manned missions. The picture was taken at the Black Sea resort called Sochi in May 1961, a few weeks after Yuriy Gagarin's history-making flight. -

Vanishing Cosmonauts -- with Photos

Cosmonauts Who Weren’t There James Oberg June 24 2012 [illustrations added] In the years between the end of the Apollo program (1975) and the first orbital flights of the space shuttle (1981), when I was on the Mission Control Center team in Houston preparing for the first launch of ‘Columbia’, one of my additional duties was to provide background briefings for new personnel there. I found that one particular set of “space history” slides made one audience especially nervous. It wasn’t what the slides showed, but rather, what they did NOT show. The pictures were of groups of Russian cosmonauts, smiling confidently for the cameras. But what made the audience laugh -- at first -- was that subsequent versions of the very same group photographs had gaps. Faces clearly seen in the first versions had vanished to the retoucher’s airbrush. My most nervous audience was the new ‘space shuttle astronaut selection’, 35 men and women chosen in 1978 to supplement the two dozen Apollo veterans and as-yet unflown rookies from that era. They were sobered to realize the apparent implication of the forged Russian cosmonaut photographs -- if a space trainee screwed up, he (or she) could just disappear. Now, I’m not making this up. To prevent that from ever happening to themselves, they all vowed not to screw up. As an added defense to photo erasure, they joked, in any group photo sessions they would entwine their arms very tightly with each other. And it really was funny, after all. Here were clumsy Soviet propagandists obviously trying to conceal the existence of several individuals who had been members of their first cosmonaut teams. -

Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey New Brunswick an Interview with Candy Torres for the Rutgers Oral History Archives I

RUTGERS, THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW JERSEY NEW BRUNSWICK AN INTERVIEW WITH CANDY TORRES FOR THE RUTGERS ORAL HISTORY ARCHIVES INTERVIEW CONDUCTED BY KATHRYN TRACY RIZZI BRANCHBURG, NEW JERSEY APRIL 16, 2020 TRANSCRIPT BY JESSE BRADDELL Kathryn Tracy Rizzi: This begins an oral history interview with Candy Torres, on April 16, 2020, with Kate Rizzi. Thank you so much for doing this interview series with me. Candy Torres: Thank you. KR: Last time, we left off talking about your early career, when you were working at Princeton and then McDonnell-Douglas. What challenges do you think you faced in the early part of your career? CT: At Princeton, the job qualifications in the ad were: "Some knowledge of Astrophysics or Astronomy, or Physics or Computers." In developing my individual major, I had satisfied all requirements with "and" instead of "or." In a sense, I had already met the challenges of my new job. The on-the-job training was awesome. The astrophysicist who hired me, Dr. Ted Snow, was easygoing and provided me with extra opportunities beyond my assigned work tasks. The first day I started, he said to me, "You're a professional." He left it up to me define it. I made sure all of my actions represented myself, my boss, and the department in the highest standards. I felt proud. I was trained in my job by the guy who was leaving, and after that, I had a friendly group coworkers to coordinate with. My interactions with Dr. Snow was to report on the status of astrophysicists' experiment data and provide the quarterly NASA reports. -

Vol 24 Issue 2

Resea r c h Outrjeach^ en g a g em en t Summer 2010 Volume XXIV, No. 2 Leading and Managing through Influence Challenges and Responses Dr. Raymond A. Shulstad, Brigadier General, USAF, Retired with Lt Col Richard D. Mael, USAF, Retired The Role of Airpower in Active Missile Defense Col Mike Corbett, USAF, Retired Paul Zarchan New Horizons Coalition Space Operations Lt Col Thomas G. Single, USAF Beddown Options for Air National Guard C-27J Aircraft Supporting Domestic Response Col John Conway, USAF, Retired Building an Offensive and Decisive PLAAF A Critical Review of Lt Gen Liu Yazhou’s The Centenary of the Air Force Guocheng Jiang To Fly. F ight , and Win ... In Air . S pace, and Cyber space Chief of Staff, US Air Force Gen Norton A. Schwartz Commander, Air Education and Training Command Gen Stephen R. Lorenz http://www.af.mil Commander, Air University Lt Gen Allen G. Peck Director, Air Force Research Institute Gen John A. Shaud, USAF. Retired Chief, Professional Journals Lt Col Paul D. Berg Deputy Chief, Professional Journals Maj Darren K. Stanford http://www.aetc.randolph.af.mil Editor Capt Lori Katowich Professional Staff Marvin W. Bassett, Contributing Editor Tammi K. Long, Editorial Assistant Daniel M. Armstrong, Illustrator L. Susan Fair, Illustrator Ann Bailey, Prepress Production Manager The Air and Space Power Journal (ISSN 1554-2505), Air Force Recurring Publication 10-1, published quarterly, http://www.au.af.mil is the professional journal of the United States Air Force. It is designed to serve as an open forum for the presentation and stimulation of innovative thinking on military doctrine, strategy, force structure, readiness, Air and Space Power Journal and other matters o f national defense. -

Union Calendar No. 488 105Th Congress, 2D Session – – – – – – – – – – – – House Report 105–847

1 Union Calendar No. 488 105th Congress, 2d Session ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± House Report 105±847 SUMMARY OF ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES FOR THE ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS JANUARY 2, 1999 JANUARY 2, 1999.ÐCommitted to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 53±706 WASHINGTON : 1999 COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., Wisconsin, Chairman SHERWOOD L. BOEHLERT, New York GEORGE E. BROWN, JR., California RMM* HARRIS W. FAWELL, Illinois RALPH M. HALL, Texas CONSTANCE A. MORELLA, Maryland BART GORDON, Tennessee CURT WELDON, Pennsylvania JAMES A. TRAFICANT, JR., Ohio DANA ROHRABACHER, California TIM ROEMER, Indiana JOE BARTON, Texas JAMES A. BARCIA, Michigan KEN CALVERT, California EDDIE BERNICE JOHNSON, Texas ROSCOE G. BARTLETT, Maryland ALCEE L. HASTINGS, Florida VERNON J. EHLERS, Michigan** LYNN N. RIVERS, Michigan DAVE WELDON, Florida ZOE LOFGREN, California MATT SALMON, Arizona MICHAEL F. DOYLE, Pennsylvania THOMAS M. DAVIS, Virginia SHEILA JACKSON-LEE, Texas GIL GUTKNECHT, Minnesota BILL LUTHER, Minnesota MARK FOLEY, Florida DEBBIE STABENOW, Michigan THOMAS W. EWING, Illinois BOB ETHERIDGE, North Carolina CHARLES W. ``CHIP'' PICKERING, NICK LAMPSON, Texas Mississippi DARLENE HOOLEY, Oregon CHRIS CANNON, Utah LOIS CAPPS, California KEVIN BRADY, Texas BARBARA LEE, California MERRILL COOK, Utah BRAD SHERMAN, California PHIL ENGLISH, Pennsylvania VACANCY GEORGE R. NETHERCUTT, JR., Washington TOM A. COBURN, Oklahoma PETE SESSIONS, Texas VACANCY TODD R. SCHULTZ, Chief of Staff BARRY C. BERINGER, Chief Counsel PATRICIA S. SCHWARTZ, Chief Clerk/Administrator VIVIAN A. TESSIERI, Legislative Clerk ROBERT E. PALMER, Democratic Staff Director *Ranking Minority Member. -

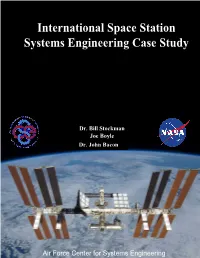

ISS Systems Engineering Case Study

International Space Station Systems Engineering Case Study Dr. Bill Stockman InternationalJoe SpaceBoyle Station Systems EngineeringDr. John Bacon Case Study Air Force Center for Systems Engineering Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited The views expressed in this Case Study are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of NASA, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the United States Government. FOREWORD One of the objectives of the Air Force Center for Systems Engineering (AFCSE) is to develop case studies focusing on the application of systems engineering principles within various aerospace programs. The intent of these case studies is to examine a broad spectrum of program types and a variety of learning principles using the Friedman-Sage Framework to guide overall analysis. In addition to this case, the following studies are available at the AFCSE website. ■ Global Positioning System (space system) ■ Hubble Telescope (space system) ■ Theater Battle Management Core System (complex software development) ■ F-111 Fighter (joint program with significant involvement by the Office of the Secretary of Defense) ■ C-5 Cargo Airlifter (very large, complex aircraft) ■ A-10 Warthog (ground attack) ■ Global Hawk ■ KC-135 Simulator These cases support practitioners of systems engineering and are also used in the academic instruction in systems engineering within military service academies and at both civilian and military graduate schools. Each of the case studies comprises elements of success as well as examples of systems engineering decisions that, in hindsight, were not optimal. Both types of examples are useful for learning. Plans exist for future case studies focusing on various space systems, additional aircraft programs, munitions programs, joint service programs, logistics-led programs, science and technology/laboratory efforts, and a variety of commercial systems.