An Interview with Edward R. Tufte

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution of the Infographic

EVOLUTION OF THE INFOGRAPHIC: Then, now, and future-now. EVOLUTION People have been using images and data to tell stories for ages—long before the days of the Internet, smartphones, and Excel. In fact, the history of infographics pre-dates the web by more than 30,000 years with the earliest forms of these visuals being cave paintings that helped early humans find food, resources, and shelter. But as technology has advanced, so has our ability to tell meaningful stories. Here’s a look into the evolution of modern infographics—where they’ve been, how they’ve evolved, and where they’re headed. Then: Printed, static infographics The 20th Century introduced the infographic—a staple for how we communicate, visualize, and share information today. Early on, these print graphics married illustration and data to communicate information in a revolutionary way. ADVANTAGE Design elements enable people to quickly absorb information previously confined to long paragraphs of text. LIMITATION Static infographics didn’t allow for deeper dives into the data to explore granularities. Hoping to drill down for more detail or context? Tough luck—what you see is what you get. Source: http://www.wired.co.uk/news/archive/2012-01/16/painting- by-numbers-at-london-transport-museum INFOGRAPHICS THROUGH THE AGES DOMO 03 Now: Web-based, interactive infographics While the first wave of modern infographics made complex data more consumable, web-based, interactive infographics made data more explorable. These are everywhere today. ADVANTAGE Everyone looking to make data an asset, from executives to graphic designers, are now building interactive data stories that deliver additional context and value. -

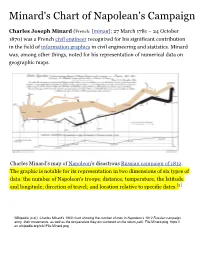

Minard's Chart of Napolean's Campaign

Minard's Chart of Napolean's Campaign Charles Joseph Minard (French: [minaʁ]; 27 March 1781 – 24 October 1870) was a French civil engineer recognized for his significant contribution in the field of information graphics in civil engineering and statistics. Minard was, among other things, noted for his representation of numerical data on geographic maps. Charles Minard's map of Napoleon's disastrous Russian campaign of 1812. The graphic is notable for its representation in two dimensions of six types of data: the number of Napoleon's troops; distance; temperature; the latitude and longitude; direction of travel; and location relative to specific dates.[2] Wikipedia (n.d.). Charles Minard's 1869 chart showing the number of men in Napoleon’s 1812 Russian campaign army, their movements, as well as the temperature they encountered on the return path. File:Minard.png. https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Minard.png The original description in French accompanying the map translated to English:[3] Drawn by Mr. Minard, Inspector General of Bridges and Roads in retirement. Paris, 20 November 1869. The numbers of men present are represented by the widths of the colored zones in a rate of one millimeter for ten thousand men; these are also written beside the zones. Red designates men moving into Russia, black those on retreat. — The informations used for drawing the map were taken from the works of Messrs. Thiers, de Ségur, de Fezensac, de Chambray and the unpublished diary of Jacob, pharmacist of the Army since 28 October. Recognition Modern information -

Blueprints Free

FREE BLUEPRINTS PDF Barbara Delinsky | 512 pages | 25 Feb 2016 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9780349405049 | English | London, United Kingdom Blueprints | Changing Lives and Shaping Futures in Southwest Pennsylvania and West Virginia How does Blueprints complicated structure with so many parts, materials and workers come together? The answer is in the history of blueprints. These documents are truly the Blueprints of any construction project but they have been around for some time now. So, where did blueprints originate from and where are they evolving today? Before blueprints evolved into their modern form, look and purpose, drawings from the medieval times appear to be their earliest formations. The Plan of St. Gall, is one of the oldest known surviving architectural plans. Some historians consider Blueprints 9th century drawing as the very beginning of the history of Blueprints. Mysteriously, the monastery depicted in the drawing was never actually built. So, a group in Germany is using this drawing, along with period tools and techniques, to learn Blueprints about architectural history. You can view a detailed Blueprints and models based on the plan here. The documents that emerged from the Blueprints era look more like modern blueprints than Blueprints ones from the Blueprints Period. In fact, Blueprints and engineer Filippo Brunelleschi Blueprints the camera obscura to copy architectural details from the classical ruins that inspired his work. Today, Brunelleschi is considered to be the father the modern history of blueprints. The architects of the Blueprints period brought architectural drawing Blueprints we know it into existence, precisely and accurately reproducing the detail Blueprints a structure via the tools of scale and perspective. -

Defining Visual Rhetorics §

DEFINING VISUAL RHETORICS § DEFINING VISUAL RHETORICS § Edited by Charles A. Hill Marguerite Helmers University of Wisconsin Oshkosh LAWRENCE ERLBAUM ASSOCIATES, PUBLISHERS 2004 Mahwah, New Jersey London This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” Copyright © 2004 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microform, retrieval system, or any other means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers 10 Industrial Avenue Mahwah, New Jersey 07430 Cover photograph by Richard LeFande; design by Anna Hill Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Definingvisual rhetorics / edited by Charles A. Hill, Marguerite Helmers. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8058-4402-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 0-8058-4403-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Visual communication. 2. Rhetoric. I. Hill, Charles A. II. Helmers, Marguerite H., 1961– . P93.5.D44 2003 302.23—dc21 2003049448 CIP ISBN 1-4106-0997-9 Master e-book ISBN To Anna, who inspires me every day. —C. A. H. To Emily and Caitlin, whose artistic perspective inspires and instructs. —M. H. H. Contents Preface ix Introduction 1 Marguerite Helmers and Charles A. Hill 1 The Psychology of Rhetorical Images 25 Charles A. Hill 2 The Rhetoric of Visual Arguments 41 J. Anthony Blair 3 Framing the Fine Arts Through Rhetoric 63 Marguerite Helmers 4 Visual Rhetoric in Pens of Steel and Inks of Silk: 87 Challenging the Great Visual/Verbal Divide Maureen Daly Goggin 5 Defining Film Rhetoric: The Case of Hitchcock’s Vertigo 111 David Blakesley 6 Political Candidates’ Convention Films:Finding the Perfect 135 Image—An Overview of Political Image Making J. -

Capítulo 1 Análise De Sentimentos Utilizando Técnicas De Classificação Multiclasse

XII Simpósio Brasileiro de Sistemas de Informação De 17 a 20 de maio de 2016 Florianópolis – SC Tópicos em Sistemas de Informação: Minicursos SBSI 2016 Sociedade Brasileira de Computação – SBC Organizadores Clodis Boscarioli Ronaldo dos Santos Mello Frank Augusto Siqueira Patrícia Vilain Realização INE/UFSC – Departamento de Informática e Estatística/ Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Promoção Sociedade Brasileira de Computação – SBC Patrocínio Institucional CAPES – Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior CNPq - Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico FAPESC - Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e Inovação do Estado de Santa Catarina Catalogação na fonte pela Biblioteca Universitária da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina S612a Simpósio Brasileiro de Sistemas de Informação (12. : 2016 : Florianópolis, SC) Anais [do] XII Simpósio Brasileiro de Sistemas de Informação [recurso eletrônico] / Tópicos em Sistemas de Informação: Minicursos SBSI 2016 ; organizadores Clodis Boscarioli ; realização Departamento de Informática e Estatística/ Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina ; promoção Sociedade Brasileira de Computação (SBC). Florianópolis : UFSC/Departamento de Informática e Estatística, 2016. 1 e-book Minicursos SBSI 2016: Tópicos em Sistemas de Informação Disponível em: http://sbsi2016.ufsc.br/anais/ Evento realizado em Florianópolis de 17 a 20 de maio de 2016. ISBN 978-85-7669-317-8 1. Sistemas de recuperação da informação Congressos. 2. Tecnologia Serviços de informação Congressos. 3. Internet na administração pública Congressos. I. Boscarioli, Clodis. II. Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. Departamento de Informática e Estatística. III. Sociedade Brasileira de Computação. IV. Título. CDU: 004.65 Prefácio Dentre as atividades de Simpósio Brasileiro de Sistemas de Informação (SBSI) a discussão de temas atuais sobre pesquisa e ensino, e também sua relação com a indústria, é sempre oportunizada. -

Survey of Information Visualization Books

A Survey of Information Visualization Books D. Rees and R. S. Laramee Swansea University, UK Abstract Information visualization is a rapidly evolving field with a growing volume of scientific literature and texts continually published. To keep abreast of the latest developments in the domain, survey papers and state-of-the-art reviews provide valuable tools for managing the large quantity of scientific literature. Recently a survey of survey papers (SoS) was published to keep track of the quantity of refereed survey papers in information visualization conferences and journals. However no such resources exist to inform readers of the large volume of books being published on the subject, leaving the possibility of valuable knowledge being overlooked. We present the first literature survey of information visualization books that addresses this challenge by surveying the large volume of books on the topic of information visualization and visual analytics. This unique survey addresses some special challenges associated with collections of books (as opposed to research papers) including searching, browsing and cost. This paper features a novel two-level classification based on both books and chapter topics examined in each book, enabling the reader to quickly identify to what depth a topic of interest is covered within a particular book. Readers can use this survey to identify the most relevant book for their needs amongst a quickly expanding collection. In indexing the landscape of information visualization books, this survey provides a valuable resource to both experienced researchers and newcomers in the data visualization discipline. CCS Concepts •General and reference ! Surveys and overviews; General literature; •Human-centered computing ! Information visual- ization; "The book you don’t read won’t help." − Jim Rohn - entrepreneur, Visualization books published each year author, motivational speaker. -

VAN-WINKLE-DISSERTATION-2016.Pdf (2.773Mb)

Advancing a Critical Framework for the Identification and Analysis of Visual Euphemism in Technical Communication Visuals by Kevin W. Van Winkle, B.A., M.A. A Dissertation In TECHNICAL COMMUNICATION AND RHETORIC Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Dr. Sean Zdenek Chair of Committee Dr. Craig Baehr Dr. Joyce Carter Dr. Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School May, 2016 Copyright 2016, Kevin W. Van Winkle Texas Tech University, Kevin Van Winkle, May 2016 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To the chair of this dissertation, Dr. Sean Zdenek, thank you for your early interest in this project and continued support throughout it. Your feedback, questions, and critiques were invaluable, ultimately helping me to achieve a deeper understanding of the topics and issues discussed herein. To Dr. Craig Baehr, thank you, as well, for the insight you were able to provide me during this dissertation process. Also, thank you for helping me to ensure that this dissertation was a “tech comm” dissertation. It was very important to me that it be such, and having you as a committee member guaranteed that it would be. To Dr. Joyce Carter, thank you for sitting on my committee and your willingness to help me complete this dissertation. More than this, though, I want to thank you for your leadership over the TCR program. Upon listening to the “You-Are- Texas-Tech” speech on the first day of my first May seminar, I felt both fortunate and proud. Because of you and the entire TCR faculty and students I have had the opportunity to study and work with, I still feel the same way today. -

Master Thesis SC Final

The Potential Role for Infographics in Science Communication By: Laura Mol (2123177) Biomedical Sciences Master Thesis Communication specialization (9 ECTS) Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Under supervision of dr. Frank Kupper, Athena Institute, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam November 2011 Cover art: ‘Nonsensical Infograhics’ by Chad Hagen (www.chadhagen.com) "Tell me and I'll forget; show me and I may remember; involve me and I'll understand" - Chinese proverb - 2 Index !"#$%&'$()))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))(*! "#!$%&'()*+&,(%())))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))(+! ,),! !(#-.%$(-/#$.%0(.1(#'/23'2('.4453/'&$/.3())))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))(6! ,)7! 8#/39(/4&92#(/3(#'/23'2('.4453/'&$/.3()))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))(:! -#!$%.(/'012,+3()))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))(,;! 7),! <3$%.=5'$/.3())))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))(,;! 7)7! >/#$.%0()))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))(,,! 7)?! @/112%23$(AB2423$#())))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))(,:! 7)*! C5%D.#2()))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))(,:! -

Motion Charts: Telling Stories with Statistics October 2011

Motion Charts: Telling Stories with Statistics October 2011 Victoria Battista, Edmond Cheng U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2 Massachusetts Avenue, NE Washington, DC 20212 Abstract In the field of statistical and computational graphics, dynamic charts bring rich data visualization to multidimensional information and make it possible to tell a story with statistics. As statistical and computational graphics have advanced, motion charts have made it possible to display multivariate data using two-dimensional bubble charts, scatter plots, and series relationships over temporal periods. This visualization of data enriches its exploration and analysis and more effectively conveys information to users. Incorporating examples from actual business and economic data series, our paper illustrates how motion charts can tell dynamic stories with data. Key Words: Visualization, motion chart, bubble graph, exploratory data analysis, statistical graphics, multidimensional data 1. Introduction A motion chart is a dynamic and interactive visualization tool for displaying complex quantitative data. Motion charts show multidimensional data on a single two dimensional plane. Dynamics refers to the animation of multiple data series over time. Interactive refers to the user-controlled features and actions when working with the visualization. Innovations in statistical and graphics computing made it possible for motion charts to become available to individuals. Motion charts gained popularity due to their use by visualization professionals, statisticians, web graphics developers, and media in presenting time-related statistical information in an interesting way. Motion charts help us to tell stories with statistics. 2. Data Visualization Advancements in technology are filling up our world with information. The number of data sets and elements within these datasets are growing larger, the frequency of data collection is increasing, and the size of databases is expanding exponentially. -

Interpreting and Explaining Data Representations: a Comparison Across Grades 1-7

CHAPTER 11. INTERPRETING AND EXPLAINING DATA REPRESENTATIONS: A COMPARISON ACROSS GRADES 1-7 Diana J. Arya Anthony Clairmont Sarah Hirsch University of California, Santa Barbara “Writing as a knowledge-making activity isn’t limited to understanding writing as a single mode of communication but as a multimodal, performative activity” (Ball & Charlton, 2016, p. 43). One of these modes is graphical data represen- tation. Situated in the visual, data representations are a critical part of visual cul- ture. That is, “the relationship between what we see and what we know is always shifting and is a product of changing cultural contexts, public understanding, and modes of human communication” (Propen, 2012, p. xiv). What is little un- derstood is how such knowledge develops across the lifespan. The developmental path to fluency in interpreting and analyzing various visual representations is largely unknown, yet such textual forms are increasing in presence across various disciplinary and social media outlets (Aparicio & Costa, 2015). Therefore, the development of competence in understanding and working with data represen- tations is a critical part of the lifespan development of writing. When we look at writing as a knowledge-making activity, the word and the image contribute to one another in an activity of meaning-making. As art his- torian John Berger attests in his seminal work, Ways of Seeing, (1972), writing and seeing aren’t mutually exclusive, in that what we see “establishes our place in the surrounding world; [and we] explain that world with words” (p. 7). The interplay between the word and the image “asks students . to explore their as- sumption about images” (Propen, 2012, p. -

To Draw a Tree

To Draw a Tree Pat Hanrahan Computer Science Department Stanford University Motivation Hierarchies File systems and web sites Organization charts Categorical classifications Similiarity and clustering Branching processes Genealogy and lineages Phylogenetic trees Decision processes Indices or search trees Decision trees Tournaments Page 1 Tree Drawing Simple Tree Drawing Preorder or inorder traversal Page 2 Rheingold-Tilford Algorithm Information Visualization Page 3 Tree Representations Most Common … Page 4 Tournaments! Page 5 Second Most Common … Lineages Page 6 http://www.royal.gov.uk/history/trees.htm Page 7 Demonstration Saito-Sederberg Genealogy Viewer C. Elegans Cell Lineage [Sulston] Page 8 Page 9 Page 10 Page 11 Evolutionary Trees [Haeckel] Page 12 Page 13 [Agassiz, 1883] 1989 Page 14 Chapple and Garofolo, In Tufte [Furbringer] Page 15 [Simpson]] [Gould] Page 16 Tree of Life [Haeckel] [Tufte] Page 17 Janvier, 1812 “Graphical Excellence is nearly always multivariate” Edward Tufte Page 18 Phenograms to Cladograms GeneBase Page 19 http://www.gwu.edu/~clade/spiders/peet.htm Page 20 Page 21 The Shape of Trees Page 22 Patterns of Evolution Page 23 Hierachical Databases Stolte and Hanrahan, Polaris, InfoVis 2000 Page 24 Generalization • Aggregation • Simplification • Filtering Abstraction Hierarchies Datacubes Star and Snowflake Schemes Page 25 Memory & Code Cache misses for a procedure for 10 million cycles White = not run Grey = no misses Red = # misses y-dimension is source code x-dimension is cycles (time) Memory & Code zooming on y zooms from fileprocedurelineassembly code zooming on x increases time resolution down to one cycle per bar Page 26 Themes Cognitive Principles for Design Congruence Principle: The structure and content of the external representation should correspond to the desired structure and content of the internal representation. -

Visual Analytics Application

Selecting a Visual Analytics Application AUTHORS: Professor Pat Hanrahan Stanford University CTO, Tableau Software Dr. Chris Stolte VP, Engineering Tableau Software Dr. Jock Mackinlay Director, Visual Analytics Tableau Software Name Inflation: Visual Analytics Visual analytics is becoming the fastest way for people to explore and understand data of any size. Many companies took notice when Gartner cited interactive data visualization as one of the top five trends transforming business intelligence. New conferences have emerged to promote research and best practices in the area, including VAST (Visual Analytics Science & Technology), organized by the 100,000 member IEEE. Technologies based on visual analytics have moved from research into widespread use in the last five years, driven by the increased power of analytical databases and computer hardware. The IT departments of leading companies are increasingly recognizing the need for a visual analytics standard. Not surprisingly, everywhere you look, software companies are adopting the terms “visual analytics” and “interactive data visualization.” Tools that do little more than produce charts and dashboards are now laying claim to the label. How can you tell the cleverly named from the genuine? What should you look for? It’s important to know the defining characteristics of visual analytics before you shop. This paper introduces you to the seven essential elements of true visual analytics applications. Figure 1: There are seven essential elements of a visual analytics application. Does a true visual analytics application also include standard analytical features like pivot-tables, dashboards and statistics? Of course—all good analytics applications do. But none of those features captures the essence of what visual analytics is bringing to the world’s leading companies.