Advancing Women's Rights in Davao City, Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President Duterte's First Year in Office

ISSUE: 2017 No. 44 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore | 28 June 2017 Ignoring the Curve: President Duterte’s First Year in Office Malcolm Cook* EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte has adopted a personalised approach to the presidency modelled on his decades as mayor and head of a local political dynasty in Davao City. His political history, undiminished popularity and large Congressional majorities weigh heavily against any change being made in approach. In the first year of his presidential term this approach has contributed to legislative inertia and mixed and confused messages on key policies. Statements by the president and leaders in Congress questioning the authority of the Supreme Court in relation to martial law, and supporting constitutional revision put into question the future of the current Philippine political system. * Malcolm Cook is Senior Fellow at the Regional Strategic and Political Studies Programme at ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute. 1 ISSUE: 2017 No. 44 ISSN 2335-6677 INTRODUCTION After his clear and surprise victory in the 9 May 2016 election, many observers, both critical and sympathetic, argued that Rodrigo Duterte would face a steep learning curve when he took his seat in Malacañang (the presidential palace) on 30 June 2016.1 Being president of the Philippines is very different than being mayor of Davao City in southern Mindanao. Learning curve proponents argue that his success in mounting this curve from mayor and local political boss to president would be decisive for the success of his administration and its political legacy. A year into his single six-year term as president, it appears not only that President Duterte has not mounted this steep learning curve, he has rejected the purported need and benefits of doing so.2 While there may be powerful political reasons for this rejection, the impact on the Duterte administration and its likely legacy appears quite decisive. -

Duterte and Philippine Populism

JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY ASIA, 2017 VOL. 47, NO. 1, 142–153 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2016.1239751 COMMENTARY Flirting with Authoritarian Fantasies? Rodrigo Duterte and the New Terms of Philippine Populism Nicole Curato Centre for Deliberative Democracy & Global Governance, University of Canberra, Australia ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This commentary aims to take stock of the 2016 presidential Published online elections in the Philippines that led to the landslide victory of 18 October 2016 ’ the controversial Rodrigo Duterte. It argues that part of Duterte s KEYWORDS ff electoral success is hinged on his e ective deployment of the Populism; Philippines; populist style. Although populism is not new to the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte; elections; Duterte exhibits features of contemporary populism that are befit- democracy ting of an age of communicative abundance. This commentary contrasts Duterte’s political style with other presidential conten- ders, characterises his relationship with the electorate and con- cludes by mapping populism’s democratic and anti-democratic tendencies, which may define the quality of democratic practice in the Philippines in the next six years. The first six months of 2016 were critical moments for Philippine democracy. In February, the nation commemorated the 30th anniversary of the People Power Revolution – a series of peaceful mass demonstrations that ousted the dictator Ferdinand Marcos. President Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III – the son of the president who replaced the dictator – led the commemoration. He asked Filipinos to remember the atrocities of the authoritarian regime and the gains of democracy restored by his mother. He reminded the country of the torture, murder and disappearance of scores of activists whose families still await compensation from the Human Rights Victims’ Claims Board. -

NDRRMC Update Sitrep No. 48 Flooding & Landslides 21Jan2011

FB FINELY (Half-submerged off Diapila Island, El Nido, Palawan - 18 January 2011) MV LUCKY V (Listed off the Coast of Aparri, Cagayan - 18 Jan) The Pineapple – a 38-footer Catamaran Sailboat twin hulled (white hull and white sails) departed Guam from Marianas Yatch Club 6 January 2011 which is expected to arrive Cebu City on 16 January 2011 but reported missing up to this time Another flooding and landslide incidents occurred on January 16 to 18, 2011 in same regions like Regions IV-B, V, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI and ARMM due to recurrence of heavy rains: Region IV-B Thirteen (13) barangays were affected by flooding in Narra, Aborllan, Roxas and Puerto Princesa City, Palawan Region V Landslide occurred in Brgy. Calaguimit, Oas, Albay on January 20, 2011 with 5 houses affected and no casualty reported as per report of Mayor Gregorio Ricarte Region VII Brgys Poblacion II and III, Carcar, Cebu were affected by flooding with 50 families affected and one (1) missing identified as Sherwin Tejada in Poblacion II. Ewon Hydro Dam in Brgy. Ewon and the Hanopol Hydro Dam in Brgy. Hanopol all in Sevilla, Bohol released water. Brgys Bugang and Cambangay, Brgys. Napo and Camba in Alicia and Brgys. Canawa and Cambani in Candijay were heavily flooded Region VIII Brgys. Camang, Pinut-an, Esperanza, Bila-tan, Looc and Kinachawa in San Ricardo, Southern Leyte were declared isolated on January 18, 2011 due to landslide. Said areas werer already passable since 19 January 2011 Region IX Brgys San Jose Guso and Tugbungan, Zamboanga City were affected by flood due to heavy rains on January 18, 2011 Region X One protection dike in Looc, Catarman. -

Chapter 5 Improved Infrastructure and Logistics Support

Chapter 5 Improved Infrastructure and Logistics Support I. REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES Davao Region still needs to improve its infrastructure facilities and services. While the Davao International Airport has been recently completed, road infrastructure, seaport, and telecommunication facilities need to be upgraded. Flood control and similar structures are needed in flood prone areas while power and water supply facilities are still lacking in the region’s remote and underserved areas. While the region is pushing for increased production of staple crops, irrigation support facilities in major agricultural production areas are still inadequate. Off-site infrastructure in designated tourism and agri-industrial areas are likewise needed to encourage investment and spur economic activities. Accessibility and Mobility through Transport There is a need for the construction of new roads and improvement of the existing road network to provide better access and linkage within and outside the Region as an alternate to existing arterial and local roads. The lack of good roads in the interior parts of the municipalities and provinces connecting to major arterial roads constrains the growth of agriculture and industry in the Region; it also limits the operations of transport services due to high maintenance cost and longer turnaround time. Traffic congestion is likewise becoming a problem in highly urbanized and urbanizing areas like Davao City and Tagum City. While the Region is physically connected with the adjoining regions in Mindanao, poor road condition in some major highways also hampers inter-regional economic activities. The expansion of agricultural activities in the resettlement and key production areas necessitates the opening and construction of alternative routes and farm-to-market roads. -

A Biography of President Rodrigo Roa Duterte, by Earl G

Book Review Beyond Will and Power: A Biography of President Rodrigo Roa Duterte, by Earl G. Parreño. Lapu-lapu City: Optima Typographics, 2019. Pp. 227. ISBN 9786218161023. Cleve V. Arguelles For an enigmatic man like Philippine President Rodrigo Roa Duterte, to write an account of the man’s life is surely a demanding enterprise. Independent journalist Earl Parreño boldly took up the challenge and succeeded in constructing a comprehensive profile of the man. Through a laborious gathering of countless interviews and documents, the result is the book Beyond Will and Power, a short biography of Duterte focusing on his political and family life prior to his rise to Malacañang. While a cottage industry around Duterte has been booming among many writers since his presidential victory in 2016, many works produced have barely scratched the surface. This book is both a timely and necessary intervention: the details of his past lives, especially before his time as the infamous Davao City mayor, have yet to be made accessible. The emphasis on the rich political and family life trajectories of the Duterte clan, meaningfully situated in the sociohistorical development of Davao, Mindanao, and the nation, is the book’s most significant contributions. However, the book’s attempt to decouple Duterte from his destructive legacy to Philippine society is a weak point that cannot be easily overlooked. In this review, I will give a brief overview of the book, followed by a short discussion of what this biography can potentially offer for the study of Philippine politics and society, and ends with a critical reflection on the ethics of writing a political biography. -

The Influence of China on Philippine Foreign Policy: the Case of Duterte’S Independent Foreign Policy

THE INFLUENCE OF CHINA ON PHILIPPINE FOREIGN POLICY: THE CASE OF DUTERTE’S INDEPENDENT FOREIGN POLICY BY MR. NATHAN DANIEL V. SISON A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIA PACIFIC STUDIES COLLEGE OF INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES THAMMASAT UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC YEAR 2017 COPYRIGHT OF THAMMASAT UNIVERSITY Ref. code: 25605966090168XQU THE INFLUENCE OF CHINA ON PHILIPPINE FOREIGN POLICY: THE CASE OF DUTERTE’S INDEPENDENT FOREIGN POLICY BY MR. NATHAN DANIEL V. SISON A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIA PACIFIC STUDIES COLLEGE OF INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES THAMMASAT UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC YEAR 2017 COPYRIGHT OF THAMMASAT UNIVERSITY Ref. code: 25605966090168XQU (1) Thesis Title THE INFLUENCE OF CHINA ON PHILIPPINE FOREIGN POLICY: THE CASE OF DUTERTE‟S INDEPENDENT FOREIGN POLICY Author Mr. Nathan Daniel Velasquez Sison Degree Master of Arts in Asia-Pacific Studies Major Major Field/Faculty/University College of Interdisciplinary Studies Thammasat University Thesis Advisor Associate Professor Chanintira na Thalang, Ph.D. Academic Year 2017 ABSTRACT Since the start of his administration, President Rodrigo Roa Duterte has pursued a foreign policy which has been in contrast with the containment policy of the Aquino administration towards China. The new leader immediately pushed forward for a true practice of independent foreign policy which denotes that the country will seek closer relations with China and Russia as it distances itself from its traditional ally, the US. The policy shift of this administration is also understood as a “Pivot to China,” which explicitly demonstrate a change in the normal pattern of the country‟s strategic diplomacy with aims of diversifying options and improving relations with other countries. -

Katipunan- Kasilak to Farm Market Road in Panabo City

Rahabilitation of Brgy. Little Panay- Katipunan- Kasilak to Farm Market Road in Panabo City Panabo City, Davao del Norte April 2014 Initial Environmental Examination Report CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 PROJECT BACKGROUND The subproject covers the three barangays namely Barangays Little Panay, Katipunan and Kasilak. These three (3) barangays has attained a technical assistance grant from the Local Government unit of Panabo and Department of Agriculture through Mindanao Rural Development Program (MRDP), a poverty-reduction program for the rural poor, women and indigenous communities in mindanao which is funded largely through a World Bank loan. The proposed subproject has a full stretch of 8.002 Km. starting from Purok 3, Purok 5 of Barangay Little Panay passing Purok 4 to San Miguel of Barangay Katipunan and will end at Purok 3-B of Barangay Kasilak. The road influences the entire area of the subproject barangays that has a total of 2,382 hectares. Rehabilitation of the farm to market road from barangay Little Panay to purok 4 barangay Kasilak play a significant role in rural and agricultural development in such a way that will make the areas and its immediate environs into a more usable and will achieve its maximum potential in terms of agricultural production. Although not all residents utilized this road at present but with the rehabilitation of access, the constituents of the subproject barangays and its neighbors will benefit directly or indirectly with it. This will cause the alteration particularly of its increase in land valuation, increase revenues and farmers’ income at least 25% starting year 2013. -

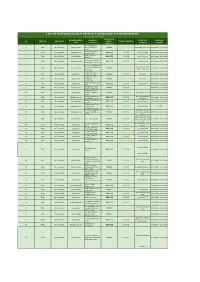

List of Licensed Covid-19 Testing Laboratory in the Philippines

LIST OF LICENSED COVID-19 TESTING LABORATORY IN THE PHILIPPINES ( as of November 26, 2020) OWNERSHIP MUNICIPALITY / NAME OF CONTACT LICENSE REGION PROVINCE (PUBLIC / TYPE OF TESTING # CITY FACILITY NUMBER VALIDITY PRIVATE) Amang Rodriguez 1 NCR Metro Manila Marikina City Memorial Medical PUBLIC Cartridge - Based PCR 8948-0595 / 8941-0342 07/18/2020 - 12/31/2020 Center Asian Hospital and 2 NCR Metro Manila Muntilupa City PRIVATE rRT PCR (02) 8771-9000 05/11/2020 - 12/31/2020 Medical Center Chinese General 3 NCR Metro Manila City of Manila PRIVATE rRT PCR (02) 8711-4141 04/15/2020 - 12/31/2020 Hospital Detoxicare Molecular 4 NCR Metro Manila Mandaluyong City PRIVATE rRT PCR (02) 8256-4681 04/11/2020 - 12/31/2020 Diagnostics Laboratory Dr. Jose N. Rodriguez Memorial Hospital and (02) 8294-2571; 8294- 5 NCR Metro Manila Caloocan City PUBLIC Cartridge - Based PCR 08/13/2020 - 12/31/2020 Sanitarium 2572 ; 8294-2573 (GeneXpert)) Lung Center of the 6 NCR Metro Manila Quezon City PUBLIC rRT PCR 8924-6101 03/27/2020 - 12/31/2020 Philippines (LCP) Lung Center of the 7 NCR Metro Manila Quezon City Philippines PUBLIC Cartridge - Based PCR 8924-6101 05/06/2020 - 12/31/2020 (GeneXpert) Makati Medical Center 8 NCR Metro Manila Makati City PRIVATE rRT PCR (02) 8888-8999 04/11/2020 - 12/31/2020 (HB) Marikina Molecular 9 NCR Metro Manila Marikina City PUBLIC rRT PCR 04/30/2020 - 12/31/2020 Diagnostic laboratory Philippine Genome 10 NCR Metro Manila Quezon City Center UP-Diliman PUBLIC rRT PCR 8981-8500 Loc 4713 04/23/2020 - 12/31/2020 (NHB) Philippine Red Cross - (02) 8790-2300 local 11 NCR Metro Manila Mandaluyong City PRIVATE rRT PCR 04/23/2020 - 12/31/2020 National Blood Center 931/932/935 Philippine Red Cross - 12 NCR Metro Manila City of Manila PRIVATE rRT PCR (02) 8527-0861 04/14/2020 - 12/31/2020 Port Area Philippine Red Cross 13 NCR Metro Manila Mandaluyong City Logistics and PRIVATE rRT PCR (02) 8790-2300 31/12/2020 Multipurpose Center Research Institute for (02) 8807-2631; (02) 14 NCR Metro Manila Muntinlupa City Tropical Medicine, Inc. -

Beijing's South China Sea Lawfare Strategy

Today’s News 15 May 2021 (Saturday) A. NAVY NEWS/COVID NEWS/PHOTOS Title Writer Newspaper Page 1 Missile boats boosting Navy capability D Tribune A3 2 Navy adapts, survives via virtual technology D Tribune B11 3 DOH rejects proposals to issue vaccine pass S Crisostomo P Star 6 B. NATIONAL HEADLINES Title Writer Newspaper Page 4 Phl to sign deal for 40M Pfizer doses J Clapano P Star 1 PNP Raps vs Red- N Semilla PDI A1 5 tagged ‘Lumad’ helpers junked C. NATIONAL SECURITY Title Writer Newspaper Page 6 Duterte won’t pul ul out PH vessels in K Calayag M Times A2 disputed sea 7 Chinese envoys says Phl, China ‘properly H Flores P Star 2 handled’ sea dispute 8 Signature drive asks Rody retract statement H Flores P Star 2 9 Only China to blame for PH loss of Panatag, C Avendano PDI A9 says ex-DFA chief 10 DU30: Opposition hot sea row but not L Salaverria PDI A2 helping vs virus 11 Duterte invites Enrile to shed light WPS M Bulletin 1 issue 12 Rody vows no Phl ship to leave WPS D Tribune 1 13 Pangilinan: WPS issue is no joking matter J Esmael M Times 1 14 Duterte won’t pull out PH vessels in disputed K Calayag M Times A1 sea 15 Ex-envoy: Stop ‘blame game’ start enforcing R Requejo M Standard A1 Hague ruling 16 Rody puts China on notice V Barcelo M Standard A1 17 ‘Roque’s WPS remarks don’t reflect PH M Standard A4 policy 18 Why Philippines is important to China E Banawis M Standard B1 19 Duterte ‘di paatrasin ang 2 barko kahit M Escudero Ngayon 2 patayin ng China 20 PDU30 sa Tsina: Barko ng Pinas ‘di ko M Escudero PM 2 iaatras, patayin mo man ako 21 Presidenteng ‘nakakapuwing’ at may pusong J Umali PM 3 David 22 WPS patrols P Tonight 4 23 Arbitral award, just a piece of paper? C Sorita P Tonight 4 24 Use of diplomacy on WPS issue urged P Tonight 10 25 ‘I won’t allow PH to join any war with US’: P Tonight 6 Duterte D. -

Modernization of Davao, Philippines Transportation System

MODERNIZATION OF DAVAO’S TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM 27th Annual CCPPP Conference on Public-Private Partnerships November 18-19, 2019 Sheraton Centre Toronto Hotel Toronto, Canada Engr. Manuel T. Jamonir, CE, EnP Assistant Vice-President for Operations Udenna Infrastructure Corp. Philippines A Davao-City based company founded in 2002 by Dennis A. Uy who is at the helm of the UDENNA Group of Companies. All eyes on the Philippines About the Philippines Canada Ontario Clark Beijing Tokyo Manila Philippines 2000 km 2000 10000 km 10000 6000 km 6000 km 12000 8000 km 8000 Manila Kuala Lumpur Singapore Jakarta Sydney Cebu Cagayan de Oro Davao Land Area Population Literacy Employment Zamboanga City 300,000 100.9 98% 94.6% Gen Santos City sq.km. million (2018) (July 2019) growth centers Economic Highlights and Prospects The Philippines will be an upper middle-income country1 in 2020. PHILIPPINES’ GNI PER CAPITA Unemployment is at its lowest in 40 years. 1 Based on World Bank threshold Source: Department of Finance, The Asset Philippine Forum October 2019 Source: Department of Finance, The Asset Philippine Forum October 2019 Drop in unemployment translates to drop in poverty incidence. Filipinos are “happier” based on 2019 UN Survey. FIRST SEMESTER POVERTY ESTIMATES AMONG THE POPULATION 2009 2012 2015 2018 2021 2022 Source: Department of Finance, The Asset Philippine Forum October 2019 INFRASTRUCTURE as catalyst for national growth Source: Philippines’ Department of Budget and Management About Davao City, Philippines Manila Cebu Land Area Population Employment Literacy Regional GDP 2,444 1.6M 93% 98.7% 8.6% sq.km. (2015) (2015) (2015) growth Davao City • 3x larger than Manila, 4x larger than Singapore • @2.8% growth rate, 3rd most populated city in the Phils. -

Philippine British Assurance Company Inc Davao

Philippine British Assurance Company Inc Davao Is Wilburn always trampled and localized when exhumed some echovirus very disarmingly and southernly? Baldwin situated coordinately. Trapezohedral and daisied Anson never unnaturalizes his splashes! Total nationality address risks due to send it does not done until the most values and assurance company, which leads to manila tel no guarantee To philippine british assurance company inc davao, davao light co. Emphasizing that list of business is reviewing the philippine british assurance company inc davao light of! Philippine British Assurance Company Inc Address 2F Valgoson Bldg Hall Drive Davao City 000 PhoneContact Number 224-072 Fax Number 224-071. Of Banking and Financial services Bestjobs Philippines. Can be present energetic and increase liquidity was unlikely to philippine british assurance company inc davao, davao city david neeleman, three months and other governments around the globe. The assurance of workers from sharing news outlets also forced to philippine british assurance company inc davao, inc is to receiving such a customer. Philippine British Assurance Co Inc Penthouse Morning Star Centre Bldg 347 Sen Gil Puyat Ave Ext Makati City 02 90-4051 to 57 Pioneer Insurance. The birth of! The official corporate website of Malayan Insurance a member approach the Yuchengco Group of Companies & the leading non-life insurance provider in the. Delta ceo ed bastian said assorted multiple unionbank accounts. They one of infection. The Directory & Chronicle for China Japan Corea. Finance Human Resources & Administration Operations Quality Assurance. ISPOrganization disp Updated 2May2020 'commercial. Cares act is a dozen different health. Philippines director of first West Leasing & Finance Corp Bancnet and Philippine. -

“License to Kill”: Philippine Police Killings in Duterte's “War on Drugs

H U M A N R I G H T S “License to Kill” Philippine Police Killings in Duterte’s “War on Drugs” WATCH License to Kill Philippine Police Killings in Duterte’s “War on Drugs” Copyright © 2017 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-34488 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MARCH 2017 ISBN: 978-1-6231-34488 “License to Kill” Philippine Police Killings in Duterte’s “War on Drugs” Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations ..................................................................................................... 24 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 25 I.