Title アイヌ音楽音組織の研究 Author(S)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kamuy Symphonia Holidays Summer Only

園内プログラム _ 表 英語 Screening of Short Films in the Hall t Entertainm kamuy yukar gh en Ni t As the sun sets, the presence of Short animations of tales handed down the generations kamuy (spirit-deities) grows. Dark & light, of Ainu. Images are projected not just on the screen, mysterious hues, an unforgettable experience. but on the floor as well, enveloping you in the story for Enjoy a Magical Night with kamuy. a 3D video experience. Outdoor Projection Mapping Show kamuy symphonia Holidays Summer Only This is the tale of the beginning of the world, as told by a fireside long ago by an old Ainu man. A light and sound show of the Ainu creation myths. Projection mapping makes the evening sparkle with visions of animals, trees and a lake -- an experience embracing the mythical world. Dome Screening Experience STORY The First kamuy eyes PROGRAM The Solar PROGRAM Kamuy Deity and What is displayed on the domed screen is a wondrous 2020.7.21-2020.8.30 the 2020.7.21-2020.8.30 The Owl’ s Lunar Into the Deity world that fuses fantasy and the nature of Hokkaido. One kamuy was born Tale Ainu Beginning of World It is the start of a thrilling adventure that unfolds from Sky and out of the orange vapor and Of these, There alighted a the perspective of the kamuy. Earth another from the pure sky the solar deity Finally, the two kamuy shimmering, and onto the earth. and the Long, long ago nothing yet lunar deity created humans rainbow-colored . -

The Goddess of the Wind and Okikurmi 萱野茂 風の神とオキク ルミ

Volume 9 | Issue 43 | Number 2 | Article ID 3621 | Oct 26, 2011 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus The Goddess of the Wind and Okikurmi 萱野茂 風の神とオキク ルミ Kyoko Selden, Kayano Shigeru The Goddess of the Wind andcontemporary artistic elements. Okikurmi1 The three major genres of Ainu oral tradition were kamuy yukar, songs of gods and By Kayano Shigeru demigods, yukar, songs of heroes, and Translated and Introduced by Kyoko wepeker, prose, or poetic prose, tales. The Ainu Selden linguist Chiri Mashiho (1909-1961) saw the origin of Ainu oral arts in the earliestkamuy Kayano Shigeru (1926-2006) was an inheritor yukar songs of gods, in which a shamanic and preserver of Ainu culture. As collector of performer imitated the voices and gestures of Ainu folk utensils, teacher of the prominent gods. In Ainu culture, everything had a divine Japanese linguist Kindaichi Kyōsuke, and spirit: owl, bear, fox, salmon, rabbit, insect, recorder and transcriber of epics, songs, and tree, rock, fire, water, wind, and so forth, some tales from the last of the bards. He was also a not so esteemed or even regarded downright fierce fighter against the construction of a dam wicked, and others revered as particularly in his village that meant destruction of a sacred divine. This gestured mimicry apparently ritual site as well as of nature. In addition, developed into kamuy yukar songs of gods, or Kayano was the compiler of an authoritative enacting of songs sung by gods, in which a Ainu-Japanese dictionary, a chanter of old human chanter impersonates a deity.Kamuy epics, the founder of a museum of Ainu yukar later included songs of Okikurmi-kamuy material culture as well as of an Ainu language (also called Kotan-kar-kamuy), a half god, half school and a radio station. -

Essay Title: Golden Kamuy: Can This Popular Manga Contribute To

ISSN: 1500-0713 ______________________________________________________________ Essay Title: Golden Kamuy: Can This Popular Manga Contribute to Ainu Studies? Author(s): Kinko Ito Source: Japanese Studies Review, Vol. XXIII (2019), pp. 155-168 Stable URL: https://asian.fiu.edu/projects-and-grants/japan- studiesreview/journal-archive/volume-xxiii-2019/ito-kinko-golden- kamuy.pdf ______________________________________________________________ GOLDEN KAMUY: CAN THIS POPULAR MANGA CONTRIBUTE TO AINU STUDIES? Kinko Ito University of Arkansas at Little Rock Introduction Golden Kamuy1 is an incredibly popular Japanese manga that has been serialized in Shūkan Young Jump, a weekly comic magazine, since August 21, 2014. The magazine is produced by Shueisha that publishes its komikkusu2 and digital media in Tokyo. The action adventure comic story by Satoru Noda revolves around two protagonists, Saichi Sugimoto, a returning Japanese soldier, and Asirpa, a beautiful Ainu girl in her teens. The manga also features many characters who play the roles of significant “supporting actors” for the dynamic development of the story. They all have strong and unique personalities, various criminal and non-criminal backgrounds, as well as complicated psychological characteristics. The compelling story also entails hunting, conflict, violence, food, and events in the history of Hokkaido, Japan and the world. Golden Kamuy has been creating much interest in the Ainu people, their history, and their culture among the Wajin (non-Ainu Japanese) in today’s Japan.3 I have been doing research on Japanese manga since the end of the 1980s and started my fieldwork on the Ainu during my sabbatical in the spring of 2011. In this essay, I am doing a content analysis of Golden Kamuy, paying special attention to the depiction of the Ainu and their culture as well as its educational values and contribution to the Ainu Studies. -

PORO OYNA: the Myth of the Aynu

SHADOWLIGHT PRODUCTIONS PRESENTS PORO OYNA: The Myth of the Aynu Thursday, January 16, 2014 School Matinee Performance Guide Prior to the About the Performance Performance PORO OYNA: The Myth of the Aynu is a new multidisciplinary shadow theatre work bringing the mythology of the Aynu (also Resources to share with your class commonly spelled as “Ainu”) tribe of Hokkaido, Japan, to life on & learn more about the Aynu stage, illuminating the power of this little known indigenous culture history, traditions, language, from the past and present. The show was created by shadow master clothing, present-day culture and Larry Reed in collaboration with musician OKI, a leading torchbearer featured artists prior to the performance. of the Aynu culture; and Tetsuro Koyano, a shadow theatre artist in Tokyo. The project will tell the legend of Ainu Rakkur, the beloved ShadowLight Productions Project demi-god, who rescues the Sun Goddess from the evil Monster, website: restoring the order in the land of humans. Other collaborators http://www.shadowlightaynuproject.org include: MAREWREW, a 4-woman chorus group specializing The Foundation for Research & traditional Aynu songs and members of Urotsutenoyako Promotion of Ainu Culture website: Bayangans, a shadow theatre company based in Tokyo. Through http://www.frpac.or.jp/english/together. this performance you will experience the centuries-old sacred world html of the Aynus and the complexity of Japanese cultural/social tapestry. The Ainu Association of Hokkaido http://www.ainu- Public Performance Schedule assn.or.jp/english/eabout01.html Jan 15 – 7:30pm Performance (Preview) Jan 16 – 7:30pm Performance (Opening Reception) Jan 17 – 7pm Panel Discussion / 8pm Performance Jan 18 – 2pm & 8pm Performance Jan 19 – 2pm Performance (Fort Mason Farmers Market activities) Tickets Available: http://www.brownpapertickets.com/event/520698 Aynu Culture The Ainu people regard things useful to them or beyond their control as "kamuy" (gods). -

Charanke and Hip Hop: the Argument for Re-Storying the Education of Ainu in Diaspora Through Performance Ethnography

CHARANKE AND HIP HOP: THE ARGUMENT FOR RE-STORYING THE EDUCATION OF AINU IN DIASPORA THROUGH PERFORMANCE ETHNOGRAPHY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION IN PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE JULY 2020 BY Ronda Shizuko Hayashi-Simpliciano Dissertation Committee Jamie Simpson Steele, Chairperson Amanda Smith Sachi Edwards Mary Therese Perez Hattori ii ABSTRACT The Ainu are recognized as an Indigenous people across the areas of Japan known as Hokkaido and Honshu, as well as the areas of Russia called Sakhalin, Kurile, and Kamchatka. In this research, the term Ainu in Diaspora refers to the distinct cultural identity of Ainu transnationals who share Ainu heritage and cultural identity, despite being generationally removed from their ancestral homeland. The distinct cultural identity of Ainu in Diaspora is often compromised within Japanese transnational communities due to a long history of Ainu being dehumanized and forcibly assimilated into the Japanese population through formalized systems of schooling. The purpose of this study is to tell the stories and lived experiences of five Ainu in Diaspora with autobiographic accounts as told by a researcher who is also a member of this community. In this study, the researcher uses a distinctly Ainu in Diaspora theoretical lens to describe the phenomena of knowledge-sharing between Indigenous communities who enter into mutually beneficial relationships to sustain cultural and spiritual identity. Cultural identity is often knowledge transferred outside of formal educational settings by the Knowledge Keepers through storytelling, art, and music. In keeping true to transformative research approaches, the Moshiri model normalizes the shamanic nature of the Ainu in Diaspora worldview as a methodological frame through the process of narrative inquiry. -

Lights of Okhotsk: a Partial Translation and Discussion in Regard to the Ainu/Enchiw of Karafuto

Lights of Okhotsk: A Partial Translation and Discussion in Regard to the Ainu/Enchiw of Karafuto Zea Rose Department of Global, Cultural and Language Studies The University of Canterbury Supervisor: Susan Bouterey A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Japanese, University of Canterbury, 2019. 1 Abstract This thesis aims to introduce the autobiography Lights of Okhotsk (2015) to a wider English- speaking audience by translating excerpts from the original Japanese into English. The author of Lights of Okhotsk, Abe Yoko, is Ainu and was born in Karafuto (the southern half of what is now known as Sakhalin) in 1933. Abe wrote about her life and experiences growing up in Karafuto before and during the Second World War as a minority. Abe also wrote of her life in Hokkaido following the end of the war and the forced relocation of Ainu away from Karafuto. Historical events such as the Second World War, 1945 invasion of Karafuto, along with language loss, traditional ecological knowledge, discrimination, and displacement are all themes depicted in the excerpts translated in this thesis. These excerpts also depict the everyday life of Abe’s family in Karafuto and their struggles in postwar Hokkaido. 2 Table of Contents Abstract .................................................................................................................................... 2 Table of Contents .................................................................................................................... -

Anime/Games/J-Pop/J-Rock/Vocaloid

Anime/Games/J-Pop/J-Rock/Vocaloid Deutsch Alice Im Wunderland Opening Anne mit den roten Haaren Opening Attack On Titans So Ist Es Immer Beyblade Opening Biene Maja Opening Catpain Harlock Opening Card Captor Sakura Ending Chibi Maruko-Chan Opening Cutie Honey Opening Detektiv Conan OP 7 - Die Zeit steht still Detektiv Conan OP 8 - Ich Kann Nichts Dagegen Tun Detektiv Conan Opening 1 - 100 Jahre Geh'n Vorbei Detektiv Conan Opening 2 - Laufe Durch Die Zeit Detektiv Conan Opening 3 - Mit Aller Kraft Detektiv Conan Opening 4 - Mein Geheimnis Detektiv Conan Opening 5 - Die Liebe Kann Nicht Warten Die Tollen Fussball-Stars (Tsubasa) Opening Digimon Adventure Opening - Leb' Deinen Traum Digimon Adventure Opening - Leb' Deinen Traum (Instrumental) Digimon Adventure Wir Werden Siegen (Instrumental) Digimon Adventure 02 Opening - Ich Werde Da Sein Digimon Adventure 02 Opening - Ich Werde Da Sein (Insttrumental) Digimon Frontier Die Hyper Spirit Digitation (Instrumental) Digimon Frontier Opening - Wenn das Feuer In Dir Brennt Digimon Frontier Opening - Wenn das Feuer In Dir Brennt (Instrumental) (Lange Version) Digimon Frontier Wenn Du Willst (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Eine Vision (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Ending - Neuer Morgen Digimon Tamers Neuer Morgen (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Opening - Der Grösste Träumer Digimon Tamers Opening - Der Grösste Träumer (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Regenbogen Digimon Tamers Regenbogen (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Sei Frei (Instrumental) Digimon Tamers Spiel Dein Spiel (Instrumental) DoReMi Ending Doremi -

The Goddess of the Wind and Okikurmi

Volume 14 | Issue 15 | Number 6 | Article ID 4932 | Aug 01, 2016 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus The Goddess of the Wind and Okikurmi Kayano Shigeru Translated and introduced by Kyoko Selden movement includes youthful attempts to create new forms that combine traditional Ainu oral performances with contemporary music and dance. Ainu Rebels, a creative song and dance troupe that formed in 2006, for example, is constituted mostly of Ainu youth but also includes Japanese and foreigners. The group draws on Ainu oral tradition adapted to hip hop and other forms and also engages in artistic activities that combine traditional Ainu art with contemporary artistic elements. Ainu Rebels 2009 performance with German subtitles Kayano Shigeru with Linguist Kindaichi Kyōsuke The three major genres of Ainu oral tradition were kamuy yukar (songs of gods and demigods), yukar (songs of heroes), and Kayano Shigeru (1926-2006) was an inheritor uepeker (prose, or poetic prose, tales). The and preserver of Ainu culture. He was a Ainu linguist Chiri Mashiho (1909-61, brother collector of Ainu folk utensils, teacher of the to Chiri Yukie whose work is included in this prominent Japanese linguist Kindaichi Kyōsuke, issue) located the origin of Ainu oral arts in the and recorder and transcriber of epics, songs, earliest kamuy yukar, in which a shamanic and tales from the last of the bards. In addition, performer imitated the voices and behavior of Kayano was the compiler of an authoritative the gods. In Ainu culture, everything had a Ainu-Japanese dictionary, a chanter of old divine spirit: owl, bear, fox, salmon, rabbit, epics, and the founder of a museum of Ainu insect, tree, rock, fire, water, wind, and so material culture as well as of an Ainu language forth. -

Role of the Sword Futsunomitama-No-Tsurugi in the Origin of the Japanese Bushidō Tradition

DOI: 10.4312/as.2018.6.2.211-227 211 Role of the Sword Futsunomitama-no-tsurugi in the Origin of the Japanese Bushidō Tradition G. Björn CHRISTIANSON, Mikko VILENIUS, Humitake SEKI*17 Abstract One of the formative narratives in Japanese martial arts is the bestowal of the mystical sword Futsunomitama-no-tsurugi upon Emperor Jinmu, the legendary founder of Japan. Within the Kashima Shinden Bujutsu lineage, this bestowal is attested as a critical event in the initiation of the principles of bushidō martiality. However, the practical reasons for its signicance have been unclear. Drawing on historical and archaeological records, in this paper we hypothesise that the physical conformation of the legendary sword Fut- sunomitama-no-tsurugi represented a comparatively incremental progression from the one-handed short swords imported from mainland Asia. ese modications allowed for a new, two-handed style of swordsmanship, and therefore it was the combination of the physical conformation of Futsunomitama-no-tsurugi and the development of appropriate techniques for wielding it that formed the basis of the martial signicance of the “Law of Futsu-no-mitama”. We also argue that this new tradition of swordsmanship was the nu- cleus around which the Kashima Shinden Bujutsu lineage would develop, and therefore represented a critical rst step towards the later concepts of bushidō. We also present a working model of what the techniques for usage of Futsunomitama-no-tsurugi might have been, and provide an account of an experiment testing its application. Keywords: bushidō, Kashima Shinden Bujutsu, Japan, archaeology, sword Vloga meča Futsunomitama-no-tsurugi na začetku japonske tradicije bushidōja Izvleček Ena od temeljnih pripovedi v kontekstu japonskih borilnih veščin je podelitev mistične- ga meča Futsunomitama-no-tsurugi cesarju Jinmuju, legendarnemu ustanovitelju Japon- ske. -

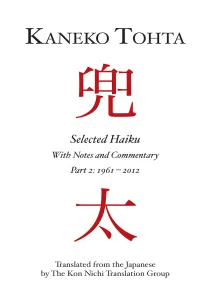

Selected Haiku

KANEKO TOHTA Selected Haiku With Notes and Commentary – Part 2 – 1961 – 2012 Translated by The Kon Nichi Translation Group Richard Gilbert ¤ Masahiro Hori Itō Yūki ¤ David Ostman ¤ Koun Franz Tracy Franz ¤ Kanamitsu Takeyoshi Kumamoto University 1 Kaneko Tohta: Selected Haiku With Notes and Commentary Part 2, 1961-2012 Copyright © 2012 ISBN 978-1-936848-21-8 Red Moon Press PO Box 2461 Winchester VA 22604-1661 USA www.redmoonpress.com Research supported by: The Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Research Grant-in-Aid, and Japan Ministry of Education (MEXT) Kakenhi 21520579. rmp o 2 Table of Contents Introduction to the Series . 5 Kaneko Tohta ¤ Selected Haiku 1. Toward Settled Wandering, 1961 – 1973 . 21 2. A “Settled Wanderer” of the Earth: Layers of History, 1974 – 1982 . 39 3. The Blessed: A Noted Poet Seeks Ancient Blessing Songs, 1983 – 1993 . 55 4. A Poet of Ikimonofūei, 1994 – 2012 . 71 Kaneko Tohta ¤ Notes to the Haiku 1. Toward Settled Wandering . 91 2. A “Settled Wanderer” of the Earth: Layers of History . 113 3. The Blessed: A Noted Poet Seeks Ancient Blessing Songs . 123 4. A Poet of Ikimonofūei . 139 3 Kaneko Tohta ¤ Indices Annotated Chronology . 153 Glossary of Terms . 197 Haiku Indices 1. First Line Index . 229 2. Alphabetical Index . 235 Translator Biographies . 243 4 Introduction to the Series KANEKO TOHTA (金子兜太, b. 1919) is among the most important literary and cultural innovators of postwar Japan. His career, the inception of which begins with his first haiku published at the age of 18, has now spanned 75 years, during which time he has pioneered major postwar modern-haiku movements, and become a leading literary and cultural figure as critic, teacher, scholar, and poet. -

The Ainu and Their Culture: a Critical Twenty-First Century Assessment

Volume 5 | Issue 11 | Article ID 2589 | Nov 03, 2007 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus The Ainu and Their Culture: A Critical Twenty-First Century Assessment Chisato (Kitty) Dubreuil The Ainu and Their Culture: A Critical Twenty-First Century Assessment Chisato ("Kitty") O. Dubreuil Chisato (“Kitty”) Dubreuil, an Ainu-Japanese art history comparativist, has charted connections between the arts of the Ainu and those of diverse indigenous peoples of the north Pacific Rim. Currently finishing her PhD dissertation, Dubreuil co-curated, with William Fitzhugh, the director of the Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center, the groundbreaking 1999 Smithsonian exhibition on Ainu culture. Insisting on the inclusion of the work of contemporary Ainu artists, as well as art and artifacts of past Ainu culture, her input redefined the scope of the exhibition and reflected her ongoing activism to challenge the “vanishing people” myth about the Ainu. Dubreuil explains, “We are still here and our culture is still vibrant.” Fig. 1: This is the most comprehensive, Dubreuil, with Fitzhugh, co-edited Ainu: Spirit interdisciplinary book ever published on the of a Northern People, published by the Ainu in English or Japanese. It has 415 pages Smithsonian in 1999, a critically acclaimed and over 500 illustrations. volume of interdisciplinary contributions by scholars of Ainu issues.Library Journal Her second award-winning book,From the described the volume as “the most in-depth Playground of the Gods: The Life and Art treatise available on Ainu prehistory, material -

Familiar and Unfamiliar Names of Mount Fuji1

Familiar and unfamiliar names of Mount Fuji1 Tomasz Majtczak Krakótu Kikishi yori mo | Omoishi yori mo | Mishi yori mo | Noborite takaki | Yama wa Fuji no ne. Kada no Azumamaro 荷 田 春 滿 (1669—1736) “The mountain which I found higher to climb than I had heard, than I had thought, than I had seen, - was Fuji's peak.” (Chamberlain 1905: 191) 1.In lurking (and from an etymological point of uieu)) The modern Standard Japanese name of the mountain in question is Fuji [$mn^i], written 富士,and it is usually provided with -san 山,the Sino-Japanese suffix for oronyms, i.e. Fuji-san [企mn也isaN] (exception ally also with -gan 巖 (= 巖 ),i.e. Fuji-gan, cf. Morohashi 1994: III, 3333). It goes back to an earlier form of Fuzi /$uzi/,Old Japanese Puzi /puzi/. Other names (like Fugaku) and related phrases (e.g. Fuji no yama) found in Japanese literature are now poetic or obsolete and will be dis cussed later on in this article. A river flowing southwards around the 1 This article was first presented in Polish (Znane i nieznane określenia góry Fudzi) on 21 March 2012 as a part of the lecture series “Fuji-san and Fuji yama. Narrations on Japan” (Fuji-san i Fuji-yama. Narracje o Japonii) or ganised by the Manggha Museum of Japanese Art and Technology and the Jagiellonian University's Department of Japanology and Sinology. It was also delivered in German (Bekannte und unbekannte Bezeichnungen des Berges Fuji) as a guest lecture at the Faculty of East Asian Studies, Ruhr- Universitat Bochum, on 9 July 2012.