Top Gear and Anti-Environmentalism AS Jan16.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

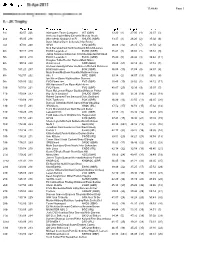

Relay Results

11:48:48 Page 1 1st 92:57 226 Interlopers Team Compass INT (GBR) 33:20 (1) 27:00 (4) 32:37 (3) Anthony Squire/Oleg Chepelin/Murray Strain 2nd 95:05 236 Who needs Graham? or R SHUOC (GBR) 33:37 (3) 26:26 (2) 35:02 (6) Dave Adams/Dave Schorah/John Rocke 3rd 97:03 240 SYO1 SYO (GBR) 36:28 (12) 28:37 (7) 31:58 (2) Nick Barrable/Neil Northrop/David Brickhill-Jones 4th 97:17 219 EUOC Legends 2 EUOC (GBR) 35:41 (7) 26:03 (1) 35:33 (9) Jamie Stevenson/Duncan Coombs/Alasdair Mcclead 5th 99:13 218 EUOC Legends 1 EUOC (GBR) 35:49 (8) 26:42 (3) 36:42 (11) Douglas Tullie/Hector Haines/Mark Nixon 6th 99:14 230 Robin Hood NOC (GBR) 39:48 (21) 28:14 (6) 31:12 (1) Andrew Llewellyn/Peter Hodkinson/Richard Robinson 7th 101:21 207 BOK Hurricanes BOK (GBR) 36:05 (10) 31:09 (8) 34:07 (4) Mark Bown/Matthew Franklin/Matthew Crane 8th 102:57 202 Aire 1 AIRE (GBR) 33:34 (2) 34:07 (13) 35:16 (8) Ian Nixon/Steve Watkins/Ben Stevens 9th 105:00 222 FVO Flyers too FVO (GBR) 38:46 (19) 28:02 (5) 38:12 (17) Will Hensman/Tom Ryan/Kyle Heron 10th 107:53 221 FVO Flyers FVO (GBR) 40:07 (25) 32:39 (9) 35:07 (7) Ross McLennan/Roger Goddard/Marcus Pinker 11th 110:04 237 Big city in England SHUOC (GBR) 36:03 (9) 35:39 (18) 38:22 (18) Robert Gardner/Tom Beasant/Chris Smithard 12th 110:09 208 BOK Typhoons BOK (GBR) 36:39 (13) 32:55 (11) 40:35 (20) Duncan Girtwistle/Keith Agmen/Huw Stradling 13th 110:17 201 3ROCkets 3ROC (IRL) 37:52 (17) 34:53 (15) 37:32 (14) Colm Moran/Andrew Quin/Gerard Butler 14th 110:29 245 Lakeland OC LOC (GBR) 34:18 (4) 33:42 (12) 42:29 (24) Todd Oates/Jack -

Mandy Tranter CV 2018

MANDY TRANTER 07773 421 913 // [email protected] // LINKEDIN.COM/IN/MANDYTRANTER BROADCAST PROFILE Our Guy in China I am a freelance Editor with 17 years experience of working in broadcast television. The Gadget Show My Kitchen Rules UK My creativity and technical knowledge have enabled me to pursue an exciting career. Having been employed as a staff editor for 6 years I decided to become a Do You Know? freelance offline editor and now enjoy working on a wide range of programmes. The Jury Room My editor credits include Our Guy In China (CH4), The Gadget Show (Channel 5), Operation Ouch Fifth Gear (Discovery), My Kitchen Rules UK (CH4), The Street That Cut Everything (BBC1) and the Royal Shakespeare Company for cinema broadcast features on Garden Rescue King Lear, Cymbeline & Henry V. The Instant Gardener Guy Martin's Spitfire WORK House That 100K Built OFFLINE EDITOR // ROYAL SHAKESPEARE COMPANY // 2018 Give A Pet A Home NATIONWIDE CINEMA BROADCAST FEATURES FOR TWELFTH NIGHT Fifth Gear The Street That Cut Everything OFFLINE EDITOR // DAISYBECK STUDIOS // 2017 I Didn’t Know That HARROGATE: A GREAT YORKSHIRE CHRISTMAS (Channel 5) Speed With Guy Martin OFFLINE EDITOR // 7 WONDER // 2017 How Britain Worked MY KITCHEN RULES UK, SERIES 2 (CH4) Big Strong Boys Star Portraits OFFLINE EDITOR // 7 WONDER // 2017 Soul Boy (RTS Award Winner) DO YOU KNOW?, SERIES 2 (CBeebies) Everything Must Go OFFLINE EDITOR // First Look TV // 2017 Points Of View THE JURY ROOM (CBS Reality) EXPERTISE OFFLINE EDITOR // NORTH ONE TV // 2016 Avid Media Composer OUR -

Second Strike Gearing Calculator

Second Strike October 31 and December 31, 2002 The Newsletter for the Superformance Owners Group Page 1 SECOND STRIKE GEARING CALCULATOR The Second Strike Gearing Calculator Transmission Mk III Coupe GT Ford Toploader Yes 4-speed (close ratio) Ford Toploader Yes 4-speed (wide ratio) RBT 5-speed Yes (transaxle) Rear Axle Ratio BTR Rear Axle Ford 8.8 RBT Coupe Ratio Mk III GT Mk III 3.08 Yes 3.27 Yes 3.46 Yes 3.55 Yes 3.73 Yes 3.77 Yes 3.91 Yes 4.10 Yes 4.30 Yes 4.56 Yes The Ford 8.8 IRS (independent rear suspension) rear end is used in MK III’s prior to chassis number 2068. The BTR is To assist owners in evaluating transmission, rear end ratio, and used in the Mk III from chassis 2068 on. tire combinations, an interactive gearing calculator has been added to the Second Strike web site (www.SecondStrike.com). Tire Size Mk III Coupe GT The calculator is designed to help you analyze contemplated Common 275/60-15 285/50-18 275/60-15 changes and get it right before committing your hard earned Tire Sizes 295/50-15 295/45-18 295/50-15 bucks. Changing the transmission, rear end, or rim size is not 335/35-17 315/35-18 for the faint of heart or thin of wallet. The “standard” tire size is shown first. Other commonly used Input Section sizes are also shown. The Gearing Calculator supports the most commonly used transmissions, rear ends and tire sizes used for the 275/60-15 is a 275 width, 60 aspect ratio, and 15” rim Superformance Mk III, Coupe, and GT. -

Pressreader Magazine Titles

PRESSREADER: UK MAGAZINE TITLES www.edinburgh.gov.uk/pressreader Computers & Technology Sport & Fitness Arts & Crafts Motoring Android Advisor 220 Triathlon Magazine Amateur Photographer Autocar 110% Gaming Athletics Weekly Cardmaking & Papercraft Auto Express 3D World Bike Cross Stitch Crazy Autosport Computer Active Bikes etc Cross Stitch Gold BBC Top Gear Magazine Computer Arts Bow International Cross Stitcher Car Computer Music Boxing News Digital Camera World Car Mechanics Computer Shopper Carve Digital SLR Photography Classic & Sports Car Custom PC Classic Dirt Bike Digital Photographer Classic Bike Edge Classic Trial Love Knitting for Baby Classic Car weekly iCreate Cycling Plus Love Patchwork & Quilting Classic Cars Imagine FX Cycling Weekly Mollie Makes Classic Ford iPad & Phone User Cyclist N-Photo Classics Monthly Linux Format Four Four Two Papercraft Inspirations Classic Trial Mac Format Golf Monthly Photo Plus Classic Motorcycle Mechanics Mac Life Golf World Practical Photography Classic Racer Macworld Health & Fitness Simply Crochet Evo Maximum PC Horse & Hound Simply Knitting F1 Racing Net Magazine Late Tackle Football Magazine Simply Sewing Fast Bikes PC Advisor Match of the Day The Knitter Fast Car PC Gamer Men’s Health The Simple Things Fast Ford PC Pro Motorcycle Sport & Leisure Today’s Quilter Japanese Performance PlayStation Official Magazine Motor Sport News Wallpaper Land Rover Monthly Retro Gamer Mountain Biking UK World of Cross Stitching MCN Stuff ProCycling Mini Magazine T3 Rugby World More Bikes Tech Advisor -

IN the RING TAXI Sabine Schmitz Treats Dieter Losskarn to the Most Intense Ten Minutes of His Life

78 CAR CULTURE ❘ THE RING QUEEN 79 11 TO TAKE A RIDE: IN THE RING TAXI Sabine Schmitz treats Dieter Losskarn to the most intense ten minutes of his life. The Ring Queen and her hell-toy, a BMW M5,reigns supreme Just as well Dieter didn’t have time for PHOTOGRAPHY: WAlTeR MathiAs Wilbert & DieTeR LosskARn breakfast. Sabine’s warm-up lap is lightning quick Sabine in action Imagine A wOman TODAY BMW STANDS for ‘Breakfast Must Sabine’s current Nordschleife lap count is public one-way road. Yes, public. The 20.8km Wait’. If you intend to join Sabine Schmitz about 24 000, nearly 1 200 laps a year. Her Nurburgring is part of Germany’s road system. The famous Top Gear video, where she around the 73 corners of the world’s most mantra: ‘Everybody can drive fast on the In case of an accident (several during public throws a Ford Transit around the ring in record time: who cAusEs yOuR famous racetrack, she recommends that you autobahn, but drifting sideways at 140kph on days), the police will file a report. Your car has www.youtube.com/watch?v=m1pklvKKnd0 don’t have breakfast before you climb into the the ring is completely different.’ to be street legal to enter the ring, but otherwise The Stig vs Sabine Schmitz: passenger seat of her BMW M5 ring taxi. In 2004 she added to her fame count when anything on wheels can (and does) go. www.youtube.com/ pAlms to sweat With a V10 under the hood and 378kW it is she challenged Jeremy Clarkson of Top Gear, From superbikes to sightseeing buses, with watch?v=Q1p0Gg9uLBw&NR=1 definitely the most powerful taxi available for claiming she could beat his lap time of 9min GTRs, GT3s and AMGs thrown in, it’s a Sabine in the BMW Ring Taxi: hire in the world and Sabine is the fastest hack. -

Who Wants to Be a Millionaire Host on 'Worst Year'

7 Ts&Cs apply Iceland give huge discount Claire King health: Craig Revel Horwood Kate Middleton pregnant Jenny Ryan: ‘The cat is out to emergency service Emmerdale star's health: ‘It was getting with twins on royal tour in the bag’ The Chase quizzer workers - find… diagnosis ‘I was worse’ Strictly… Pakistan?… announces… Jeremy Clarkson: ‘Wanted to top myself’ Who Wants To Be A Millionaire host on 'worst year' JEREMY CLARKSON - who fronts ITV show Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? - shared his thoughts on a recent study which claimed 1978 was the “worst year” in British history. Who Wants to Be a Millionaire: Jeremy criticises the contestant Earlier this week, researchers from Warwick University claimed people of Britain were at their most unhappy in 1978. The latter year and the first two months of 1979 are best remembered for the Winter of Discontent, where strikes took place and caused various disruptions. ADVERTISING 1/6 Jeremy Clarkson (/search?s=jeremy+clarkson) shared his thoughts on the study as he recalled his first year of working during the strikes. PROMOTED STORY 4x4 Magazine: the SsangYong Musso is a quantum leap forward (SsangYong UK)(https://www.ssangyonggb.co.uk/press/first-drive-ssangyong-musso/56483&utm-source=outbrain&utm- medium=musso&utm-campaign=native&utm-content=4x4-magazine?obOrigUrl=true) In his column with The Sun newspaper, he wrote: “It’s been claimed that 1978 was the worst year in British history. RELATED ARTICLES Jeremy Clarkson sports slimmer waistline with girlfriend Lisa Jeremy Clarkson: Who Wants To Be A Millionaire host on his Hogan weight loss (/celebrity-news/1191860/Jeremy-Clarkson-weight-loss-girlfriend- (/celebrity-news/1192773/Jeremy-Clarkson-weight-loss-health- Lisa-Hogan-pictures-The-Grand-Tour-latest-news) Who-Wants-To-Be-A-Millionaire-age-ITV-Twitter-news) “I was going to argue with this. -

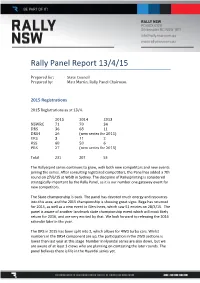

Rally Panel Report 13/4/15

Rally Panel Report 13/4/15 Prepared for: State Council Prepared by: Matt Martin, Rally Panel Chairman. 2015 Registrations 2015 Registrations as at 13/4. 2015 2014 2013 NSWRC 71 70 34 DRS 36 68 11 DRS4 26 (new series for 2015) ERS 3 11 2 RSS 68 58 6 PRS 27 (new series for 2015) Total 231 207 53 The Rallysrpint series continues to grow, with both new competitors and new events joining the series. After consulting registered competitors, the Panel has added a 7th round on 27/6/15 at WSID in Sydney. The discipline of Rallysprinting is considered strategically important by the Rally Panel, as it is our number one gateway event for new competitors. The State championship is back. The panel has devoted much energy and resources into this area, and the 2015 championship is showing great signs. Bega has returned for 2015, as well as a new event in Glen Innes, which saw 51 entries on 28/3/15. The panel is aware of another landmark state championship event which will most likely return for 2016, and are very excited by that. We look forward to releasing the 2016 calendar later in the year. The DRS in 2015 has been split into 2, which allows for 4WD turbo cars. Whilst numbers in the DRS4 component are up, the participation in the 2WD sections is lower than last year at this stage. Number in Hyundai series are also down, but we are aware of at least 3 crews who are planning on contesting the later rounds. -

The Chesire Magazine Coolscupting in Anassa 04/03/2020

EARLY SPRING 2020 s ISSUE 073 Back In G A Family FreddieE Flintoff discussesR the new Top Gear series Football We trial Rio Ferdinand’s Football Escapes camp e ut & B a y Is the Ferrari Portofino more than A BEAST just a pretty face? Travel news WORDS:CRAIG HOUGH Hotel Du Cap-Eden-Roc Turns 150 Hidden away at the Southern-most tip of the Cap d’Antibes, the award-winning Hotel du Cap-Eden- Roc is considered one of the most beautiful properties in the world, and certainly the most glamourous place to stay on the French Riviera. Queen Victoria frst visited the French Riviera in 1882, drawn by warmer winters, and took with her a steady stream of English aristocrats, thereby sealing the Riviera’s reputation for years to come. As the iconic hotel celebrates its 150th year in 2020, it takes a look back at its origin as a writers’ retreat for the creatively spirited. Its location was always a place of great beauty and inspiration, which captured the attention of Auguste de Villemessant, the talented founder of Le Figaro, who realised its potential and built the elegant Villa Soleil in 1870 in the heart of what he deemed ‘paradise’. www.oetkercollection.com The Great Garden Escape This spring and summer, celebrate all things Somerset as ‘The Great Garden Escape to The Newt in Somerset’ returns with a host of new experiences and tours. Starting every weekend from 10 April – 27 September, a designated frst-class carriage will take guests from London Paddington to Castle Cary on a scenic journey deep into the West Country to discover the UK’s most exciting country estate and cultivated gardens. -

Broadcast Bulletin Issue Number

Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin Issue number 179 4 April 2011 1 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 179 4 April 2011 Contents Introduction 3 Standards cases In Breach Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (comments about Harvey Price) Channel 4, 7 December 2010, 22:00 5 [see page 37 for other finding on Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (mental health sketch and other issues)] Elite Days Elite TV (Channel 965), 30 November 2011, 12:00 to 13:15 Elite TV (Channel 965), 1 December 2010, 13:00 to 14:00 Elite TV 2 (Channel 914), 8 December 2010, 10.00 to 11:30 Elite Nights Elite TV (Channel 965), 30 November 2011, 22:30 to 23:35 Elite TV 2 (Channel 914), 6 December 2010, 21:00 to 21:25 Elite TV (Channel 965), 16 December 2010, 21:00 to 21:45 Elite TV (Channel 965), 22 December 2010, 00:50 to 01:20 Elite TV (Channel 965), 4 January 2011, 22:00 to 22:30 13 Page 3 Zing, 8 January 2011, 13:00 27 Deewar: Men of Power Star India Gold, 11 January 2011, 18:00 29 Bridezilla Wedding TV, 11 and 12 January 2011, 18:00 31 Resolved Dancing On Ice ITV1, 23 January 2011, 18:10 33 Not in Breach Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (mental health sketch and other issues) Channel 4, 30 November 2010 to 29 December 2010, 22:00 37 [see page 5 for other finding on Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (comments about Harvey Price)] Top Gear BBC2, 30 January 2011, 20:00 44 2 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 179 4 April 2011 Advertising Scheduling Cases In Breach Breach findings table Code on the Scheduling of Television Advertising compliance reports 47 Resolved Resolved findings table Code on the Scheduling of Television Advertising compliance reports 49 Fairness and Privacy cases Not Upheld Complaint by Mr Zac Goldsmith MP Channel 4 News, Channel 4, 15 and 16 July 2010 50 Other programmes not in breach 73 3 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 179 4 April 2011 Introduction The Broadcast Bulletin reports on the outcome of investigations into alleged breaches of those Ofcom codes and licence conditions with which broadcasters regulated by Ofcom are required to comply. -

Top Gear Top Gear

Top Gear Top Gear The Canon C300, Sony PMW-F55, Sony NEX-FS700 capable of speeds of up to 40mph, this was to and ARRI ALEXA have all complemented the kit lists be as tough on the camera mounts as it no doubt on recent shoots. As you can imagine, in remote was on Clarkson’s rear. The closing shot, in true destinations, it’s essential to have everything you need Top Gear style, was of the warning sticker on Robust, reliable at all times. A vital addition on all Top Gear kit lists is a the Gibbs machine: “Normal swimwear does not and easy to use, good selection of harnesses and clamps as often the adequately protect against forceful water entry only suitable place to shoot from is the roof of a car, into rectum or vagina” – perhaps little wonder the Sony F800 is or maybe a dolly track will need to be laid across rocks then that the GoPro mounted on the handlebars the perfect tool next to a scarily fast river. Whatever the conditions was last seen sinking slowly to the bottom of the for filming on and available space, the crew has to come up with a lake! anything from solution while not jeopardising life, limb or kit. As one In fact, water proved to be a regular challenge car boots and of the camera team says: “We’re all about trying to stay on Series 21, with the next stop on the tour a one step ahead of the game... it’s just that often we wet Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps in Belgium, roofs to onboard don’t know what that game is going to be!” where Clarkson would drive the McLaren P1. -

The Clarkson Controversy: the Impact of a Freewheeling Presenter on The

The Clarkson Controversy: the Impact of a Freewheeling Presenter on the BBC’s Impartiality, Accountability and Integrity BA Thesis English Language and Culture, Utrecht University International Anglophone Media Studies Laura Kaai 3617602 Simon Cook January 2013 7,771 Words 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Theoretical Framework 4 2.1 The BBC’s Values 4 2.1.2 Impartiality 5 2.1.3 Conflicts of Interest 5 2.1.4 Past Controversy: The Russell Brand Show and the Carol Thatcher Row 6 2.1.5 The Clarkson Controversy 7 2.2 Columns 10 2.3 Media Discourse Analysis 12 2.3.2 Agenda Setting, Decoding, Fairness and Fallacy 13 2.3.3 Bias and Defamation 14 2.3.4 Myth and Stereotype 14 2.3.5 Sensationalism 14 3. Methodology 15 3.1 Columns by Jeremy Clarkson 15 3.1.2 Procedure 16 3.2 Columns about Jeremy Clarkson 17 3.2.2 Procedure 19 4. Discussion 21 4.1 Columns by Jeremy Clarkson 21 4.2 Columns about Jeremy Clarkson 23 5. Conclusion 26 Works Cited 29 Appendices 35 3 1. Introduction “I’d have them all shot in front of their families” (“Jeremy Clarkson One”). This is part of the comment Jeremy Clarkson made on the 2011 public sector strikes in the UK, and the part that led to the BBC receiving 32,000 complaints. Clarkson said this during the 30 December 2011 live episode of The One Show, causing one of the biggest BBC controversies. The most widely watched factual TV programme in the world, with audiences in 212 territories worldwide, is BBC’s Top Gear (TopGear.com). -

Al Via La 25A Stagione Di Top Gear Con Matt Leblanc, Chris Harris, Rory

VENERDì 10 MAGGIO 2019 Da lunedì 13 maggio alle 21.30 su Spike (canale 49 del dtt), arriva in prima tv assoluta la 25a stagione di Top Gear, il più famoso CarShow della Tv. Al via la 25a stagione di Top Gear con Matt Leblanc, Chris Harris, Rory Reyd e The Stig Il mondo della auto, e tutto ciò che si muove a motore, raccontato con una buona dose di humor tipicamente british e una parte di sana irriverenza: Top Gear è uno dei programmi più longevi della televisione, Da lunedì 13 maggio a partire dalle 21.30 su una pietra miliare dell'intrattenimento automobilistico. Prodotto per SPIKE oltre 20 anni dalla BBC, ha raccolto enorme successo nelle televisioni di tutto il mondo. CRISTIAN PEDRAZZINI Ogni lunedì saranno trasmessi due nuovi episodi della serie che vede protagonisti Matt LeBlanc, celebre per la sua interpretazione di Joey Tribbiani nella popolare sitcom Friends della NBC, Chris Harris firma prestigiosa di molte riviste automobilistiche, e Rory Reid, presentatore televisivo specializzato in motori e tecnologia. I tre conduttori daranno [email protected] vita a sfide originali e entusiasmanti alle quali Top Gear ci ha abituato. SPETTACOLINEWS.IT Immancabile la presenza di The Stig che nel corso della stagione metterà alla frusta bolidi come la McLaren 720S, la Ferrari 812 Superfast, la Chevrolet Camaro e la Alpine A110. Nel primo episodio della serie LeBlanc, Harris e Reid andranno nello Utah, per celebrare il 116° anniversario del V8. Qui testeranno delle nuove macchine che montano questo tipo di motore: LeBlanc guiderà una Ford Shelby Mustang GT350R, Reid una Jaguar F-Type SVR e Harris la McLaren 570GT.