Estimated in 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phyllis Bennis

Phyllis Bennis: Resolving Iraq and Syria through Diplomacy, Not War a videoconference forum Monday, May 18, 2015 6:30-8:30 PM This event is free and open to the public; donations will be accepted. Multnomah Friends Meeting House 4312 SE Stark On-street parking is limited; Meeting House is 4-5 blocks from bus lines #15 (Belmont @ 42nd), #20 (Burnside @ 44th) or #75 (Cesar Chavez/39th @ Stark). Or watch it live on ustream.tv/channel/occucakes (remove ads using Firefox and AdBlockPlus) Phyllis Bennis of the Institute for Policy Studies will conduct a video forum in Portland including a question and answer period Appearing via the internet from the east coast, the renowned analyst will focus on the US War on ISIS (/Islamic State), the debate over the Authorization for Use of Military Force, and the effects on the people of Iraq and Syria of the US-led war-- in which Iran is playing a key role. Bennis has been an advocate for diplomatic solutions in light of the ongoing state of war the US has been in at least since the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001. Bennis will also give brief updates on Israel/Palestine and what's going on in Yemen. Coordinated by: Peace and Justice Works Iraq Affinity Group, funded in part by the Jan Bone Memorial Fund for public forums. cosponsored by Occupy Portland Elder Caucus, Americans United for Palestinian Human Rights (AUPHR), Oregon Physicians for Social Responsibility, Jewish Voice for Peace-Portland, American Friends Service Committee, Veterans for Peace Chapter 72, Pacific Green Party, Women's International League for Peace and Freedom-Portland, and others. -

Afghan National Security Forces Getting Bigger, Stronger, Better Prepared -- Every Day!

afghan National security forces Getting bigger, stronger, better prepared -- every day! n NATO reaffirms Afghan commitment n ANSF, ISAF defeat IEDs together n PRT Meymaneh in action n ISAF Docs provide for long-term care In this month’s Mirror July 2007 4 NATO & HQ ISAF ANA soldiers in training. n NATO reaffirms commitment Cover Photo by Sgt. Ruud Mol n Conference concludes ANSF ready to 5 Commemorations react ........... turn to page 8. n Marking D-Day and more 6 RC-West n DCOM Stability visits Farah 11 ANA ops 7 Chaghcharan n ANP scores victory in Ghazni n Gen. Satta visits PRT n ANP repels attack on town 8 ANA ready n 12 RC-Capital Camp Zafar prepares troops n Sharing cultures 9 Security shura n MEDEVAC ex, celebrations n Women’s roundtable in Farah 13 RC-North 10 ANSF focus n Meymaneh donates blood n ANSF, ISAF train for IEDs n New CC for PRT Raising the cup Macedonian mid fielder Goran Boleski kisses the cup after his team won HQ ISAF’s football final. An elated team-mate and team captain Elvis Todorvski looks on. Photo by Sgt. Ruud Mol For more on the championship ..... turn to page 22. 2 ISAF MIRROR July 2007 Contents 14 RC-South n NAMSA improves life at KAF The ISAF Mirror is a HQ ISAF Public Information product. Articles, where possible, have been kept in their origi- 15 RAF aids nomads nal form. Opinions expressed are those of the writers and do not necessarily n Humanitarian help for Kuchis reflect official NATO, JFC HQ Brunssum or ISAF policy. -

Defense Logistical Support Contracts in Iraq and Afghanistan: Issues for Congress

Defense Logistical Support Contracts in Iraq and Afghanistan: Issues for Congress Valerie Bailey Grasso Specialist in Defense Acquisition September 20, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33834 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Defense Logistical Support Contracts in Iraq and Afghanistan: Issues for Congress Summary This report examines Department of Defense (DOD) logistical support contracts for troop support services in Iraq and Afghanistan administered through the U.S. Army’s Logistics Civil Augmentation Program (LOGCAP), as well as legislative initiatives which may impact the oversight and management of logistical support contracts. LOGCAP is an initiative designed to manage the use of civilian contractors that perform services during times of war and other military mobilization. The first LOGCAP was awarded in 1992. Four LOGCAP contracts have been awarded for combat support services in Iraq and Afghanistan. The current LOGCAP III contractor supports the drawdown in Iraq by providing logistical services, theater transportation, augmentation of maintenance services, and other combat support services. On April 18, 2008, DOD announced the Army’s LOGCAP IV contract awards to three companies—DynCorp International LLC, Fort Worth, TX; Fluor Intercontinental, Inc, Greenville, SC; and KBR, Houston, TX, through a full and open competition. The LOGCAP IV contract calls for each company to compete for task orders. Each company may be awarded up to $5 billion annually for troop support services with a maximum annual value of $15 billion. As of March 2010, each company has been awarded at least one task order under LOGCAP IV. Over the life of LOGCAP IV, the maximum contract value is $150 billion. -

U. S. Foreign Policy1 by Charles Hess

H UMAN R IGHTS & H UMAN W ELFARE U. S. Foreign Policy1 by Charles Hess They hate our freedoms--our freedom of religion, our freedom of speech, our freedom to vote and assemble and disagree with each other (George W. Bush, Address to a Joint Session of Congress and the American People, September 20, 2001). These values of freedom are right and true for every person, in every society—and the duty of protecting these values against their enemies is the common calling of freedom-loving people across the globe and across the ages (National Security Strategy, September 2002 http://www. whitehouse. gov/nsc/nss. html). The historical connection between U.S. foreign policy and human rights has been strong on occasion. The War on Terror has not diminished but rather intensified that relationship if public statements from President Bush and his administration are to be believed. Some argue that just as in the Cold War, the American way of life as a free and liberal people is at stake. They argue that the enemy now is not communism but the disgruntled few who would seek to impose fundamentalist values on societies the world over and destroy those who do not conform. Proposed approaches to neutralizing the problem of terrorism vary. While most would agree that protecting human rights in the face of terror is of elevated importance, concern for human rights holds a peculiar place in this debate. It is ostensibly what the U.S. is trying to protect, yet it is arguably one of the first ideals compromised in the fight. -

KBR 2020 Proxy Statement

TO OUR FOR MAKING ANYTHING POSSIBLE NOTICE OF ANNUAL MEETING OF STOCKHOLDERS AND PROXY STATEMENT Dear KBR, Inc. Stockholders, As I write this letter to you for our Proxy Statement, the world is in the middle of a global health crisis. The COVID-19 outbreak is an unprecedented event, and although this is a time of significant uncertainty, we are taking actions to support our people, their families and our customers. With operations in China and South Korea we had an early warning of the potential impact of the virus, and this allowed us to plan ahead and stress test our operations for remote working. I am humbled by the amazing efforts of our people around the globe who have pulled together, shared ideas and implemented best practices to continue to provide world-class service for our customers while also protecting their well-being and the health and safety of their colleagues. It is this can-do, people-centric and forward-thinking culture that makes KBR a great company to be part of. It is thus a great honor to share with you this special Proxy Statement, which marks the 100-year anniversary of our company, and to dedicate it to the people who made it possible — our incredible employees. It is remarkable to think of all they have accomplished throughout KBR’s history, beginning in the earliest days, when they worked with teams of wagons and mules to pave rural roads, to today, when they are helping NASA return to the moon and discover life beyond Earth. Over the past 100 years, KBR has grown into an innovative and dynamic global company, and I am proud to be a part of this journey. -

And Pale Odia Palestinian Woman in Jabaliya Camp, Gaza Strip

and Pale odia Palestinian woman in Jabaliya Camp, Gaza Strip. Her home was demolished by Israeli military, (p.16) (Photo: Neal Cassidy) nunTHE JOURNAL OF SUBSTANCE FOR PROGRESSIVE WOMEN VOL. XV SUMMER 1990 PUBLISHER/EDITOR IN CHIEF Merle Hoffman MANAGING EDITOR Beverly Lowy ASSOCIATE EDITOR Eleanor J. Bader ASSISTANT EDITOR Karen Aisenberg EDITOR AT LARGE Phyllis Chester CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Charlotte Bunch Vinie Burrows Naomi Feigelson Chase Irene Davall FEATURES Above: Goats on a porch at Toi Derricotte Mandala. All animals are treated with Roberta Kalechofsky BREAKING BARRIERS: affection and respect, even the skunks. Flo Kennedy WOMEN AND MINORITIES IN (p.10) (Photo: Helen M. Stummer) Fred Pelka THE SCIENCES Cover: A single mother and her Helen M. Stummer ON THE ISSUES interviews children find permanency in a H.O.M.E.- ART DIRECTORS Paul E. Gray, President of MIT, and built home. (Photo: Helen M. Stummer) Michael Dowdy Dean of Student Affairs, Shirley M. Julia Gran McBay, on sexism and racism in A SONG SO BRAVE — ADVERTISING AND SALES academia 7 PHOTO ESSAY DIRECTOR Text By Phyllis Chesler Carolyn Handel H.O.M.E. Photos By Joan Roth ONE WOMAN'S APPROACH Phyllis Chesler and an international ON THE ISSUES: A feminist, humanist TO SOCIETY'S PROBLEMS group of feminists present a Torah to publication dedicated to promoting By Helen M. Stummer political action through awareness and the women of Jerusalem 19 education; working toward a global Visual sociologist Helen M. Stummer political consciousness; fostering a spirit profiles a unique program to combat TO PEE OR NOT TO PEE of collective responsibility for positive homelessness, poverty and By Irene Davall social change; eradicating racism, disenfranchisement 10 A humorous recollection of the "pee- sexism, ageism, speciesism; and support- in" that forced Harvard to examine its ing the struggle of historically disenfran- FROM STONES TO sexism 20 chised groups to protect and defend STATEHOOD themselves. -

Medical Discrimination in the Time of COVID-19: Unequal Access to Medical Care in West Bank and Gaza Hana Cooper Seattle University ‘21, B.A

Medical Discrimination in the Time of COVID-19: Unequal Access to Medical Care in West Bank and Gaza Hana Cooper Seattle University ‘21, B.A. History w/ Departmental Honors ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE A SYSTEM OF DISCRIMINATION COVID-19 IMPACT Given that PalestiniansSTRACT are suffering from As is evident from headlines over the last year, Palestinians are faring much worse While many see the founding of Israel in 1948 as the beginning of discrimination against COVID-19 has amplified all of the existing issues of apartheid, which had put Palestinians the COVID-19 pandemic not only to a under the COVID-19 pandemic than Israelis. Many news sources focus mainly on the Palestinians, it actually extends back to early Zionist colonization in the 1920s. Today, in a place of being less able to fight a pandemic (or any major, global crisis) effectively. greater extent than Israelis, but explicitly present, discussing vaccine apartheid and the current conditions of West Bank, Gaza, discrimination against Palestinians continues at varying levels throughout West Bank, because of discriminatory systems put into and Palestinian communities inside Israel. However, few mainstream news sources Gaza, and Israel itself. Here I will provide some examples: Gaza Because of the electricity crisis and daily power outages in Gaza, medical place by Israel before the pandemic began, have examined how these conditions arose in the first place. My project shows how equipment, including respirators, cannot run effectively throughout the day, and the it is clear that Israel is responsible for taking the COVID-19 crisis in Palestine was exacerbated by existing structures of Pre-1948 When the infrastructure of what would eventually become Israel was first built, constant disruptions in power cause the machines to wear out much faster than they action to ameliorate the crisis. -

Press Release United Nations Department of Public Information • News and Media Services Division • New York PAL/1887 PI/1354 13 June 2001

Press Release United Nations Department of Public Information • News and Media Services Division • New York PAL/1887 PI/1354 13 June 2001 DPI TO HOST INTKRNATIONAI, MEDIA ENCOUNTER ON QUESTION OF PALESTINE IN PARIS, 18 - 19 JUNE Search for Peace in Middle East, Role of United Nations To Be Discussed Prominent journalists and Middle East experts, including senior officials and lawmakers from Israel and the Palestinian Authority, will meet at the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) headquarters in Paris, on 18 and 19 June, at an international media encounter on the question of Palestine organized by the Department of Public Information (DPI). The overall theme of the encounter is "The search for peace in the Middle East". It is designed as a forum where media representatives and international experts will have an opportunity to discuss the status of the peace process, ways and means to break the deadlock, and the cycle of violence and reporting about the developments in the Middle East. They will also discuss the role of the United Nations in the question of Palestine and in the overall search for peace in the Middle East. The Secretary-General of the United Nations is expected to issue a message welcoming the participants, which will be delivered by Shashi Tharoor, Interim Head, DPI. The Secretary-General of the French Foreign Ministry, Loic Hennekinne, and the Director-General of UNESCO, Koichiro Matsuura, will also welcome the participants. Terje Roed-Larsen, United Nations Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process and Personal Representative of the Secretary-General to the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the Palestinian Authority, will present the keynote address of the encounter, focusing on the peace process in the Middle East. -

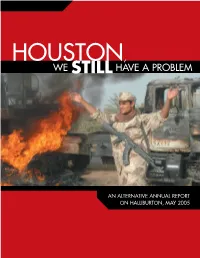

Houston, We Still Have a Problem

HOUSTON, WE STILL HAVE A PROBLEM AN ALTERNATIVE ANNUAL REPORT ON HALLIBURTON, MAY 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION II. MILITARY CONTRACTS III. OIL & GAS CONTRACTS IV. ONGOING INVESTIGATIONS AGAINST HALLIBURTON V. CORPORATE WELFARE & POLITICAL CONNECTIONS VI. CONCLUSIONS & RECOMMENDATIONS COVER: An Iraqi National Guard stands next to a burning US Army supply truck in the outskirts of Balad, Iraq. October 14, 2004. Photo by Asaad Muhsin, Associated Press HOUSTON, WE HAVE A PROBLEM HOUSTON, WE STILL HAVE A PROBLEM In the introduction to Halliburton’s 2004 annual report, chief executive officer David Lesar reports to Halliburton’s shareholders that despite the extreme adversity of 2004, including asbestos claims, dangerous work in Iraq, and the negative attention that sur- rounded the company during the U.S. presidential campaign, Halliburton emerged “stronger than ever.” Revenue and operating income have increased, and over a third of that revenue, an estimated $7.1 billion, was from U.S. government contracts in Iraq. In a photo alongside Lesar’s letter to the shareholders, he From the seat of the company’s legal representatives, the view smiles from a plush chair in what looks like a comfortable is of stacks of paperwork piling up as investigator after investi- office. He ends the letter, “From my seat, I like what I see.” gator demands documents from Halliburton regarding every- thing from possible bribery in Nigeria to over-billing and kick- People sitting in other seats, in Halliburton’s workplaces backs in Iraq. The company is currently being pursued by the around the world, lend a different view of the company, which continues to be one of the most controversial corporations in U.S. -

Network Against Islamophobia a Project of Jewish Voice for Peace

Network Against Islamophobia A Project of Jewish Voice for Peace Issue No. 2. December 2014 Welcome What JVP Chapters Stories & Strategies: Islamophobia in Hamas is ISIS? What’s in this Have Been Doing to Organizers Speak Out Social Media What People Are newsletter, what is the Challenge Islamophobia An Interview With A Picture Is Worth A Saying About Network Against Updates from Atlanta Bina Ahmad Thousand Words This Meme, Islamophobia, and how and New York City Page 5-7 Page 8 Islamophobia, and to contact us. Page 2-4 Israel Page 1 Page 9-11 Welcome to the 2nd issue of the newsletter for the Network Against Islamophobia (NAI), a project of Jewish Voice for Peace. Since we posted our first newsletter, we have been putting together resources that we hope will be useful both to JVP chapters and to other groups organizing against Islamophobia and anti-Arab racism: FAQs on U.S. Islamophobia & Israel Politics; Resources on Islamophobia & Anti-Arab Racism in the United States; and Challenging the Pamela Geller/American Freedom Defense Initiative (AFDI) Anti-Muslim Ads. Also, check out the Jews Against Islamophobia Coalition’s short video, Jews Recommit to Standing Against Islamophobia, which we’ve posted on the NAI website. This newsletter contains information about some of the organizing against Islamophobia that JVP chapters have been doing. It also highlights the links between Islamophobia and Israel’s latest military campaign in Gaza. In an interview for the newsletter, human rights lawyer and activist Bina Ahmad discusses the impact on the U.S. Muslim community of the summer’s assault and the connection between Islamophobia and Israeli and U.S. -

The Silent Revolution Within NATO Logistics: a Study in Afghanistan Fuel and Future Applications

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2012-12 The silent revolution within NATO logistics: a study in Afghanistan fuel and future applications Evans, Michael J. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/27827 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS THE SILENT REVOLUTION WITHIN NATO LOGISTICS: A STUDY IN AFGHANISTAN FUEL AND FUTURE APPLICATIONS by Michael J. Evans and Stephen W. Masternak December 2012 Thesis Co-Advisors: Keenan Yoho E. Cory Yoder Second Readers Brian Greenshields and Frank Giordano Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED December 2012 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS THE SILENT REVOLUTION WITHIN NATO LOGISTICS: A STUDY IN AFGHANISTAN FUEL AND FUTURE APPLICATIONS 6. AUTHOR(S) Michael J. Evans and Stephen W. Masternak 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. -

2017 Sustainability Report a Focus on What Is Important

Introduction Business Overview Operating with Integrity Operating Responsibly Caring About People Appendix A FOCUS ON WHAT IS IMPORTANT MESSAGE FROM OUR CEO 2017 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT KBR 2017 Sustainability Report | 1 Introduction Business Overview Operating with Integrity Operating Responsibly Caring About People Appendix TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Operating Responsibly Message from our CEO 3 Safety and Physical Security 20 Message from our former and current Health, Safety, Information Security 24 Security, Environment and Social Responsibility Supply Chain 26 Committee Chairs 4 Environment 27 Business Overview Caring About People Our Company 5 Employer of Choice 32 2017 Financial Performance 8 Inclusion and Diversity 34 Governance 9 Human Rights 35 Our Sustainability Focus 11 Community Engagement 36 Insights from our Stakeholders 12 Appendix Materiality 13 GRI Index 38 Operating with Integrity List of Global Memberships and Organizations 44 Business Ethics 16 Anti-Corruption 17 Regulatory Compliance 18 About this Report Information presented in this Sustainability Report covers the Company’s sustainability profile for environmental, social, and governance performance during calendar year January 1, 2017 to December 31, 2017. The report encompasses all business units owned by KBR, Inc. globally including joint ventures. All data should be assumed to be global and as of December 31, 2017, unless otherwise noted. An exception is our discussion of material topics on page 14, as we included this in 2018, to be in accordance with the Global Reporting Initiative (“GRI”) Standards Core. This report was published March 1, 2019. This report has been prepared in accordance with the GRI Standards: Core Option. As required, our content reports on KBR’s material topics and related impacts, as well as how these impacts are managed.