Descendants of Sampson Toovey and Katherine Shrimpton of Amersham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weekly List of Planning Consultations 11.03.2021

CONSERVATION CASES PROCESSED BY THE GARDENS TRUST 11.03.2021 This is a list of all the conservation consultations that The Gardens Trust has logged as receiving over the past week, consisting mainly, but not entirely, of planning applications. Cases in England are prefixed by ‘E’ and cases in Wales with ‘W’. When assessing this list to see which cases CGTs may wish to engage with, it should be remembered that the GT will only be looking at a very small minority. SITE COUNTY SENT BY REFERENCE GT REF DATE GR PROPOSAL RESPONSE RECEIVED AD BY E ENGLAND Ashton Court Avon North 21/P/0510/FUL www.n- E20/1806 08/03/2021 II* PLANNING APPLICATION 30/03/2021 Somerset somerset.gov.uk/lookatpl Conversion of Pavilion building, anningapplications incorporating a small extension, lobby, plant room, timber cladding and replacement doors and windows, resin play area and other associated works, to provide temporary classroom accommodation for up to two years by Cathedral Primary School to supplement lost classroom space. Upon termination of the temporary use, the proposed classrooms are proposed for use in perpetuity in connection with the established forest school and sports education at the application site. Provision of purpose-built, self- contained changing room facility and associated works. BUILDING ALTERATION [email protected] dmscanningrequests@n- somerset.gov.uk Benham Park Berkshire West 21/00196/HOUSE E20/1797 05/03/2021 II PLANNING APPLICATION 26/03/2021 Berkshire DC https://publicaccess.west Single storey orangery extension to berks.gov.uk/online- existing dwelling and formation of link applications/search.do?a Benham Gardens, Benham Park, Marsh ction=simple&searchTyp Benham, Newbury e=Application BUILDING ALTERATION [email protected] Ascot Place Berkshire Bracknell 21/00167/FUL E20/1799 05/03/2021 II* PLANNING APPLICATION 26/03/2021 Forest http://www.bracknell- Erection of new timber gates and brick forest.gov.uk/viewplanni piers, following removal of existing ngapplications timber gates. -

13742 the London Gazette, Ist November 1977 Home Office

13742 THE LONDON GAZETTE, IST NOVEMBER 1977 CONSULTATIVE DOCUMENTS Black Notley Parish Council and People. Bleasby, People of COM(77) 483 FINAL Bletchingley Women's Institute. R/2347/77. Commission communication to the Council on Blockley Parish Council. the energy situation in the Community and in the world. Borley, People of Boughton Aluph and Eastwell, People of COMMISSION DOCUMENT DEPOSITED SEPARATELY Boys' Brigade. R/2131/77. Letter of amendment to the preliminary draft Brackley, People of general budget of the European Communities for 1978. Bracknell Development Corporation. Bracknell District Council. COM(77) 467 FINAL Braintree District Council and People. R/2361/77. Report from the Commission to the Council on Braunstone, People of the application to exported products of Council Regula- Breadsall, People of tion (EEC) No. 2967/76 laying down common standards Brighton Corporation. for the water content of frozen and deep-frozen chickens, British Association of Accountants and Auditors. hens and cocks. British Bottlers Institute. British Constitution Defence.Committee (Liverpool). COM(77) 443 FINAL British Dental Association. R/2355/77. Commission communication to the Council on 'British Medical Association. improving co-ordination of national economic policies. British Optical Association. COM(77) 473 FINAL British Railways Board. Bromesberrow Parish Council. R/23 87/77. Report on the opening, allocation and manage- Bromley Corporation. ment of the Community tariff quota in 1977 for frozen Brook, Milford Sandhills, Witley and Wormley, People of beef and veal. Broxtowe District Council. COM(77) 494 FINAL Buckingham Town Council. R/2473/77. Annual Report on the economic situation in the Burnham-on-Sea and Highbridge Town Council. -

Buckinghamshire HEDNA Appendices

Buckinghamshire Housing and Economic Development Needs Assessment 2016 Study Appendices December 2016 Opinion Research Services | The Strand • Swansea • SA1 1AF | 01792 535300 | www.ors.org.uk | [email protected] Opinion Research Services ▪ Atkins | Buckinghamshire HEDNA: Study Appendices December 2016 Opinion Research Services | The Strand, Swansea SA1 1AF Jonathan Lee | David Harrison | Nigel Moore enquiries: 01792 535300 · [email protected] · www.ors.org.uk Atkins | Euston Tower, 286 Euston Road NW1 3AT Richard Ainsley enquiries: 020 7121 2280 · [email protected] · www.atkinsglobal.com © Copyright December 2016 2 Opinion Research Services ▪ Atkins | Buckinghamshire HEDNA: Study Appendices December 2016 Contents Appendix A ......................................................................................................... 4 List of Property Agents Consulted .................................................................................................................. 4 Appendix B ......................................................................................................... 5 Stakeholder workshop meeting notes............................................................................................................ 5 Appendix C ......................................................................................................... 9 Site Reconnaissance ...................................................................................................................................... 9 Appendix D ..................................................................................................... -

Daily Report Monday, 4 February 2019 CONTENTS

Daily Report Monday, 4 February 2019 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 4 February 2019 and the information is correct at the time of publication (07:00 P.M., 04 February 2019). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 7 Cabinet Office: Written ATTORNEY GENERAL 7 Questions 13 Attorney General: Trade Census: Sikhs 13 Associations 7 Cybercrime 14 Crown Prosecution Service: Cybercrime: EU Countries 14 Staff 7 Interserve 14 Crown Prosecution Service: Interserve: Living Wage 15 West Midlands 7 Reducing Regulation Road Traffic Offences: Committee 15 Prosecutions 8 DEFENCE 15 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 9 Arctic: Defence 15 Climate Change Convention 9 Armed Forces: Doctors 15 Companies: National Security 9 Armed Forces: Professional Organisations 16 Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy: Army: Deployment 16 Brexit 10 Army: Officers 16 Energy: Subsidies 10 Chinook Helicopters: Innovation and Science 11 Accidents 17 Insolvency 11 Ecuador: Military Aid 17 Iron and Steel 12 European Fighter Aircraft: Safety Measures 17 Telecommunications: National Security 12 General Electric: Rugby 18 CABINET OFFICE 13 HMS Mersey: English Channel 18 Cabinet Office: Trade Joint Strike Fighter Aircraft: Associations 13 Safety Measures 18 Ministry of Defence: Brexit 19 Ministry of Defence: Public Free School Meals: Newcastle Expenditure 19 Upon Tyne Central 36 Royal Tank -

WYCOMBE DISTRICT COUNCIL Chief Executives / Strategic Management Board (SMB)

WYCOMBE DISTRICT COUNCIL Chief Executives / Strategic Management Board (SMB) Acting Chief Executive PA Manager/ Personal Personal Assistant to Assistant to the Chief Executive John East Leader and Cabinet [email protected] PA to Heads of Service Interim Corporate Director (Growth and R egeneration) John East Head of Head of Head of Head of Housing, Head of Interim Head of Major Projects Democratic, Finance HR, ICT and Environment Planning Regeneration and Legal and and Facilities and Community and and Estates Policy Services Commercial Management Services Sustainability Investment Executive Catherine David John Nigel Penelope Peter Charles Wright Whitehead Skinner McMillan Dicker Tollitt Brocklehurst catherine.whitehead@ david.skinner@ john.mcmillan@ nigel.dicker@ penelope.tollitt@ peter.wright@ charles.brocklehurst@ wycombe.gov.uk wycombe.gov.uk wycombe.gov.uk wycombe.gov.uk wycombe.gov.uk wycombe.gov.uk wycombe.gov.uk WYCOMBE DISTRICT COUNCIL Democratic, Legal and Policy Services Head of Democratic, Personal Assistant to Head of Democratic, Legal and Legal and Policy Services Policy Services and Catherine Whitehead Head of Finance and Commercial [email protected] Communications District Lawyer Democratic and and Services Improvement Manager Legal Services Manager Manager Catherine Jenny Ian Spalton Caprio Hunt [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Communications Property Electoral Services/ Data and Feedback Planning Land Charges Management Contracts and Litigation -

Evidence on Aluminium Collection by Local Authorities Project Code

Project Name: Evidence on Aluminium Collection by Local Authorities Project Code - WR1201 Final Report April 2008 This research was commissioned and funded by Defra. The views expressed reflect the research findings and the author’s interpretation. The inclusion of or reference to any particular policy in this report should not be taken to imply that it has, or will be, endorsed by Defra. BeEnvironmental Ltd · Suite 213 Lomeshaye Business Village · Turner Road · Nelson · Lancashire · BB9 7DR · 01282 618135 · www.beenvironmental.com Quality Control Job Evidence on Aluminium Collection by Local Authorities Client Defra Date April 2008 Report Title Evidence on Aluminium Collection by Local Authorities (Project Code: WR1201) Report status Final Author Dr Jane Beasley Director Reviewed by Elaine Lockley Director Client Contact Nick Blakey, Waste Evidence Branch, Defra Details Be Environmental Suite 213 Lomeshaye Business Village Turner Road, Nelson Lancashire, BB9 7DR Phone 01282 618135 Fax 01282 611416 [email protected] Disclaimer: BeEnvironmental (the trading name of BeEnvironmental Limited) has taken all reasonable care and diligence in the preparation of this report to ensure that all facts and analysis presented are as accurate as possible within the scope of the project. However no guarantee is provided in respect of the information presented, and BeEnvironmental is not responsible for decisions or actions taken on the basis of the content of this report. BeEnvironmental Ltd · Suite 213 Lomeshaye Business Village · Turner Road -

2004 No. 3211 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2004 No. 3211 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The Local Authorities (Categorisation) (England) (No. 2) Order 2004 Made - - - - 6th December 2004 Laid before Parliament 10th December 2004 Coming into force - - 31st December 2004 The First Secretary of State, having received a report from the Audit Commission(a) produced under section 99(1) of the Local Government Act 2003(b), in exercise of the powers conferred upon him by section 99(4) of that Act, hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and application 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the Local Authorities (Categorisation) (England) (No.2) Order 2004 and shall come into force on 31st December 2004. (2) This Order applies in relation to English local authorities(c). Categorisation report 2. The English local authorities, to which the report of the Audit Commission dated 8th November 2004 relates, are, by this Order, categorised in accordance with their categorisation in that report. Excellent authorities 3. The local authorities listed in Schedule 1 to this Order are categorised as excellent. Good authorities 4. The local authorities listed in Schedule 2 to this Order are categorised as good. Fair authorities 5. The local authorities listed in Schedule 3 to this Order are categorised as fair. (a) For the definition of “the Audit Commission”, see section 99(7) of the Local Government Act 2003. (b) 2003 c.26. The report of the Audit Commission consists of a letter from the Chief Executive of the Audit Commission to the Minister for Local and Regional Government dated 8th November 2004 with the attached list of local authorities categorised by the Audit Commission as of that date. -

Chiltern District Revitalisation Groups

CHILTERN DISTRICT REVITALISATION GROUPS David Gardner Active Communities Officer Chiltern District Council & South Bucks District Council Email: [email protected] REVITALISATION ? A working definition: “Communities where progress is celebrated and self-improvement embraced” Chiltern District Revitalisation Groups Amersham Action Group Amersham Old Town Community Revitalisation Group Chalfont St Giles & Jordans Revitalisation Committee Chalfont St Peter Revitalisation Action Group Chesham Connect Little Chalfont Community Association Great Missenden & Prestwood Revitalisation Group Why do these group require our support? • the community identifies its own needs, values, challenges and priorities partners & community wide representation Retailers & businesses youth clubs older people action group conservation , environment & transition groups local community led services & amenities (eg library) Chiltern District Council Bucks County Council Town /parish council faith groups Police Buckinghamshire NHS Revitalisation Groups & Their Key Objectives Viability & vitality of town & village centres Environmental improvements for residents and visitors Demand effective statutory services Community led provision of services Health & wellbeing projects - younger & older people Shared Strategic Priorities ? • Promote healthy living • Promote wellbeing & address health inequalities • Promote community safety • Build capacity in voluntary sector • Support the development & inclusion of younger people • Promote community cohesion • Conserve the -

Knives Farm 150 Wycombe Road Prestwood Buckinghamshire Hp16 0Hj

KNIVES FARM 150 WYCOMBE ROAD PRESTWOOD BUCKINGHAMSHIRE HP16 0HJ DESCRIPTION Knives Farm is a lovely, Grade II listed farmhouse situated on the fringes of this popular Chiltern village. The accommodation is arranged over three floors with period features throughout including wood paneling, inglenook fireplaces, wall and ceiling beams. The house has evolved over many years, resulting in accommodation which flows well with bright, spacious rooms, wood burning stoves in the reception areas and an AGA in the kitchen. However, there is still plenty of scope for updating and to enable the buyer to put their own stamp on it. There is additional accommodation in the form of a self contained, two bedroomed flat over the triple garage block with access via an external staircase and across a roof terrace. Outside, the formal gardens extend to just over half an acre and are divided into two distinct areas with a colourful, landscaped garden behind the kitchen with an ornamental fish pond and lawns leading down to the paddock beyond. The front is well screened with mature hedges and specimen trees, being level and mainly to lawn. The large driveway offers ample parking leading to the triple garage. Additionally, the property benefits from a one and a half acre paddock to the rear of the property that overlooks the open fields and countryside beyond. Price…£1,250,000 Freehold _____________________________________________________________ AMENITIES Prestwood village centre has an excellent range of day to day facilities available including a variety of local shops, ie Butchers, Bakers, Newsagents, Post Office, Chemist, Florist and Supermarkets, together with Doctors' and Dentists' surgeries. -

A Report Produced for Department of the Environment Transport and The

Final Identifying the Options Available for Determining Population Data and Identifying Agglomerations in Connection with EU Proposals Regarding Environmental Noise A report produced for Department of the Environment Transport and the Regions, The Scottish Executive, The National Assembly for Wales and Department of Environment for Northern Ireland Katie King Tony Bush January 2001 Final Identifying the Options Available for Determining Population Data and Identifying Agglomerations in Connection with EU Proposals Regarding Environmental Noise A report produced for Department of the Environment Transport and the Regions, The Scottish Executive, The National Assembly for Wales and Department of Environment for Northern Ireland Katie King Tony Bush January 2001 Final Title Identifying the Options Available for Determining Population Data and Identifying Agglomerations in Connection with EU Proposals Regarding Environmental Noise Customer Department of the Environment Transport and the Regions, The Scottish Executive, The National Assembly for Wales and Department of Environment for Northern Ireland Customer reference Confidentiality, copyright and reproduction File reference \\151.182.168.37\kk\noise\ed50035\final report\final report 15-2.doc Report number AEAT/ENV/R/0461 (Final) Report status Final AEA Technology E5 Culham Abingdon Oxfordshire, OX14 3ED Telephone 01235 463715 Facsimile 01235 463574 AEA Technology is the trading name of AEA Technology plc AEA Technology is certificated to BS EN ISO9001:(1994) Name Signature Date Author Katie King Tony Bush Reviewed by Tony Bush Approved by John Stedman The maps included in this report have been generated by AEA Technology using OS maps on behalf of DETR with permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of The Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office, © Crown copyright. -

Chiltern Councillor Update Economic Profile of Asheridge Vale & Lowndes Ward

Chiltern Councillor Update Economic Profile of Asheridge Vale & Lowndes Ward April 2014 Produced by Buckinghamshire Business First’s research department P a g e | 2 1.0 Introduction Asheridge Vale & Lowndes is home to 4,850 people and provides 1,000 jobs in 82 businesses. Of these businesses, 33 (40.2 per cent) are Buckinghamshire Business First members. There were 3,438 employed people aged 16-74 living in Ash ridge Vale & Lowndes ward at the 2011 Census, 256 more than the 3,182 recorded in 2001. Over that period the working age population rose 195 to 2,996 while the total population rose 351 to 4,850. The number of households rose by 207 (12.1 per cent) to 1,919. This is the highest percentage increase out of all wards in Chiltern. Based on the increase in number of households, the ward ranks 16th out of all wards in Buckinghamshire. The largest companies in Asheridge Vale & Lowndes include: Axwell Wireless; Broadway Bowls Club; Chesham Park Community College; Survex Ltd; Draycast Foundries Ltd; Elmtree Country First School; and Martec Europe Ltd. There are 63 Asheridge Vale & Lowndes, representing 2.2 per cent of working age residents, including 30 claimants aged 25-49 and 15 who have been claiming for more than twelve months. Superfast broadband is expected to be available to 98 per cent of premises in the Asheridge Vale & Lowndes ward by March 2016 with commercial providers responsible for the full 98 per cent. The Connected Counties project, run by BBF, will deliver nothing to this particular ward due to the high proportion of fibre availability through commercial providers. -

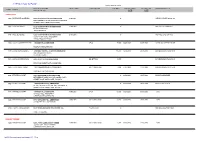

LDP Summary by Parish Chiltern & South Bucks

LDP Summary by Parish Chiltern & South Bucks SCHEME-LOCATION TARGET-DATE CONTRACTOR ESTIMATE ACTUAL START ACTUAL END SPONSOR-OFFICER CRNO GROUP SCHEME-DETAIL DATE DATE AMERSHAM 2846 DEVELOPER SCHEMES U292 STATION APPROACH AMERSHAM 28/03/2007 0 GERRY HARVEY 01296 382660 IRON HORSE STATION APPROACH AMERSHAM - ALTERATION TO EXISTING ACCESS 3469 HAUC SCHEMES U202 PLANTATION ROAD AMERSHAM 11/08/2008 0 MICHAEL CHILTON 6612 PLANTATION ROAD MAINS RENEWAL 3418 HAUC SCHEMES U202 PLANTATION ROAD AMERSHAM 28/07/2008 0 MICHAEL CHILTON 6612 PLANTATION ROAD, AMERSHAM THREE VALLEYS WATER 3363 LOCAL COMMITEE DELEG STANLEY HILL AMERSHAM JPCS 17,000 30/06/2008 03/07/2008 CHRIS SCHWIER 01494 586622 FOOTWAY RESURFACING 3231 LOCAL MAINTENANCE VARIOUS ROUTES - CHILTERN AMERSHAM 105,490 12/05/2008 20/05/2008 DAVID BROWN 01494 586608 AMERSHAM GC2C AREA PATCHING GANG 2 3191 LOCAL MAINTENANCE A416 STATION ROAD AMERSHAM BB JETTING 5,000 DAVID BROWN 01494 586608 DRAINAGE INVESTIGATION / REPAIRS 3193 LOCAL MAINTENANCE ST LEONARDS ROAD CHESHAM BOIS MILES MACADAM 7,000 27/05/2008 27/05/2008 DAVID BROWN 01494 586608 CARRIAGEWAY SURFACING 3159 STRATEGIC MAINT A413 AMERSHAM ROAD AMERSHAM 0 01/04/2008 30/05/2008 PHIL STONEHEWER BETWEEN STANLEY HILL AND COKES LANE - LC5 TO LC47 STREET LIGHT SWITCH OFF - PHASE 2 3158 STRATEGIC MAINT AMERSHAM BYPASS AMERSHAM 0 01/04/2008 30/05/2008 PHIL STONEHEWER BETWEEN WHIELDEN LANE RBT AND GORE HILL RBT - LC40 TO LC53 STREET LIGHT SWITCH OFF - PHASE 2 3444 STRATEGIC MAINT STANLEY HILL AMERSHAM 30/06/2008 JPCS 13,000 30/06/2008 03/07/2008