SAD= Sustainable and Delightful: a Designer's Guide to Sustainable Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queensland Public Boat Ramps

Queensland public boat ramps Ramp Location Ramp Location Atherton shire Brisbane city (cont.) Tinaroo (Church Street) Tinaroo Falls Dam Shorncliffe (Jetty Street) Cabbage Tree Creek Boat Harbour—north bank Balonne shire Shorncliffe (Sinbad Street) Cabbage Tree Creek Boat Harbour—north bank St George (Bowen Street) Jack Taylor Weir Shorncliffe (Yundah Street) Cabbage Tree Creek Boat Harbour—north bank Banana shire Wynnum (Glenora Street) Wynnum Creek—north bank Baralaba Weir Dawson River Broadsound shire Callide Dam Biloela—Calvale Road (lower ramp) Carmilla Beach (Carmilla Creek Road) Carmilla Creek—south bank, mouth of creek Callide Dam Biloela—Calvale Road (upper ramp) Clairview Beach (Colonial Drive) Clairview Beach Moura Dawson River—8 km west of Moura St Lawrence (Howards Road– Waverley Creek) Bund Creek—north bank Lake Victoria Callide Creek Bundaberg city Theodore Dawson River Bundaberg (Kirby’s Wall) Burnett River—south bank (5 km east of Bundaberg) Beaudesert shire Bundaberg (Queen Street) Burnett River—north bank (downstream) Logan River (Henderson Street– Henderson Reserve) Logan Reserve Bundaberg (Queen Street) Burnett River—north bank (upstream) Biggenden shire Burdekin shire Paradise Dam–Main Dam 500 m upstream from visitors centre Barramundi Creek (Morris Creek Road) via Hodel Road Boonah shire Cromarty Creek (Boat Ramp Road) via Giru (off the Haughton River) Groper Creek settlement Maroon Dam HG Slatter Park (Hinkson Esplanade) downstream from jetty Moogerah Dam AG Muller Park Groper Creek settlement Bowen shire (Hinkson -

Loders Creek Catchment Hydraulic Study

Loders Creek Catchment Hydraulic Study August 2016 1 Title: Loders Creek Catchment Hydraulic Study Author: Study for: City Planning Branch Planning and Environment Directorate The City of Gold Coast File Reference: WF28/44/01(P4) TRACKS #45330050 Version history Changed by Reviewed by & Version Comments/Change & date date 1.0 Draft 2.0 Update DTM 3.0 Edited 4.0 Edited Distribution list Name Title Directorate Branch Version 4 – August 18 TRACKS-#45330050-v4-LODERS_CREEK_HYDRAULIC_STUDY_2015 Page 2 of 72 Executive Summary The Loders Creek catchment is the smallest catchment (9.6km2) on the Gold Coast which experiences regional flooding. Loders Creek drains into the Broadwater system and contains small tributaries which are susceptible to breaches during heavy downpours. Loders Creek contains a small embankment dam which was constructed in the early 1970’s to mitigate flooding impacts in the lower reaches and to allow further urbanisation of the Broadwater foreshore. This Loders Creek catchment hydraulic study is the result of numerous studies undertaken over a number of years to determine a flood planning level for the catchment. This study’s output is an updated Loders Creek hydraulic model which has been used to develop a flood map for the City of Gold Coast’s City Plan 2015 designated flood level (DFL). DHI’s MIKE software suites have been used to build the hydraulic model. MIKE21 calculates complex flows and represents floodplain storage in the 2D domain whilst MIKE11 represents flow constrictions of hydraulic structures in the 1D domain. MIKE Flood was used to combine the two dynamic software platforms of MIKE21 and MIKE11. -

2 Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Assessment Approach

Environmental Impact Statement BULGA OPTIMISATION PROJECT APRIL 2013 xs ra a Volume 6A APPENDIX 13a Part 1 Bulga Optimisation Project Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Assessment Final Report, April 2013 Bulga Optimisation Project Final Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Assessment Prepared by Connect for Effect Pty Limited on behalf of Bulga Coal Management Pty Limited Connect for Effect Pty Ltd 116 Serrata Circuit Banksia Village Forest Lake Queensland 4078 Ph.: 07 3333 2283 Email: [email protected] Website: www.connectforeffect.com.au Connect For Effect Pty Ltd Job NoCFE11 Final Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Assessment /Report No1/Final April 2013 Page i Bulga Optimisation Project Final Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Assessment Disclaimer Every reasonable effort has been made to ensure the content of this this document is correct at the time of its preparation on 18 April 2013. Connect for Effect Pty Ltd, its agents and employees, do not accept any responsibility and shall have no liability, consequential or otherwise, of any kind, arising from the use of or reliance on any of the information contained herein. COPYRIGHT Copyright of the drawings, information and data recorded in this document (i.e. all information) is the property of Connect for Effect Pty Ltd. This document and all information contained herein are solely for the use of the authorised recipient. This document may not be used, copied or reproduced in whole or part thereof for any purpose other than that for which it was supplied by Connect for Effect Pty Ltd unless written permission is granted by Connect for Effect Pty Ltd and is duly attributed. This report has been prepared in accordance with Clause 80C of the National Parks and Wildlife Regulation 2009. -

Queensland Government Gazette

Queensland Government Gazette PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ISSN 0155-9370 Vol. 377] Friday 16 March 2018 Gazette Closing times for the Easter Period Calendar .BSDIoApril 2 .BSDI Monday 5VFTEBZ8FEOFTEBZ 5IVSTEBZ 'SJEBZ Appointments (B[FUUF (PPE'SJEBZ BOE Pther HB[FUUF SFMFBTFE 1VCMJD)PMJEBZ Ootices UPCFTVCNJUUFE PO5IVSTEBZ CZ5VFTEBZ12 noon BGUFSOPPO Final proofs0, UPQVCMJTIUPCF SFDFJWFECZ5VFTEBZ Dlose of business "QSJM Monday 5VFTEBZ8FEOFTEBZ 5IVSTEBZ 'SJEBZ &BTUFS.POEBZ Appointment 0UIFSHB[FUUFOPUJDFT (B[FUUF 1VCMJD)PMJEBZ OPUJDFTUPCF UPCFTVCNJUUFECZ SFMFBTFE TVCNJUUFECZ 8FEOFTEBZOPPO PO'SJEBZ 5VFTEBZ12 noon NPSOJOH 'JOBMQSPPGT0,UP QVCMJTI UPCFSFDFJWFE CZ8FEOFTEBZ DMPTFPGCVTJOFTT Easter Public Holidays [249] Queensland Government Gazette Extraordinary PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ISSN 0155-9370 Vol. 377] Friday 9 March 2018 [No. 44 Transport Operations (Marine Safety) Act 1994 NOTIFICATION OF REVOCATION OF GAZETTE NOTICE Maritime Safety Queensland Cairns I, Captain Michael Barnett, Regional Harbour Master (Cairns), Maritime Safety Queensland, pursuant to the provision of section 206A of the Transport Operations (Marine Safety) Act 1994 hereby revoke the Notification of Speed Limit for the waters of Tinaroo Dam published on page 999 of the Queensland Government Gazette No. 98 dated 25 August 2017. Mariners are reminded of their general safety obligation and urged to navigate with caution at all times. Mariners are to be aware of numerous underwater hazards and the danger of sunken logs and debris in the waters of Tinaroo Dam. Captain Michael Barnett Regional Harbour Master (Cairns) Maritime Safety Queensland Dated: 9th March 2018 © The State of Queensland 2018 Copyright protects this publication. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever means is prohibited without prior written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to: Gazette Advertising, GPO Box 2457, Brisbane QLD 4001. -

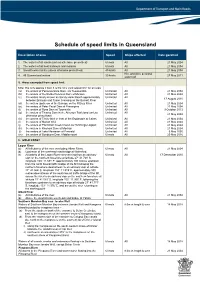

Schedule of Speed Limits in Queensland

Schedule of speed limits in Queensland Description of area Speed Ships affected Date gazetted 1. The waters of all canals (unless otherwise prescribed) 6 knots All 21 May 2004 2. The waters of all boat harbours and marinas 6 knots All 21 May 2004 3. Smooth water limits (unless otherwise prescribed) 40 knots All 21 May 2004 Hire and drive personal 4. All Queensland waters 30 knots 27 May 2011 watercraft 5. Areas exempted from speed limit Note: this only applies if item 3 is the only valid speed limit for an area (a) the waters of Perserverance Dam, via Toowoomba Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (b) the waters of the Bjelke Peterson Dam at Murgon Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (c) the waters locally known as Sandy Hook Reach approximately Unlimited All 17 August 2010 between Branyan and Tyson Crossing on the Burnett River (d) the waters upstream of the Barrage on the Fitzroy River Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (e) the waters of Peter Faust Dam at Proserpine Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (f) the waters of Ross Dam at Townsville Unlimited All 9 October 2013 (g) the waters of Tinaroo Dam in the Atherton Tableland (unless Unlimited All 21 May 2004 otherwise prescribed) (h) the waters of Trinity Inlet in front of the Esplanade at Cairns Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (i) the waters of Marian Weir Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (j) the waters of Plantation Creek known as Hutchings Lagoon Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (k) the waters in Kinchant Dam at Mackay Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (l) the waters of Lake Maraboon at Emerald Unlimited All 6 May 2005 (m) the waters of Bundoora Dam, Middlemount 6 knots All 20 May 2016 6. -

Broadwater Environmental Values and Water Quality Objectives Basin No

Environmental Protection (Water) Policy 2009 Broadwater environmental values and water quality objectives Basin No. 146 (part), including Biggera and Loders Creeks, the Broadwater and all creeks of the Broadwater catchment and Runaway Bay July 2010 Prepared by: Water Quality & Ecosystem Health Policy Unit Department of Environment and Resource Management © State of Queensland (Department of Environment and Resource Management) 2010 The Department of Environment and Resource Management authorises the reproduction of textual material, whole or part, in any form, provided appropriate acknowledgement is given. This publication is available in alternative formats (including large print and audiotape) on request. Contact (07) 322 48412 or email <[email protected]> July 2010 Document Ref Number Main parts of this document and what they contain • Scope of waters covered Introduction • Key terms / how to use document (section 1) • Links to WQ plan (map) • Mapping / water type information • Further contact details • Amendment provisions • Source of EVs for this document Environmental Values • Table of EVs by waterway (EVs - section 2) - aquatic ecosystem - human use • Any applicable management goals to support EVs • How to establish WQOs to protect Water Quality Objectives all selected EVs (WQOs - section 3) • WQOs in this document, for - aquatic ecosystem EV - human use EVs • List of plans, reports etc containing Ways to improve management actions relevant to the water quality waterways in this area (section 4) • Definitions of key terms including an Dictionary explanation table of all (section 5) environmental values • An accompanying map that shows Accompanying WQ Plan water types, levels of protection and (map) other information contained in this document iii CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ -

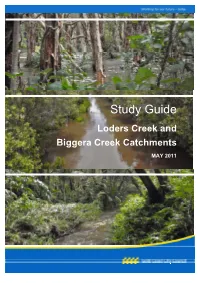

Loders and Biggera Creek Catchment Study Guide

Study Guide Loders Creek and Biggera Creek Catchments MAY 2011 Creek Catchment Study Guide 1 Eastern sedgefrog, Litoria fallax Photo by Narelle Power Loders Creek and Biggera Creek Catchments Study Guide CONTENTS PART A Contents............................................................................................................................................. i Loders Creek and Biggera Creek Catchments ................................................................................. 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 2 What Is a Catchment? ...................................................................................................................... 3 Gold Coast Catchments.................................................................................................................... 4 The Loders and Biggera Creeks Catchments................................................................................... 6 Catchment History ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Loders Creek Catchment......................................................................................................................... 11 loders creek catchment association................................................................................................ 13 Restoring the Catchment........................................................................................................................ -

Legislative Assembly Hansard 1977

Queensland Parliamentary Debates [Hansard] Legislative Assembly TUESDAY, 13 SEPTEMBER 1977 Electronic reproduction of original hardcopy 498 Papers [13 SEPTEMBER 1977] Valuation of Land Act, &c., Bill Secretary, Queensland La:w Society Incorporated, under the Legal Assist ance Act 1965-1975, for the year 1976-77. MINISTERIAL STATEMENT DELEGATION OF AUTHORITY; MINISTER FOR PRIMARY INDUSTRIES Hon. J. BJELKE·PETERSEN (Barambah -Premier) (11.5 a.m.): I desire to inform the House that in connection with the overseas visit of the Minister for Primary Industries, the Deputy Governor, for and on behalf of His Excellency the Governor, by virtue of the provisions of the Officials in Parliament Act 1896--1975, authorised and empowered the Honourable Kooneth Burgoyne Tomkins, M.L.A., Minister for llmds, Forestry, Nat ional Parks and Wtldlife Service, to perform and exercise all or any of the duties, powers and authorities imposed or conferred upon the Minister for Primary Industries by any TUESDAY, 13 SEPTEMBER 1977 Act, rule, practice or ordinance on and from 9 September 1977, and until the return to Queensland of the Honourable Victor Bruce Sullivan, M.L.A. Mr. SPEAKER (Hon. J. E. H. Houghton, I lay upon the table of the House a copy Redcliffe) read prayers and took the chair at 11 a.m. of the Queensland Government Gazette of 10 September 1977 notifying this arrange ment. PAPERS Whereupon the honourable gentleman The following papers were laid on the laid the Queensland Government Gazette on table, and ordered to be printed:- the table. Reports- Commissioner of Land Tax, for the year 1976-77. -

Gold Coast Rapid Transit

Gold Coast Rapid Transit 20 Soils, Geology and Topography 41/16445/364842 Gold Coast Rapid Transit Concept Design Impact Management Plan Volume 2 Chapter 20 - Soils, Geology and Topography Contents 1. Introduction 20–1 2. Description of the Existing Environment 20–2 2.1 Corridor Topography, Landform Patterns and Existing Environment 20–2 2.2 Geology and Soils 20–3 2.3 Contaminated Land 20–15 3. Potential Benefits, Impacts and Mitigation Measures 20–21 3.1 Overview of Potential Benefits and Impacts 20–21 3.2 Specific impacts and mitigation measures 20–22 4. Conclusion and Recommendations 20–27 4.1 Overview 20–27 4.2 Topography and Landform 20–27 4.3 Geology and Soils 20–27 4.4 Acid Sulfate Soils 20–28 4.5 Contaminated Land 20–28 Table Index Table 20-2 Section 3 EMR Listings 20–19 Figure Index Figure 20-1 Topographical and Landform Characteristics of the Study Area (Section 2) 20–5 Figure 20-2 Topographical and Landform Characteristics of the Study Area (Section 3) 20–6 Figure 20-3 Geological Characteristics of the Study Area (Section 2) 20–7 Figure 20-4 Geological Characteristics of the Study Area (Section 3) 20–8 Figure 20-5 Soil Characteristics of the Study Area (Section 2) 20–9 Figure 20-6 Soil Characteristics of the Study Area (Section 3) 20–10 Vol 2 Chp 20–ii 41/16445/364842 Gold Coast Rapid Transit Concept Design Impact Management Plan Volume 2 Chapter 20 - Soils, Geology and Topography Figure 20-7 Acid Sulphate Soils Present within Study Area (Section 2) 20–13 Figure 20-8 Acid Sulphate Soils Present within Study Area (Section 3) 20–14 Figure 20-9 Contaminated Land Present within Study Area (Section 2) 20–16 Figure 20-10 Contaminated Land Present within Study Area (Section 3) 20–17 20 dden heading Vol 2 Chp 20–iii 41/16445/364842 Gold Coast Rapid Transit Concept Design Impact Management Plan Volume 2 Chapter 20 - Soils, Geology and Topography 1. -

Speed Limits Review Discussion Paper May 2014

Speed Limits Review Discussion Paper May 2014 Sustain. Enhance. Promote. Great state. Great opportunity. Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 PRINCIPLES 4 PURPOSE OF THE SPEED LIMITS REVIEW 4 ISSUES AND OPPORTUNITIES 4 Vessel wake & wash 4 Residential disamenity 5 Transportation disamenity 5 Competition & conflict 5 Compliance & enforcement 5 CURRENT SPEED LIMITS 6 Statewide provisions 6 Gold Coast waters gazetted speed limits 6 PREVIOUS PROPOSALS 7 ENFORCEMENT 8 OTHER AUSTRALIAN JURISDICTIONS 9 DISCUSSION OF ISSUES AND OPTIONS 9 RECOMMENDATIONS 12 CONSULTATION 12 REFERENCES 13 Appendix A – Restrictions in other jurisdictions 14 Speed Limits Review 2 | Gold Coast Waterways Authority Speed Limits Review 2 Abbreviations GCWA Gold Coast Waterways Authority MIN Marine Infringement Notice MSQ Maritime Safety Queensland NSW New South Wales PWC Personal water craft QBFP Queensland Boating and Fisheries Patrol QPS Queensland Police Service SA South Australia TOMSA Transport Operations (Marine Safety) Act TMR Department of Transport and Main Roads VIC Victoria Speed Limits Review Gold Coast Waterways Authority Speed Limits Review | 3 3 approach has not been implemented, in part due to the lack of consensus regarding an Principles enforceable definition. The following principles are suggested as the basis for future decision making, both with Residential disamenity respect to the recommendations below and in reference to ad hoc speed and behaviour issues that may arise in the future. Along with wash effects, noise is the most common concern expressed by waterside residents. Noise will generally increase with speed for a given vessel, but the difference Deliver the best possible management of the Gold Coast waterways between vessels/power sources is potentially more significant. -

South East Queensland the Blue Tiger Migration

South East Queensland APRIL 2015 Volume 9 Number 2 Newsletter of the Land for Wildlife Program South East Queensland ISSN 1835-3851 CONTENTS 1 The Blue Tiger Migration 2 Editorial and contacts 3 Fauna Vignette It’s a Pademelon 4 Pest Management To Bait or not to Bait 5 Pest Management What’s Killing our Birds? 6 Pest Management The Blue Tiger Migration A Surprising Encounter t was difficult to miss the Blue Tiger not to the Blue Tiger larvae. When the 7 My little corner Imigration through SEQ earlier this year. It larvae eat Corky Milk Vine, the poisonous Discovery of a Chain made the news and went where few insect chemicals get passed on to the pupae and Ribbon Orchid stories go, into social media and general adult butterflies. These toxins then work to public chit-chat. But where are they now protect adult Blue Tigers from being eaten 8-9 Practicalities and what were they doing here? by birds, as birds have learnt that they get Surveying Freshwater Fish sick from ingesting Blue Tigers. Blue Tigers are mostly a tropical butterfly and can be seen nearly all year round in When cooler weather arrives, Blue Tigers 9 Glossy Black Cockatoo North Queensland. They are migratory will head back north passing through Birding Day and fly south during spring and summer southern Queensland in April and May. reaching southern Queensland, NSW and They are known to congregate in huge 10-11 Practicalities even Victoria. Huge numbers, probably numbers over winter, clustering on stems Need some leverage with your in the hundreds of thousands, were seen and vines in sheltered gullies in central and weed control? widely across SEQ from November 2014 north Queensland. -

Speed and Behaviour Management Strategy Consultation Report

Speed and Behaviour Management Strategy Consultation Report December 2016 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT 5 Speed and Behaviour Management Strategy 5 Australian Maritime College Report 5 Survey 5 Interactive map 6 Advertisements and outlets 7 Response demographics 7 RESPONSE TO KEY THEMES 8 Introduction 9 Speed limit zones 10 Vessel wake and wash 13 Broadwater – Two-channel strategy 15 Managing the impacts of changes to the Yellow zone 18 “Grandfathering” allowance 18 Commercial allowance 19 “Water-skiing” allowance 19 Managing activities designed to enhance wash 21 Coomera River and Coombabah Creek 23 Nerang River 23 Nerang River – Water skiing 24 Clear Island Waters 26 Moreton Bay Marine Park changes 26 Appendix A – Speed and Behaviour Management Strategy A-1 Appendix B – Emailed invitations and reminders B-1 Appendix C – Survey results C-1 Appendix D – Survey comments D-1 Appendix E – Additional comments (email, post) E-1 Speed and Behaviour – Consultation Report 2 Abbreviations AMC Australian Maritime College (University of Tasmania) GCWA Gold Coast Waterways Authority MP(s) Member of Parliament (Queensland) MSQ Maritime Safety Queensland PWC Personal water craft QBFP Queensland Boating and Fisheries Patrol QPS Queensland Police Service SBMS Speed and Behaviour Management Strategy (also “Strategy”) TOMSA Transport Operations (Marine Safety) Act TMR Department of Transport and Main Roads Speed and Behaviour – Consultation Report 3 Executive Summary This report documents the public response to GCWA’s invitation to provide comments on the draft Speed and Behaviour Management Strategy. The Strategy was prepared in response to the Speed Limits Review consultation undertaken in 2014. Accordingly, it’s not surprising that many of the views represented here reflect those put forward in 2014, whether in agreement with components of the Strategy or offering alternatives considered in preparing the Strategy.