Passover 5778 the Shofar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hills Are Alive

18 ★ FTWeekend 2 May/3 May 2015 House Home perfect, natural columns of Ginkgo biloba“Menhir”. Pergolasandterraces,whichdripwith trumpet vine in summer, look down on standing stones and a massive “stone Returning to Innisfree after 15 years, Jane Owen henge”framingthelake. A grass dome, “possibly a chunk of mountain top or some such cast finds out whether this living work of art in down by the glacier that created the lake”, says Oliver, is echoed by clipped New York State retains its magic domes of Pyrus calleryana, the pear nativetoChina. Beyond the white pine woods, the path becomes boggy and narrow, criss- crossed with tree roots, moss and fungi. A covered wooden bridge reminds visi- torsthisisanall-Americanlandscape. Buteventheall-American,maplesyr- The hills up-supplying sugar maples here come with a twist. They are Acer saccharum “Monumentale” and, like the ginkgos, are naturally column-shaped. Innis- free’s American elms went years ago, are alive . victims of Dutch elm disease, but the Hemlocks are hanging on, with the help ofinsecticidetofightthewoollyadelgid. Larger garden pests include beavers, which have built a lodge 100m from the bout 90 miles west of the Iwillariseandgonow,andgoto bubble fountain, and deer. At least the thrumming heart of New Innisfree, . latter has a use, as part of a programme York City is a landscape Ihearlakewaterlappingwithlow of hunters donating food for those in that stirs my soul. I rate soundsbytheshore; need. So the dispossessed eat venison, it along with Villa Lante, WhileIstandontheroadway,oron albeitthetough,end-of-seasonsort. AThe Garden of Cosmic Speculation, thepavementsgrey, All is beautiful, but there’s one Liss Ard in Ireland, Little Sparta, Nin- Ihearitinthedeepheart’score. -

Calling All Crafters, Artisans, Demonstrators, and Vendors!! More Information to Follow. See Our Website for Updates

Calling all Crafters, Artisans, Demonstrators, and Vendors!! Shepherd of the Hills will be hosting 3 exciting events this year. We invite you to join in on the fun. APRIL 9th, 10th, & 11th —Shepherd’s Junk Fair Rusty junk, painted furniture, repurposed items, vintage décor, & antiques. MAY 15th & 16th —Old Ozarks Settlers Days Kicking off the 2021 Season of The Shepherd of the Hills play, The Society of Ozarkian Hillcrofters will be helping us celebrate our regional history & heritage. We are looking for demonstrating artisans, speakers, primitive arts, musicians, & historians. We are offering free booth space for demonstrating artisans (who are not selling products) and there will be no charge for non-profit organizations. SEPTEMBER 10th, 11th, & 12th –Fall Craft Fair We had such a successful event last year, we are doing it again! All products must be handcrafted or repurposed items. Demonstrating crafters are welcome. All events are OUTDOORS. For the safety of others, there will be no vehicle traffic inside the gates during event hours. Participants must commit to all days of their chosen event. We are not accepting imported, manufactured, or direct sales items. All Booth spaces are 12’ x 12’ Indoor/Covered spaces are limited & available on a first come first serve basis. More information to follow. See our website for updates. 5586 W 76 Country Blvd. Branson, MO 65616 PH: 417.334.4191 FAX: 417.334.4464 theshepherdofthehills.com 2021 Vendor Request for Space Early Application ~Circle chosen event(s)~ Shepherd’s Junk Fair Old Ozarks -

Beverages Griddle Cakes & Cereal

noshville_NEW_print 1/11/18 11:09 AM Page 1 Beverages Griddle Cakes & Cereal Small Large Griddle Orange Juice (Fresh Squeezed) 2.49 4.49 Griddle Cakes (2) 4.99 (3) 6.49 Toppings Grapefruit Juice (Fresh Squeezed) 2.49 4.49 Chocolate Chip Griddle Cakes (2) 5.99 (3) 7.49 Apple Juice 1.99 3.99 Strawberry • 1-Griddle Cake, 1-Egg, 1-Bacon or Sausage 6.49 Tomato Juice or V8 1.99 3.99 or Blueberry • 2-Griddle Cakes, 2-Eggs, 2-Bacon or Sausage 9.99 Pineapple Juice 1.99 3.99 Compote • 1-French Toast, 1-Egg, 1-Bacon or Sausage 7.99 Add $.99 Cranberry Juice 1.99 3.99 • 2-French Toast, 2-Eggs, 2-Bacon or Sausage 10.99 French Toast (Made with our fresh baked Egg Bread) 8.99 Coffee or Decaf 2.49 Milk Small 1.99 Large 3.49 Cinnamon Roll or Cinnamon Toast 2.99 Iced Tea/Lemonade 2.49 Chocolate Milk Small 1.99 Large 3.49 Oatmeal, Granola, Assorted Cereal & Milk 3.99 Herbal Hot Tea 2.69 *Milk Shakes or Malts (Hand-Dipped) 4.49 Established Add Banana Slices 1.49 Coke, Diet Coke, Sprite, Dr. Pepper Hot Chocolate 2.49 Breads: 1996 & Mello Yello 2.49 New York Egg Cream 2.99 Rye Pumpernickel Dr. Brown Assorted Sodas 2.99 (Milk, Seltzer & Chocolate Syrup) Wheat Boylan’s Bottle Soda 2.99 Bottled Water .99 Oatmeal Marble Rye Eggs & Omelettes Available *Milk Shake & Ice Cream Flavors: Vanilla, Chocolate, Strawberry Sourdough only until All eggs served with Silver Dollar Potato Cakes and your choice of Toast or Bagel. -

2008 Main Newsletter

cŠqa BERESHITH "IN THE BEGINNING" A Newsletter for Beginners, by Beginners ziy`xa Vol. XXI No. 3 Nissan 5768/April 2008 PESACH NOSTALGIA Rabbi Avi Billet When I think of Passover (Pesach), the most vivid memories I have are about turning the house over in preparation for the family seder and the role my grandparents would play leading up to that exciting evening. They always spent the holiday with us and would often come a few days in advance of the holiday to help with the cleaning and cooking. And of course, they looked forward to spending quality time with us, their grandkids. My grandmother would chase us around the house helping us clean (and probably wound up doing most of the cleaning herself). Most of her time, however, was spent preparing goodies that conform to the holiday rules of no chametz (leaven - flour and water). I really thought she had invented potato starch and matzo meal. She made rolls and honey cookies and muffins and noodles. And she used eggs -- boy did she use eggs! From her classic “grammy-eggs” and matzah brei, to her noodles for the chicken soup, to the crepe-like omelettes that became the out- side of her famous cheese blintzes. Many of my memories of those days are colored yellow. Grammy doesn’t do too much cooking now, but we still give her credit for all the delicacies we have grown accustomed to eating on Passover. My grandfather also had an important role in the kitchen, though his creativity was limited to the things he made best: (cont. -

Download Itinerary

London to Paris Cycle UK & FRANCE Activity: Cycle Grade: 1 Challenging Duration: 5 Days ycling from London to Paris is one of strenuous hill-climbs, the sight of the Eif- CHALLENGE GRADING Cthe great cycle experiences in Europe. fel Tower, our finishing point, will evoke a Passing through picturesque Kent coun- real sense of achievement. Our trips are graded from Challenging (Grade 1) to tryside, we cross the Channel and con- Extreme (Grade 5). tinue through the small villages and me- Our last day in Paris allows us to explore This ride is graded Challenging (1). Main chal- dieval market towns of Northern France. the sights and soak up the romantic at- lenges lie in the long distances (70-100 miles) With long days in the saddle and some mosphere of this majestic city! with undulating terrain, including some short, sharp climbs. Many factors influence the Challenge Grading, such as terrain, distances, climate, altitude, living conditions, etc. The grade reflects the overall trip; This was my first time on a Discover Adventure trip, and I’m some sections will feel more challenging than “ others. Unusual weather conditions also have a sure it won’t be my last! - Helen significant impact, and not all people are tested by the same aspects. Our grading levels are intended as a guide, but span a broad spectrum; trips within the same grade will still vary in the level of challenge provided. DETAILED ITINERARY Day 1: London – Dover – Dunkirk An early start allows us to avoid the morning traffic as we pass through the outskirts of London onto quieter roads. -

Brooklyn-Queens Greenway Guide

TABLE OF CONTENTS The Brooklyn-Queens Greenway Guide INTRODUCTION . .2 1 CONEY ISLAND . .3 2 OCEAN PARKWAY . .11 3 PROSPECT PARK . .16 4 EASTERN PARKWAY . .22 5 HIGHLAND PARK/RIDGEWOOD RESERVOIR . .29 6 FOREST PARK . .36 7 FLUSHING MEADOWS CORONA PARK . .42 8 KISSENA-CUNNINGHAM CORRIDOR . .54 9 ALLEY POND PARK TO FORT TOTTEN . .61 CONCLUSION . .70 GREENWAY SIGNAGE . .71 BIKE SHOPS . .73 2 The Brooklyn-Queens Greenway System ntroduction New York City Department of Parks & Recreation (Parks) works closely with The Brooklyn-Queens the Departments of Transportation Greenway (BQG) is a 40- and City Planning on the planning mile, continuous pedestrian and implementation of the City’s and cyclist route from Greenway Network. Parks has juris- Coney Island in Brooklyn to diction and maintains over 100 miles Fort Totten, on the Long of greenways for commuting and Island Sound, in Queens. recreational use, and continues to I plan, design, and construct additional The Brooklyn-Queens Greenway pro- greenway segments in each borough, vides an active and engaging way of utilizing City capital funds and a exploring these two lively and diverse number of federal transportation boroughs. The BQG presents the grants. cyclist or pedestrian with a wide range of amenities, cultural offerings, In 1987, the Neighborhood Open and urban experiences—linking 13 Space Coalition spearheaded the parks, two botanical gardens, the New concept of the Brooklyn-Queens York Aquarium, the Brooklyn Greenway, building on the work of Museum, the New York Hall of Frederick Law Olmsted, Calvert Vaux, Science, two environmental education and Robert Moses in their creations of centers, four lakes, and numerous the great parkways and parks of ethnic and historic neighborhoods. -

Gagosian Gallery

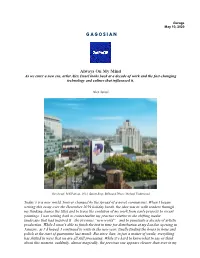

Garage May 10, 2020 GAGOSIAN Always On My Mind As we enter a new era, artist Alex Israel looks back at a decade of work and the fast-changing technology and culture that influenced it. Alex Israel Alex Israel, Self-Portrait, 2013, Sunset Strip, Billboard Photo: Michael Underwood Today’s is a new world, forever changed by the spread of a novel coronavirus. When I began writing this essay over the December 2019 holiday break, the idea was to walk readers through my thinking (hence the title) and to trace the evolution of my work from early projects to recent paintings. I was writing both to contextualize my practice relative to the shifting media landscape that had inspired it—the previous “new world”—and to punctuate a decade of artistic production. While I wasn’t able to finish the text in time for distribution at my London opening in January, as I’d hoped, I continued to write in the new year, finally finding the hours to hone and polish at the start of quarantine last month. But since then, in just a matter of weeks, everything has shifted in ways that we are all still processing. While it’s hard to know what to say or think about this moment, suddenly, almost magically, the previous one appears clearer than ever in my rearview mirror. What used to resemble a living, breathing ecosystem now feels like a time capsule, and whether what happens next is a new chapter, a new book, or (perhaps most likely) a new language altogether, one thing’s for sure: it’s happening. -

Page 1 Jewish Food

Jewish Food - Free Printable Wordsearch SHAMENTASHEN KA HM BRBHUMMUSCH IPSALATAKASHA OEI D LT RPCMATZAHBALLSO UPL Z ELHE HHA BIALY KAR HCCH H ACBC AARCC HAROSET HLAKL EMANISCHEWITZ ELEEV S DLGLGI KU NEIUL IFKJACHNUN AFERD BLGU MATEB BORSCHTBOAG LEPA LEXNE AKP GE AMHIL FTO SEF REY AAHKOL RBAU A PLCOUC ARKR HH PSPH FI AS LHHMR SVI S SEUEAA KYF C HSMRNIT BEE MH AHMPDN ZLTTR AN KOUIE HAIL UCI SNSCHL AHNIS AT HEBKKA LBFTH RZ OYALNM VREZA OE UBE IIAGE LOL KK SNI MN AA H I ME URAV YERUSHALMI SOUP MANDEL BRISKET BLINTZ MATZAH BALL SOUP SHAKSHOUKA JACHNUN LATKE HUMMUSCHIPSALAT SUFGANIYAH FALAFEL KUGEL KOSHER PICKLE SCHNITZEL CHRAIN BABKA CHOPPED LIVER TEIGLACH LEKACH BAGEL MANISCHEWITZ CHAROSET MATZAH HAMIN MANDEL BREAD MACAROON HUMMUS BIALY GEFILTE FISH RUGELACH BOREKA HALVA APPLES HONEY KREPLACH KIBBEH KASHA HAMENTASHEN BORSCHT SABICH KNISH MATZAH BREI CHALLAH FARFEL ARAK LOX Free Printable Wordsearch from LogicLovely.com. Use freely for any use, please give a link or credit if you do. Jewish Food - Free Printable Wordsearch KNISH MA MAKUGELP AN P STI BABKALFALAFEL UZSSG EFILTEFISH FAC CMS LGLHH HAH OAAS NEN O XNTAK IWD N IKBBORSCHT IEE T YEISHCK ZTL YHE ACHU HIEZ BAIB KHH EMOBLS LRGI RBMATZAHBREIM PBHLE LA ER PHUPE AALAL PI IASEH HKECDY LS CM DCDSH AKLEKACHKECHA ROSETLNRHALVA CEBOREKALN JACHNUNAILUO HTK ET MEVGU HAMINAAM PFEK SAUR LRA BLINTZHHCO ANA BEASAFI C ANRA H GARO ERHO LCAN K KOSHER PICKLE SUFGANIYAH FALAFEL LATKE CHOPPED LIVER SCHNITZEL CHRAIN KUGEL MANISCHEWITZ TEIGLACH LEKACH BABKA MANDEL BREAD CHAROSET MATZAH BAGEL GEFILTE FISH MACAROON HUMMUS HAMIN APPLES HONEY RUGELACH BOREKA BIALY HAMENTASHEN KREPLACH KIBBEH HALVA MATZAH BREI BORSCHT SABICH KASHA SOUP MANDEL CHALLAH FARFEL KNISH SHAKSHOUKA BRISKET BLINTZ ARAK JACHNUN LOX Free Printable Wordsearch from LogicLovely.com. -

Jewish Cooking Cookbook

Camp Coleman Jewish Cooking Session 1 2019 Hamentashen Matzah Brei 1 ½ C sugar 1 sheet of matzah 4 c flour 2 tbsp hot water 1 T Baking Powder 1 egg 1/2t salt 2 sticks butter 1 tbsp butter 2 eggs cinnamon 1/4c orange juice powder sugar Filling 1 cups semisweet chocolate chips Break matzah into small pieces and put into bowl 1/3 cup sugar with water. In another bowl, beat the egg with a 1 T butter fork. Melt butter in frying pan over medium heat. 1 T milk Pour egg over matzah then pour into hot pan. 1 tsp vanilla 1 egg Let mixture become golden brown. Flip and cook the other side to golden brown. Sprinkle with Preheat 400 cinnamon and sugar. Enjoy! Ingredients into mixer in order. Cut butter into small pieces and blend in dry ingredients. Then add egg and OJ. Filling Melt chocolate in microwave. Add sugar, butter, milk, and vanilla. Stir, and return to microwave very briefly, just to melt butter. Gradually, stir beaten egg into chocolate. Use this filling immediately before it hardens. Bake 25 mins @400 Oreo Chocolate Cheesecake Israeli Chocolate Balls 24 oreos 7 oz (about 30) graham crackers 8 oz cream cheese (softened) ¾ cup granulated sugar 5 tablespoons unsweetened cocoa powder 1/3 cup sugar 7 tablespoons milk 1 tsp vanilla extract 1 teaspoon vanilla 2 egss, added one at a time 7 tablespoons butter or margarine ¼ cup oreo crumbs ½ teaspoon cinnamon coconut and/or sprinkles 1. Preheat the oven to 350 2. Line a regular sized muffin pan with 12 muffin liners. -

Internet Parsha Sheet on Yisro

and their disconnect from Torah for three days weakened and diminished the BS"D charge of emunah they had recently acquired. The Talmud records that either the prophets that immediately succeeded Moshe, or, as the Rambam (Hilchot Tefillah 12:1) teaches, Moshe himself, instituted that the Torah be To: [email protected] read/taught on Shabbos, Monday, and Thursday so that the Jewish people From: [email protected] will not go three days without Torah. The Tikunei Zohar (Shemos 60a) teaches that Hashem, His Torah, and Israel are one and inseparable. Torah is the great connector. When the Jewish people are connected to Hashem through the Torah, then their emunah can uplift and sustain them. When, however, they are disconnected from Torah, miracles by themselves do not have a long-term effect. INTERNET PARSHA SHEET Case in point; in Kings (I, chapter 19) we read of the miraculous descent of fire orchestrated by Eliyahu haNavi on Mount Carmel. We are taught that the ON YISRO - 5780 many spectators who previously could not decide where their allegiance lay, either to Hashem or to Ba'al, responded to the fire by immediately bursting forth with, "Hashem, He is the G-d, Hashem He is the G-d", and they then [email protected] / www.parsha.net - in our 25th year! To receive this parsha sheet, go slaughtering the four hundred and fifty false prophets of Ba'al. Sadly, they to http://www.parsha.net and click Subscribe or send a blank e-mail to soon returned to their former ways. The exalting effect of miracles dissipates [email protected] Please also copy me at [email protected] A very quickly. -

London to Paris Cycle

LONDON TO PARIS CYCLE UK, FRANCE • CYCLE • YELLOW 3 ABOUT THE CHALLENGE Cycling from London to Paris is one of the great cycle experiences in Europe. Passing through picturesque Kent countryside, we cross the Channel and continue through the small villages and medieval market towns of Northern France. With long days in the saddle and some strenuous hill-climbs, the sight of the Eiffel Tower, our finishing point, will evoke a real sense of achievement. Our last day in Paris allows us to explore the sights and soak up the romantic atmosphere of this majestic city! Don't miss the huge spectacle that is the Tour de France on the July 2019 departure! LONDON TO PARIS CYCLE • 5 DAYS Day 1: London – Dover – Dunkirk An early start allows us to avoid the morning traffic as we pass through the outskirts of London onto quieter roads. It is not long before we are among the rolling fields and villages of rural Kent, passing orchards and traditional oast houses www.discoveradventure.com Tel: +44 (0) 1722 718444 PAGE 2 LONDON TO PARIS CYCLE where hops are stored. We follow country roads across the hills of the North Downs to Dover and the coast. Taking the ferry to Calais, we have dinner on board and cycle the short distance to our hotel. Night hotel. (Dinner on ferry not included) Cycle approx. 136km (85 miles) ROUTE PROFILE Day 2: Dunkirk – Cambrai We head south from Dunkirk, riding roughly parallel to the Belgian border. A long day in the saddle lies ahead, but the terrain is fairly flat as we pass through small villages and farmland, with some areas of shady woodland. -

Hollywood Hills

Celebrity Homes Map Hollywood Hills Guide to Stars in Hollywood Hills ・ 60 Addresses The information contained in this document is exclusive property of StarMap, Inc. You agree that the service StarMap® provides is for informational purposes only and is subject to the Terms & Conditions. Welcome to the Hollywood Hills. If you are coming here to explore the nature of humanity at it’s most upscale, pristine and creative form, you have come to the right place. There are two unique qualities that make Hollywood Hills such a desired destination for celebrities and tourists alike; the terrain and of course the Stars that inhabit the region. The Hollywood Hills are the part of the Santa Monica Mountains, which makes them incredibly, well, hilly. Hills as we know aren’t flat, so they are difficult to build on. This creates for some creative and unique architectural opportunities for folks with dreams, ambition and money; the resources that come in abundance in this area. The Hollywood Hills isn’t your typical neighborhood, you won’t find two houses alike in this region. You won’t find apartment complexes, condo units and other standardized living in this area. Due to the diversity of land formations, each home is different from the next. The diversity of the twenty some odd thousand people that live in this 7 square mile is quite diverse as well. Not everyone that lives in The Hills is a television star or otherwise even some one that’s known. However, reading down the list of notable residents is like reading a list of the Golden Globes nominations — the stars that you’ve grown to love over a lifetime more than likely own a residence here.