Mill Road Bridge Cambridge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

179 High Street, Cherry Hinton CB1 9LN Rah.Co.Uk 01223 323130

179 High Street, Cherry Hinton CB1 9LN A stunning first floor one bedroom apartment in a popular commuter spot offering easy access to Cambridge City centre. Entrance hall• Open plan living/dining/ kitchen • One bedroom • Bathroom • Garden • Allocated parking space • EPC Rating- C KEY FEATURES Recently refurbished Double Glazing rah.co.uk Excellent first time buyer or investment purchase 01223 323130 Off road parking Close to A14/A11 access The property is entered through its own front door and accessed via stairs which lead up to a central landing. The spacious sitting/kitchen/dining room is light, with windows to two aspects, and has a recently fitted kitchen with integrated appliances and a large number of fitted units. The bathroom has also been recently fitted with a modern white suite. To the front of the is a spacious double bedroom with built in storage. Outside the front garden is enclosed with a low-level fence and mostly laid to lawn. To the rear the property has allocated parking for one car and a bike storage shed. Location Cherry Hinton is a well served village within the Cambridge City boundary and is conveniently located just three miles south east of the City centre and about three miles from Addenbrookes Hospital and the railway station. There is a good selection of shops within the village, together with schooling for all age groups in the vicinity. In addition, Cherry Hinton Hall is located just off Cherry Hinton Road. Leasehold Length of lease- 125 years from 2009 It is written into the deeds that both properties have a 50/50 responsibility for maintenance. -

113 Cherry Hinton Road, Cambridge, CB1 7BS Guide

113 Cherry Hinton Road, Cambridge, CB1 7BS Guide Price £525,000 Freehold rah.co.uk 01223 323130 AN ATTRACTIVE THREE BEDROOM MID TERRACE BAY FRONTED EDWARDIAN HOUSE WITH A GARAGE AND LONG REAR GARDEN SITUATED IN THIS DESIRABLE RESIDENTIAL AREA CLOSE TO ADDENBROOKE’S HOSPITAL AND THE RAILWAY STATION Hall • sitting room • dining room • kitchen • bathroom • three double bedrooms • 70ft rear garden • detached garage • potential driveway parking • gas central heating This Edwardian mid terrace property is situated in a good location on the favoured south side of the City within easy reach of Addenbrooke’s, the railway station and a wide range of independent shops and restaurants. The property provides light and spacious accommodation arranged over two floors with an entrance hall leading to a sitting room with bay window, dining room, fitted kitchen with lobby giving access to a bathroom and separate wc. The first floor landing provides access to three generous double bedrooms. Outside, the property is set back from the road offering potential for off street parking, while the rear extends to about 70ft and is mainly laid to lawn and featuring a detached garage which is accessed via Derby Road. KEY FEATURES Edwardian bay fronted house Three double bedrooms Dining room and sitting room Long rear garden Detached garage Offered with no onward chain Gas central heating LOCATION Cherry Hinton Road is situated on the south side of the City and is conveniently placed for the City centre, railway station and Addenbrooke’s Hospital. Local shopping is available on Cherry Hinton Road at Cambridge Leisure providing a variety of restaurants, supermarkets, a multiplex cinema and gym. -

West Cambridge Site

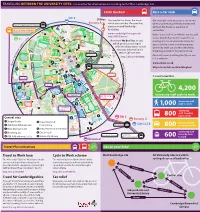

GGG RRR AAA SSS MMM EEE RRR EEE MMM uuu rrrr rrrr aaa yyyy GGG DDD NNN SSS CCC RRR OOO FFF TTT EEE ddd www aaa rrrr ddd ssss CROFT CCC ooo llll llll eeee ggg eeee HHH OOO LLL MMM EEE LLL NNN Allexandra CCC Caaa asss stttt tllll leee e CCoouurrrttt AAA llll eee xxx aaa nnn ddd rrr aaa CCC ooo uu A urrr ttt A CCaasstttlllee A CCoouu A urrrttt A A A A A 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 CC (((( CCCC aaaa mmm bbbb rrrrr iiiii dddd gggg eeee ssss hhhh iiiii rrrrr eeee 1 CA GGG aaa rrr ddd eee nnn sss AA 1 A 1 1 1 A 1 1 11 S 1 SSTCCCC oooo uuuu nnnn ttttt yyyy CCCC oooo uuuu nnnn cccc iiiii lllll )))) 3 3 T 3 3 3 TT 3 3 T 3 T 3 TRAVELLING BETWEENLL THE UNIVERSITY SITES SeeRD overleaf for information on travelling to the West Cambridge Site 4 4 R 4 E 4 4 E 4 4 4 EE SSSS hhhh iiiii rrrrr eeee HHHH aaaa lllll lllll 4 PP NNN P P O O K T KK T K ((( (CCC Caaa ammm bbb brrrr riiii iddd dggg geee esss shhh hiiii irrrr reee e T M ((CCaambbrrriiiddggeess M shhiiirrree M M M M AA M rrruu R nndd dee elll HHoo M ouussee R M AAA rrr uu R unnn ddd ee SS AArrruunnddeelllll HHHH oooo uuuu ssss eeee R S SSS S E E E E T SSS ttt t EEE ddd mmm uuu nnn ddd '''' 'sss s HHHH CCCC oooo uuuu nnnn ttttt yyyy CCCC ooo ouuu unnn nccc ciiii illll l))) ) TT Stt Edmund'''ss O Coouunncciiilll)) O O S O E E O HHoottteelll S O S O S E E E O HHH ooo ttt eee lll S O S HHoottteelll S E EE E EEEE EE L L L L L L LL L U H U H U U H U H U H U H U L H U H CCC ooo llll llll eeee ggg eeee LLL CCC C I I C I I I LLL I II I N L N N ST JJOHN'''S N N N SSS TTT JJJ OOO HHH NNN ''' SSS NN N ST JJOHN'''S ZZZ ZZZ -

South Area Neighbourhood Profile

Neighbourhood Profile Cambridge City South – September 2021 Wards: Cherry Hinton, Queen Edith’s and Trumpington © Crown copyright and database right 2021. Ordnance Survey Licence No. 100019730. Produced by: Cambridgeshire Constabulary: • Inspector Edward McNeill • Detective Sergeant Kiri Mazur / Sergeant Chris Bockham (from 6 September 2021) Community Safety Team, Cambridge City Council: • Lynda Kilkelly, Community Safety Manager • Maureen Tsentides, Anti-Social Behaviour Officer Contents 1. Introduction 3 Aim 3 Methodology 3 2. Current Areas of Concern 3 Continue work to tackle vehicle-related antisocial behaviour and driving across the South of the City; 3 Continue work (patrols and diverting young people away from crime and antisocial behaviour) across the South of the City, with specific focus on Trumpington Ward 4 Drug dealing, moped riding and anti-social behaviour around Cherry Hinton Rec and Cherry Hinton Hall 5 Bike theft in Nine Wells and Trumpington Ward. 5 3. Proactive Work and Emerging Issues 6 Cambridgeshire Constabulary 6 Cambridge City Council 7 4. Additional Information 8 5. Recommendations 8 2 1. Introduction Aim The aim of the Neighbourhood profile update is to provide an overview of action taken since the last reporting period, identify on-going and emerging crime and disorder issues, and provide recommendations for future areas of concern and activity in order to facilitate effective policing and partnership working in the area. The document should be used to inform multi-agency neighbourhood panel meetings and neighbourhood policing teams, so that issues can be identified, effectively prioritised and partnership problem solving activity undertaken. Methodology This document was produced using data received from the following sources: • The Safer Neighbourhood Policing Team for the area; • The City Council’s Community Safety Team; • The general public, via online and telephone crime and intelligence reporting; and • Consultation with elected Ward and County members. -

Land North of Cherry Hinton

LAND NORTH OF CHERRY HINTON SUPPLEMENTARY PLANNING DOCUMENT December 2018 © Terence O’Rourke Ltd 2018. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced in any form or stored in a retrieval system without the prior written consent of the copyright holder. All figures (unless otherwise stated) © Terence O’Rourke Ltd 2018. Based upon the 2017 Ordnance Survey mapping with the permission of the Ordnance Survey on behalf of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office © Crown Copyright Terence O’Rourke Ltd Licence number 100019980. 2 LAND NORTH OF CHERRY HINTON SUPPLEMENTARY PLANNING DOCUMENT LAND NORTH OF CHERRY HINTON SUPPLEMENTARY PLANNING DOCUMENT 01 INTRODUCTION 2 03 THE SITE AND SURROUNDING AREA 12 05 FRAMEWORK PRINCIPLES AND 44 MASTERPLAN Overview of the Site 2 Surrounding areas and adjacent uses 12 Purpose of the development framework 2 Transport and movement 14 Overview 44 Structure of the development brief 2 Services and facilities in Cambridge 16 Summary of consultation 45 Achieving a high quality development 6 Local facilities 17 Movement 46 Green infrastructure 20 Environmental considerations & sustainability 8 02 PLANNING POLICY CONTEXT Open spaces and recreation 21 site-wide sustainability 56 Introduction 8 Ecology 22 Surface water drainage strategy 58 Local plan policies 9 Local statutory and non-statutory designations 23 Landscape and OS 62 Green belt 11 Historic growth and urban grain 24 Land uses 67 Neighbourhood context analysis 25 Character and form 69 The Site 30–40 Development and principles 72 Summary of site constraints -

Briefing Note Findings for Cambridge for IMD Index 2015

Briefing Note Findings for Cambridge for IMD Index 2015 Foreword The Department of Communities and Local Government (DCLG) published the English Indices of Deprivation 2015 (ID 2015) on the 30 September 2015. The indices are combined into the composite Index of Multiple Deprivation 2015 (IMD 2015). Documents, including an Infographic, Guidance and the Main Findings can be found here: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2015 An IMD score for an area is taken from the average score for seven domains of deprivation, each with a different weighting. This briefing note will highlight the findings from IMD Index scores, including sub-index and the domains, looking more in depth at the highly ranked areas and their characteristics. Contents Item Heading Page No. 1. Research Group IMD Summary 2 2. Main Findings for IMD Cambridgeshire 2 3. Summary Findings for Cambridge 3 4. Roads covered by ten lowest ranked LSOAs 4 5. Changes in IMD Rankings 6 6. IMD Deciles 7 7. Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index 9 8. Income Deprivation Affecting Older People Index (IDAOP) 12 9. OAC Portraits Description of the City’s 20% (worst) LSOAs IMD15 15 10. ACORN Consumer Classifications for 10 highest Ranked LSOAs 17 11. Cambridge IMD Domains 27 12. A Closer look at the Living Environment Domain 28 13. Looking at Cambridge IMD Domains by Ward 29 14. Data Tables 43 1 1. Research Group IMD Summary Cambridgeshire Research Group has provided a Summary Report looking at IMD data for Cambridgeshire and comparing the differences in national and local ranks and deciles from IMD 2010 to IMD 2015. -

This Branch Is Closing – but We're Still Here to Help

1 | 1 This branch is closing – but we’re still here to help Our Cambridge Cherry Hinton Road branch is closing on Friday 27 November 2020. Branch closure feedback, and alternative ways to bank 2 | 3 Sharing branch closure feedback We’re now nearing the closure of the Cambridge Cherry Hinton Road branch of Barclays. Our first booklet explained why the branch is closing, and gave information on other banking services that we hope will be convenient for you. We do understand that the decision to close a branch affects different communities in different ways, so we’ve spoken to people in your community to listen to their concerns. We wanted to find out how your community, and particular groups within it, could be affected when the branch closes, and what we could do to help people through the transition from using the branch with alternative ways to carry out their banking requirements. There are still many ways to do your banking, including in person at another nearby branch, at your local Post Office or over the phone on 0345 7 345 3452. You can also go online to barclays.co.uk/waystobank to learn about your other options. Read more about this on page 6. If you still have any questions or concerns about these changes, now or in the future, then please feel free to get in touch with us by: Speaking to us in any of our nearby branches Contacting Anthony Ridge, your Market Director for Cambridgeshire. Email: [email protected] We contacted the following groups: We asked each of the groups 3 questions – here’s what they said: MP: Daniel -

14 Carrick Close, Cherry Hinton, Cambridge, CB1 8RQ Guide Price

14 Carrick Close, Cherry Hinton, Cambridge, CB1 8RQ Guide Price £435,000 Freehold rah.co.uk 01223 323130 AN ATTRACTIVE THREE BEDROOM SEMI-DETACHED MODERN HOUSE WITH INTEGRAL GARAGE AND PARKING OCCUPYING A DELIGHTFUL POSITION IN A SOUGHT-AFTER CUL-DE-SAC OPPOSITE CHERRY HINTON HALL. NO ONWARD CHAIN 3 bedrooms • en suite & dressing room to master bedroom • family bathroom • sitting/dining room • kitchen • cloakroom • integral garage • driveway parking • rear garden Occupying a peaceful location in a desirable tree-lined cul-de-sac on the southern side of the City, opposite Cherry Hinton Hall, this attractive modern semi-detached house offers spacious, open and light-filled accommodation, ideal for families or professionals connected to Addenbrooke’s Hospital and ARM Ltd. The entrance hall leads to the open plan sitting/dining room which enjoys dual aspects and has an attractive rear bay window which provides views to the rear garden. The refitted modern kitchen offers a range of matching storage cupboards and leads to the WC, integral garage and provides access to the rear garden. Upstairs, the first floor landing leads to the family bathroom and three bedrooms. The master bedroom provides a dressing area and en suite facilities. Outside, there is driveway parking for one vehicle to the front of the property. The rear garden is fully enclosed and very private. There Is a patio area, lawn and established borders of various shrubs and small trees. KEY FEATURES Desirable cul-de-sac opposite Cherry Hinton Hall Master bedroom suite Open plan living accommodation Garage and parking No onward chain LOCATION Carrick Close is a quiet cul-de-sac tucked away just off Cherry Hinton Road opposite the grounds of Cherry Hinton Hall and within easy reach of Addenbrookes Hospital, which is about one and a half miles away. -

![Site Assessment Rejected Sites Broad Location 8 [PDF, 0.8MB]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8494/site-assessment-rejected-sites-broad-location-8-pdf-0-8mb-2678494.webp)

Site Assessment Rejected Sites Broad Location 8 [PDF, 0.8MB]

Site Assessments of Rejected Green Belt Sites for Broad Location 8 500 Cambridge City Council / South Cambridgeshire District Council Green Belt Site and Sustainability Appraisal Assessment Proforma Site Information Broad Location 8 Land east of Gazelle Way Site reference number(s): SC296 Site name/address: Land east of Gazelle Way Functional area (taken from SA Scoping Report): City only Map: Site description: Large flat arable fields with low boundary hedges to Gazelle Way. Woodland belt adjoins Cherry Hinton Road, more significant hedges elsewhere. Suburban residential to west of Gazelle Way. Major electricity transformer station to south at junction of Gazelle Way and Fulborn Old Drift with two lines of pylons, one high, metal pylon line to eastern field boundary and a second double line of lower power, wooden pylons crosses the middle of the site. Tesco supermarket to south. Prefab housing site adjoins Fulbourn Old Drift to the east. The land very gently falls away towards the east. Current use: Agricultural Proposed use(s): Residential Site size (ha): 21 approximately Assumed net developable area: 10.5 approximately Assumed residential density: 40 dph Potential residential capacity: 420 Site owner/promoter: Known Landowner has agreed to promote site for development?: Landowners appear to support development Site origin: Green Belt assessment 501 Relevant planning history: Planning permission granted in 1981 for land fronting onto the northern half of Gazelle Way for housing development, open space and schools. A subsequent planning permission in 1985 limited built development to the west of Gazelle Way only, which was implemented. The Panel Report into the draft Cambridgeshire & Peterborough Structure Plan published in February 2003 considered proposals for strategic large scale development to the east of Cambridge Airport around Teversham and Fulbourn. -

CAMBRIDGE STREET-NAMES Their Origins and Associations Ffffffff3;2Vvvvvvvv

CAMBRIDGE STREET-NAMES Their Origins and Associations ffffffff3;2vvvvvvvv RONALD GRAY AND DEREK STUBBINGS The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain © Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Monotype Fournier 12/15 pt System QuarkXPress™ [SE] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data p. cm. ISBN 0 521 78956 7 paperback Contents Acknowledgements page vii What do street-names mean? viii How can you tell? xiii Prehistoric 1 Roman 1 Anglo-Saxon 4 Medieval 8 Barnwell 20 Town and gown 24 The beginning of the University 26 The Reformation 29 The Renaissance and science 36 The Civil War 44 The eighteenth century 47 War against Napoleon 55 George IV and his wife 57 Queen Victoria’s reign 57 The British Empire 64 Coprolite mining 65 Coal, corn and iron 65 Brewers 68 Trams and buses 71 Nineteenth-century historians, antiquaries and lawyers 72 Nineteenth-century scientists 74 Nineteenth-century -

West Area Ward Profile 2019

West Area Ward Profile 2019 1 Contents Introduction Pg. 3 Demographics + Foodbank data Pg. 4-10 Benefit data Pg. 11 Housing tenures Pg.12-13 Isolation and loneliness Pg. 14 Sheltered housing Pg 14 Community Facilities Pg. 15-16 Parks and open spaces Pg. 17-18 Health data and services Pg. 19-20 Community Safety and crime data Pg. 20-21 Schools and services based in area Pg. 22-25 Community / voluntary sector organisations Pg. 25 Planned future growth Pg. 26 Key challenges, strengths and assets Pg. 27 Links / references Pg.27 Map Pg. 28 2 Introduction This Neighbourhood Profile for the West area of the city covers the following wards: Castle, Newnham, and Market. The profiles have been collated by the City Council’s Neighbourhood Community Development Team (NCDT) as a tool to developing work plans for the coming year and beyond. The profiles aim to capture key facts and statistics about the area, services that are delivered by the Council and other statutory and voluntary sector partners, key community groups and activities in the area as well as the perceived gaps in provision or areas of need. Data collated contains some information from the latest census therefore areas of new housing growth such as Eddington may be missing from the data-sets. The NCDT has recently realigned its community development resources to work in the areas of highest need in the city. Key themes from the profiling exercise will help to shape the work priorities for the team for the coming year. Our thanks to everyone who has provided information included in the -

Advisory Visit Cherry Hinton Brook, Cambridge 18Th July 2017

Advisory Visit Cherry Hinton Brook, Cambridge 18th July 2017 1.0 Introduction This report is the output of a site visit undertaken by Rob Mungovan of the Wild Trout Trust to the Cherry Hinton Brook on 18th July 2017, a subsequent visit was made on the evening of 24th July to explore the brook’s lower reaches and connection to the River Cam. Comments in this report are based on observations on the day of the site visits and discussions with Guy Belcher, Cambridge City Council’s Ecologist. The positive management and restoration of the Brook are primary objectives of the local conservation group, the Friends of Cherry Hinton Brook. This report will be reviewed, and hopefully, implemented by the Friends. Note that this report does not follow normal convention in so far that all pictures (unless stated) are taken looking upstream. This was necessary in order to enable the visit to be undertaken whilst moving upstream into non- turbid water. 2.0 Catchment and walkover observations River Cherry Hinton Brook Waterbody Name Cherry Hinton Brook Waterbody ID GB105033042670 Management Catchment Cam and Ely Ouse River Basin District Anglian Current Ecological Quality Moderate U/S Grid Ref inspected TL48255 56473 D/S Grid Ref inspected TL 47246 60080 Length of river inspected 3.78km Table 1 – watercourse attributes Map 1 – The catchment and general location of the Cherry Hinton Brook Th e Cherry Hinton Brook rises from chalk springs at Giant’s Grave, Cherry Hinton and flows in a northerly direction through an increasingly urban catchment. On many maps the lower parts of the Cherry Hinton Brook are referred to as the Coldham’s Brook.