From Dictatorship to Democracy: Iraq Under Erasure Abeer Shaheen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

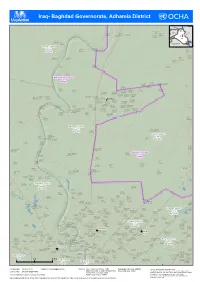

Iraq- Baghdad Governorate, Adhamia District

( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Iraq- Baghdad Governorate, Adham( ia District ( ( Turkey Mosul! ! Albu Blai'a Erbil village Syria Ahmad al Al-Hajiyah IQ-P12429 Mahmud al Iran ( Mahmud River Al Bu Algah Khamis Baghdad Jadida Qaryat Albu IQ-P09040 IQ-P12203 IQ-P12398 IQ-P12326 Ramadi! ( IQ-P12308 ( ( Tannom ( !\ IQ-P12525 Jordan Najaf! Basrah! Hay Masqat Jurf Al IQ-P12295 Milah Bohroz Mahbubiyah ( SIaQ-uPd12i 2A(32rabia KIQu-wP1a2i3t22 ( IQ-P08417 ( ( ( Mohamed sakran Tarmia District IQ-P12335 Rashdiyah Muhammad (Noor village) Um Al al Jeb اﻟطﺎرﻣﯾﺔ IQ-P08355 Rumman IQ-P08339 ( ( IQ-P12386 IQ-D045 ( Al Halfayah village - 3 Mehdi al Ahmad Jamil Abdul Karim IQ-P12171 Hasan ( ( IQ-P09041 IQ-P08224 ( ( Al A`baseen IQ-P12332 ( village IQ-P12157 ( Sayyid Ahwiz Muhammad Musa Agha IQ-P08231 IQ-P08360 ( ( IQ-P12339 ( ( (( ( ( Fatah Chraiky IQ-P08312 IQ-P08307 ( ( ( Baghdad Governorate ( ( ﺑﻐداد IQ-G07 Qaryat Al Mohamad Khedidan 1 ( Khalaf Tameem Sakran IQ-P12318 ( ( ( Al-Mahmoud IQ-P12349 ( ( Al A'tb(a IQ-P12334 (( IQ-P12313 ( ( Qaryat ( village ( ( Darwesha IQ-P12161 ( Khalaf al IQ-P12359 ( ( Ulwan Muhammad Ja`atah Ali al Hajj ( Hussayniya - al `Abd al `Abbas IQ-P08333 Al Hussayniya IQ-P08297 Mahala 224 IQ-P12385 ( ( ( ( Al Hussainiya (Mahala 222) IQ-P12337 Al Husayniya ( IQ-P08330 ( ( ( - Mahalla 221 - Mahalla 213 IQ-P08264 ( IQ-P08243 IQ-P08251 Al Hussainiya Hussayniya - Al Hussayniya ( ( - Mahalla 216 Mahala 218 - Mahalla 220 IQ-P08253 ( IQ-P08329 IQ-P08261 ( Mahmud al Abdul Aziz Hay Al Waqf Al Hussainiya - ( ( Qal`at Jasim `Ulaywi Hamadi -

The Resurgence of Asa'ib Ahl Al-Haq

December 2012 Sam Wyer MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 7 THE RESURGENCE OF ASA’IB AHL AL-HAQ Photo Credit: Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq protest in Kadhimiya, Baghdad, September 2012. Photo posted on Twitter by Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2012 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2012 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 Washington, DC 20036. http://www.understandingwar.org Sam Wyer MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 7 THE RESURGENCE OF ASA’IB AHL AL-HAQ ABOUT THE AUTHOR Sam Wyer is a Research Analyst at the Institute for the Study of War, where he focuses on Iraqi security and political matters. Prior to joining ISW, he worked as a Research Intern at AEI’s Critical Threats Project where he researched Iraqi Shi’a militia groups and Iranian proxy strategy. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Political Science from Middlebury College in Vermont and studied Arabic at Middlebury’s school in Alexandria, Egypt. ABOUT THE INSTITUTE The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) is a non-partisan, non-profit, public policy research organization. ISW advances an informed understanding of military affairs through reliable research, trusted analysis, and innovative education. ISW is committed to improving the nation’s ability to execute military operations and respond to emerging threats in order to achieve U.S. -

David Rocco's Dolce Vita Canada 2004-2015 Format: Series (30') 65X30 Min + Holiday Special: 60 Min Genre: Documentary

Breaking Wild Canada 2020 Format: Series (60') 10x60 Genre: Documentary Director: Jimmy Lulua Cast: Howard Lulua; Amanda Lulua; Emery Philipps Synopsis: Breaking Wild is a thrilling action-adventure series that follows a crack team of local cowboys, ex-pat American settlers and expert horse trainers united in a high-octane mission to save the majestic herd of wild horses that roams B.C.’s pristine Nemiah Valley. It is a wild ride that demands limitless courage, nerves of steel, and a love of the chase. From the producer of MANTRACKER. Evolution of Driving 2020 Format: Series (60') 10x60' Genre: Documentary Director: Cast: Jochen Mass; Nico Rosberg; Doreen Seidl; Martin Utberg; Walter Röhrl; Adrian Sutil Synopsis: Italian power cars, German masterpieces, and British Beauties by Ferrari, Mercedes, Aston Martin, Porsche, Jaguar, Rolls Royce and Lamborghini: EVOLUTION OF DRIVING - the sophisticated car magazine - shows the history, the present and the future of the automobiles of the world´s most important manufacturers. In the 20th century, the automobile become the epidome of mobility for mankind and therefore its constant companion. Mobility has become the motor of change. Cars are masterpieces of technology. Unique racing machines, vehicles built for adventure. Racing Legends and international automobile ... Hollywood Homicide Uncovered Canada/USA 2016 Format: Non-Fiction Series (6x60‘) Genre: True Crime Director: Michael Sheehan Cast: Robert Blake, OJ Simpson, Phil Spector, Dorothy Stratten Synopsis: Hollywood Homicide Uncovered tells the story of unthinkable murders, all connected to the pursuit of celebrity. Each hour-long episode uncovers the real-life drama, deceit and crime itself, against the backdrop of a city where dreams are supposed to come true. -

Importance of Recycling Construction and Demolition Waste

WMCAUS IOP Publishing 245 IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering1234567890 (2017) 082062 doi:10.1088/1757-899X/245/8/082062 Postwar City: Importance of Recycling Construction and Demolition Waste Hanan Al-Qaraghuli, Yaman Alsayed, Ali Almoghazy Master's degree students at the Technical University of Berlin Campus El Gouna, Department of Urban Development [email protected] Abstract - Wars and armed conflicts have heavy tolls on the built environment when they take place in cities. It is not only restricted to the actually fighting which destroys or damages buildings and infrastructure, but the damage and destruction inflicts its impacts way beyond the cessation of military actions. They can even have another impact through physical segregation of city quarters through walls and checkpoints that complicates, or even terminates, mobility of citizens, goods, and services in the post-war scenario. The accumulation of debris in the streets often impedes the processes of rescue, distribution of aid and services, and other forms of city life as well. Also, the amount of effort and energy needed to remove those residual materials to their final dumping sites divert a lot of urgently needed resources. In this paper, the components of construction and demolition waste found in post-war cities are to be discussed, relating each one to its origins and potential reuses. Then the issues related to the management of construction waste and demolition debris resulting from military actions are to be discussed. First, an outlook is to be given on the historical example of Berlin and how the city was severely damaged during World War II, and how the reconstruction of the city was aided in part by the reuse of demolition debris. -

Rebooting U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq

Rebooting U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq MICHAEL KNIGHTS POLICY FOCUS 137 Rebooting U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq MICHAEL KNIGHTS THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Washington Institute, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2015 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Design: 1000colors Photo: A Kurdish fighter keeps guard while overlooking positions of Islamic State mili- tants near Mosul, northern Iraq, August 2014. (REUTERS/Youssef Boudlal) CONTENTS Acknowledgments | v Acronyms | vi Executive Summary | viii 1 Introduction | 1 2 Federal Government Security Forces in Iraq | 6 3 Security Forces in Iraqi Kurdistan | 26 4 Optimizing U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq | 39 5 Issues and Options for U.S. Policymakers | 48 About the Author | 74 TABLES 1 Effective Combat Manpower of Iraq Security Forces | 8 2 Assessment of ISF and Kurdish Forces as Security Cooperation Partners | 43 FIGURES 1 ISF Brigade Order of Battle, January 2015 | 10 2 Kurdish Brigade Order of Battle, January 2015 | 28 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My thanks to a range of colleagues for their encouragement and assistance in the writing of this study. -

Thursday Friday

3:00 PM – 4:00 PM Thursday 4:00 PM – 5:00 PM 12:00 PM – 1:00 PM “Hannibal and the Second Punic War” “The History of War Gaming” Speaker: Nikolas Lloyd Location: Conestoga Room Speaker: Paul Westermeyer Location: Conestoga Room Description: The Second Punic War perhaps could have been a victory for Carthage, and today, church services and degree Description: Come learn about the history of war gaming from its certificates would be in Punic and not in Latin. Hannibal is earliest days in the ancient world through computer simulations, considered by many historians to be the greatest ever general, and focusing on the ways commercial wargames and military training his methods are still studied in officer-training schools today, and wargames have inspired each other. modern historians and ancient ones alike marvel at how it was possible for a man with so little backing could keep an army made 1:00 PM – 2:00 PM up of mercenaries from many nations in the field for so long in Rome's back yard. Again and again he defeated the Romans, until “Conquerors Not Liberators: The 4th Canadian Armoured Division in the Romans gave up trying to fight him. But who was he really? How Germany, 1945” much do we really know? Was he the cruel invader, the gallant liberator, or the military obsessive? In the end, why did he lose? Speaker: Stephen Connor, PhD. Location: Conestoga Room Description: In early April 1945, the 4th Canadian Armoured Division 5:00 PM – 6:00 PM pushed into Germany. In the aftermath of the bitter fighting around “Ethical War gaming: A Discussion” Kalkar, Hochwald and Veen, the Canadians understood that a skilled enemy defending nearly impassable terrain promised more of the Moderator: Paul Westermeyer same. -

Blood and Ballots the Effect of Violence on Voting Behavior in Iraq

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Göteborgs universitets publikationer - e-publicering och e-arkiv DEPTARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE BLOOD AND BALLOTS THE EFFECT OF VIOLENCE ON VOTING BEHAVIOR IN IRAQ Amer Naji Master’s Thesis: 30 higher education credits Programme: Master’s Programme in Political Science Date: Spring 2016 Supervisor: Andreas Bågenholm Words: 14391 Abstract Iraq is a very diverse country, both ethnically and religiously, and its political system is characterized by severe polarization along ethno-sectarian loyalties. Since 2003, the country suffered from persistent indiscriminating terrorism and communal violence. Previous literature has rarely connected violence to election in Iraq. I argue that violence is responsible for the increases of within group cohesion and distrust towards people from other groups, resulting in politicization of the ethno-sectarian identities i.e. making ethno-sectarian parties more preferable than secular ones. This study is based on a unique dataset that includes civil terror casualties one year before election, the results of the four general elections of January 30th, and December 15th, 2005, March 7th, 2010 and April 30th, 2014 as well as demographic and socioeconomic indicators on the provincial level. Employing panel data analysis, the results show that Iraqi people are sensitive to violence and it has a very negative effect on vote share of secular parties. Also, terrorism has different degrees of effect on different groups. The Sunni Arabs are the most sensitive group. They change their electoral preference in response to the level of violence. 2 Acknowledgement I would first like to thank my advisor Dr. -

Hard Offensive Counterterrorism

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2019 The Use of Force: Hard Offensive Counterterrorism Daniel Thomas Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the International Relations Commons Repository Citation Thomas, Daniel, "The Use of Force: Hard Offensive Counterterrorism" (2019). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 2101. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/2101 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE USE OF FORCE: HARD OFFENSIVE COUNTERTERRORISM A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By DANIEL THOMAS B.A., The Ohio State University, 2015 2019 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Defense Date: 8/1/19 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Daniel Thomas ENTITLED The Use of Force: Hard Offensive Counterterrorism BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts. _______________________ Vaughn Shannon, Ph.D. Thesis Director ________________________ Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. Director, Master of Arts Program in International and Comparative Politics Committee on Final Examination: ___________________________________ Vaughn Shannon, Ph.D. School of Public and International Affairs ___________________________________ Liam Anderson, Ph.D. School of Public and International Affairs ___________________________________ Pramod Kantha, Ph.D. School of Public and International Affairs ______________________________ Barry Milligan, Ph.D. -

Bremer's Gordian Knot: Transitional Justice and the US Occupation of Iraq Eric Stover Berkeley Law

Berkeley Law Berkeley Law Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2005 Bremer's Gordian Knot: Transitional Justice and the US Occupation of Iraq Eric Stover Berkeley Law Hanny Megally Hania Mufti Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/facpubs Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Bremer's Gordian Knot: Transitional Justice and the US Occupation of Iraq, 27 Hum. Rts. Q. 830 (2005) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Berkeley Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Berkeley Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HUMAN RIGHTS QUARTERLY Bremer's "Gordian Knot": Transitional Justice and the US Occupation of Iraq Eric Stover,* Hanny Megally, ** & Hania Mufti*** ABSTRACT Shortly after the US invasion and occupation of Iraq, L. Paul Bremer III, in his capacity as the chief administrator of the Coalition Provisional Author- ity (CPA), introduced several transitional justice mechanisms that set the *Eric Stover is Director of the Human Rights Center at the University of California, Berkeley, and Adjunct Professor in the School of Public Health. In 1991, Stover led a team of forensic scientists to northern Iraq to investigate war crimes committed by Iraqi troops during the Anfal campaign against the Kurds in the late 1980s. In March and April 2003, he returned to northern Iraq where he and Hania Mufti monitored the compliance with the 1949 Geneva Conventions by all sides to the conflict. He returned to Iraq in February 2004 to assist Mufti in investigating the status of documentary and physical evidence to be used in trials against Saddam Hussein and other members of the Ba'athist Party. -

The Search for Post-Conflict Justice in Iraq: a Comparative Study of Transitional Justice Mechanisms and Their Applicability to Post-Saddam Iraq, 33 Brook

Brooklyn Journal of International Law Volume 33 | Issue 1 Article 2 2007 The eS arch for Post-Conflict Justice in Iraq: A Comparative Study of Transitional Justice Mechanisms and Their Applicability to Post- Saddam Iraq Dana M. Hollywood Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil Recommended Citation Dana M. Hollywood, The Search for Post-Conflict Justice in Iraq: A Comparative Study of Transitional Justice Mechanisms and Their Applicability to Post-Saddam Iraq, 33 Brook. J. Int'l L. (2007). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil/vol33/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. THE SEARCH FOR POST-CONFLICT JUSTICE IN IRAQ: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE MECHANISMS AND THEIR APPLICABILITY TO POST- SADDAM IRAQ Dana Michael Hollywood* INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................60 I. TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE .......................................................................63 A. Conceptual Overview .....................................................................63 B. Retributive v. Restorative Justice ...................................................67 C. Truth v. Justice...............................................................................69 1. Truth: A Right to Disclosure?.....................................................70 a. Is -

Dora – Baghdad – Government Employees – Forced Relocation – Kurdish Areas – Housing

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: IRQ31805 Country: Iraq Date: 22 May 2007 Keywords: Iraq – Kurds – Shia – Dora – Baghdad – Government employees – Forced relocation – Kurdish areas – Housing This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Are insurgent/terrorist groups in Iraq targeting anyone who works alongside the pro- coalition forces in the rebuilding of Iraq? 2. Are they targeting Iraqi government workers who perform a co-ordinating role in this regard? 3. Do the insurgents target Shia Iraqis? 4. What is the level of instability within Dora for Kurdish Shiites? 5. Are Kurdish Shiites from Dora being forced to relocate from Dora? 6. Can Kurdish Shiites from Dora safely relocate elsewhere in Baghdad? 7. Can Kurdish Shiites safely relocate to the Kurdish areas of Iraq? 8. Are the local authorities in the Kurdish region imposing regulations to limit the influx of refugees from other parts of Iraq? 9. What has the impact of these internal refugees had on housing and rent in the Kurdish region? RESPONSE 1. Are insurgent/terrorist groups in Iraq targeting anyone who works alongside the pro-coalition forces in the rebuilding of Iraq? 2. Are they targeting Iraqi government workers who perform a co-ordinating -

UN Assistance Mission for Iraq ﺑﻌﺜﺔ اﻷﻣﻢ اﻟﻤﺘﺤﺪة (UNAMI) ﻟﺘﻘﺪﻳﻢ اﻟﻤﺴﺎﻋﺪة

ﺑﻌﺜﺔ اﻷﻣﻢ اﻟﻤﺘﺤﺪة .UN Assistance Mission for Iraq 1 ﻟﺘﻘﺪﻳﻢ اﻟﻤﺴﺎﻋﺪة ﻟﻠﻌﺮاق (UNAMI) Human Rights Report 1 January – 31 March 2007 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS..............................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................................2 SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................................2 PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS.......................................................................................................4 EXTRA-JUDICIAL EXECUTIONS AND TARGETED AND INDISCRIMINATE KILLINGS .........................................4 EDUCATION SECTOR AND THE TARGETING OF ACADEMIC PROFESSIONALS ................................................8 FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION .........................................................................................................................10 MINORITIES...............................................................................................................................................13 PALESTINIAN REFUGEES ............................................................................................................................15 WOMEN.....................................................................................................................................................16 DISPLACEMENT