Europe's Asylum and Migration Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Dictatorship to Democracy: Iraq Under Erasure Abeer Shaheen

From Dictatorship to Democracy: Iraq under Erasure Abeer Shaheen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 ©2015 Abeer Shaheen All rights reserved ABSTRACT From Dictatorship to Democracy: Iraq under Erasure Abeer Shaheen This dissertation examines the American project in Iraq between 1991 and 2006. It studies the project’s conceptual arc, shifting ontology, discourses, institutions, practices, and technologies in their interrelatedness to constitute a new Iraq. It is an ethnography of a thixotropic regime of law and order in translation; a circuit through various landscapes and temporalities to narrate the 1991 war, the institutionalization of sanctions and inspection regimes, material transformations within the American military, the 2003 war and finally the nation- building processes as a continuous and unitary project. The dissertation makes three central arguments: First, the 2003 war on Iraq was imagined through intricate and fluid spaces and temporalities. Transforming Iraq into a democratic regime has served as a catalyst for transforming the American military organization and the international legal system. Second, this project has reordered the spatialized time of Iraq by the imposition of models in translation, reconfigured and reimagined through a realm of violence. These models have created in Iraq a regime of differential mobility, which was enabled through an ensemble of experts, new institutions and calculative technologies. Third, this ensemble took Iraq as its object of knowledge and change rendering Iraq and Iraqis into a set of abstractions within the three spaces under examination: the space of American military institutions; the space of international legality within the United Nations; and, lastly, the material space of Baghdad. -

December 2015

20 Mr Cameron, 25 Formal complaints 35 In Prison there ought to be more the prisoners’ prerogative Permanently the National Newspaper for Prisoners & Detainees old lags in Whitehall How to make a formal The politics of the IPP Plans to revolutionise complaint the right way sentence by Geir Madland a voice for prisoners 1990 - 2015 jails so prisoners leave by Paul Sullivan A ‘not for profit’ publication / ISSN 1743-7342 / Issue No. 198 / December 2015 / www.insidetime.org rehabilitated and ready for Seasons greetings to all our readers An average of 60,000 copies distributed monthly Independently verified by the Audit Bureau of Circulations work by Jonathan Aitken POA Gives NOMS 28 DAYS to put its House in Order Eric McGraw TEN MOST OVERCROWDED PRISONS at the end of October 2015 n a letter to Michael Spurr, Chief Prison Designed Actually Executive of the National Offender Man- to hold holds agement Service (NOMS), the Prison Officers’ Association (POA) has issued a Kennet 175 317 28-day notice requiring NOMS ‘to Leeds 669 1,166 Iaddress a number of unlawful and widespread Wandsworth 943 1,577 practices which exacerbate the parlous health and safety situation’ in prisons in England and Swansea 271 442 Wales. Failure to do so, they warn, will lead to Exeter 318 511 ‘appropriate legal action’. Durham 595 928 Leicester 214 331 The letter, dated November 11, 2015, states Preston 455 695 that the prison service does not have enough staff to operate safely. This, says the POA, has Brixton 528 802 been caused by a ‘disastrously miscalculated’ Lincoln 403 611 redundancy plan devised by the Government which has reduced the number of staff on the ‘mistaken assumption’ that prison numbers would fall: in fact, as everyone knows, they their ‘Certified Normal Accommodation’ by have risen. -

Governors' Briefing Paper Elements

BBC Trust Review of Breadth of Opinion: follow up December 2014 1 Contents Background 3 Trust Commentary 4 EXECUTIVE UPDATE ON BREADTH OF OPINION IMPARTIALITY REVIEW 6 Overview 6 Use of ‘stand-back’ moments and of story champions 6 Role of the Multimedia Editor in co-ordinating coverage 8 Dissemination of opinion gathered by the audience response team 9 Cross-promotion of BBC services 10 Pan-BBC forum on religion and ethics 11 Training and increasing knowledge about religion and ethics 12 Challenging assumptions on the shared consensus on any story 13 2 Background The BBC is unique among UK broadcasters in its commitment to impartiality across its output. This commitment is at the heart of the BBC’s relationship with its audiences. In 2012 the BBC Trust commissioned the former Chief Executive of ITV, Stuart Prebble, to write an independent report on Breadth of Opinion in BBC output, including audience research and content analysis. The review focused on three key areas; the UK’s relationship with the EU, immigration, and religion and ethics. One of the challenges was to undertake rigorous analysis on something as nebulous as opinions. This impartiality review on Breadth of Opinion1 was published in July 2013 and the Trust welcomed the report’s findings that the range of opinion on BBC output is remarkable and impressive. However, the author advised that it demands “continuous vigilance in ensuring that views which may not be palatable to journalists are given an appropriate airing, and a constant challenging of assumptions underlying the approach taken to stories”. In response, the BBC outlined plans which included: establishing a pan-BBC forum on religion and ethics, appointing story champions for important and long-running stories, and expanding its use of cross-trailing between programmes and BBC online. -

Arab Spring” June 2012

A BBC Trust report on the impartiality and accuracy of the BBC’s coverage of the events known as the “Arab Spring” June 2012 Getting the best out of the BBC for licence fee payers A BBC Trust report on the impartiality and accuracy of the BBC‟s coverage of the events known as the “Arab Spring” Contents BBC Trust conclusions 1 Summary 1 Context 2 Summary of the findings by Edward Mortimer 3 Summary of the research findings 4 Summary of the BBC Executive‟s response to Edward Mortimer‟s report 5 BBC Trust conclusions 6 Independent assessment for the BBC Trust by Edward Mortimer - May 2012 8 Executive summary 8 Introduction 11 1. Framing of the conflict/conflicts 16 2. Egypt 19 3. Libya 24 4. Bahrain 32 5. Syria 41 6. Elsewhere, perhaps? 50 7. Matters arising 65 Summary of Findings 80 BBC Executive response to Edward Mortimer’s report 84 The nature of the review 84 Strategy 85 Coverage issues 87 Correction A correction was made on 25 July 2012 to clarify that Natalia Antelava reported undercover in Yemen, as opposed to Lina Sinjab (who did report from Yemen, but did not do so undercover). June 2012 A BBC Trust report on the impartiality and accuracy of the BBC‟s coverage of the events known as the “Arab Spring” BBC Trust conclusions Summary The Trust decided in June 2011 to launch a review into the impartiality of the BBC‟s coverage of the events known as the “Arab Spring”. In choosing to focus on the events known as the “Arab Spring” the Trust had no reason to believe that the BBC was performing below expectations. -

October 2015 2 Mailbag and Prison) to ‘Mailbag’, Inside Time, Botley Mills, Botley, Southampton, Hampshire SO30 2GB

the National Newspaper for Prisoners & Detainees THE 2015 KOESTLER AWARDS a voice for prisoners 1990 - 2015 RE:FORM is the UK’s annual national showcase of arts A ‘not for profit’ publication / ISSN 1743-7342 / Issue No. 196 / October 2015 / www.insidetime.org by prisoners, offenders on community sentences, secure An average of 60,000 copies distributed monthly Independently verified by the Audit Bureau of Circulations psychiatric patients and immigration detainees. SHRINK PRISON NUMBERS AND SAVE BILLIONS OF POUNDS Eric McGraw people are sentenced to serve them each year. They destroy lives and are too short to begin he number of men, women and chil- to tackle the causes of offending. Ministry of dren in prison’s in England and Wales Justice research has concluded that suspend- has almost doubled in 25 years - from ed or community sentences are cheaper and result in less offending. fewer than 45,000 in 1990 to more than 85,000 today. Reducing the l Limit the use of remand. prisonT population to its level when Margaret More than 8,000 people in prison have not Thatcher was Prime Minister would allow been found guilty of an offence. While re- governors to improve prison conditions, mand is needed, it’s used far too often. Sev- which were described in July by the Chief In- enty percent of people remanded in custody spector of Prison’s as their worst in a decade. do not go on to receive a custodial sentence. In a submission to the Government’s Spend- l Reduce recalls to custody and use women’s ing Review 2015 the Howard League for Pe- centres in the community, not prisons. -

Vr for News: the New Reality? Zillah Watson

VR FOR NEWS: THE NEW REALITY? ZILLAH WATSON 2017 DIGITAL NEWS PROJECT DIGITAL NEWS PROJECT DIGITAL NEWS PROJECT DIGITAL NEWS DIGITAL PROJECT NEWS DIGITAL PROJECT NEWS DIGITAL PROJECT NEWS DIGITAL CONTENTS About the Author 5 Acknowledgements 5 Executive Summary 6 Introduction 7 1. VR and News: What’s the Attraction? 10 2. The Content Challenge 14 3. What Does the VR Newsroom Look Like in May 2017? 26 4. Delivering VR to Consumers 28 5. A News VR Proposition to Win Tomorrow’s Audience 33 Conclusion 38 References 41 List of Interviewees 42 VR FOR NEWS: THE NEW REALITY? About the Author Zillah Watson has led the editorial development of virtual reality experimentation at the BBC, with a focus on news. A former current affairs producer and head of editorial standards for BBC Radio 4, she has worked in BBC Research and Development for the last four years to understand the future of content, data, and online curation. She was executive producer of ground-breaking 360 VR films including Inside the Large Hadron Collider 360, The Resistance of Honey, and Fire Rescue 360, all of which have been featured at international film festivals. She produced the first 360 BBC report from the Calais migrant camp in June 2015, and the first newsgathering 360 report with Matthew Price in the immediate aftermath of the Paris terror attacks in November 2015. She was executive producer of the award-winning interactive CGI VR productions The Turning Forest and We Wait. Acknowledgements I would like to thank not only the interviewees listed, but the many other people working in VR – from independent production companies through to university professors in journalism and computer science – who were so generous with their time in providing background information and context while I was researching this report. -

1 Refereed Paper Delivered at Australian

Mediated Hegemony: Interference in the post-Saddam Iraqi media sector Author Isakhan, Benjamin Published 2008 Conference Title Australasian Political Science Association (APSA)Conference Version Version of Record (VoR) Copyright Statement © The Author(s) 2008. The attached file is reproduced here in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. For information about this conference please refer to the conference’s website or contact the author. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/23016 Link to published version http://www.auspsa.org.au/ Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Refereed paper delivered at Australian Political Studies Association Conference 6 – 9 July 2008 Hilton Hotel, Brisbane, Australia Mediated Hegemony: Interference in the post-Saddam Iraqi media sector Mr Benjamin Isakhan, Doctoral Candidate Griffith University, Queensland Abstract: The toppling of Saddam in 2003 brought with it the re-emergence of the free press in Iraq. This has seen Iraq shift from only a handful of state media outlets that served as propaganda machines, to a vast array of Iraqi-owned newspapers, radio stations and television channels which are being fervently produced and avidly consumed across the nation. As is to be expected, there are several problems that have accompanied such a divergent, ad-hoc and highly volatile media landscape. Leaving aside important issues such as the dangers faced by Iraqi journalists and the lack of appropriate press laws, this paper focuses instead on the influence of both foreign and domestic political bodies on the post-Saddam Iraqi media sector. Among the foreign influences are Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United States, all of which fund, control and manipulate various Iraqi media outlets. -

Hulu: Under the Hood WE FIND GUESTS for YOUR SHOW

March 2018 Hulu: Under the hood WE FIND GUESTS FOR YOUR SHOW We are television bookers ready to find guests for your show. Guestbooker.com has media trained experts based across the US and the UK in a range of sectors, including; poliics, healthcare, security, law, business, finance and entertainment. Our team is based in London, New York City, Los Angeles, Washington D.C, Nashville, Dallas, Ausin, Miami and Chicago. Journal of The Royal Television Society March 2018 l Volume 55/3 From the CEO It has been an exciting That so many female journalists of Television, don’t miss Mark Lawson’s and illuminating end different ages and backgrounds were insightful profile of the great Macken- to the RTS’s winter among the night’s winners says a lot zie Crook. Meanwhile, our cover looks programme. Despite about the changing times that we are at the rise and rise of Hulu. I, for one, the “Beast from the living in. can’t wait to watch the second season East” bringing snow So, too, did our sold-out early- of The Handmaid’s Tale, coming soon on and ice to even Lon- evening event “Sale or scale”, when Channel 4. don’s Hyde Park Corner, this year’s a high-powered panel analysed the I look forward to seeing many of RTS Television Journalism Awards rapidly consolidating entertainment you at the RTS Programme Awards. generated a lot of genuine warmth. sector. Many thanks to the wonderful This is undoubtedly the most glamor- I’d like to thank everyone who panellists: Kate Bulkley, Mike Darcey, ous night in the RTS calendar. -

Table of Membership Figures For

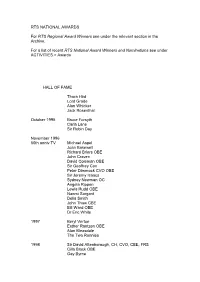

RTS NATIONAL AWARDS For RTS Regional Award Winners see under the relevant section in the Archive. For a list of recent RTS National Award Winners and Nominations see under ACTIVITIES > Awards HALL OF FAME Thora Hird Lord Grade Alan Whicker Jack Rosenthal October 1995 Bruce Forsyth Carla Lane Sir Robin Day November 1996 60th anniv TV Michael Aspel Joan Bakewell Richard Briers OBE John Craven David Coleman OBE Sir Geoffrey Cox Peter Dimmock CVO OBE Sir Jeremy Isaacs Sydney Newman OC Angela Rippon Lewis Rudd OBE Naomi Sargant Delia Smith John Thaw CBE Bill Ward OBE Dr Eric White 1997 Beryl Vertue Esther Rantzen OBE Alan Bleasdale The Two Ronnies 1998 Sir David Attenborough, CH, CVO, CBE, FRS Cilla Black OBE Gay Byrne David Croft OBE Brian Farrell Gloria Hunniford Gerry Kelly Verity Lambert James Morris 1999 Sir Alistair Burnet Yvonne Littlewood MBE Denis Norden CBE June Whitfield CBE 2000 Harry Carpenter OBE William G Stewart Brian Tesler CBE Andrea Wonfor In the Regions 1998 Ireland Gay Byrne Brian Farrell Gloria Hunniford Gerry Kelly James Morris 1999 Wales Vincent Kane OBE Caryl Parry Jones Nicola Heywood Thomas Rolf Harris AM OBE Sir Harry Secombe CBE Howard Stringer 2 THE SOCIETY'S PREMIUM AWARDS The Cossor Premium 1946 Dr W. Sommer 'The Human Eye and the Electric Cell' 1948 W.I. Flach and N.H. Bentley 'A TV Receiver for the Home Constructor' 1949 P. Bax 'Scenery Design in Television' 1950 Emlyn Jones 'The Mullard BC.2. Receiver' 1951 W. Lloyd 1954 H.A. Fairhurst The Electronic Engineering Premium 1946 S.Rodda 'Space Charge and Electron Deflections in Beam Tetrode Theory' 1948 Dr D. -

Confessional Journalism and Podcasting Kate Williams, University of Northampton

Page 66 Journalism Education Volume 9 number 1 Confessional journalism and podcasting Kate Williams, University of Northampton Abstract Broadcast reporters are trained to report on a story and not express opinions. Staying impartial is fundamental to their role and forms part of the UK broadcasting regula- tor Ofcom’s code, but what happens when the reporter is the story? In 2017, I was diagnosed with an extremely rare form of abdominal cancer. Medical literature quotes just 153 recorded cases of cystic peritoneal mesothelio- ma in the world. Apart from a few tentative tweets to see if I could find any other people with the same cancer, I didn’t tell my story. This is in complete contrast to my fellow news presenter on BBC Radio 5live, Rachael Bland - when diagnosed with breast cancer, she told her story. She blogged, tweeted and posted on Instagram as well as presenting an award-winning podcast. She wanted to report on her cancer to help as many people as possible know the facts. Sadly, Rachael died in September 2018. In the many tributes following her death, many said she had changed the conversation around cancer, normalis- ing the talk about the disease. With the rise of the podcast, there is a new type of con- fessional journalism. Broadcasters are expressing their opinions and telling previously untold stories in a new Comment & criticism Volume 9 number 1 Journalism Education page 67 way. Newspaper columnists have done this for years but for impartial broadcasters, trained not to express opin- ions when reporting on a story, a fundamental change is taking place as they start to tell their own stories adapt- ing to a new storytelling genre. -

Historical Precedent. American Press Policy in Occupied Iraq.Pdf

Historical Precedent? American Press Policy in Occupied Iraq Cora Sol Goldstein Department of Political Science California State University at Long Beach Long Beach, California 90840-4605 [email protected] Prepared for delivery at the 2007 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, August 30th-September 2nd, 2007. The American occupation of Germany (1945-1949) stands as a model of a successful exercise in democratization by force. In fact, top figures in the Bush administration, including Condoleezza Rice and Donald Rumsfeld, have compared the American experiences in postwar Germany and in postwar Iraq. In this paper, I compare American information control policy in Germany (1945-1949) and Iraq (2003-2006).The comparative analysis indicates that the American information control policy was very different in the two cases. In Germany, the U.S. Army and the Office of Military Government U.S. in Germany (OMGUS) exerted rigorous control over the media to block Nazi propaganda and introduce the American political agenda of democratization. With the emergence of the Cold War, OMGUS and its Soviet counterpart, the Sowjetische Militaradministration in Deutschland (SMAD), used all the avenues of mass communications and cultural affairs–newspapers, journals, feature and documentary films, posters, and radio–to disseminate their strategic propaganda and to deliver the messages coming from Washington and Moscow. Therefore, from 1945 to 1949, the Americans were able to shape the content of information in the American zone and sector. In the case of Iraq, the Coalition forces failed to exert a similar degree of information control. As a result of this strategic error, the insurgency and civilian movements opposed to the American presence in Iraq have been able to control information and spread their anti-American messages. -

Who Is Responsible in the Age of Intelligent Machines?

Media, Tech & Society: Who is responsible in the age of intelligent machines? Conference + Fair Monday 7th October 2019 BBC Radio Theatre Broadcasting House London W1 1AA TheSessions 10:00 Opening Keynote. Grace Boswood, COO BBC Design + Engineering 10:25 Whose AI Is It Anyway? Tina and guests examine the value of responsibility versus the cost of irresponsibility. Dr Indra Joshi, Sana Khareghani & Sandra Wachter 11:40 The Media Show - Do machines make the right choices for young people? Andrea Catherwood and guests explore the impact on young people of growing up in this new algorithmically-influenced culture and ask who is responsible for This session will be shaping the waythey think. recorded for broadcast on Anne Longfield OBE, Hanna Adan, Neil BBC Radio 4. Lawrence & Dr Nejra Van-Zalk 12:45 BBC Click - Is this responsible tech? Spencer Kelly hosts live on-stage tech demos…what could possibly go wrong?! 14:00 BBC Philharmonic Orchestra - Can AI compose music? You decide… Composer Robert Laidlow and the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra throw AI and human creativity into a big melting pot. Can you tell which bits are written by AI and by a human? 14:45 Beyond Fake News - A Disinformation Dystopia? The floor is yours! This Question Time style debate hosted by Kamal Ahmed, BBC News Editorial Director, will answer questions posed by you about disinformation, ‘fake news’ and synthetic media. Nahema Marchal, Rachel Botsman, Simon Cross & Tom Walker 15:50 NewsRevue - Alexa make me laugh! Live comedy with a fast-moving mix of sketches and songs about our relationship with technology from the NewsRevue team.