The Library of 'Flesh': a Return to Bodily Perception

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palace-House-Brochure-FINAL-Mar

PALACE HOUSE 3 CATHEDRAL STREET SOUTH BANK SE1 Prime long let freehold investment opportunity Contents INVESTMENT Summary 04 / 05 Location 06 / 13 Connectivity 14 / 15 Local Occupiers 16 / 19 Local DEVELOPMENT pIPELINE 20 / 21 Description 24 / 25 Specification 26 Accommodation 27 Floor Plans 28 / 29 Tenure and TENANCY 30 / 31 Covenant Information 32 Asset Management 33 SOUTH BANK MARKET 34 / 35 Contact & FURTHER INFORMATION 36 / 37 01-02 INVESTMENT SUMMARY Freehold. Located in the thriving South Bank district adjacent to Borough Market. London Bridge station is within a five minute walk from the property. Currently under refurbishment by Kaplan, the property comprises 45,012 sq ft (4,182 sq m) of accommodation arranged over ground and five upper floors. The accommodation includes 43,083 sq ft (4,002 sq m) of office and ancillary accommodation and a retail unit at part-ground and part-first floor extending to 1,929 sq ft (179 sq m). The office space is single let to Kaplan Estates Limited guaranteed by Kaplan UK Limited, a 5A1 rated company, for a term of 15 years expiring 31st August 2032, with a tenant option to determine on 31st August 2027. The overall passing rent of the office accommodation is £2,453,165.50 per annum (£57.76 per sq ft). The retail unit is let to Nero Holdings Limited t/a Caffè Nero for a term of 15 years from 11th June 2007 expiring 10th June 2022. The rent payable is subject to a minimum base rent of £150,000 per annum and an additional turnover rent (if applicable). -

The Politics of Architecture in Tudor and Stuart London Transcript

The Politics of Architecture in Tudor and Stuart London Transcript Date: Thursday, 11 February 2010 - 12:00AM Location: Museum of London The Politics of Architecture in Tudor and Stuart London Professor Simon Thurley Visiting Gresham Professor of the Built Environment 11/12/2010 Tonight, and again on the 11 March, I will be looking at the interrelation of architecture and power. The power of kings and the power of government and how that power has affected London. On the 11th I will be looking at Victorian and Edwardian London but tonight I'm going to concentrate on the sixteenth and seventeenth century and show how Tudor and Stuart Monarchs used, with varying degrees of success, the great buildings of the City of London to bolster their power. The story of royal buildings in the City starts with the Saxons. Before 1052 English Kings had had a palace in London at Aldermanbury, but principally to avoid the instability, turbulence and violence of the populace Edward the Confessor, the penultimate English King, had moved his royal palace one and a half miles west to an Island called Thorney. On Thorney Island the Confessor built the great royal abbey and palace of Westminster. And it was here, that William the Conqueror chose to be crowned on Christmas day 1066, safely away from the still hostile inhabitants of the city. London was too big, powerful and independent to be much influenced by the Norman Conquest. Business continued unabated under a deal done between the city rulers and their new king. However William left a major legacy by establishing the metropolitan geography of the English monarchy - the subject of my talk this evening. -

BANKSIDE, BOROUGH & LONDON BRIDGE Characterisation STUDY

APPENDIX 8 BANKSIDE, BOROUGH & LONDON BRIDGE CHARACTERISATION STUDY JULY 2013 Bankside, Borough and London Bridge Characterisation Study page 2 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 6 2. StrategiC CONTEXT 10 3. TOWNSCAPE CHARACTER AREAS 22 3.1 BLACKFRIARS ROAD NORTH 23 3.2 BLACKFRIARS ROAD SOUTH 33 Limitations 3.3 BANKSIDE CULTURAL 43 URS Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited (“URS”) has prepared this Report for the sole use of Southwark Council (“Client”) in accordance with the 3.4 BANKSIDE COMMERCIAL 53 Agreement under which our services were performed [3117681. 19 October 2012]. No other warranty, expressed or implied, is made as to the professional advice included in this Report or any other services provided by URS. This 3.5 BOROUGH MARKET 61 Report is confidential and may not be disclosed by the Client nor relied upon by any other party without the prior and express written agreement of URS. 3.6 THE BOROUGH 70 The conclusions and recommendations contained in this Report are based upon information provided by others and upon the assumption that all relevant information has been provided by those parties from whom it has 3.7 BOROUGH HIGH STREET 79 been requested and that such information is accurate. Information obtained by URS has not been independently verified by URS, unless otherwise stated 3.8 LONDON BRIDGE 89 in the Report. The methodology adopted and the sources of information used by URS in 3.9 BERMONDSEY 104 providing its services are outlined in this Report. The work described in this Report was undertaken between [insert date] and [insert date] and is based on the conditions encountered and the information available during the said REFERENCES 115 period of time. -

Redating Pericles: a Re-Examination of Shakespeare’S

REDATING PERICLES: A RE-EXAMINATION OF SHAKESPEARE’S PERICLES AS AN ELIZABETHAN PLAY A THESIS IN Theatre Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by Michelle Elaine Stelting University of Missouri Kansas City December 2015 © 2015 MICHELLE ELAINE STELTING ALL RIGHTS RESERVED REDATING PERICLES: A RE-EXAMINATION OF SHAKESPEARE’S PERICLES AS AN ELIZABETHAN PLAY Michelle Elaine Stelting, Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2015 ABSTRACT Pericles's apparent inferiority to Shakespeare’s mature works raises many questions for scholars. Was Shakespeare collaborating with an inferior playwright or playwrights? Did he allow so many corrupt printed versions of his works after 1604 out of indifference? Re-dating Pericles from the Jacobean to the Elizabethan era answers these questions and reveals previously unexamined connections between topical references in Pericles and events and personalities in the court of Elizabeth I: John Dee, Philip Sidney, Edward de Vere, and many others. The tournament impresas, alchemical symbolism of the story, and its lunar and astronomical imagery suggest Pericles was written long before 1608. Finally, Shakespeare’s focus on father-daughter relationships, and the importance of Marina, the daughter, as the heroine of the story, point to Pericles as written for a young girl. This thesis uses topical references, Shakespeare’s anachronisms, Shakespeare’s sources, stylometry and textual analysis, as well as Henslowe’s diary, the Stationers' Register, and other contemporary documentary evidence to determine whether there may have been versions of Pericles circulating before the accepted date of 1608. -

A HISTORY of LONDON in 100 PLACES

A HISTORY of LONDON in 100 PLACES DAVID LONG ONEWORLD A Oneworld Book First published in North America, Great Britain & Austalia by Oneworld Publications 2014 Copyright © David Long 2014 The moral right of David Long to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved Copyright under Berne Convention A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-78074-413-1 ISBN 978-1-78074-414-8 (eBook) Text designed and typeset by Tetragon Publishing Printed and bound by CPI Mackays, Croydon, UK Oneworld Publications 10 Bloomsbury Street London WC1B 3SR England CONTENTS Introduction xiii Chapter 1: Roman Londinium 1 1. London Wall City of London, EC3 2 2. First-century Wharf City of London, EC3 5 3. Roman Barge City of London, EC4 7 4. Temple of Mithras City of London, EC4 9 5. Amphitheatre City of London, EC2 11 6. Mosaic Pavement City of London, EC3 13 7. London’s Last Roman Citizen 14 Trafalgar Square, WC2 Chapter 2: Saxon Lundenwic 17 8. Saxon Arch City of London, EC3 18 9. Fish Trap Lambeth, SW8 20 10. Grim’s Dyke Harrow Weald, HA3 22 11. Burial Mounds Greenwich Park, SE10 23 12. Crucifixion Scene Stepney, E1 25 13. ‘Grave of a Princess’ Covent Garden, WC2 26 14. Queenhithe City of London, EC3 28 Chapter 3: Norman London 31 15. The White Tower Tower of London, EC3 32 16. Thomas à Becket’s Birthplace City of London, EC2 36 17. -

An Article in Southwark Magazine

Attractions Attractions powered Universal Testing Machine he built with the place. It’s astonishing that it’s still is preserved. here, and it’s so important that it survives. It’s This pioneering machine was historically a crucial part of the legacy of why buildings used for testing the suitability of building and bridges stand up, and underpins the materials for major infrastructure projects world’s standard of engineering established in that include Hammersmith Bridge and this building in Southwark Street.” Wembley Stadium. Museum trustee Sarah Jarvis says: “What OLD OPERATING THEATRE David was doing was very controversial at the When visitors head up the narrow 52-step time, as he was going against the way people staircase in the Old Operating Theatre, they were working. He was saying the only way to will be rewarded with a unique chance to ensure building and construction materials learn about the history of medicine. are safe is to test them rigorously and The oldest surviving surgical theatre in objectively, and to basically build on fact – Europe is tucked away next to the iconic not opinion.” Shard building, and is housed in the attic The volunteer-run museum opens on of the old St Thomas Hospital’s 18th the first Sunday and the third Wednesday of century church. every month, and regularly features as part of Sarah Corn is a year into her role as events such as Open House, London History director of this popular venue that opens Day and the Thames festival. seven days a week and annually has around Jarvis says Kirkaldy Testing Museum is 40,000 visitors. -

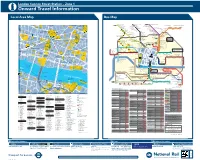

London Cannon Street Station – Zone 1 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

London Cannon Street Station – Zone 1 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map Palmers Green North Circular Road Friern Barnet Halliwick Park 149 S GRESHAM STREET 17 EDMONTON R 141 1111 Guildhall 32 Edmonton Green 65 Moorgate 12 A Liverpool Street St. Ethelburga’s Centre Wood Green I 43 Colney Hatch Lane Art Gallery R Dutch WALTHAMSTOW F for Reconcilation HACKNEY 10 Church E Upper Edmonton Angel Corner 16 N C A R E Y L A N E St. Lawrence 17 D I and Peace Muswell Hill Broadway Wood Green 33 R Mayor’s 3 T 55 ST. HELEN’S PLACE for Silver Street 4 A T K ING S ’S ARMS YARD Y Tower 42 Shopping City ANGEL COURT 15 T Jewry next WOOD Hackney Downs U Walthamstow E E & City 3 A S 6 A Highgate Bruce Grove RE 29 Guildhall U Amhurst Road Lea Bridge Central T of London O 1 E GUTTER LANE S H Turnpike Lane N St. Margaret G N D A Court Archway T 30 G E Tottenham Town Hall Hackney Central 6 R O L E S H GREEN TOTTENHAM E A M COLEMAN STREET K O S T 95 Lothbury 35 Clapton Leyton 48 R E R E E T O 26 123 S 36 for Whittington Hospital W E LOTHBURY R 42 T T 3 T T GREAT Seven Sisters Lea Bridge Baker’s Arms S T R E E St. Helen S S P ST. HELEN’S Mare Street Well Street O N G O T O T Harringay Green Lanes F L R D S M 28 60 5 O E 10 Roundabout I T H S T K 33 G M Bishopsgate 30 R E E T L R O E South Tottenham for London Fields I 17 H R O 17 Upper Holloway 44 T T T M 25 St. -

Cetacean Exploitation in Roman and Medieval London Van Den Hurk, Youri; Rielly, Kevin; Buckley, Mike

University of Groningen Cetacean exploitation in Roman and medieval London van den Hurk, Youri; Rielly, Kevin; Buckley, Mike Published in: Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports DOI: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.102795 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2021 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): van den Hurk, Y., Rielly, K., & Buckley, M. (2021). Cetacean exploitation in Roman and medieval London: Reconstructing whaling activities by applying zooarchaeological, historical, and biomolecular analysis. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 36, [102795]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.102795 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. -

Dr. Simon Thurley: General Bibliography

Dr. Simon Thurley: General Bibliography 1. Books Henry VIII, Images of a Tudor King, (Oxford, 1990, reprinted 1995 with corrections) (With Christopher Lloyd). The Royal Palaces of Tudor England: A Social and Architectural History, (Yale University Press, 1993). The King’s Privy Garden at Hampton Court Palace, 1689-1995, Ed., (Apollo, 1995). The Lost Palace of Whitehall, (Royal Institute of British Architects, Exhibition Catalogue, 1998, reprinted 1999). The Whitehall Palace Plan of 1670, (London Topographical Society Publication, 153, 1998). Whitehall Palace, an Architectural History of the Royal Apartments 1260-1698, (Yale University Press, 1999). Hampton Court Palace: A Social and Architectural History, (Yale, 2004 ). Lost Buildings of Britain (London, 1994) Somerset House (London Topographical Society Publication, 2006, in Preparation) Sir Christopher Wren and the Stuart Court (In preparation) 2. Articles in Academic Journals ‘Henry VIII and the Building of Hampton Court: A Reconstruction of the Tudor Palace’, Architectural History, 31, (1998), pp.1-57. ‘Excavations on the West Side of Whitehall 1960-2 Part I: From the Building of the Tudor Palace to the Construction of the Modern Offices of State’, The London and Middlesex Archaeological Society Transactions, (1990), pp.59-130. ‘The Tudor Kitchens at Hampton Court’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association, CXLIII, (1990), pp.1-28. ‘Whitehall Palace and King Street, Westminster: The Urban Cost of Princley Magnificence’, London Topographical Record, XXVI, (1990), pp.57-77, (with Gervaise Rosser). ‘The Building of the King’s Apartments, A most Popular Monarch’, Apollo, CXL, (1994), No. 390, pp. 10- 21. ‘William III’s Privy Garden at Hampton Court Palace: Research and Restoration’, Apollo , (June, 1995), pp.3-22. -

The Anchor Public House, Bankside, London Borough of Southwark

The Anchor Public House, Bankside, London Borough of Southwark An Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment for The Spirit Group by Steve Preston Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd Site Code ABS07/86 July 2007 Summary Site name: The Anchor Public House, Bankside, London Borough of Southwark Grid reference: TQ3244 8040 Site activity: Desk-based assessment Project manager: Steve Ford Site supervisor: Steve Preston Site code: ABS07/86 Area of site: c. 850 sq m Summary of results: The site is in an area of considerable archaeological potential and is occupied by a listed building. Previous evaluation trenching on the site exposed elements of 17th-century building (made ground layers, a cobbled surface and a cess pit) and later (18th- to 20th-century) works interpreted as possibly part of a waterworks, but nothing from any earlier period. This report may be copied for bona fide research or planning purposes without the explicit permission of the copyright holder Report edited/checked by: Steve Ford9 31.07.07 Jennifer Lowe9 02.08.07 i Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd, 47–49 De Beauvoir Road, Reading RG1 5NR Tel. (0118) 926 0552; Fax (0118) 926 0553; email [email protected]; website : www.tvas.co.uk The Anchor Public House, Bankside, London Borough of Southwark An Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment by Steve Preston Report 07/86 Introduction This desk-based study is an assessment of the archaeological potential of approximately 850 sq m of land located on Bankside in Southwark (TQ 3244 8040) (Fig. 1). The project was commissioned by Mr Mark Thackeray of Cliff Walsingham and Company, Bourne House, Cores End Road, Bourne End, Buckinghamshire SL8 5AR on behalf of The Spirit Group, and comprises the first stage of a process to determine the presence/absence, extent, character, quality and date of any archaeological remains which may be affected by redevelopment of the area. -

River Explorers' Trail

THE LONDON CURRICULUM RIVER EXPLORERs’ tRAIL 1 LONDON CURRICULUM RIVER EXPLORERs’ TRAIL NAME THE LONDON CURRICULUM RIVER EXPLORERs’ tRAIL 3 ABOUT THE LONDON CURRICULUM The London Curriculum supports the new national curriculum for students aged i 11–14. It uses the people, places and history of London to bring the curriculum to Did you know? life both inside and outside the classroom. It also encourages young Londoners to explore their cultural heritage. The word ‘Thames’ comes from the The River Explorers’ Trail has been designed to link to the London Curriculum. It can be names the native enjoyed by families, youth groups and anyone who wants to find out more about one of Britons gave to the the oldest and most fascinating cities in the world. river: Tamesis or Tamesa. You can find out more at london.gov.uk/curriculum On this trail you’ll learn why the River Thames has been vital to London’s development, and to Londoners, since the city was founded. You’ll find out more about some familiar river landmarks and a few lesser known ones. You’ll also discover how the Thames has inspired generations of artists, writers and poets. This booklet contains four different trails. Today, you’re following the: (circle as appropriate) THE LONDON CURRICULUM RIVER EXPLORERs’ tRAIL 4 KEY to SYMBOLS USED IN TRAIL: FIND WRITE DRAW OBSERVE IMAGINE DISCUSS THE LONDON CURRICULUM RIVER EXPLORERs’ tRAIL 5 StoPPING POINT: TOWER HILL You are standing near the eastern In Heart of Darkness Joseph Conrad Complete for trails: boundary of the City of London, imagines how the London area must have London’s central business district. -

Borough and Bankside Walking Route

The Statistics Sustainability and You This walk aims to encourage a ‘sustainable lifestyle’ by recognising the connection between Sustainability and 4000 Health and Well-being. The health benefits from walking are regularly emphasised by the NHS, who recommend This walk should The approximate The walk is taking an average of 10,000 steps a day to reduce the risk take around step count is 4000 approximately of type 2 diabetes, various cancers and heart disease. 45 – 50 minutes steps – around half 2 miles (3.3km). to complete at a of the recommended Additionally, the walks are a chance to improve mental moderate pace. amount for an wellbeing. If your job involves sitting in an indoor entire day. environment all day, it is important to get outside, move around and mentally refresh yourself. However, being in a densely populated, and at times, heavily polluted area Have the Time to Stop? like Central London means that sustainable living can be a difficult goal. This is why we have included various open If you have the opportunity to stop along your way, you could always pick up a bite to eat on campus or you might wish to green spaces to visit and enjoy. Not only are these spaces revisit the route after work in order to eat at a local business. rich in biodiversity and provide some tranquillity and cleaner If so, then here are some of our favourites! air, but they also offer a connection to the past and present local community. Burnt Lemon Bakery Flat Iron Square, 64 Union Street Located within a new mini-Borough Market complex, Burnt Safety Lemon focuses on sourdough breads made with organic flours with the source and seasonality of the ingredients paramount.