Re-Contextualizing the War on Terror

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phyllis Bennis

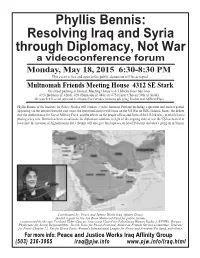

Phyllis Bennis: Resolving Iraq and Syria through Diplomacy, Not War a videoconference forum Monday, May 18, 2015 6:30-8:30 PM This event is free and open to the public; donations will be accepted. Multnomah Friends Meeting House 4312 SE Stark On-street parking is limited; Meeting House is 4-5 blocks from bus lines #15 (Belmont @ 42nd), #20 (Burnside @ 44th) or #75 (Cesar Chavez/39th @ Stark). Or watch it live on ustream.tv/channel/occucakes (remove ads using Firefox and AdBlockPlus) Phyllis Bennis of the Institute for Policy Studies will conduct a video forum in Portland including a question and answer period Appearing via the internet from the east coast, the renowned analyst will focus on the US War on ISIS (/Islamic State), the debate over the Authorization for Use of Military Force, and the effects on the people of Iraq and Syria of the US-led war-- in which Iran is playing a key role. Bennis has been an advocate for diplomatic solutions in light of the ongoing state of war the US has been in at least since the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001. Bennis will also give brief updates on Israel/Palestine and what's going on in Yemen. Coordinated by: Peace and Justice Works Iraq Affinity Group, funded in part by the Jan Bone Memorial Fund for public forums. cosponsored by Occupy Portland Elder Caucus, Americans United for Palestinian Human Rights (AUPHR), Oregon Physicians for Social Responsibility, Jewish Voice for Peace-Portland, American Friends Service Committee, Veterans for Peace Chapter 72, Pacific Green Party, Women's International League for Peace and Freedom-Portland, and others. -

Freedom Or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq Hannibal Travis

Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights Volume 3 | Issue 1 Article 4 Spring 2005 Freedom or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq Hannibal Travis Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr Recommended Citation Hannibal Travis, Freedom or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq, 3 Nw. J. Int'l Hum. Rts. 1 (2005). http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr/vol3/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Copyright 2005 Northwestern University School of Law Volume 3 (Spring 2005) Northwestern University Journal of International Human Rights FREEDOM OR THEOCRACY?: CONSTITUTIONALISM IN AFGHANISTAN AND IRAQ By Hannibal Travis* “Afghans are victims of the games superpowers once played: their war was once our war, and collectively we bear responsibility.”1 “In the approved version of the [Afghan] constitution, Article 3 was amended to read, ‘In Afghanistan, no law can be contrary to the beliefs and provisions of the sacred religion of Islam.’ … This very significant clause basically gives the official and nonofficial religious leaders in Afghanistan sway over every action that they might deem contrary to their beliefs, which by extension and within the Afghan cultural context, could be regarded as -

American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics

American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Nese F. DeBruyne Senior Research Librarian Updated September 14, 2018 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL32492 American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Summary This report provides U.S. war casualty statistics. It includes data tables containing the number of casualties among American military personnel who served in principal wars and combat operations from 1775 to the present. It also includes data on those wounded in action and information such as race and ethnicity, gender, branch of service, and cause of death. The tables are compiled from various Department of Defense (DOD) sources. Wars covered include the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican War, the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam Conflict, and the Persian Gulf War. Military operations covered include the Iranian Hostage Rescue Mission; Lebanon Peacekeeping; Urgent Fury in Grenada; Just Cause in Panama; Desert Shield and Desert Storm; Restore Hope in Somalia; Uphold Democracy in Haiti; Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF); Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF); Operation New Dawn (OND); Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR); and Operation Freedom’s Sentinel (OFS). Starting with the Korean War and the more recent conflicts, this report includes additional detailed information on types of casualties and, when available, demographics. It also cites a number of resources for further information, including sources of historical statistics on active duty military deaths, published lists of military personnel killed in combat actions, data on demographic indicators among U.S. military personnel, related websites, and relevant Congressional Research Service (CRS) reports. -

U. S. Foreign Policy1 by Charles Hess

H UMAN R IGHTS & H UMAN W ELFARE U. S. Foreign Policy1 by Charles Hess They hate our freedoms--our freedom of religion, our freedom of speech, our freedom to vote and assemble and disagree with each other (George W. Bush, Address to a Joint Session of Congress and the American People, September 20, 2001). These values of freedom are right and true for every person, in every society—and the duty of protecting these values against their enemies is the common calling of freedom-loving people across the globe and across the ages (National Security Strategy, September 2002 http://www. whitehouse. gov/nsc/nss. html). The historical connection between U.S. foreign policy and human rights has been strong on occasion. The War on Terror has not diminished but rather intensified that relationship if public statements from President Bush and his administration are to be believed. Some argue that just as in the Cold War, the American way of life as a free and liberal people is at stake. They argue that the enemy now is not communism but the disgruntled few who would seek to impose fundamentalist values on societies the world over and destroy those who do not conform. Proposed approaches to neutralizing the problem of terrorism vary. While most would agree that protecting human rights in the face of terror is of elevated importance, concern for human rights holds a peculiar place in this debate. It is ostensibly what the U.S. is trying to protect, yet it is arguably one of the first ideals compromised in the fight. -

American Exceptionalism at a Crossroads

American Exceptionalism at a Crossroads Seongjong Song The main goal of this research is to review and examine how the narrative of American exceptionalism has evolved over time, inter alia, in different admini- strations of the United States. The frequency in the usage of “American exceptionalism,” which came into use during the twentieth century, has increased exponentially for the last couple of years. The term, which began as a beacon of light and democracy as envisioned in John Winthrop’s “a City upon a Hill” in 1630 has undergone significant changes over the last four cen- turies. American exceptionalism has been used to justify a variety of purpos- es, from territorial expansion, Wilsonian idealism, a global crusade against an “Evil Empire,” to a preemptive strategy, and even as a political weapon for punishing opponents. Lastly, especially in view of the ongoing war on terror- ism, three prominent strands of American exceptionalism are discussed: exemplarism, expansionism and exemptionalism. Key Words: American exceptionalism, foreign policy, ‘shining city on a hill,’ Manifest Destiny, Wilsonianism, Ronald Reagan, Barack Obama, Bush Doctrine, exemplarism, expansionism, exemption- alism merican exceptionalism” is at a crossroads. What started out as a beacon “A of democracy and freedom in John Winthrop’s 1630 sermon “a City upon a Hill,” the term has evolved over a lengthy period of time spanning close to four centuries, during which it has been intermingled and imbued with distinct strands of narratives such as exemplarism, expansionism and exemptionalism. History came full circle when Russian President Vladimir Putin admonished President Obama for evoking “American exceptionalism” as a pretext to launch a military strike against Syria; a phrase, ironically, that had been invented by one *Seongjong Song ([email protected]) is a Visiting Professor at Chungnam National University. -

And Pale Odia Palestinian Woman in Jabaliya Camp, Gaza Strip

and Pale odia Palestinian woman in Jabaliya Camp, Gaza Strip. Her home was demolished by Israeli military, (p.16) (Photo: Neal Cassidy) nunTHE JOURNAL OF SUBSTANCE FOR PROGRESSIVE WOMEN VOL. XV SUMMER 1990 PUBLISHER/EDITOR IN CHIEF Merle Hoffman MANAGING EDITOR Beverly Lowy ASSOCIATE EDITOR Eleanor J. Bader ASSISTANT EDITOR Karen Aisenberg EDITOR AT LARGE Phyllis Chester CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Charlotte Bunch Vinie Burrows Naomi Feigelson Chase Irene Davall FEATURES Above: Goats on a porch at Toi Derricotte Mandala. All animals are treated with Roberta Kalechofsky BREAKING BARRIERS: affection and respect, even the skunks. Flo Kennedy WOMEN AND MINORITIES IN (p.10) (Photo: Helen M. Stummer) Fred Pelka THE SCIENCES Cover: A single mother and her Helen M. Stummer ON THE ISSUES interviews children find permanency in a H.O.M.E.- ART DIRECTORS Paul E. Gray, President of MIT, and built home. (Photo: Helen M. Stummer) Michael Dowdy Dean of Student Affairs, Shirley M. Julia Gran McBay, on sexism and racism in A SONG SO BRAVE — ADVERTISING AND SALES academia 7 PHOTO ESSAY DIRECTOR Text By Phyllis Chesler Carolyn Handel H.O.M.E. Photos By Joan Roth ONE WOMAN'S APPROACH Phyllis Chesler and an international ON THE ISSUES: A feminist, humanist TO SOCIETY'S PROBLEMS group of feminists present a Torah to publication dedicated to promoting By Helen M. Stummer political action through awareness and the women of Jerusalem 19 education; working toward a global Visual sociologist Helen M. Stummer political consciousness; fostering a spirit profiles a unique program to combat TO PEE OR NOT TO PEE of collective responsibility for positive homelessness, poverty and By Irene Davall social change; eradicating racism, disenfranchisement 10 A humorous recollection of the "pee- sexism, ageism, speciesism; and support- in" that forced Harvard to examine its ing the struggle of historically disenfran- FROM STONES TO sexism 20 chised groups to protect and defend STATEHOOD themselves. -

British Public Perception Towards Wars in Afghanistan and Iraq

Global Regional Review (GRR) URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/grr.2018(III-I).37 British Public Perception towards Wars in Afghanistan and Iraq Vol. III, No. I (2018) | Page: 503 ‒ 517 | DOI: 10.31703/grr.2018(III-I).37 p- ISSN: 2616-955X | e-ISSN: 2663-7030 | ISSN-L: 2616-955X This article seeks to explore the Aasima Safdar * Abstract perception of the British informants regarding the Afghanistan war 2001 and Iraq war Samia Manzoor † 2003. Heavy users of British media were interviewed. The present article adopts the qualitative approach Ayesha Qamar ‡ and ten in-depth interviews were conducted by the British informants. It was found that the British informants considered the 9/11 attacks as a tragic incident and Al Qaeda was held responsible for this. They supported their government’s policies to curb terrorism but they highly condemned human Key Words: causalities during the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. Particularly, they condemned their government’s Public perception, policy about Iraq war 2003. Regarding, the British British media, Iraq media coverage of these wars, there was mixed opinion. Some of them considered that British media war, Afghanistan gave biased coverage to the wars however; few war thought that media adopted a balanced approach. Overall, they stressed that the government should take responsible action against terrorism and human causalities should be avoided. Introduction September 11 attacks were immensely covered by the world media. The electronic channels reported the images of tragedy, popular personalities and the physical destructions (Monahan, 2010). Within a few hours of the tragedy, the TV screens were loaded with images of terrorist attacks. -

American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics

American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Updated July 29, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL32492 American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Summary This report provides U.S. war casualty statistics. It includes data tables containing the number of casualties among American military personnel who served in principal wars and combat operations from 1775 to the present. It also includes data on those wounded in action and information such as race and ethnicity, gender, branch of service, and cause of death. The tables are compiled from various Department of Defense (DOD) sources. Wars covered include the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican War, the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam Conflict, and the Persian Gulf War. Military operations covered include the Iranian Hostage Rescue Mission; Lebanon Peacekeeping; Urgent Fury in Grenada; Just Cause in Panama; Desert Shield and Desert Storm; Restore Hope in Somalia; Uphold Democracy in Haiti; Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF); Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF); Operation New Dawn (OND); Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR); and Operation Freedom’s Sentinel (OFS). Starting with the Korean War and the more recent conflicts, this report includes additional detailed information on types of casualties and, when available, demographics. It also cites a number of resources for further information, including sources of historical statistics on active duty military deaths, published lists of military personnel killed in combat actions, data on demographic indicators among U.S. military personnel, related websites, and relevant CRS reports. Congressional Research Service American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... -

U.S.-Pakistan Engagement: the War on Terrorism and Beyond

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Touqir Hussain While the war on terrorism may have provided the rationale for the latest U.S. engagement with Pakistan, the present relationship between the United States and Pakistan is at the crossroads of many other issues, such as Pakistan’s own U.S.-Pakistan reform efforts, America’s evolving strategic relationship with South Asia, democracy in the Muslim world, and the dual problems of religious extremism and nuclear proliferation. As a result, Engagement the two countries have a complex relationship that presents a unique challenge to their respective policymaking communities. The War on Terrorism and Beyond This report examines the history and present state of U.S.-Pakistan relations, addresses the key challenges the two countries face, and concludes with specific policy recommendations Summary for ensuring the relationship meets the needs • The current U.S. engagement with Pakistan may be focused on the war on terrorism, of both the United States and Pakistan. It was written by Touqir Hussain, a senior fellow at the but it is not confined to it. It also addresses several other issues of concern to the United States Institute of Peace and a former United States: national and global security, terrorism, nuclear proliferation, economic senior diplomat from Pakistan, who served as and strategic opportunities in South Asia, democracy, and anti-Americanism in the ambassador to Japan, Spain, and Brazil. Muslim world. • The current U.S. engagement with Pakistan offers certain lessons for U.S. -

Medical Discrimination in the Time of COVID-19: Unequal Access to Medical Care in West Bank and Gaza Hana Cooper Seattle University ‘21, B.A

Medical Discrimination in the Time of COVID-19: Unequal Access to Medical Care in West Bank and Gaza Hana Cooper Seattle University ‘21, B.A. History w/ Departmental Honors ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE A SYSTEM OF DISCRIMINATION COVID-19 IMPACT Given that PalestiniansSTRACT are suffering from As is evident from headlines over the last year, Palestinians are faring much worse While many see the founding of Israel in 1948 as the beginning of discrimination against COVID-19 has amplified all of the existing issues of apartheid, which had put Palestinians the COVID-19 pandemic not only to a under the COVID-19 pandemic than Israelis. Many news sources focus mainly on the Palestinians, it actually extends back to early Zionist colonization in the 1920s. Today, in a place of being less able to fight a pandemic (or any major, global crisis) effectively. greater extent than Israelis, but explicitly present, discussing vaccine apartheid and the current conditions of West Bank, Gaza, discrimination against Palestinians continues at varying levels throughout West Bank, because of discriminatory systems put into and Palestinian communities inside Israel. However, few mainstream news sources Gaza, and Israel itself. Here I will provide some examples: Gaza Because of the electricity crisis and daily power outages in Gaza, medical place by Israel before the pandemic began, have examined how these conditions arose in the first place. My project shows how equipment, including respirators, cannot run effectively throughout the day, and the it is clear that Israel is responsible for taking the COVID-19 crisis in Palestine was exacerbated by existing structures of Pre-1948 When the infrastructure of what would eventually become Israel was first built, constant disruptions in power cause the machines to wear out much faster than they action to ameliorate the crisis. -

Press Release United Nations Department of Public Information • News and Media Services Division • New York PAL/1887 PI/1354 13 June 2001

Press Release United Nations Department of Public Information • News and Media Services Division • New York PAL/1887 PI/1354 13 June 2001 DPI TO HOST INTKRNATIONAI, MEDIA ENCOUNTER ON QUESTION OF PALESTINE IN PARIS, 18 - 19 JUNE Search for Peace in Middle East, Role of United Nations To Be Discussed Prominent journalists and Middle East experts, including senior officials and lawmakers from Israel and the Palestinian Authority, will meet at the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) headquarters in Paris, on 18 and 19 June, at an international media encounter on the question of Palestine organized by the Department of Public Information (DPI). The overall theme of the encounter is "The search for peace in the Middle East". It is designed as a forum where media representatives and international experts will have an opportunity to discuss the status of the peace process, ways and means to break the deadlock, and the cycle of violence and reporting about the developments in the Middle East. They will also discuss the role of the United Nations in the question of Palestine and in the overall search for peace in the Middle East. The Secretary-General of the United Nations is expected to issue a message welcoming the participants, which will be delivered by Shashi Tharoor, Interim Head, DPI. The Secretary-General of the French Foreign Ministry, Loic Hennekinne, and the Director-General of UNESCO, Koichiro Matsuura, will also welcome the participants. Terje Roed-Larsen, United Nations Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process and Personal Representative of the Secretary-General to the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the Palestinian Authority, will present the keynote address of the encounter, focusing on the peace process in the Middle East. -

Whiteness After 9/11

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Washington University St. Louis: Open Scholarship Washington University Journal of Law & Policy Volume 18 Whiteness: Some Critical Perspectives January 2005 Whiteness After 9/11 Thomas Ross University of Pittsburgh Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy Part of the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Thomas Ross, Whiteness After 9/11, 18 WASH. U. J. L. & POL’Y 223 (2005), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol18/iss1/10 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Journal of Law & Policy by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Whiteness After 9/11 Thomas Ross I. INTRODUCTION Race is not a natural, self-evident, or timeless idea. It exists as a social construction. Its primary work is to express two parallel and intertwined conceptions—the inferiority of the non-White and the always corresponding superiority of the White race. If Blacks are lazy, Whites are implicitly industrious. If Blacks are prone to criminality, Whites are law-abiding. If Blacks are not patriotic, Whites are, and so on. When Whites who hold these racist ideas exercise discretion and power—as judges, police officers, employers, and so on—the Whites in their world receive an illicit boost, a presumption of worthiness and belonging. While many White Americans reject this terrible, unwanted boost, many other Americans, consciously or unconsciously, presume that racial differences are real and that being White makes them inherently superior to those deemed not White.