4.7 Sediment Traps and Basins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deposition Patterns and Rates of Mining-Contaminated Sediment Within a Sedimentation Basin System, S.E

BearWorks Institutional Repository MSU Graduate Theses Spring 2017 Deposition Patterns and Rates of Mining- Contaminated Sediment within a Sedimentation Basin System, S.E. Missouri Joshua Carl Voss Missouri State University - Springfield, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, Environmental Monitoring Commons, and the Hydrology Commons Recommended Citation Voss, Joshua Carl, "Deposition Patterns and Rates of Mining-Contaminated Sediment within a Sedimentation Basin System, S.E. Missouri" (2017). MSU Graduate Theses. 3074. http://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3074 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The orkw contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEPOSITION PATTERNS AND RATES OF MINING-CONTAMINATED SEDIMENT WITHIN A SEDIMENTATION BASIN SYSTEM, BIG RIVER, S.E. MISSOURI A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University ATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science, Geospatial Sciences in Geography, Geology, and Planning By Josh C. Voss May 2017 Copyright 2017 by Joshua Carl Voss ii DEPOSITION PATTERNS AND RATES OF MINING-CONTAMINATED SEDIMENT WITHIN A SEDIMENTATION BASIN SYSTEM, BIG RIVER, S.E. MISSOURI Geography, Geology, and Planning Missouri State University, May 2017 Master of Science Josh C. Voss ABSTRACT Flooding events exert a dominant control over the deposition and formation of floodplains. The rate at which floodplains form depends on flood magnitude, frequency, and duration, and associated sediment transport capacity and supply. -

State-Of-The-Practice: Evaluation of Sediment Basin Design, Construction, Maintenance, and Inspection Procedures

Research Report No. 1 Project Number: 930-791 STATE-OF-THE-PRACTICE: EVALUATION OF SEDIMENT BASIN DESIGN, CONSTRUCTION, MAINTENANCE, AND INSPECTION PROCEDURES Prepared by: Wesley C. Zech Xing Fang Christopher Logan August 2012 DISCLAIMERS The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of Auburn University or the Alabama Department of Transportation. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. NOT INTENDED FOR CONSTRUCTION, BIDDING, OR PERMIT PURPOSES Wesley C. Zech, Ph.D. Xing Fang, Ph.D., P.E., D.WRE Research Supervisors ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Material contained herein was obtained in connection with a research project “Assessing Performance Characteristics of Sediment Basins Constructed in Franklin County,” ALDOT Project 930-791, conducted by the Auburn University Highway Research Center. Funding for the project was provided by the Alabama Department of Transportation. The funding, cooperation, and assistance of many individuals from each of these organizations are gratefully acknowledged. The authors would like to acknowledge and thank all the responding State Highway Agencies (SHAs) for their participation and valuable feedback. The project advisor committee includes Mr. Buddy Cox, P.E., (Chair); Mr. Larry Lockett, P.E., (former chair); Mr. James Brown, P.E.; Mr. Barry Fagan, P.E.; Mr. Skip Powe, P.E.; Ms. Kaye Chancellor Davis, P.E.; Ms. Michelle Owens (RAC Liaison), and Ms. Kristy Harris (FHWA Liaison). iii ABSTRACT The following document is the summary of results from a survey that was conducted to evaluate the state-of-the-practice for sediment basin design, construction, maintenance, and inspection procedures by State Highway Agencies (SHAs) across the nation. -

SEDIMENT BASIN (No.) Code 350

SEDIMENT BASIN (No.) Code 350 Natural Resources Conservation Service Conservation Practice Standard I. Definition filter strips, etc., to reduce the amount of sediment flowing into the basins. A basin constructed to collect and store debris or sediment. The basin shall be located to intercept sediment before it enters streams, lakes, and wetlands. For II. Purpose maximum effectiveness, the basin must be located close to the sediment source. To preserve the capacity of reservoirs, lakes, wetlands, ditches, canals, diversions, waterways, and The capacity of the sediment basin shall equal streams; to prevent undesirable deposition on bottom the volume of sediment expected to be trapped at lands and developed areas; to trap sediment the site during the planned life of the basin or the originating from construction sites; and to reduce or improvements it is designed to protect. abate pollution by providing basins for deposition and storage of silt, sand, gravel, stone, agricultural Sediment basins meeting these design criteria are wastes, and other detritus. assumed to have an 80% trapping efficiency. III. Conditions Where Practice Applies volume = calculated erosion * planned life * SDR * trap efficiency * 23.5 ft3/ton This practice applies where physical conditions or land ownership preclude treatment of a sediment Where: source or where a sediment basin offers the most 3 practical solution to reduce sediment delivery to Volume = cubic feet (ft ) downstream areas. Calculated erosion = sheet and rill, gullies, etc. (Tons / year) Sediment basins having the primary purpose of controlling suspended solids loading and attached SDR= sediment delivery ratio pollutants from runoff with a permanent pool of Trap Efficiency Assumed to be 80% watershall meet the criteria set forth in Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) Standard If it is determined that periodic removal of 1001, Wet Detention Basin. -

Sediment Basin

Water Resources Division Sediment Basin Definition Sediment basins are temporary ponds with appropriate control structures, used on construction sites to capture eroded or disturbed soil that are washed off during or after rainstorms or other runoff events. Sediment basins are designed to protect the water quality of nearby streams, rivers, lakes, and wetlands, and to protect neighboring properties from damage. Some sediment basins are converted to permanent storm water controls following the completion of construction activity. Purpose and Description The primary purpose of sediment basins is to prevent sediment from entering streams, rivers, lakes, or wetlands. They do this by collecting and detaining runoff, allowing suspended solids to settle out prior to the runoff leaving a site. Sediment basins are also sometimes called settling basins, sumps, debris basins, or dewatering basins. Pollutant Controlled: Suspended solids Treatment Mechanism: Settling Removal Efficiency Sediment basins remove only 70 to 80 percent of medium- and coarse-sized sediment particles, so use them in conjunction with other erosion control best management practices (BMPs). Sediment basins are not effective at controlling fine soil particles such as silt or clay. Companion and Alternative BMPs Construction Barrier Mulching Polyacrylamide Riprap-Stabilized Outlet Seeding Sodding www.michigan.gov/deq MDEQ NPS BMP Manual SB-1 Rev20190208 Advantages and Disadvantages Advantages Sediment basins are a cost-effective measure for treating sediment-laden runoff from drainage areas ranging from five (5) to 100 acres in size, with soil particle sizes of predominantly sand, or medium to large silt. Sediment basins are relatively easy to construct. Disadvantages The construction and proper functioning of sediment basins require adequate space and topography. -

Tennessee Erosion & Sediment Control Handbook

TENNESSEE EROSION & SEDIMENT CONTROL HANDBOOK A Stormwater Planning and Design Manual for Construction Activities Fourth Edition AUGUST 2012 Acknowledgements This handbook has been prepared by the Division of Water Resources, (formerly the Division of Water Pollution Control), of the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation (TDEC). Many resources were consulted during the development of this handbook, and when possible, permission has been granted to reproduce the information. Any omission is unintentional, and should be brought to the attention of the Division. We are very grateful to the following agencies and organizations for their direct and indirect contributions to the development of this handbook: TDEC Environmental Field Office staff Tennessee Division of Natural Heritage University of Tennessee, Tennessee Water Resources Research Center University of Tennessee, Department of Biosystems Engineering and Soil Science Civil and Environmental Consultants, Inc. North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Georgia Department of Natural Resources California Stormwater Quality Association ~ ii ~ Preface Disturbed soil, if not managed properly, can be washed off-site during storms. Unless proper erosion prevention and sediment control Best Management Practices (BMP’s) are used for construction activities, silt transport to a local waterbody is likely. Excessive silt causes adverse impacts due to biological alterations, reduced passage in rivers and streams, higher drinking water treatment costs for removing the sediment, and the alteration of water’s physical/chemical properties, resulting in degradation of its quality. This degradation process is known as “siltation”. Silt is one of the most frequently cited pollutants in Tennessee waterways. The division has experimented with multiple ways to determine if a stream, river, or reservoir is impaired due to silt. -

Maintaining Your Detention Basin: a Guidebook for Private Owners in Clermont County

Maintaining Your Detention Basin: A Guidebook for Private Owners in Clermont County A well maintained detention basin BASINS Your detention basin is a storm water best management practice (BMP) designed to tempo- INTRODUCTION rarily capture and hold storm water runoff during periods of heavy rain, and slowly release this flow over a period of one or two days so it minimizes flooding and streambank erosion problems downstream. They also help remove sediments from storm water runoff, which helps improve the quality of local streams. Like most other things, a detention basin may not function properly or it may fail prematurely if not properly maintained. Once a detention basin fails, it is often very expensive to correct. Many detention basins are located on private property, including parcels of land owned and maintained by a homeowners association (HOA). Local governments do not have the au- thority to maintain components of the storm sewer system on private property, including detention basins. Rather, these are the responsibility of the lot owner to maintain. Whether you are an individual property owner, a homeowner’s association representative, or a residential/commercial property manager, this Guidebook will help answer questions and provide you with instructions for basin maintenance activities. Routine maintenance will prolong the life of your detention basin, improve its appearance, help prevent flooding and property damage, and enhance local streams and lakes. WHAT ARE DETENTION BASINS AND WHY ARE THEY IMPORTANT? When land is altered to build homes and other developments, the natural system of trees and plants over relatively spongy soil is replaced with harder surfaces like sidewalks, streets, decks, roofs, driveways and even lawns over compacted soils. -

Chapter 23: Detention Basin Standards

CHAPTER 23: DETENTION BASIN STANDARDS 23.00 Introduction and Goals 23.01 Administration 23.02 Standards 23.03 Standard Attachments 23.1 City of Champaign Manual of Practice March 2002 Chapter 23: Detention Basin Standards 23.00 INTRODUCTION AND GOALS A. The purpose of this chapter is to explain the City’s policy regarding the ownership, design, construction, and maintenance responsibility for detention basins. Detention basins are used to collect and hold stormwater runoff for a period of time to compensate for increases in stormwater runoff caused by reduced ground surface perviousness due to activities such as paving or building construction. B. Detention basins historically range in size from backyard detention provided by swales, to large regional detention ponds. Detention basins may be wet or dry bottomed. Residential backyard or sideyard single lot detention is not allowed. Construction of detention for individual lots of less than 5 acres is not recommended; alternate methods such as payment in lieu of detention or one basin for the entire subdivision or development are preferred. 23.01 ADMINISTRATION A. This chapter applies to detention basins within the City limits and the 1-1/2 mile extra territorial jurisdiction. B. Detention basin construction is required for certain conditions by the City of Champaign Stormwater Management Regulations. C. Detention basin design shall be reviewed by the City of Champaign through either of the following: 1. Subdivision plan review 2. Grading and drainage plan review 3. Alternate construction plan review (typically public improvements) 23.02 STANDARDS The following standards apply to detention basins: A. Referenced Standards: Design standards for detention basin design and construction shall comply with the provisions of the following, unless otherwise stated by this manual. -

Reclamation of Tailings Ponds

Journal American Society of Mining and Reclamation, 2012 Volume 1, Issue 1, COMPARISON OF HYDROLOGIC CHARACTERISTICS FROM TWO DIFFERENTLY RECLAIMED TAILINGS PONDS; GRAVES MOUNTAIN, LINCOLNTON, GA1 Gwendelyn Geidel2 Abstract: This study compares and evaluates the hydrologic characteristics between two kyanite ore process tailings ponds that were reclaimed with different reclamation strategies; one reclaimed with an impermeable membrane and the other with an open, surface reconfiguration (OSR) methodology. During the extraction and processing of kyanite ore from the Graves Mountain mine, Lincoln County, Georgia, fine grained tailings were produced. The tailings were transported by slurry pipeline to various tailings ponds which were created by the construction of dams using on-site materials. The first study site, referred to as the Pyrite Pond (PP), was constructed and filled during the 1960’s and early 1970’s. In early 1992, the PP was capped with an impermeable membrane, covered with a thin soil veneer and vegetated and in 1998 the upslope reclamation was completed. The second tailings pond, referred to as the East Tailings Pond (ETP), was constructed and filled in the 1970’s and early 1980’s and was reclaimed in 1995-96 by surface reconfiguration and the addition of soil amendments. Piezometers and wells were installed into the two tailings ponds and also in close proximity to the tailings ponds. While the initial study was aimed at comparing the two reclamation strategies, it became apparent that the ground water was a dominant factor. Results of the evaluation of the potentiometric surface data for varying depths within each tailings pond indicate that while both tailings ponds exhibit delayed response to precipitation events suggesting infiltration effects, the delay in the ETP deep wells and PP wells could not be adequately described by a surface infiltration model. -

5.00 Storm Water Pond Systems

This guidance is not a regulatory document and should be considered only informational and supplementary to the MPCA permits (such as the construction storm water general permit or MS4 permit) and local regulations. CHAPTER 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 5.00 STORMWATER-DETENTION PONDS............................................................................5.00-1 5.01 Pond Design Criteria: SYSTEM DESIGN.........................................................5.01-1 5.02 Pond Design Criteria: POND LAYOUT AND SIZE.........................................5.02-1 5.03 Pond Design Criteria: MAIN TREATMENT CONCEPTS...............................5.03-1 5.04 Pond Design Criteria: DEAD STORAGE VOLUME .......................................5.04-1 5.05 Pond Design Criteria: EXTENDED DETENTION ...........................................5.05-1 5.06 Pond Design Criteria: POND OUTLET STRUCTURES ..................................5.06-1 5.07 Pond Design Criteria: OPERATION AND MAINTENANCE..........................5.07-1 5.08 Pond Design Criteria: SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS ....................................5.08-1 5.10 STORMWATER POND SYSTEMS..........................................................................5.10-1 5.11 Pond Systems: ON-SITE VERSUS REGIONAL PONDS ................................5.11-1 5.12 Pond Systems: ON-LINE VERSUS OFF-LINE PONDS ..................................5.12-1 5.13 Pond Systems: OTHER POND SYSTEMS.......................................................5.13-1 5.20 Ponds: EXTENDED-DETENTION PONDS..............................................................5.20-1 -

Maine Erosion and Sediment Control Practices Field Guide for Contractors

Maine Erosion and Sediment Control Practices Field Guide for Contractors Maine Department of Environmental Protection ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Production 2014 Revision: Marianne Hubert, Senior Environmental Engineer, Division of Watershed Management, Bureau of Land and Water Quality, Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). Illustrations: Photos obtained from SJR Engineering Inc., Shaw Brothers Construction Inc., Bar Mills Ecological, Maine Department of Transportation (MaineDOT), Maine Land Use Planning Commission (LUPC) and Maine Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). TECHNICAL REVIEW COMMITTEE: The following people participated in the revision of this manual: Steve Roberge, SJR Engineering, Inc., Augusta Ross Cudlitz, Engineering Assistance & Design, Inc., Yarmouth Susan Shaller, Bar Mills Ecological, Buxton David Roque, Department of Agriculture, Conservation & Forestry Peter Newkirk, MaineDOT Bob Berry, Main-Land Development Consultants Daniel Shaw, Shaw Brothers Construction Peter Hanrahan, E.J. Prescott William Noble, William Laflamme, David Waddell, Kenneth Libbey, Ben Viola, Jared Woolston, and Marianne Hubert of the Maine DEP Revision (2003): The manual was revised and reorganized with illustrations (original manual, Salix, Applied Earthcare and Ross Cudlitz, Engineering Assistance & Design, Inc.). Original Manual (1991): The original document was funded from a US Environmental Protection Agency Federal Clean Water Act grant to the Maine Department of Environmental Protection, Non- Point Source Pollution Program and developed -

Sediment Basin Design Fact Sheet

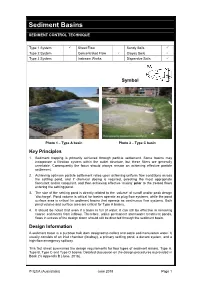

Sediment Basins SEDIMENT CONTROL TECHNIQUE Type 1 System Sheet Flow Sandy Soils Type 2 System Concentrated Flow Clayey Soils Type 3 System Instream Works Dispersive Soils Symbol Photo 1 – Type A basin Photo 2 – Type C basin Key Principles 1. Sediment trapping is primarily achieved through particle settlement. Some basins may incorporate a filtration system within the outlet structure, but these filters are generally unreliable. Consequently the focus should always remain on achieving effective particle settlement. 2. Achieving optimum particle settlement relies upon achieving uniform flow conditions across the settling pond, and if chemical dosing is required, selecting the most appropriate flocculant and/or coagulant, and then achieving effective ‘mixing’ prior to the treated flows entering the settling pond. 3. The size of the settling pond is directly related to the ‘volume’ of runoff and/or peak design ‘discharge’. Pond volume is critical for basins operate as plug flow systems; while the pond surface area is critical for sediment basins that operate as continuous flow systems. Both pond volume and surface area are critical for Type A basins. 4. It should be noted that even if a basin is full of water, it can still be effective in removing coarse sediments from inflows. Therefore, unlike permanent stormwater treatment ponds, flows in excess of the design storm should still be directed through the sediment basin. Design Information A sediment basin is a purpose built dam designed to collect and settle sediment-laden water. It usually consists of an inlet chamber (forebay), a primary settling pond, a decant system, and a high-flow emergency spillway. -

Location & Design Manual, Volume 2

Ohio Department of Transportation Central Office • 1980 West Broad Street • Columbus, OH 43223 John Kasich, Governor • Jerry Wray, Director Date: January 20, 2017 To: All Current Holders of the Location and Design Manual, Volume 2 Re: Location and Design Manual, Volume Two Revisions Transmitted herewith are revisions to the Location and Design Manual, Volume 2. The following revisions have been made: • Revisions / Additions in Red • Preface – Added clarification to Purpose • 1002.2.4 – Updated last sentence of last paragraph • 1005.1.4 – Updated guidance for documentation requirements in FEMA Zones • 1104.1– Added paragraph noting the availability of Sample Plan Sheets • 1105.1– Added paragraph noting the availability of Sample Plan Sheets • 1115.3 – Clarified language on which projects are exempt from water quantity treatment • 1115.3 – Moved stream protection BMP to 1117.8 as a stand-alone BMP • 1115.6.1 – Changed “pavement” to “impervious area” • 1115.6.2 – Changed language for consistency with other sections. • 1115.6.3 – Added new section Pedestrian Facilities and Shared Use Paths • 1115.7 – Clarified language for “Aix” and “Ain” with no changes to requirements • 1116, 1117 – Added “EDA treatment credit” for consistency with L&D Vol. 3 requirements for the Project Site Plan throughout the sections • 1116.2 – Added reference to BMP design resources on ODOT’s website • 1117.2 – Changed “vegetated” to “grassed” across the section • 1117.2.1 – Removed prohibition of discharging an underdrain outlet to a Vegetated Filter Strip. • 1117.2.1 – Added new section for narrow Vegetated Filter Strips for pedestrian facilities and shared use paths. • 1117.2.2 – Clarified treatment credit for Vegetated Biofilters.