Detection of an Airflow System in Niedzwiedzia (Bear) Cave, Kletno, Poland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

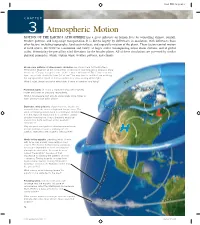

3 Atmospheric Motion

Final PDF to printer CHAPTER 3 Atmospheric Motion MOTION OF THE EARTH’S ATMOSPHERE has a great influence on human lives by controlling climate, rainfall, weather patterns, and long-range transportation. It is driven largely by differences in insolation, with influences from other factors, including topography, land-sea interfaces, and especially rotation of the planet. These factors control motion at local scales, like between a mountain and valley, at larger scales encompassing major storm systems, and at global scales, determining the prevailing wind directions for the broader planet. All of these circulations are governed by similar physical principles, which explain wind, weather patterns, and climate. Broad-scale patterns of atmospheric circulation are shown here for the Northern Hemisphere. Examine all the components on this figure and think about what you know about each. Do you recognize some of the features and names? Two features on this figure are identified with the term “jet stream.” You may have heard this term watching the nightly weather report or from a captain on a cross-country airline flight. What is a jet stream and what effect does it have on weather and flying? Prominent labels of H and L represent areas with relatively higher and lower air pressure, respectively. What is air pressure and why do some areas have higher or lower pressure than other areas? Distinctive wind patterns, shown by white arrows, are associated with the areas of high and low pressure. The winds are flowing outward and in a clockwise direction from the high, but inward and in a counterclockwise direction from the low. -

Climate and Atmospheric Circulation of Mars

Climate and QuickTime™ and a YUV420 codec decompressor are needed to see this picture. Atmospheric Circulation of Mars: Introduction and Context Peter L Read Atmospheric, Oceanic & Planetary Physics, University of Oxford Motivating questions • Overview and phenomenology – Planetary parameters and ‘geography’ of Mars – Zonal mean circulations as a function of season – CO2 condensation cycle • Form and style of Martian atmospheric circulation? • Key processes affecting Martian climate? • The Martian climate and circulation in context…..comparative planetary circulation regimes? Books? • D. G. Andrews - Intro….. • J. T. Houghton - The Physics of Atmospheres (CUP) ALSO • I. N. James - Introduction to Circulating Atmospheres (CUP) • P. L. Read & S. R. Lewis - The Martian Climate Revisited (Springer-Praxis) Ground-based observations Percival Lowell Lowell Observatory (Arizona) [Image source: Wikimedia Commons] Mars from Hubble Space Telescope Mars Pathfinder (1997) Mars Exploration Rovers (2004) Orbiting spacecraft: Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (NASA) Image credits: NASA/JPL/Caltech Mars Express orbiter (ESA) • Stereo imaging • Infrared sounding/mapping • UV/visible/radio occultation • Subsurface radar • Magnetic field and particle environment MGS/TES Atmospheric mapping From: Smith et al. (2000) J. Geophys. Res., 106, 23929 DATA ASSIMILATION Spacecraft Retrieved atmospheric parameters ( p,T,dust...) - incomplete coverage - noisy data..... Assimilation algorithm Global 3D analysis - sequential estimation - global coverage - 4Dvar .....? - continuous in time - all variables...... General Circulation Model - continuous 3D simulation - complete self-consistent Physics - all variables........ - time-dependent circulation LMD-Oxford/OU-IAA European Mars Climate model • Global numerical model of Martian atmospheric circulation (cf Met Office, NCEP, ECMWF…) • High resolution dynamics – Typically T31 (3.75o x 3.75o) – Most recently up to T170 (512 x 256) – 32 vertical levels stretched to ~120 km alt. -

History of Frontal Concepts Tn Meteorology

HISTORY OF FRONTAL CONCEPTS TN METEOROLOGY: THE ACCEPTANCE OF THE NORWEGIAN THEORY by Gardner Perry III Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June, 1961 Signature of'Author . ~ . ........ Department of Humangties, May 17, 1959 Certified by . v/ .-- '-- -T * ~ . ..... Thesis Supervisor Accepted by Chairman0 0 e 0 o mmite0 0 Chairman, Departmental Committee on Theses II ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The research for and the development of this thesis could not have been nearly as complete as it is without the assistance of innumerable persons; to any that I may have momentarily forgotten, my sincerest apologies. Conversations with Professors Giorgio de Santilw lana and Huston Smith provided many helpful and stimulat- ing thoughts. Professor Frederick Sanders injected thought pro- voking and clarifying comments at precisely the correct moments. This contribution has proven invaluable. The personnel of the following libraries were most cooperative with my many requests for assistance: Human- ities Library (M.I.T.), Science Library (M.I.T.), Engineer- ing Library (M.I.T.), Gordon MacKay Library (Harvard), and the Weather Bureau Library (Suitland, Md.). Also, the American Meteorological Society and Mr. David Ludlum were helpful in suggesting sources of material. In getting through the myriad of minor technical details Professor Roy Lamson and Mrs. Blender were indis-. pensable. And finally, whatever typing that I could not find time to do my wife, Mary, has willingly done. ABSTRACT The frontal concept, as developed by the Norwegian Meteorologists, is the foundation of modern synoptic mete- orology. The Norwegian theory, when presented, was rapidly accepted by the world's meteorologists, even though its several precursors had been rejected or Ignored. -

Ocean Circulation and Climate: a 21St Century Perspective

Chapter 13 Western Boundary Currents Shiro Imawaki*, Amy S. Bower{, Lisa Beal{ and Bo Qiu} *Japan Agency for Marine–Earth Science and Technology, Yokohama, Japan {Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, Massachusetts, USA {Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami, Miami, Florida, USA }School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA Chapter Outline 1. General Features 305 4.1.3. Velocity and Transport 317 1.1. Introduction 305 4.1.4. Separation from the Western Boundary 317 1.2. Wind-Driven and Thermohaline Circulations 306 4.1.5. WBC Extension 319 1.3. Transport 306 4.1.6. Air–Sea Interaction and Implications 1.4. Variability 306 for Climate 319 1.5. Structure of WBCs 306 4.2. Agulhas Current 320 1.6. Air–Sea Fluxes 308 4.2.1. Introduction 320 1.7. Observations 309 4.2.2. Origins and Source Waters 320 1.8. WBCs of Individual Ocean Basins 309 4.2.3. Velocity and Vorticity Structure 320 2. North Atlantic 309 4.2.4. Separation, Retroflection, and Leakage 322 2.1. Introduction 309 4.2.5. WBC Extension 322 2.2. Florida Current 310 4.2.6. Air–Sea Interaction 323 2.3. Gulf Stream Separation 311 4.2.7. Implications for Climate 323 2.4. Gulf Stream Extension 311 5. North Pacific 323 2.5. Air–Sea Interaction 313 5.1. Upstream Kuroshio 323 2.6. North Atlantic Current 314 5.2. Kuroshio South of Japan 325 3. South Atlantic 315 5.3. Kuroshio Extension 325 3.1. -

Lecture 6 Winds: Atmosphere and Ocean Circulation

Lecture 6 Winds: Atmosphere and Ocean Circulation The global atmospheric circulation and its seasonal variability is driven by the uneven solar heating of the Earth’s atmosphere and surface. Solar radiation on a planet at different axial inclinations. The concept of flux density (1/d2, energy/time/area) and the cosine law. Because Earth’s rotation axis is tilted relative to the plane of its orbit around the sun, there is seasonal variability in the geographical distribution of sunshine March 21, vernal equinox December 21, winter solstice June 21, summer solstice September 23, autumnal equinox Zonally averaged components of the annual mean absorbed solar flux, emitted Earth’s infrared flux, and net radiative flux at the top of the atmosphere, derived from satellite observations. + _ _ The geographical distribution of temperature and its seasonal variability closely follows the geographical distribution of sunshine (solar radiation). Temperature plays a direct role in determining the climate of every region. Temperature differences are also key in driving the global atmospheric circulation. Warm air tends to rise because it is light, while cold air tends to sink because it is dense, this sets the atmosphere in motion. The tropical circulation is a good example of this. In addition to understanding how temperature affects the atmospheric circulation, we also need to understand one of the basic forces governing air and water motion on earth: The Coriolis Force. But to understand this effect, we first need to review the concept of angular momentum conservation. Angular momentum conservation means that if a rotating object moves closer to its axis of rotation, it must speed up to conserve angular momentum. -

CHAPTER 3 Transport and Dispersion of Air Pollution

CHAPTER 3 Transport and Dispersion of Air Pollution Lesson Goal Demonstrate an understanding of the meteorological factors that influence wind and turbulence, the relationship of air current stability, and the effect of each of these factors on air pollution transport and dispersion; understand the role of topography and its influence on air pollution, by successfully completing the review questions at the end of the chapter. Lesson Objectives 1. Describe the various methods of air pollution transport and dispersion. 2. Explain how dispersion modeling is used in Air Quality Management (AQM). 3. Identify the four major meteorological factors that affect pollution dispersion. 4. Identify three types of atmospheric stability. 5. Distinguish between two types of turbulence and indicate the cause of each. 6. Identify the four types of topographical features that commonly affect pollutant dispersion. Recommended Reading: Godish, Thad, “The Atmosphere,” “Atmospheric Pollutants,” “Dispersion,” and “Atmospheric Effects,” Air Quality, 3rd Edition, New York: Lewis, 1997, pp. 1-22, 23-70, 71-92, and 93-136. Transport and Dispersion of Air Pollution References Bowne, N.E., “Atmospheric Dispersion,” S. Calvert and H. Englund (Eds.), Handbook of Air Pollution Technology, New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1984, pp. 859-893. Briggs, G.A. Plume Rise, Washington, D.C.: AEC Critical Review Series, 1969. Byers, H.R., General Meteorology, New York: McGraw-Hill Publishers, 1956. Dobbins, R.A., Atmospheric Motion and Air Pollution, New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1979. Donn, W.L., Meteorology, New York: McGraw-Hill Publishers, 1975. Godish, Thad, Air Quality, New York: Academic Press, 1997, p. 72. Hewson, E. Wendell, “Meteorological Measurements,” A.C. -

Synoptic Meteorology

Lecture Notes on Synoptic Meteorology For Integrated Meteorological Training Course By Dr. Prakash Khare Scientist E India Meteorological Department Meteorological Training Institute Pashan,Pune-8 186 IMTC SYLLABUS OF SYNOPTIC METEOROLOGY (FOR DIRECT RECRUITED S.A’S OF IMD) Theory (25 Periods) ❖ Scales of weather systems; Network of Observatories; Surface, upper air; special observations (satellite, radar, aircraft etc.); analysis of fields of meteorological elements on synoptic charts; Vertical time / cross sections and their analysis. ❖ Wind and pressure analysis: Isobars on level surface and contours on constant pressure surface. Isotherms, thickness field; examples of geostrophic, gradient and thermal winds: slope of pressure system, streamline and Isotachs analysis. ❖ Western disturbance and its structure and associated weather, Waves in mid-latitude westerlies. ❖ Thunderstorm and severe local storm, synoptic conditions favourable for thunderstorm, concepts of triggering mechanism, conditional instability; Norwesters, dust storm, hail storm. Squall, tornado, microburst/cloudburst, landslide. ❖ Indian summer monsoon; S.W. Monsoon onset: semi permanent systems, Active and break monsoon, Monsoon depressions: MTC; Offshore troughs/vortices. Influence of extra tropical troughs and typhoons in northwest Pacific; withdrawal of S.W. Monsoon, Northeast monsoon, ❖ Tropical Cyclone: Life cycle, vertical and horizontal structure of TC, Its movement and intensification. Weather associated with TC. Easterly wave and its structure and associated weather. ❖ Jet Streams – WMO definition of Jet stream, different jet streams around the globe, Jet streams and weather ❖ Meso-scale meteorology, sea and land breezes, mountain/valley winds, mountain wave. ❖ Short range weather forecasting (Elementary ideas only); persistence, climatology and steering methods, movement and development of synoptic scale systems; Analogue techniques- prediction of individual weather elements, visibility, surface and upper level winds, convective phenomena. -

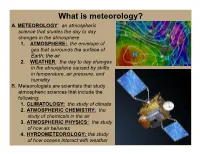

5-6 Meteorology Notes

What is meteorology? A. METEOROLOGY: an atmospheric science that studies the day to day changes in the atmosphere 1. ATMOSPHERE: the envelope of gas that surrounds the surface of Earth; the air 2. WEATHER: the day to day changes in the atmosphere caused by shifts in temperature, air pressure, and humidity B. Meteorologists are scientists that study atmospheric sciences that include the following: 1. CLIMATOLOGY: the study of climate 2. ATMOSPHERIC CHEMISTRY: the study of chemicals in the air 3. ATMOSPHERIC PHYSICS: the study of how air behaves 4. HYRDOMETEOROLOGY: the study of how oceans interact with weather What is the atmosphere? A. The earth’s atmosphere is made of air. 1. Air is a mixture of matter that includes the following: a. 78% nitrogen gas b. 21% oxygen gas c. 0.04% carbon dioxide d. 0.96% other components like water vapor, dust, smoke, salt, methane, etc. 2. The atmosphere goes from the Earth’s surface to 700km up. 3. The atmosphere is divided into 4 main layers as one ascends. What is the atmosphere? a. TROPOSPHERE: contains most air, where most weather occurs, starts at sea level b. STRATOSPHERE: contains the ozone layer that holds back some UV radiation c. MESOSPHERE: slows and burns up meteoroids d. THERMOSPHERE: absorbs some energy from the sun What is the atmosphere? B. The concentration of air in the atmosphere increases the closer one gets to sea level. 1. The planet’s gravity pulls the atmosphere against the surface. 2. Air above pushes down on air below, causing a higher concentration in the troposphere. -

ICA Vol. 1 (1956 Edition)

·wMo o '-" I q Sb 10 c. v. i. J c.. A INTERNATIONAL CLOUD ATLAS Volume I WORLD METEOROLOGICAL ORGANIZATION 1956 c....._/ O,-/ - 1~ L ) I TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages Preface to the 1939 edition . IX Preface to the present edition . xv PART I - CLOUDS CHAPTER I Introduction 1. Definition of a cloud . 3 2. Appearance of clouds . 3 (1) Luminance . 3 (2) Colour .... 4 3. Classification of clouds 5 (1) Genera . 5 (2) Species . 5 (3) Varieties . 5 ( 4) Supplementary features and accessory clouds 6 (5) Mother-clouds . 6 4. Table of classification of clouds . 7 5. Table of abbreviations and symbols of clouds . 8 CHAPTER II Definitions I. Some useful concepts . 9 (1) Height, altitude, vertical extent 9 (2) Etages .... .... 9 2. Observational conditions to which definitions of clouds apply. 10 3. Definitions of clouds 10 (1) Genera . 10 (2) Species . 11 (3) Varieties 14 (4) Supplementary features and accessory clouds 16 CHAPTER III Descriptions of clouds 1. Cirrus . .. 19 2. Cirrocumulus . 21 3. Cirrostratus 23 4. Altocumulus . 25 5. Altostratus . 28 6. Nimbostratus . 30 " IV TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages 7. Stratoculllulus 32 8. Stratus 35 9. Culllulus . 37 10. Culllulonimbus 40 CHAPTER IV Orographic influences 1. Occurrence, structure and shapes of orographic clouds . 43 2. Changes in the shape and structure of clouds due to orographic influences 44 CHAPTER V Clouds as seen from aircraft 1. Special problellls involved . 45 (1) Differences between the observation of clouds frolll aircraft and frolll the earth's surface . 45 (2) Field of vision . 45 (3) Appearance of clouds. 45 (4) Icing . -

On Coriolis and the Deflective Force

C. L. Jordan on Coriolis and the Florida State University deflective force Tallahassee, Fla. Coriolis force or deflective force of the Encyclopedia Britannica published in 1922 does Now every meteorology student soon encounters the not carry an item on Coriolis or coriolis force. Begin- name Coriolis in association with the apparent deflective ning around 1930, practically every physics text which force due to the earth's rotation. This association is, how- discusses the influence of the earth's rotation on moving ever, a relatively recent innovation since Coriolis was objects refers to the coriolis force or acceleration. given little recognition by meteorologists for about 100 years following the publication of his 1835 paper deal- Recognition given Coriolis in the 1880-1930 period ing with accelerations in relative coordinate systems The lack of recognition of Coriolis by meteorologists (Coriolis, 1835). In the United States and Great Britain, may have been due to a complete ignorance of his work the terms deflective force and deviating force (of the within some groups and, among others, to a lack of ap- earth's rotation) were in general use until about 1940. preciation of the general applicability of the ideas pre- Widely used texts in the 1930's, such as Brunt (1934) and sented in his 1835 paper. Several references to Coriolis Humphreys (1928), make no reference to Coriolis or to have been noted during the 1880-1930 period (cf. the coriolis force and these items do not appear in the Sprung, 1881; Gunter, 1899; Ekman, 1905; Shaw, 1926) third edition of the Meteorological Glossary (Meteoro- but none of these refer to the deflective force as the logical Office, 1940). -

Introduction to Synoptic Meteorology Введение В

Ministry of Science and Education of the Russian Federation RUSSIAN STATE HUDROMETEOROLOGICAL UNIVERSITY V.I. Vorobyev, G.G. Tarakanov INTRODUCTION TO SYNOPTIC METEOROLOGY ВВЕДЕНИЕ В СИНОПТИЧЕСКУЮ МЕТЕОРОЛОГИЮ Рекомендовано Учебно-методическим объединением по образованию в области гидрометеорологии в качестве учебного пособия для студентов высших учебных заведений, обучающихся по направлению «Гидрометеорология» RSHCJ Se. Petersburg 2005 UDK 551.509.32 (0758) Vorobyev V. I., Tarakanov G. G. Introduction to synoptic meteorology. Manuel. СПб. Изд. РГГМУ, 2005 - 40 pp. ISBN 5-86813-160-9 The book considers the major concepts and terms that students of hydrometeorology are to know while taking the basic course of synoptic meteorology. The aim of the manual is the deeper comprehension of the content of the course. The manual is intended for students of higher educational institu tions specializing in hydrometeorology. It can be also useful for geogra phers and specialists whose work requires account for weather. ISBN 5-86813-160-9 © Vorobyev V.I., Tarakanov G.G., 2005 © Russian State Hydrometeorological University (RSHU), 2005 Российский государственный гидроммворилогический университет би бл и о тека INTRODUCTION TO SYNOPTIC METEOROLOGY Foreword Variation of weather in a region is closely associated with so called synoptic objects acting in the region or passing it. Study of these objects and the associated weather conditions represents the main content of the discipline called synoptic meteorology. All synoptic objects are closely related to each other. Therefore, when studying a synoptic object, un avoidably reference to some other objects should be made. It is why, be fore one starts systematic studying synoptic meteorology, it is worth be ing, at least briefly, familiarized with basic notions and definitions re lated to the processes of origination and evolution of the synoptic ob jects, and with some special features of the meteorological fields struc ture within the limit of every object. -

5Th Grade Weather Unit Northside Outdoor Wonder & Learning Initiative

5th Grade Earth Science: Weather Unit Cover photo credit: Lauren Greene Developed for Chapel Hill Carrboro City Schools Northside Elementary School Outdoor Wonder & Learning (OWL) Initiative Unless otherwise noted, activities written by: Toni Stadelman, Dana Haine, Lauren Greene, & Sarah Yelton Center for Public Engagement with Science UNC Institute for the Environment In collaboration with 5th grade teachers at Northside Elementary School: Michelle Gay, Daila Patrick, & Elizabeth Symons ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to Dan Schnitzer, Coretta Sharpless, Kirtisha Jones and the many wonderful teachers and support staff at Northside Elementary for their participation in and support of the Northside OWL Initiative. Thanks to Chip Konrad, UNC Professor and Director of the South East Regional Climate Center for sharing his time and resources during the development of this unit. Thanks also to Shelby Brown for her invaluable assistance compiling, editing, and proofreading the curriculum. Instructional materials and supplies to promote STEM-based outdoor learning were instrumental to the successful implementation of this curriculum. The purchase of these materials was made possible with funding provided by the Duke Energy Foundation to Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools. Curriculum developed June 2018 – July 2019 For more information, contact: Sarah Yelton, Environmental Education & Citizen Science Program Manager UNC Institute for the Environment Center for Public Engagement with Science [email protected] 5th Grade Weather Unit Northside Outdoor Wonder & Learning Initiative th 5 Grade Weather Unit Overarching Unit Question What is weather and how does it affect us? Essential Questions Arc 1: What is weather and what factors influence the weather? Arc 2: How does the ocean affect our weather? Arc 3: How does weather affect our lives? Transfer Goals o Use scientific thinking to understand the relationships and complexities of the world around them.