Boko Haram's Religious and Political Worldview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISIS in Africa: Implications from Syria and Iraq Dr

ISIS in Africa: Implications from Syria and Iraq Dr. Joseph Siegle28 Africa Center for Strategic Studies National Defense University At the end of 2016, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, leader of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), announced that the group had “expanded and shifted some of our command, media, and wealth to Africa.” ISIS’s Dabiq magazine referred to the regions of Africa that were part of its “caliphate:” “the region that includes Sudan, Chad and Egypt has been named the caliphate province of Alkinaana; the region that includes Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, Kenya and Uganda as the province of Habasha; the North African region encompassing Libya, Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, Nigeria, Niger and Mauritania as Maghreb, the province of the caliphate.” Leaving aside the mismatched ethno-linguistic groupings included in each of these “provinces,” ISIS’s interest in establishing a presence in Africa has long been a part of its vision for a global caliphate. Battlefield setbacks in ISIS’s strongholds in Iraq and Syria since 2015, however, raise questions of what impact this will have for ISIS’s African aspirations. A useful starting point in considering this question is to recognize that the threat from violent Islamist groups in Africa is not monolithic but is comprised of a variety of distinct entities. For the most part, these groups are geographically concentrated and focused on local territorial or political objectives. Specifically, the Africa Center for Strategic Studies has identified 5 major categories of militant Islamists groups in Africa (see map): http://africacenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Africas-Active-Militant-Islamist- Groups-November-2016.pdf. -

BOKO HARAM Emerging Threat to the U.S

112TH CONGRESS COMMITTEE " COMMITTEE PRINT ! 1st Session PRINT 112–B BOKO HARAM Emerging Threat to the U.S. Homeland SUBCOMMITTEE ON COUNTERTERRORISM AND INTELLIGENCE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES December 2011 FIRST SESSION U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 71–725 PDF WASHINGTON : 2011 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman LAMAR SMITH, Texas BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California LORETTA SANCHEZ, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas HENRY CUELLAR, Texas GUS M. BILIRAKIS, Florida YVETTE D. CLARKE, New York PAUL C. BROUN, Georgia LAURA RICHARDSON, California CANDICE S. MILLER, Michigan DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois TIM WALBERG, Michigan BRIAN HIGGINS, New York CHIP CRAVAACK, Minnesota JACKIE SPEIER, California JOE WALSH, Illinois CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana PATRICK MEEHAN, Pennsylvania HANSEN CLARKE, Michigan BEN QUAYLE, Arizona WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts SCOTT RIGELL, Virginia KATHLEEN C. HOCHUL, New York BILLY LONG, Missouri VACANCY JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas MO BROOKS, Alabama MICHAEL J. RUSSELL, Staff Director & Chief Counsel KERRY ANN WATKINS, Senior Policy Director MICHAEL S. TWINCHEK, Chief Clerk I. LANIER AVANT, Minority Staff Director (II) C O N T E N T S BOKO HARAM EMERGING THREAT TO THE U.S. HOMELAND I. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 II. Findings .............................................................................................................. -

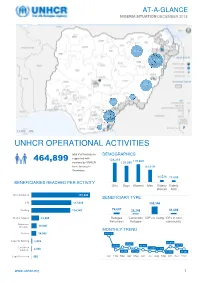

Unhcr Operational Activities 464,899

AT-A-GLANCE NIGERIA SITUATION DECEMBER 2018 28,280 388,208 20,163 1,770 4,985 18.212 177 Bénéficiaires Reached UNHCR OPERATIONAL ACTIVITIES total # of individuals DEMOGRAPHICS supported with 464,899 128,318 119,669 services by UNHCR 109,080 from January to 81,619 December; 34,825 of them from Mar-Apr 14,526 11,688 2018 BENEFICIARIES REACHED PER ACTIVITY Girls Boys Women Men Elderly Elderly Women Men Documentation 172,800 BENEFICIARY TYPE CRI 117,838 308,346 Profiling 114,747 76,607 28,248 51,698 Shelter Support 22,905 Refugee Cameroon IDPs in Camp IDPs in host Returnees Refugee community Awareness Raising 16,000 MONTHLY TREND Referral 14,956 140,116 Capacity Building 2,939 49,819 39,694 24,760 25,441 34,711 Livelihood 11,490 11,158 Support 2,048 46,139 37,118 13,770 30,683 Legal Protection 666 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec www.unhcr.org 1 NIGERIA SITUATION AT-A-GLANCE / DEC 2018 CORE UNHCR INTERVENTIONS IN NIGERIA UNHCR Nigeria strategy is based on the premise that the government of Nigeria assumes the primary responsibility to provide protection and assistance to persons of concern. By building and reinforcing self-protection mechanisms, UNHCR empowers persons of concern to claim their rights and to participate in decision-making, including with national and local authorities, and with humanitarian actors. The overall aim of UNHCR Nigeria interventions is to prioritize and address the most serious human rights violations, including the right to life and security of persons. -

Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’S Enduring Insurgency

Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’s Enduring Insurgency Editor: Jacob Zenn Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’s Enduring Insurgency Jacob Zenn (Editor) Abdulbasit Kassim Elizabeth Pearson Atta Barkindo Idayat Hassan Zacharias Pieri Omar Mahmoud Combating Terrorism Center at West Point United States Military Academy www.ctc.usma.edu The views expressed in this report are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of the Combating Terrorism Center, United States Military Academy, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government. May 2018 Cover Photo: A group of Boko Haram fighters line up in this still taken from a propaganda video dated March 31, 2016. COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Director The editor thanks colleagues at the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point (CTC), all of whom supported this endeavor by proposing the idea to carry out a LTC Bryan Price, Ph.D. report on Boko Haram and working with the editor and contributors to see the Deputy Director project to its rightful end. In this regard, I thank especially Brian Dodwell, Dan- iel Milton, Jason Warner, Kristina Hummel, and Larisa Baste, who all directly Brian Dodwell collaborated on the report. I also thank the two peer reviewers, Brandon Kend- hammer and Matthew Page, for their input and valuable feedback without which Research Director we could not have completed this project up to such a high standard. There were Dr. Daniel Milton numerous other leaders and experts at the CTC who assisted with this project behind-the-scenes, and I thank them, too. Distinguished Chair Most importantly, we would like to dedicate this volume to all those whose lives LTG (Ret) Dell Dailey have been afected by conflict and to those who have devoted their lives to seeking Class of 1987 Senior Fellow peace and justice. -

Breaking Boko Haram and Ramping up Recovery: US-Lake Chad Region 2013-2016

From Pariah to Partner: The US Integrated Reform Mission in Burma, 2009 to 2015 Breaking Boko Haram and Ramping Up Recovery Making Peace Possible US Engagement in the Lake Chad Region 2301 Constitution Avenue NW 2013 to 2016 Washington, DC 20037 202.457.1700 Beth Ellen Cole, Alexa Courtney, www.USIP.org Making Peace Possible Erica Kaster, and Noah Sheinbaum @usip 2 Looking for Justice ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This case study is the product of an extensive nine- month study that included a detailed literature review, stakeholder consultations in and outside of government, workshops, and a senior validation session. The project team is humbled by the commitment and sacrifices made by the men and women who serve the United States and its interests at home and abroad in some of the most challenging environments imaginable, furthering the national security objectives discussed herein. This project owes a significant debt of gratitude to all those who contributed to the case study process by recommending literature, participating in workshops, sharing reflections in interviews, and offering feedback on drafts of this docu- ment. The stories and lessons described in this document are dedicated to them. Thank you to the leadership of the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) and its Center for Applied Conflict Transformation for supporting this study. Special thanks also to the US Agency for International Development (USAID) Office of Transition Initiatives (USAID/OTI) for assisting with the production of various maps and graphics within this report. Any errors or omis- sions are the responsibility of the authors alone. ABOUT THE AUTHORS This case study was produced by a team led by Beth ABOUT THE INSTITUTE Ellen Cole, special adviser for violent extremism, conflict, and fragility at USIP, with Alexa Courtney, Erica Kaster, The United States Institute of Peace is an independent, nonpartisan and Noah Sheinbaum of Frontier Design Group. -

Lessons from Colombia for Curtailing the Boko Haram Insurgency in Nigeria

Lessons From Colombia For Curtailing The Boko Haram Insurgency In Nigeria BY AFEIKHENA JEROME igeria is a highly complex and ethnically diverse country, with over 400 ethnic groups. This diversity is played out in the way the country is bifurcated along the lines of reli- Ngion, language, culture, ethnicity and regional identity. The population of about 178.5 million people in 2014 is made up of Christians and Muslims in equal measures of about 50 percent each, but including many who embrace traditional religions as well. The country has continued to experience serious and violent ethno-communal conflicts since independence in 1960, including the bloody and deadly thirty month fratricidal Civil War (also known as the Nigerian-Biafran war, 1967-70) when the eastern region of Biafra declared its seces- sion and which claimed more than one million lives. The most prominent of these conflicts recently pitch Muslims against Christians in a dangerous convergence of religion, ethnicity and politics. The first and most dramatic eruption in a series of recent religious disturbances was the Maitatsine uprising in Kano in December 1980, in which about 4,177 died. While the exact number of conflicts in Nigeria is unknown, because of a lack of reliable sta- tistical data, it is estimated that about 40 percent of all conflicts have taken place since the coun- try’s return to civilian rule in 1999.1 The increasing wave of violent conflicts across Nigeria under the current democratic regime is no doubt partly a direct consequence of the activities of ethno- communal groups seeking self-determination in their “homelands,” and of their surrogate ethnic militias that have assumed prominence since the last quarter of 2000. -

Othering Terrorism: a Rhetorical Strategy of Strategic Labeling

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 13 Issue 2 Rethinking Genocide, Mass Atrocities, and Political Violence in Africa: New Directions, Article 9 New Inquiries, and Global Perspectives 6-2019 Othering Terrorism: A Rhetorical Strategy of Strategic Labeling Michael Loadenthal Miami University of Oxford Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation Loadenthal, Michael (2019) "Othering Terrorism: A Rhetorical Strategy of Strategic Labeling," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 13: Iss. 2: 74-105. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.13.2.1704 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol13/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Othering Terrorism: A Rhetorical Strategy of Strategic Labeling Michael Loadenthal Miami University of Oxford Oxford, Ohio, USA Reel Bad Africans1 & the Cinema of Terrorism Throughout Ridley Scott’s 2002 film Black Hawk Down, Orientalist “othering” abounds, mirroring the simplistic political narrative of the film at large. In this tired script, we (the West) are fighting to help them (the East Africans) escape the grip of warlordism, tribalism, and failed states through the deployment of brute counterinsurgency and policing strategies. In the film, the US soldiers enter the hostile zone of Mogadishu, Somalia, while attempting to arrest the very militia leaders thought to be benefitting from the disorder of armed conflict. -

An Analysis of What Works and What Doesn't

Radicalisation and Deradicalisation in Nigeria: An Analysis of What Works and What Doesn’t Nasir Abubakar Daniya i Radicalisation and Deradicalisation in Nigeria: An Analysis of What Works and What Doesn’t. Nasir Abubakar Daniya Student Number: 13052246 A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of Requirements for award of: Professional Doctorate Degree in Policing Security and Community Safety London Metropolitan University Faculty of Social Science and Humanities March 2021 Thesis word count: 104, 482 ii Abstract Since Nigeria’s independence from Britain in 1960, the country has made some progress while also facing some significant socio-economic challenges. Despite being one of the largest producers of oil in the world, in 2018 and 2019, the Brooking Institution and World Poverty Clock respectively ranked Nigeria amongst top three countries with extreme poverty in the World. Muslims from the north and Christians from the south dominate the country; each part has its peculiar problem. There have been series of agitations by the militants from the south to break the country due to unfair treatments by the Nigerian government. They produced multiple violent groups that killed people and destroyed properties and oil facilities. In the North, an insurgent group called Boko Haram emerges in 2009; they advocated for the establishment of an Islamic state that started with warning that, western education is prohibited. Reports say the group caused death of around 100,000 and displaced over 2 million people. As such, Niger Delta Militancy and Boko Haram Insurgency have been major challenges being faced by Nigeria for about a decade. To address such challenges, the Nigerian government introduced separate counterinsurgency interventions called Presidential Amnesty Program (PAP) and Operation Safe Corridor (OSC) in 2009 and 2016 respectively, which are both aimed at curtailing Militancy and Insurgency respectively. -

Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances

SWP Research Paper Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber (Eds.) Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances RP 5 June 2015 Berlin All rights reserved. © Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2015 SWP Research Papers are peer reviewed by senior researchers and the execu- tive board of the Institute. They express exclusively the personal views of the authors. SWP Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Ludwigkirchplatz 34 10719 Berlin Germany Phone +49 30 880 07-0 Fax +49 30 880 07-100 www.swp-berlin.org [email protected] ISSN 1863-1053 Translation by Meredith Dale (Updated English version of SWP-Studie 7/2015) Table of Contents 5 Problems and Recommendations 7 Jihadism in Africa: An Introduction Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 13 Al-Shabaab: Youth without God Annette Weber 31 Libya: A Jihadist Growth Market Wolfram Lacher 51 Going “Glocal”: Jihadism in Algeria and Tunisia Isabelle Werenfels 69 Spreading Local Roots: AQIM and Its Offshoots in the Sahara Wolfram Lacher and Guido Steinberg 85 Boko Haram: Threat to Nigeria and Its Northern Neighbours Moritz Hütte, Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 99 Conclusions and Recommendations Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 103 Appendix 103 Abbreviations 104 The Authors Problems and Recommendations Jihadism in Africa: Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances The transnational terrorism of the twenty-first century feeds on local and regional conflicts, without which most terrorist groups would never have appeared in the first place. That is the case in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Syria and Iraq, as well as in North and West Africa and the Horn of Africa. -

Sunni Suicide Attacks and Sectarian Violence

Terrorism and Political Violence ISSN: 0954-6553 (Print) 1556-1836 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ftpv20 Sunni Suicide Attacks and Sectarian Violence Seung-Whan Choi & Benjamin Acosta To cite this article: Seung-Whan Choi & Benjamin Acosta (2018): Sunni Suicide Attacks and Sectarian Violence, Terrorism and Political Violence, DOI: 10.1080/09546553.2018.1472585 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2018.1472585 Published online: 13 Jun 2018. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ftpv20 TERRORISM AND POLITICAL VIOLENCE https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2018.1472585 Sunni Suicide Attacks and Sectarian Violence Seung-Whan Choi c and Benjamin Acosta a,b aInterdisciplinary Center Herzliya, Herzliya, Israel; bInternational Institute for Counter-Terrorism, Herzliya, Israel; cPolitical Science, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA ABSTRACT KEY WORDS Although fundamentalist Sunni Muslims have committed more than Suicide attacks; sectarian 85% of all suicide attacks, empirical research has yet to examine how violence; Sunni militants; internal sectarian conflicts in the Islamic world have fueled the most jihad; internal conflict dangerous form of political violence. We contend that fundamentalist Sunni Muslims employ suicide attacks as a political tool in sectarian violence and this targeting dynamic marks a central facet of the phenomenon today. We conduct a large-n analysis, evaluating an original dataset of 6,224 suicide attacks during the period of 1980 through 2016. A series of logistic regression analyses at the incidence level shows that, ceteris paribus, sectarian violence between Sunni Muslims and non-Sunni Muslims emerges as a substantive, signifi- cant, and positive predictor of suicide attacks. -

Volume 7: Shaping Global Islamic Discourses : the Role of Al-Azhar, Al-Medina and Al-Mustafa Masooda Bano Editor

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eCommons@AKU eCommons@AKU Exploring Muslim Contexts ISMC Series 3-2015 Volume 7: Shaping Global Islamic Discourses : The Role of al-Azhar, al-Medina and al-Mustafa Masooda Bano Editor Keiko Sakurai Editor Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/uk_ismc_series_emc Recommended Citation Bano, M. , Sakurai, K. (Eds.). (2015). Volume 7: Shaping Global Islamic Discourses : The Role of al-Azhar, al-Medina and al-Mustafa Vol. 7, p. 242. Available at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/uk_ismc_series_emc/9 Shaping Global Islamic Discourses Exploring Muslim Contexts Series Editor: Farouk Topan Books in the series include Development Models in Muslim Contexts: Chinese, “Islamic” and Neo-liberal Alternatives Edited by Robert Springborg The Challenge of Pluralism: Paradigms from Muslim Contexts Edited by Abdou Filali-Ansary and Sikeena Karmali Ahmed Ethnographies of Islam: Ritual Performances and Everyday Practices Edited by Badouin Dupret, Thomas Pierret, Paulo Pinto and Kathryn Spellman-Poots Cosmopolitanisms in Muslim Contexts: Perspectives from the Past Edited by Derryl MacLean and Sikeena Karmali Ahmed Genealogy and Knowledge in Muslim Societies: Understanding the Past Edited by Sarah Bowen Savant and Helena de Felipe Contemporary Islamic Law in Indonesia: Shariah and Legal Pluralism Arskal Salim Shaping Global Islamic Discourses: The Role of al-Azhar, al-Medina and al-Mustafa Edited by Masooda Bano and Keiko Sakurai www.euppublishing.com/series/ecmc -

Nigeria Update to the IMB Nigeria

Progress in Polio Eradication Initiative in Nigeria: Challenges and Mitigation Strategies 16th Independent Monitoring Board Meeting 1 November 2017 London 0 Outline 1. Epidemiology 2. Challenges and Mitigation strategies SIAs Surveillance Routine Immunization 3. Summary and way forward 1 Epidemiology 2 Polio Viruses in Nigeria, 2015-2017 Past 24 months Past 12 months 3 Nigeria has gone 13 months without Wild Polio Virus and 11 months without cVDPV2 13 months without WPV 11 months – cVDPV2 4 Challenges and Mitigation strategies 5 SIAs 6 Before the onset of the Wild Polio Virus Outbreak in July 2016, there were several unreached settlements in Borno Borno Accessibility Status by Ward, March 2016 # of Wards in % Partially LGAs % Fully Accessible % Inaccessible LGA Accessible Abadam 10 0% 0% 100% Askira-Uba 13 100% 0% 0% Bama 14 14% 0% 86% Bayo 10 100% 0% 0% Biu 11 91% 9% 0% Chibok 11 100% 0% 0% Damboa 10 20% 0% 80% Dikwa 10 10% 0% 90% Gubio 10 50% 10% 40% Guzamala 10 0% 0% 100% Gwoza 13 8% 8% 85% Hawul 12 83% 17% 0% Jere 12 50% 50% 0% Kaga 15 0% 7% 93% Kala-Balge 10 0% 0% 100% Konduga 11 0% 64% 36% Kukawa 10 20% 0% 80% Kwaya Kusar 10 100% 0% 0% Mafa 12 8% 0% 92% Magumeri 13 100% 0% 0% Maiduguri 15 100% 0% 0% Marte 13 0% 0% 100% Mobbar 10 0% 0% 100% Monguno 12 8% 0% 92% Ngala 11 0% 0% 100% Nganzai 12 17% 0% 83% Shani 11 100% 0% 0% State 311 41% 6% 53% 7 Source: Borno EOC Data team analysis Four Strategies were deployed to expand polio vaccination reach and increase population immunity in Borno state SIAs RES2 RIC4 Special interventions 12