CHAPTER 9 LAND TENURE Introduction 9.1 the Most

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOLONEC Shared Lives on Nigena Country

Shared lives on Nigena country: A joint Biography of Katie and Frank Rodriguez, 1944-1994. Jacinta Solonec 20131828 M.A. Edith Cowan University, 2003., B.A. Edith Cowan University, 1994 This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities (Discipline – History) 2015 Abstract On the 8th of December 1946 Katie Fraser and Frank Rodriguez married in the Holy Rosary Catholic Church in Derby, Western Australia. They spent the next forty-eight years together, living in the West Kimberley and making a home for themselves on Nigena country. These are Katie’s ancestral homelands, far from Frank’s birthplace in Galicia, Spain. This thesis offers an investigation into the social history of a West Kimberley couple and their family, a couple the likes of whom are rarely represented in the history books, who arguably typify the historic multiculturalism of the Kimberley community. Katie and Frank were seemingly ordinary people, who like many others at the time were socially and politically marginalised due to Katie being Aboriginal and Frank being a migrant from a non-English speaking background. Moreover in many respects their shared life experiences encapsulate the history of the Kimberley, and the experiences of many of its people who have been marginalised from history. Their lives were shaped by their shared faith and Katie’s family connections to the Catholic mission at Beagle Bay, the different governmental policies which sought to assimilate them into an Australian way of life, as well as their experiences working in the pastoral industry. -

(G-FLOWS) Task 6: Groundwater Recharge

Facilitating Long Term Out‐Back Water Solutions (G‐FLOWS) Task 6: Groundwater recharge characteristics across key priority areas Leaney, FW, Taylor, AR, Jolly, ID and Davies PJ Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series No. 13/6 www.goyderinstitute.org Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series ISSN: 1839‐2725 The Goyder Institute for Water Research is a partnership between the South Australian Government through the Department for Environment, Water and Natural Resources, CSIRO, Flinders University, the University of Adelaide and the University of South Australia. The Institute will enhance the South Australian Government’s capacity to develop and deliver science‐based policy solutions in water management. It brings together the best scientists and researchers across Australia to provide expert and independent scientific advice to inform good government water policy and identify future threats and opportunities to water security. Enquires should be addressed to: Goyder Institute for Water Research Level 1, Torrens Building 220 Victoria Square, Adelaide, SA, 5000 tel: 08‐8303 8952 e‐mail: [email protected] Citation Leaney, FW, Taylor, AR, Jolly, ID, and Davies PJ, 2013, Facilitating Long Term Out‐Back Water Solutions (G‐FLOWS) Task 6: Groundwater recharge characteristics across key priority areas, Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series No. 13/6, Adelaide, South Australia Copyright © 2013 CSIRO To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of CSIRO. Disclaimer The Participants advise that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research and does not warrant or represent the completeness of any information or material in this publication. -

27 October, 1965

(Wednesday, 27 October, 1965.] 1831 as submitted to us Is evading the Issue, and It Is not an acceptance by the Government I14rgitatn AeseuxhIly of a responsibility in this matter. All residents of the Gascoyne area-the Wednesday, the 27th October, 1965 commercial banana and vegetable growers, and all the citizens In Carnarvon-know CONTENTS what a cessation of the flow of the Gas- Page coyne River means to them because of the ANNUAL ESTIMATES, 19654-- salt content In the domestic water used Committee of Supply : Generai DtbatO- by every man, woman and child in the Speakers on Financial Policy- reticulated areas. Because of that salt Mr. Grayden ........ ....1853 content the quality of the water depre- Mr. Guthrie 1848 ciates rapidly. Therefore, this is not Mr. Hall.. ....... .. ta18g merely a matter of concern to industry on Mr. Ithatin ....... Ist. the Gascoyne; It is a serious matter for Mr. Itowberry ........ ISO. the whole population of the Gascoyne. Mr. Toms 1856 Mr. Williams ...IN The increased population brought about by the advent of the tracking station is BILLS- such that it is hard to find a building Audit Act Amendment fli--Council's block except in the subdivisions proposed Amendments 1840 at the foot of Brown's Range, and they are Betting investment Tax Act Amendment miles from the centre of the town. There Bill- is no other room for Carnarvon to grow Intro. Irf. 1832 because of its situation. There is not an Constitution Acts Amendment Bill (No. acre left. 2)-Retred 1877 The Hon. H. C. Strickland: Only be- Dental Hygienists Registration Bill-2r. -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

Djambawa Marawili

DJAMBAWA MARAWILI Date de naissance : 1953 Communauté artistique : Yirrkala Langue : Madarrpa Support : pigments naturels sur écorce, sculpture sur bois, gravure sur linoleum Nom de peau : Yirritja Thèmes : Yinapungapu, Yathikpa, Burrut'tji, Baru - crocodile, heron, fish, eagle, dugong Djambawa Marawili (born 1953) is an artist who has experienced mainstream success (as the winner of the 1996 Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art award Best Bark Painting Prize and as an artist represented in most major Australian institutional collections and several important overseas public and private collections) but for whom the production of art is a small part of a much bigger picture. Djambawa as a senior artist as well as sculpture and bark painting has produced linocut images and produced the first screenprint image for the Buku-Larr\gay Mulka Printspace. His principal roles are as a leader of the Madarrpa clan, a caretaker for the spiritual wellbeing of his own and other related clan’s and an activist and administrator in the interface between non-Aboriginal people and the Yol\u (Aboriginal) people of North East Arnhem Land. He is first and foremost a leader, and his art is one of the tools he uses to lead. As a participant in the production of the Barunga Statement (1988),which led to Bob Hawke’s promise of a treaty, the Royal Commission into Black Deaths in Custody and the formation of ATSIC , Djambawa drew on the sacred foundation of his people to represent the power of Yolngu and educate ‘outsiders’ in the justice of his people’s struggle for recognition. -

ENVIRONMENTAL SCOPING DOCUMENT Pilbara Iron Ore & Infrastructure Project

ENVIRONMENTAL SCOPING DOCUMENT Pilbara Iron Ore & Infrastructure Project: East-West Railway and Mine Sites (Stage B) (Assessment No. 1520) for Fortescue Metals Group Limited ENVIRON AUSTRALIA PTY LTD FORTESCUE METALS GROUP LIMITED Suite 7, The Russell Centre 159 Adelaide Terrace Fortescue House East Perth WA 6004 50 Kings Park Road, West Perth Tel.: +618 9225 5199 Western Australia 6005 Fax: +618 9225 5155 Tel.: +618 9266 0111 A.C.N. 095 437 442 Fax: +618 9266 0188 A.C.N. 57 002 594 872 Ref: Stage B Scoping final 16 Nov 04 16 November 2004 Environmental Scoping Document Pilbara Iron Ore & Infrastructure Project: East-West railway and Mine Sites (Stage B) 16 November 2004 for Fortescue Metals Group Limited Page i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. 1. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................1 1.1 THE PROPOSAL ....................................................................................................... 1 1.2 NEED FOR THE PROJECT..................................................................................... 3 1.3 PROJECT BENEFITS ............................................................................................... 3 1.4 PROPONENT ............................................................................................................. 4 2. PROJECT DESCRIPTION .................................................................................................... 5 2.1 PROJECT LOCATION ............................................................................................ -

East Kimberley Impact Assessment Project

East Kimberley Impact Assessment Project HISTORICAL NOTES RELEVANT TO IMPACT STORIES OF THE EAST KIMBERLEY Cathie Clement* East Kimberley Working Paper No. 29 ISBN O 86740 357 8 ISSN 0816...,6323 A Joint Project Of The: Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies Australian National University Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies Anthropology Department University of Western Australia Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia The aims of the project are as follows: 1. To compile a comprehensive profile of the contemporary social environment of the East Kimberley region utilising both existing information sources and limited fieldwork. 2. Develop and utilise appropriate methodological approaches to social impact assessment within a multi-disciplinary framework. 3. Assess the social impact of major public and private developments of the East Kimberley region's resources (physical, mineral and environmental) on resident Aboriginal communities. Attempt to identify problems/issues which, while possibly dormant at present, are likely to have implications that will affect communities at some stage in the future. 4. Establish a framework to allow the dissemination of research results to Aboriginal communities so as to enable them to develop their own strategies for dealing with social impact issues. 5. To identify in consultation with Governments and regional interests issues and problems which may be susceptible to further research. Views expressed in the Projecfs publications are the views of the authors, and are not necessarily shared by the sponsoring organisations. Address correspondence to: The Executive Officer East Kimberley Project CRES, ANU GPO Box4 Canberra City, ACT 2601 HISTORICAL NOTES RELEVANT TO IMPACT STORIES OF THE EAST KIMBERLEY Cathie Clement* East Kimberley Working Paper No. -

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (The Department) to the Questions on Notice That Arose Duringthe 6 February Public Hearing of the Committee

~ubmission N~. C~ ~ Australian Government I-v. Department ofAgriculture, Fisheries and Fores~ Date Received.. ~ o ~ ~Th7~) Ms Cheryl Scarlett Inquiry Secretary House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres StraitIslander Affairs Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Ms Scariett I thank the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Tones Strait Islander Affairs (the Committee) for the opportunity to contribute to its inquiry into Indigenous employment. As requested, here are the responses from the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (the Department) to the questions on notice that arose duringthe 6 February Public Hearing of the Committee. Question I — Report on Indleenous Employment in RuralIndustries The initial question on notice asked by the Committee was regarding a report by the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics (ABARE) on Indigenous employment in rural industries. I am now in a position to confirm that ABARE is expecting to publish this report by 31 March2006 on its website (w~vw abare. ~ov.au) Question 2 — FarmBis Statistics The second piece of information requested by the Committee was a State and Territory breakdown of Indigenous people’s participation in FarmBis programs. This information has been collated and is included at Enclosure 1 Question 3 — Tiwi IslandsForestry The Committee requested more specific information relating to the involvement of the Tiwi Island Community in Department’s National Indigenous Forestry Strategy. The Tiwi Forestry Project is a partnership between Great Southern Plantations Limitedand the Tiwi Land Council. The Tiwi Land Council was established in 1978, under the AboriginalLand Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth), and represents the Tiwi people who hold inalienable freehold title to their land under the Act. -

Children of the Intervention

CHILDREN OF THE INTERVENTION Aboriginal Children Living in the Northern Territory of Australia A Submission to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child June 2011 ‘concerned Australians’ June 2011 CHILDREN OF THE INTERVENTION Aboriginal Children Living in the Northern Territory of Australia A Submission to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child Prepared by: Michel e Harris OAM Georgina Gartland June 2011 1 ‘concerned Australians’ June 2011 2 ‘concerned Australians’ June 2011 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5‐6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6‐7 BASIC HEALTH AND WELFARE Overcrowding, Poor Health and Housing 8‐11 Child Nutrition 11‐13 Other Pressures on Family Life 14‐15 SPECIAL PROTECTION MEASURES Affirming Culture 16‐17 EDUCATION, LEISURE AND CULTURAL ACTIVITIES Education 18‐20 CONCLUSION 20 Appendices I Statement by Aboriginal Elders of the Northern Territory ‘To The People of Australia’ 21 ii Homeland Learning Centres (HLC) 22‐23 iii Comparison Between Two Schools 24 iv Build A Future For Our Children – Gawa School 25‐27 3 ‘concerned Australians’ June 2011 4 ‘concerned Australians’ June 2011 Introduction Aboriginal children living in the prescribed areas of the Northern Territory live under legislation that does not affect Aboriginal children in any other parts of Australia, or any other children who live in Australia whatever their ethnic grouping. It is for this reason that we are providing a complementary report to the Australian NGO Report Listen to Children in order to draw specific attention to the situation of children living in the Northern Territory. This legislation, known as Social Security and Other Legislation Amendment (Welfare Reform and Reinstatement of the Racial Discrimination Act) 2009, with small changes, has dominated the lives of all Northern Territory Aboriginal people since 21 June 2007. -

Australian Radiation Laboratory R

AR.L-t*--*«. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. HOUSING & COMMUNITY SERVICES Public Health Impact of Fallout from British Nuclear Weapons Tests in Australia, 1952-1957 by Keith N. Wise and John R. Moroney Australian Radiation Laboratory r. t J: i AUSTRALIAN RADIATION LABORATORY i - PUBLIC HEALTH IMPACT OF FALLOUT FROM BRITISH NUCLEAR WEAPONS TESTS IN AUSTRALIA, 1952-1957 by Keith N Wise and John R Moroney ARL/TR105 • LOWER PLENTY ROAD •1400 YALLAMBIE VIC 3085 MAY 1992 TELEPHONE: 433 2211 FAX (03) 432 1835 % FOREWORD This work was presented to the Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia in 1985, but it was not otherwise reported. The impetus for now making it available to a wider audience came from the recent experience of one of us (KNW)* in surveying current research into modelling the transport of radionuclides in the environment; from this it became evident that the methods we used in 1985 remain the best available for such a problem. The present report is identical to the submission we made to the Royal Commission in 1985. Developments in the meantime do not call for change to the derivation of the radiation doses to the population from the nuclear tests, which is the substance of the report. However the recent upward revision of the risk coefficient for cancer mortality to 0.05 Sv"1 does require a change to the assessment we made of the doses in terms of detriment tc health. In 1985 we used a risk coefficient of 0.01, so that the estimates of cancer mortality given at pages iv & 60, and in Table 7.1, need to be multiplied by five. -

Managing Indigenous Pastoral Lands

module three land information MANAGING INDIGENOUS PASTORAL LANDS Pub no. 14/019 McClelland Rural Services Pty Ltd MODULE 3 land information Contents Introduction 3 List of Tables Indigenous Land Rights and Pastoral Figure 3.1 Map of Northern Territory Land Holdings 5 Aboriginal Land 7 Land Rights 5 Figure 3.2 Map of Queensland Indigenous Pastoral Land Holdings 5 Aboriginal Land 8 Land Tenure 10 Figure 3.3 Map of Western Australian Indigenous Lands - Aboriginal Land (Kimberley & Pilbara) 9 Definitions and Complexities 10 Indigenous Land Holding Arrangements List of Photos in the Northern Territory 11 Cover Photo – Ghost gums Legal Framework 11 Permitted Land Uses 11 Indigenous Land Holding Arrangements in Queensland 12 Legal Framework 12 Forms of Land Acquisition 12 Renewals of Pastoral Leases 13 Indigenous Land Holding Arrangements in Western Australia 14 Legal Framework 14 Forms of Land Acquisition 14 Pastoral Lease Reform 15 Renewals of Pastoral Leases 15 Role of Land Councils 18 Overview 18 Northern Territory 18 Queensland 18 Western Australia 19 Land Use Agreements 20 Mining Tenures and Income from Mining on Indigenous Land 22 Mining Tenures 22 Mining Income 24 2 MODULE 3 land information Introduction Module 3 describes the rights and obligations of Indigenous land holders in the northern Australia pastoral industry. Indigenous land tenure is administered differently in the Northern Territory (NT), Queensland (Qld) and Western Australia (WA) which has resulted in a high degree of complexity. In addition, this whole area is undergoing a great deal of change. • In November 2012, the Northern Australia Ministerial Forum (NAMF) initiated a review of land tenure management across northern Australia. -

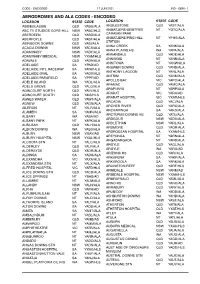

Aerodromes and Ala Codes

CODE - ENCODED 17 JUN 2021 IND - GEN - 1 AERODROMES AND ALA CODES - ENCODED LOCATION STATE CODE LOCATION STATE CODE ABBIEGLASSIE QLD YABG/ALA ANGLESTONE QLD YAST/ALA ABC TV STUDIOS GORE HILL NSW YABC/HLS ANMATJERE/GEMTREE NT YGTC/ALA ABERDEEN QLD YABD/ALA CARAVAN PARK ABERFOYLE QLD YABF/ALA ANMATJERE/PINE HILL NT YPHS/ALA STATION ABINGDON DOWNS QLD YABI/ALA ANNA CREEK SA YANK/ALA ACACIA DOWNS NSW YACS/ALA ANNA PLAINS HS WA YAPA/ALA ADAMINABY NSW YADY/ALA ANNANDALE QLD YADE/ALA ADAMINABY MEDICAL NSW YXAM/HLS ANNINGIE NT YANN/ALA ADAVALE QLD YADA/ALA ANNITOWA NT YANW/ALA ADELAIDE SA YPAD/AD ANSWER DOWNS QLD YAND/ALA ADELAIDE INTL RACEWAY SA YAIW/HLS ANTHONY LAGOON NT YANL/ALA ADELAIDE OVAL SA YAOV/HLS ANTRIM QLD YANM/ALA ADELAIDE/PARAFIELD SA YPPF/AD APOLLO BAY VIC YAPO/ALA ADELE ISLAND WA YADL/ALA ARAMAC QLD YAMC/ALA ADELS GROVE QLD YALG/ALA ARAPUNYA NT YARP/ALA AGINCOURT NORTH QLD YAIN/HLS ARARAT VIC YARA/AD AGINCOURT SOUTH QLD YAIS/HLS ARARAT HOSPITAL VIC YXAR/HLS AGNES WATER QLD YAWT/ALA ARCADIA QLD YACI/ALA AGNEW QLD YAGN/ALA ARCHER RIVER QLD YARC/ALA AILERON NT YALR/ALA ARCKARINGA SA YAKG/ALA ALAMEIN SA YAMN/ALA ARCTURUS DOWNS HS QLD YATU/ALA ALBANY WA YABA/AD ARDGOUR NSW YADU/ALA ALBANY PARK NT YAPK/ALA ARDLETHAN NSW YARL/ALA ALBILBAH QLD YALH/ALA ARDMORE QLD YAOR/ALA ALBION DOWNS WA YABS/ALA ARDROSSAN HOSPITAL SA YXAN/HLS ALBURY NSW YMAY/AD AREYONGA NT YARN/ALA ALBURY HOSPITAL NSW YXAL/HLS ARGADARGADA NT YARD/ALA ALCOOTA STN NT YALC/ALA ARGYLE QLD YAGL/ALA ALDERLEY QLD YALY/ALA ARGYLE WA YARG/AD ALDERSYDE QLD YADR/ALA ARIZONA HS