She Shot Him Dead: the Criminalization of Women and the Struggle Over Social Order in Chicago, 1871-1919

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic & Business History

This article was published online on April 26, 2019 Final version June 30, 2019 Essays in ECONOMIC & BUSINESS HISTORY The Journal of the Economic &Business History Society Editors Mark Billings, University of Exeter Daniel Giedeman, Grand Valley State University Copyright © 2019, The Economic and Business History Society. This is an open access journal. Users are allowed to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of the articles in this journal without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISSN 0896-226X LCC 79-91616 HC12.E2 Statistics and London Underground Railways STATISTICS: SPUR TO PRODUCTIVITY OR PUBLICITY STUNT? LONDON UNDERGROUND RAILWAYS 1913-32 James Fowler The York Management School University of York [email protected] A rapid deterioration in British railways’ financial results around 1900 sparked an intense debate about how productivity might be improved. As a comparison it was noted that US railways were much more productive and employed far more detailed statistical accounting methods, though the connection between the two was disputed and the distinction between the managerial and regulatory role of US statistical collection was unexplored. Nevertheless, The Railway Companies (Accounts and Returns) Act was passed in 1911 and from 1913 a continuous, detailed and standardized set of data was produced by all rail companies including the London underground. However, this did not prevent their eventual amalgamation into the London Passenger Transport Board in 1933 on grounds of efficiency. This article finds that despite the hopes of the protagonists, collecting more detailed statistics did not improve productivity and suggests that their primary use was in generating publicity to influence shareholders’, passengers’ and workers’ perceptions. -

Hizzoner Big Bill Thompson : an Idyll of Chicago

2 LI E> HAHY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS B T478b cop. I . H . S . Hizzoner Big Bill Thompson JONATHAN CAPE AND HARRISON SMITH, INCORPORATED, 139 EAST 46TH STREET, NEW YORK, N. Y. AND 77 WELLINGTON STREET, WEST, TORONTO, CANADA; JONATHAN CAPE, LTD. 30 BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON, W. C. 1, ENGLAND Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://archive.org/details/hizzonerbigbilltOObrig ->-^ BIG BILL THOMPSON (CARICATURE BY CARRENO) BY JOHN BRIGHT Introduction by Harry Elmer Barnes Hizzoner Big Bill Thompson An Idyll of Chicago NEW YORK JONATHAN CAPE & HARRISON SMITH COPYRIGHT, 1930, BY JOHN BRIGHT FIRST PUBLISHED 1930 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY J. J. LITTLE & IVES CO. AND BOUND BY THE J. F. TAPLEY CO. — r TH i This Book Is Respectfully Dedicated to MR. WALTER LIPPMANN ". Here and there some have found a way of life in this new world. They have put away vain hopes, have ceased to ask guaranties and are yet serene. But they are only a handful. They do the enduring work of the world, for work like theirs, done with no ulterior bias and for its own sake, is work done in truth, in beauty, and in goodness. There is not much of it, and it does not greatly occupy the attention of mankind. Its excellence is quiet. But it persists through all the spectacular commotions. And long after, it is all that men care much to remember." American Inquisitors. BIG BILL THE BUILDER A Campaign Ditty Scanning his fry's pages, we find names we love so well, Heroes of the ages—of their deeds we love to tell, But right beside them soon there'll be a name Of someone we all acclaim. -

The Origins of Political Electricity: Market Failure Or Political Opportunism?

THE ORIGINS OF POLITICAL ELECTRICITY: MARKET FAILURE OR POLITICAL OPPORTUNISM? Robert L. Bradley, Jr. * The current debate over restructuring the electric industry, which includes such issues as displacing the regulatory covenant, repealing the Public Utility Holding Company Act, and privatizing municipal power sys- tems, the Rural Utilities Service (formerly Rural Electrification Adminis- tration), and federally owned power systems, makes a look back at the origins of political electricity relevant. The thesis of this essay, that govern- ment intervention into electric markets was not the result of market fail- ures but, rather, represented business and political opportunism, suggests that the intellectual and empirical case for market-oriented reform is even stronger than would otherwise be the case. A major theme of applied political economy is the dynamics of gov- ernment intervention in the marketplace. Because interventions are often related, an analytical distinction can be made between basis point and cumulative intervention.' Basis point regulation, taxation, or subsidization is the opening government intervention into a market setting; cumulative intervention is further regulation, taxation, or subsidization that is attribu- table to the effects of prior (basis point or cumulative) intervention. The origins and maturation of political electricity, as will be seen, are interpret- able through this theoretical framework. The commercialization of electric lighting in the United States, suc- cessfully competing against gas lamps, kerosene lamps, and wax candles, required affordable generation, long distance transmission capabilities, and satisfactory illumination equipment. All three converged beginning in the 1870s, the most remembered being Thomas Edison's invention of the incandescent electric light bulb in 1878. - * Robert L. -

Mental Health Professionals According to Prime-Time: an Exploratory Analysis

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 424 499 CG 028 776 AUTHOR Diefenbach, Donald L.; Burns, Naomi J.; Schwartz, Alan L. TITLE Mental Health Professionals According to Prime-Time: An Exploratory Analysis. PUB DATE 1998-08-00 NOTE 15p.; Paper presented at the American Psychological Association Annual Convention (106th, San Francisco, CA, August 14-18, 1998). PUB TYPE Reports Research (143)-- Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Broadcast Television; *Mass Media Effects; Media Research; Mental Health Workers; Television Research IDENTIFIERS *Prime Time Television ABSTRACT The public receives a large percentage of its information about mental health issues from media sources. Research has shown that the portrayal of occupational roles is often distorted and unrealistic. Cultivation theory predicts that television's version of reality helps influence or "cultivate" viewers' beliefs about the world. This cultivation might influence a person's expectations or behavior during an encounter with these professionals, or even influence viewers' decisions to consult these professionals when in need of service. Research for this paper employed mixed methods to explore how mental health professionals are portrayed on television. Analysis of characters involved a random sample across all genres of programming. Trained coders (n=9) identified 10 out of 1,844 speaking characters as mental health professionals. Descriptive statistics are reported on the characters. A content analysis by type of programming-is presented and discussed. Exploratory analysis examining the portrayal of mental health professionals on prime-time television indicates that portrayals can not be classified by tone in a single category; however tone appears to be consistent within certain programming genres. -

Mmacarthur Foundation. the John D

Alphabetic-L Encyclopedia of Chicago UC-Enc-v.cls May , : LYRIC OPERA Further reading: Andreas, A. T. History of Cook At Krainik’s death in January she was W W I, and after a long lull, resumed County Illinois. • Benedetti, Rose Marie. Village succeeded by William Mason, the company’s in the decades after W W II. In the first on the River, –. • Lyons Diamond Ju- director of operations, artistic and produc- stage, thousands of Macedonians left the Old bilee, –. tion. As the Lyric entered the early twenty-first Country in the wake of the bloody Ilin- century, it remained internationally respected den Uprising against Ottoman control, which Lyric Opera. From to ,seven as a theater of high performance standards rest- ended with the ruin of some villages and companies—several merely different ing on an enviably secure financial base. exposed many Macedonian men to conscrip- names for the same reorganized company— John von Rhein tion in the Ottoman army. The rest came as presented seasons at Chicago’sA male labor migrants who sought to improve See also: Classical Music; Entertaining Chicagoans T and the Civic Opera House. All their families’ grim economic fortunes by re- Further reading: Cassidy, Claudia. Lyric Opera of turning home with earnings from American sunk in a sea of debt. From to the Chicago. • Davis, R. Opera in Chicago. city had no resident opera company. Three factories. After World War I, with their home people changed everything: Carol Fox, a stu- country divided between Bulgaria, Serbia, and dent singer; Lawrence Kelly, a businessman; Greece, the thousands of Chicago-area Mace- and Nicola Rescigno, a conductor and vocal donians recognized that they would not re- teacher. -

Give Me Liberty!

CHAPTER 18 1889 Jane Addams founds Hull House 1898 Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Women and Economics 1900 Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie 1901 President McKinley assassinated Socialist Party founded in United States 1902 President Theodore Roosevelt assists in the coal strike 1903 Women’s Trade Union League founded 1904 Lincoln Steffen’s The Shame of the Cities Ida Tarbell’s History of the Standard Oil Company Northern Securities dissolved 1905 Ford Motor Company established Industrial Workers of the World established 1906 Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle Pure Food and Drug Act Meat Inspection Act Hepburn Act John A. Ryan’s A Living Wage 1908 Muller v. Oregon 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Company fire Society of American Indians founded 1912 Theodore Roosevelt organizes the Progressive Party Children’s Bureau established 1913 Sixteenth Amendment ratified Seventeenth Amendment ratified Federal Reserve established 1914 Clayton Act Ludlow Massacre Federal Trade Commission established Walter Lippmann’s Drift and Mastery 1915 Benjamin P. DeWitt’s The Progressive Movement The Progressive Era, 1900–1916 AN URBAN AGE AND A THE POLITICS OF CONSUMER SOCIETY PROGRESSIVISM Farms and Cities Effective Freedom The Muckrakers State and Local Reforms Immigration as a Global Progressive Democracy Process Government by Expert The Immigrant Quest for Jane Addams and Hull House Freedom “Spearheads for Reform” Consumer Freedom The Campaign for Woman The Working Woman Suffrage The Rise of Fordism Maternalist Reform The Promise of Abundance The Idea of Economic An American -

Lillie Enclave” Fulham

Draft London Plan Consultation: ref. Chapter 7 Heritage - Neglect & Destruction February 2018 The “Lillie Enclave” Fulham Within a quarter mile radius of Lillie Bridge, by West Brompton station is A microcosm of the Industrial Revolution - A part of London’s forgotten heritage The enclave runs from Lillie Bridge along Lillie Road to North End Road and includes Empress (formerly Richmond) Place to the north and Seagrave Road, SW6 to the south. The roads were named by the Fulham Board of Works in 1867 Between the Grade 1 Listed Brompton Cemetery in RBKC and its Conservation area in Earl’s Court and the Grade 2 Listed Hermitage Cottages in H&F lies an astonishing industrial and vernacular area of heritage that English Heritage deems ripe for obliteration. See for example, COIL: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1439963. (Former HQ of Piccadilly Line) The area has significantly contributed to: o Rail and motor Transport o Building crafts o Engineering o Rail, automotive and aero industries o Brewing and distilling o Art o Sport, Trade exhibitions and mass entertainment o Health services o Green corridor © Lillie Road Residents Association, February1 2018 Draft London Plan Consultation: ref. Chapter 7 Heritage - Neglect & Destruction February 2018 Stanford’s 1864 Library map: The Lillie Enclave is south and west of point “47” © Lillie Road Residents Association, February2 2018 Draft London Plan Consultation: ref. Chapter 7 Heritage - Neglect & Destruction February 2018 Movers and Shakers Here are some of the people and companies who left their mark on just three streets laid out by Sir John Lillie in the old County of Middlesex on the border of Fulham and Kensington parishes Samuel Foote (1722-1777), Cornishman dramatist, actor, theatre manager lived in ‘The Hermitage’. -

Copyright by Jeffrey Wayne Parker 2013

Copyright by Jeffrey Wayne Parker 2013 The Dissertation Committee for Jeffrey Wayne Parker Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Empire’s Angst: The Politics of Race, Migration, and Sex Work in Panama, 1903-1945 Committee: Frank A. Guridy, Supervisor Philippa Levine Minkah Makalani John Mckiernan-González Ann Twinam Empire’s Angst: The Politics of Race, Migration, and Sex Work in Panama, 1903-1945 by Jeffrey Wayne Parker, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2013 Dedication To Naoko, my love. Acknowledgements I have benefitted greatly from a wide ensemble of people who have made this dissertation possible. First, I am deeply grateful to my adviser, Frank Guridy, who over many years of graduate school consistently provided unwavering support, needed guidance, and inspiration. In addition to serving as a model historian and mentor, he also read countless drafts, provided thoughtful insights, and pushed me on key questions and concepts. I also owe a major debt of gratitude to another incredibly gifted mentor, Ann Twinam, for her stalwart support, careful editing, and advice throughout almost every stage of this project. Her diligent commitment to young scholars immeasurably improved my own writing abilities and professional development as a scholar. John Mckiernan-González was also an enthusiastic advocate of this project who always provided new insights into how to make it better. Philippa Levine and Minkah Makalani also carefully read the dissertation, provided constructive insights, edited chapters, and encouraged me to develop key aspects of the project. -

Come Into My Parlor. a Biography of the Aristocratic Everleigh Sisters of Chicago

COME INTO MY PARLOR Charles Washburn LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN IN MEMORY OF STEWART S. HOWE JOURNALISM CLASS OF 1928 STEWART S. HOWE FOUNDATION 176.5 W27c cop. 2 J.H.5. 4l/, oj> COME INTO MY PARLOR ^j* A BIOGRAPHY OF THE ARISTOCRATIC EVERLEIGH SISTERS OF CHICAGO By Charles Washburn Knickerbocker Publishing Co New York Copyright, 1934 NATIONAL LIBRARY PRESS PRINTED IN U.S.A. BY HUDSON OFFSET CO., INC.—N.Y.C. \a)21c~ contents Chapter Page Preface vii 1. The Upward Path . _ 11 II. The First Night 21 III. Papillons de la Nun 31 IV. Bath-House John and a First Ward Ball.... 43 V. The Sideshow 55 VI. The Big Top .... r 65 VII. The Prince and the Pauper 77 VIII. Murder in The Rue Dearborn 83 IX. Growing Pains 103 X. Those Nineties in Chicago 117 XL Big Jim Colosimo 133 XII. Tinsel and Glitter 145 XIII. Calumet 412 159 XIV. The "Perfessor" 167 XV. Night Press Rakes 173 XVI. From Bawd to Worse 181 XVII. The Forces Mobilize 187 XVIII. Handwriting on the Wall 193 XIX. The Last Night 201 XX. Wayman and the Final Raids 213 XXI. Exit Madams 241 Index 253 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My grateful appreciation to Lillian Roza, for checking dates John Kelley, for early Chicago history Ned Alvord, for data on brothels in general Tom Bourke Pauline Carson Palmer Wright Jack Lait The Chicago Public Library The New York Public Library and The Sisters Themselves TO JOHN CHAPMAN of The York Daily News WHO NEVER WAS IN ONE — PREFACE THE EVERLEIGH SISTERS, should the name lack a familiar ring, were definitely the most spectacular madams of the most spectacular bagnio which millionaires of the early- twentieth century supped and sported. -

A Rare Campaign for Senate Succession Senate President Pro Tem Sen

V23, N25 Tursday, Feb. 15, 2018 A rare campaign for Senate succession Senate President Pro Tem Sen. Ryan Mishler in Kenley’s appropria- Long’s announcement sets up tions chair, and Sen. Travis Holdman in battle last seen in 2006, 1980 Hershman’s tax and fscal policy chair. By BRIAN A. HOWEY Unlike former House INDIANAPOLIS – The timing of Senate minority leader Scott President Pro Tempore David Long’s retirement Pelath, who wouldn’t announcement, coming even vote on a suc- in the middle of this ses- cessor, Long is likely sion, was the big surprise to play a decisive on Tuesday. But those of role here. As one us who read Statehouse hallway veteran ob- tea leaves, the notion served, “I think Da- that Long would follow vid will play a large his wife, Melissa, into the sunset was a change and positive role in of the guard realization that began to take shape choosing his succes- with Long’s sine die speech last April. sor. That’s a good For just the third time since 1980, this thing in my view. sets up a succession dynamic that will be fasci- He is clear-eyed and nating. Here are several key points to consider: knows fully what is n Long is taking a systemic approach to Senate President Pro Tem David Long said Tuesday, required of anyone reshaping the Senate with the reality that after “No one is indispensible” and “you know when it’s in that role. And ... November, he, Luke Kenley and Brandt Hersh- time to step down. -

Prostitutes, Feminists, and the War on White Slavery

Decades of Reform: Prostitutes, Feminists, and the War on White Slavery By: Jodie Masotta Under the direction of: Professor Nicole Phelps & Professor Major Jackson University of Vermont Undergraduate Honors Thesis College of Arts and Sciences, Honors College Department of History & Department of English April 2013 Introduction to Project: This research should be approached as an interdisciplinary project that combines the fields of history and English. The essay portion should be read first and be seen as a way to situate the poems in a historical setting. It is not merely an extensive introduction, however, and the argument that it makes is relevant to the poetry that comes afterward. In the historical introduction, I focus on the importance of allowing the prostitutes that lived in this time to have their own voice and represent themselves honestly, instead of losing sight of their desires and preferences in the political arguments that were made at the time. The poetry thus focuses on providing a creative and representational voice for these women. Historical poetry straddles the disciplines of history and English and “through the supremacy of figurative language and sonic echoes, the [historical] poem… remains fiercely loyal to the past while offering a kind of social function in which poetry becomes a ritualistic act of remembrance and imagining that goes beyond mere narration of history.”1 The creative portion of the project is a series of dramatic monologues, written through the voices of prostitutes that I have come to appreciate and understand as being different and individualized through my historical research The characters in these poems should be viewed as real life examples of women who willingly became prostitutes. -

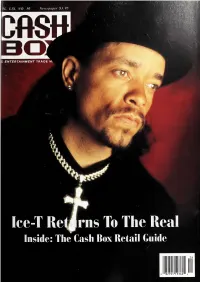

Ice-T Re^Rns to the Real Inside: the Cash Box Retail Guide

'f)L. LIX, NO. 30 Newspaper $3.95 ftSo E ENTERTAINMENT TRADE M. rj V;K Ice-T Re^rns To The Real Inside: The Cash Box Retail Guide 0 82791 19360 4 VOL. LIX, NO. 30 April 6, 1996 NUMBER ONES STAFF GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher POP SINGLE KEITH ALBERT THE ENTERTAINMENT TRADE MAGAZINE Exec. V.PJOeneral Manager Always Baby Be My M.R. MARTINEZ Mariah Carey Managing Editor (Columbia) EDITORIAL Los Angdes JOhM GOFF GIL ROBERTSON IV DAINA DARZIN URBAN SINGLE HECTOR RESENDEZ, Latin Edtor Cover Story Nashville Down Low ^AENDY NEWCOMER New York R. Kelly Ice-T Keeps It Real J.S GAER (Jive) CHART RESEARCH He’s established himself as a rapper to be reckoned with, and has encountered Los Angdes BRIAN PARMELLY his share of controversy along the way. But Ice-T doesn’t mind keepin’ it real, ZIV RAP SINGLE which is the key element in his new Rhyme Syndicate/ Priority release Ice VI: TONY RUIZ PETER FIRESTONE The Return Of The Real. The album is being launched into the consciousness of Woo-Hah! Got You... Retail Gude Research fans and foes with a wickedly vigorous marketing and media campaign that LAURI Busta Rhymes Nashville artist’s power. Angeles-based rapper talks with underscores the The Los Cash GAIL FRANCESCHl (Elektra) Box urban editor Gil Robertson IV about the record, his view of the industry MARKETINO/ADVERTISINO today and his varied creative ventures. Los A^gdes FRANK HIGGINBOTHAM —see page 5 JOI-TJ RHYS COUNTRY SINGLE BOB CASSELL Nashville To Be Loved By You The Cash Box Retail Guide Inside! TED RANDALL V\^nonna New York NOEL ALBERT (Curb) CIRCULATION NINATREGUB, Managa- Check Out Cash Box on The Internet at JANET YU PRODUCTION POP ALBUM HTTP: //CASHBOX.COM.