Annual Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rakhine State Census Report Volume 3 – K

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Rakhine State Census Report Volume 3 – K Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Rakhine State Report Census Report Volume 3 – K For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014, and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is now my hope that the main results, both Union and each of the State and Region reports, will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national and sub-national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and officers at the State/Region, District and Township Levels, and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. The technical support and our strong desire to follow international standards affirmed our commitment to strict adherence to the guidelines and recommendations, which form part of international best practices for census taking. -

National Report of Myanmar

1 NATIONAL REPORT OF MYANMAR On the Sustainable Management of The Bay of Bengal Large Marine Ecosystem (BOBLME) GCP/RAS/179/WBG Department of Fisheries Fishing Grounds of Myanmar and Landing Sites 92 30’ 93 30’ 94 30’ 95 30’ 96 30’ 97 30’ 98 30’ 99 a 1 SITTWAY T O EN F F A1 A2 M IS T H R 20 E 20 A R P I E E A3 A4 b A5 A6 S D 30’ 30’ c A10 A7 A8 A9 19 19 d A14 THANDWE A11 A12 A13 A15 30’ HANDWETHANDWE 30’ e A16 A17 A18 A19 A20 A 18 2 18 B1 B2 B3 B4 B5 GWA 30’ f 30’ B6 B7 B8 B9 B10 17 g 17 YANGON B11 B12 B13 B14 B15 PATHEIN 30’ h 30’ i B20 B16 B17 B18 B19 D2 D3 B j D1 3 16 16 4 C3 C1 C2 k C4 C5 D4 D5 D6 D7 D8 30’ BAS 30’ E L I NE YE C6 C7 C8 C9 C10 D9 D10 D11 D12 D13 TER RITO 15 15 RIA L LI NE YE C11 C12 C13 C14 C15 D14 D15 D16 D17 D18 30’ 30’ l C16 C17 C18 C19 C20 D19 D20 D21 D22 D23 DAWEI 14 C m 14 5 C21 C22 C23 C24 8 9 6 C25 D24 D25 D26 D27 D28 D D 29 30’ 7 10 30’ E1 E2 E3 E4 E5 E6 13 13 11 E8 E9 E10 n E11 E12 E7 30’ 30’ o MYEIK 12 MYEIK E13 E14 E15 E16 E17 E18 12 p 12 q 13 E20 E21 E22 E23 E24 E25 E 30’ 14 30’ F F2 F5 F7 1 F3 F4 F6 11 11 15 F F9 F10 F11 F12 F13 F14 r 30’ 8 30’ s 16 F 15 17 F16 F17 F18 F19 F20 F21 F 10 18 10 t KAWTHOUNG u v 92 30’ 93 30’ 94 30’ 95 30’ 96 30’ 97 30’ 98 30’ 99 Prepared by Myint Pe (National Consultant) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. -

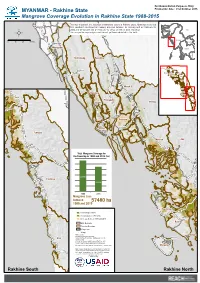

Mangrove Coverage Evolution in Rakhine State 1988-2015

For Humanitarian Purposes Only MYANMAR - Rakhine State Production date : 21st October 2015 Mangrove Coverage Evolution in Rakhine State 1988-2015 This map illustrates the evolution of mangrove extent in Rakhine State, Myanmar as derived Bhutan from Landsat-5 multispectral imagery acquired between 13 January and 23 February for Nepal Mindat 1988 and 30 January and 24 February for 2015 at 30m of pixel resolution. India China Town Bangladesh Bangladesh This is a preliminary analysis and has not yet been validated in the field. Paletwa Town Viet Nam Myanmar 0 10 20 30 Kms Laos Taungpyoletwea Kanpetlet Town Town Maungdaw Thailand Buthidaung Kyauktaw Cambodia Taungpyoletwea Maungdaw Kyauktaw Buthidaung Town Buthidaung Kyauktaw Maungdaw Kyauktaw Buthidaung Mrauk-U Town Maungdaw Rathedaung Mrauk-U Ponnagyun Town Minbya Rathedaung Ponnagyun Pauktaw Minbya Sittwe Pauktaw Myebon Sittwe Myebon Ann Ann Mrauk-U Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Kyaukpyu Ramree Ramree Toungup Rathedaung Mrauk-U Munaung Munaung Toungup Town Ann Thandwe Ponnagyun Thandwe Rathedaung Minbya Kyeintali Mindon Ma-Ei Town Town Town Gwa Gwa Ramree Minbya Town Ponnagyun Town Pauktaw Sittwe Pauktaw Town Sittwe Toungup Town Myebon Town Myebon Ann Toungup Town Total Mangrove Coverage for the Township in 1988 and 2015 (ha) Ann Town Thandwe Town 280986 Thandwe 223506 Kyaukpyu 1988 2015 Town Mangrove Loss between 57480 ha 1988 and 2015 Kyaukpyu New Mangrove area Kyeintali Town Remaining area 1988-2015 Ramree Decrease between 1988 and 2015 Town Ramree State Boundary Township Boundary Village-Tract Village Data sources: Toungup Landcover Analysis: UNOSAT Administrative Boundaries, Settlements: OCHA Munaung Gwa Town Roads: OSM Coordinate System: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 46N Contact: [email protected] File: REACH_MMR_Map_Rakhine_HVA_Mangrove_21OCT2015_A1 Munaung Note: Data, designations and boundaries contained Gwa Town on this map are not warranted to be error-free and do not imply acceptance by the REACH partners, associated, donors mentioned on this map. -

Zootaxa, Danio Aesculapii, a New Species of Danio

Zootaxa 2164: 41–48 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Danio aesculapii, a new species of danio from south-western Myanmar (Teleostei: Cyprinidae) SVEN O. KULLANDER & FANG FANG Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Swedish Museum of Natural History, PO Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract Danio aesculapii, new species, is described from small rivers on the western slope of the Rakhine Yoma in south-western Myanmar. It is superficially similar to D. choprae from northern Myanmar in having a series of vertical bars anteriorly on the side, but differs from it and other species of Danio in having six instead of seven or more branched dorsal-fin rays, and from all other species of Danio except D. erythromicron and D. kerri in having 12 instead of 10 or 14 circumpeduncular scale rows. Key words: Rakhine Yoma, Thandwe, Danio choprae, endemism Introduction The cyprinid fish genus Danio Hamilton includes 14 small species in South and Southeast Asia (Kullander et al. 2009), as a rule diagnosable by distinct species-specific colour patterns. About half of the species of Danio have a pigment pattern that consists of one or more dark or light horizontal stripes (Fang, 1998). Among the others, Danio kyathit Fang differs in having the stripes broken up into rows of small brown spots, D. margaritatus (Roberts) has a pattern of small light spots on the sides, D. dangila (Hamilton) has rows of dark rings with light centres, and D. -

Rakhine State, Myanmar

World Food Programme S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 Photographs: ©FAO/F. Del Re/L. Castaldi and ©WFP/K. Swe. This report has been prepared by Monika Tothova and Luigi Castaldi (FAO) and Yvonne Forsen, Marco Principi and Sasha Guyetsky (WFP) under the responsibility of the FAO and WFP secretariats with information from official and other sources. Since conditions may change rapidly, please contact the undersigned for further information if required. Mario Zappacosta Siemon Hollema Senior Economist, EST-GIEWS Senior Programme Policy Officer Trade and Markets Division, FAO Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific, WFP E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org at the following URL address: http://www.fao.org/giews/ The Global Information and Early Warning System on Food and Agriculture (GIEWS) has set up a mailing list to disseminate its reports. To subscribe, submit the Registration Form on the following link: http://newsletters.fao.org/k/Fao/trade_and_markets_english_giews_world S P E C I A L R E P O R T THE 2018 FAO/WFP AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY MISSION TO RAKHINE STATE, MYANMAR 12 July 2019 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Rome, 2019 Required citation: FAO. -

Annex 3 Public Map of Rakhine State

ICC-01/19-7-Anx3 04-07-2019 1/2 RH PT Annex 3 Public Map of Rakhine State (Source: Myanmar Information Management Unit) http://themimu.info/sites/themimu.info/files/documents/State_Map_D istrict_Rakhine_MIMU764v04_23Oct2017_A4.pdf ICC-01/19-7-Anx3 04-07-2019 2/2 RH PT Myanmar Information Management Unit District Map - Rakhine State 92° EBANGLADESH 93° E 94° E 95° E Pauk !( Kyaukhtu INDIA Mindat Pakokku Paletwa CHINA Maungdaw !( Samee Ü Taungpyoletwea Nyaung-U !( Kanpetlet Ngathayouk CHIN STATE Saw Bagan !( Buthidaung !( Maungdaw District 21° N THAILAND 21° N SeikphyuChauk Buthidaung Kyauktaw Kyauktaw Kyaukpadaung Maungdaw Mrauk-U Salin Rathedaung Mrauk-U Minbya Rathedaung Ponnagyun Mrauk-U District Sidoktaya Yenangyaung Minbya Pwintbyu Sittwe DistrictPonnagyun Pauktaw Sittwe Saku !( Minbu Pauktaw .! Ngape .! Sittwe Myebon Ann Magway Myebon 20° N RAKHINE STATE Minhla 20° N Ann MAGWAY REGION Sinbaungwe Kyaukpyu District Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Kyaukpyu !( Mindon Ramree Toungup Ramree Kamma 19° N 19° N Bay of Bengal Munaung Toungup Munaung Padaung Thandwe District BAGO REGION Thandwe Thandwe Kyangin Legend .! State/Region Capital Main Town !( Other Town Kyeintali !( 18° N Coast Line 18° N Map ID: MIMU764v04 Township Boundary Creation Date: 23 October 2017.A4 State/Region Boundary Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 International Boundary Data Sources: MIMU Gwa Base Map: MIMU Road Boundaries: MIMU/WFP Kyaukpyu Place Name: Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) Gwa translated by MIMU Maungdaw Mrauk-U Email: [email protected] Website: www.themimu.info Sittwe Ngathaingchaung Copyright © Myanmar Information Management Unit Kilometers !( Thandwe 2017. May be used free of charge with attribution. 0 15 30 60 Yegyi 92° E 93° E 94° E 95° E Disclaimer: The names shown and the boundaries used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.. -

Demographic Characteristic S and Road Network on the Spread of Coronavirus Pandemic in Rakhine State

THE IMPACT OF DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS AND ROAD NETWORK ON THE SPREAD OF CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC IN RAKHINE STATE: USING GEOSPATIAL TECHNIQUES Mu Mu Than (1), Khin Mar Yee (2), Tin Tin Mya (3), Thida Win (4) 1 Sittway University, Rakhine State, Myanmar 2 Myeik University, Tanintharyi Region, Myanmar 3 Pathein University, Ayeyarwady Region, Myanmar 4 East Yangon University, Yangon Region, Myanmar [email protected] KEY WORDS: connectivity, demographic characteristics, confirmed cases, factor 1. INTRODUCTION analysis, interaction Rakhine State has 5 districts in which 17 ABSTRACT: Demographic characteristics townships and 3sub-townships are included. give communities information for the past, Percentage of urban population is 17%. It has present and future plan and services. more rural nature. Total number of population Demographic data and connectivity of road in Rakhine State is 3,188,807 (2014 Census). It has an area of 36,778.1 Km2. Population network impact how far people travel and 2 what they do. The spread of COVID-19 cases density is 86.7 per km . It faces the Bay of in the state deals with these data. Bengal on the west, Bangladesh in the northwest and the India in the north. In the In the 31st August 2020 COVID-19 east it is bordered by state and regions of the confirmed cases across the state had risen to country (Figure 1). Waterway is important to 350 cases. This is more than that of Yangon the transportation of people and goods in the Region. The researchers are interested in the middle and northern part of the states to reasons for that. -

Report of Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar

A/HRC/39/64 Advance Edited Version Distr.: General 12 September 2018 Original: English Human Rights Council Thirty-ninth session 10–28 September 2018 Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Report of the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar* Summary The Human Rights Council established the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar in its resolution 34/22. In accordance with its mandate, the mission focused on the situation in Kachin, Rakhine and Shan States since 2011. It also examined the infringement of fundamental freedoms, including the rights to freedom of expression, assembly and peaceful association, and the question of hate speech. The mission established consistent patterns of serious human rights violations and abuses in Kachin, Rakhine and Shan States, in addition to serious violations of international humanitarian law. These are principally committed by the Myanmar security forces, particularly the military. Their operations are based on policies, tactics and conduct that consistently fail to respect international law, including by deliberately targeting civilians. Many violations amount to the gravest crimes under international law. In the light of the pervasive culture of impunity at the domestic level, the mission finds that the impetus for accountability must come from the international community. It makes concrete recommendations to that end, including that named senior generals of the Myanmar military should be investigated and prosecuted in an international criminal tribunal for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. * The present report was submitted after the deadline in order to reflect the most recent developments. A/HRC/39/64 Contents Page I. -

Gwa Township Report

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census RAKHINE STATE, THANDWE DISTRICT Gwa Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population October 2017 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Rakhine State, Thandwe District Gwa Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population Office No.48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431062 www.dop.gov.mm October 2017 Figure 1: Map of Rakhine State, showing the townships Gwa Township Figures at a Glance 1 Total Population 42,434 2 Population males 21,158 (49.9%) Population females 21,276 (50.1%) Percentage of urban population 22.4% Area (Km2) 1,489.3 3 Population density (per Km2) 28.5 persons Median age 31.8 years Number of wards 3 Number of village tracts 21 Number of private households 11,245 Percentage of female headed households 14.1% Mean household size 3.7 persons 4 Percentage of population by age group Children (0 – 14 years) 24.8% Economically productive (15 – 64 years) 66.3% Elderly population (65+ years) 8.9% Dependency ratios Total dependency ratio 50.9 Child dependency ratio 37.4 Old dependency ratio 13.5 Ageing index 36.0 Sex ratio (males per 100 females) 99 Literacy rate (persons aged 15 and over) 95.6% Male 97.2% Female 94.1% People with disability Number Per cent Any form of disability 1,679 4.0 Walking 788 1.9 Seeing 835 2.0 Hearing 565 1.3 Remembering 623 1.5 Type of Identity Card (persons aged 10 and over) Number Per cent Citizenship Scrutiny 25,941 72.4 Associate Scrutiny * -

Thandwe Kyeintali Bay of Bengal

(! Myanmar Information Management Unit Village Tracts of Thandwe Township Rakhine State TOUNGUP Auk Nat Maw Hpa Yar Maw Ü Kha Maung Tone Shwe Hlay Nat Maw Gwayt Chaung Sin Gaung Kyun Pauk Pwint Hpyay Ah Lel Hmyawt Wan Kyet Sar Kha Yan Chaung Taung Nyo Taung Nyo Maw Kin Maw Pyayt Wa Zee Kone Yae Kauk U Yin Pyin Kyaung Taik Let Pan Gawt Su Chan Pyin Ta Yaw Taw Shwe Me Kyaung Kyun Lin Mu Taung Pyin Hmo Hin An Taw PADAUNG Pyin Shin Aung Shwe Hlaw Zee Hpyu Kone (!Thandwe Urban Ta Lin Seik U Yin Kwin Nan Pa De Kaw Chaung Lin Thar Kyauk Tan Thar Yar Kwin Boe Wa Kone Ah Htu Mya Pyin Gon Min Chaung Me Nei Kwin Sat Lel Hmyaw Than Pu Yar KYANGIN Tha Yet Pin Kwin Kayin Kwin Ka Nyin Kone Ka Na Kho Kywe Thauk Kyauk Ka Lat THANDWE Pein Taw Gyi Maw Yon Kyee Kan Kyauk Gyi Pauk Tu Kyar Nyo Thit Ngoke To Wet Htee Taung Tone Taw Bay of Bengal Pa Zun Hpay Pyin Ma Khon Chin Mandalay MYANAUNG Magway !(Kyeintali Rakhine KYEINTALI Bago Bay of Bengal Kilometers 0 5 10 20 Ayeyarwady Yangon Data Sources : Map ID: MIMU250v01 .! State Capital Road Village Tract Area INGAPU Ba Win (Let PBaAn KShEon M) AP - MIMU Creation Date: 19 December 2011. A3 (! Main Town River and Stream Water Body Boundaries - WFP/MIMU/UNICEF Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 !( Other Town Township Boundary Place names - Ministry of Home Affair District Boundary Map produced by the MIMU - [email protected] (GAD) translated by MIMU State Boundary Website : http://www.themimu.info Disclaimer: The names shown and the boundaries used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.. -

TECHNICAL FINAL REPORT (Reporting Period: 16 February 2015 to 28 February, 2016)

Forest and Farm Facility (FFF) TECHNICAL FINAL REPORT (Reporting Period: 16 February 2015 to 28 February, 2016) Name of the Implementing Organization: Myanmar Environment Rehabilitation-conservation Network (MERN) I. Title of the project: Establishment of Regional level Community Forest Products Producer Association in Rakhine, Supporting MERN Membership Process for Forest and Farm Producer Groups and Developing an Effective Communication and Engagement Strategy II. Description of the site where the project was implemented: The project was implemented in Southern Rakhine State, specifically based in Gwa township and Kyeintali sub-township where MERN implemented a project from 2011 to 2014. Gwa and Kyeintali are situated in Rakhine State of Myanmar (see annex-1). The project area is one of the less developing regions in Rakhine State which is also less developed compare to other states and divisions in Myanmar. Food security and livelihood conditions are, although, not the worst due to not too much dense population but it is still far from satisfactory level. Coastal mangrove forests which are nesting place for fish, prawn, etc., wood and energy source for local people and also contributing for Disaster Risk Reduction are degrading at alarming rate in southern part of Rakhine. Gwa Township covers the total area of 885.11 sq.miles in which Kyein-ta-li Sub-township contributes 300.08 sq. miles. Over 75% of the area in Gwa Township is covered with forest, total extent of 434,592 acres, including mangrove area. According to the forest management classification by Forest Department there is, although, no Reserved Forest in Gwa, two Protected Public Forests are existed and the others are Public Forest. -

Hazard Profile of Myanmar: an Introduction 1.1

Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................ I List of Figures ................................................................................................................ III List of Tables ................................................................................................................. IV Acronyms and Abbreviations ......................................................................................... V 1. Hazard Profile of Myanmar: An Introduction 1.1. Background ...................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Myanmar Overview ......................................................................................................... 2 1.3. Development of Hazard Profile of Myanmar : Process ................................................... 2 1.4. Objectives and scope ....................................................................................................... 3 1.5. Structure of ‘Hazard Profile of Myanmar’ Report ........................................................... 3 1.6. Limitations ....................................................................................................................... 4 2. Cyclones 2.1. Causes and Characteristics of Cyclones in the Bay of Bengal .......................................... 5 2.2. Frequency and Impact ....................................................................................................