The Clarkson Controversy: the Impact of a Freewheeling Presenter on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

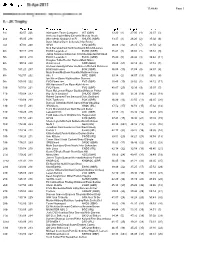

Relay Results

11:48:48 Page 1 1st 92:57 226 Interlopers Team Compass INT (GBR) 33:20 (1) 27:00 (4) 32:37 (3) Anthony Squire/Oleg Chepelin/Murray Strain 2nd 95:05 236 Who needs Graham? or R SHUOC (GBR) 33:37 (3) 26:26 (2) 35:02 (6) Dave Adams/Dave Schorah/John Rocke 3rd 97:03 240 SYO1 SYO (GBR) 36:28 (12) 28:37 (7) 31:58 (2) Nick Barrable/Neil Northrop/David Brickhill-Jones 4th 97:17 219 EUOC Legends 2 EUOC (GBR) 35:41 (7) 26:03 (1) 35:33 (9) Jamie Stevenson/Duncan Coombs/Alasdair Mcclead 5th 99:13 218 EUOC Legends 1 EUOC (GBR) 35:49 (8) 26:42 (3) 36:42 (11) Douglas Tullie/Hector Haines/Mark Nixon 6th 99:14 230 Robin Hood NOC (GBR) 39:48 (21) 28:14 (6) 31:12 (1) Andrew Llewellyn/Peter Hodkinson/Richard Robinson 7th 101:21 207 BOK Hurricanes BOK (GBR) 36:05 (10) 31:09 (8) 34:07 (4) Mark Bown/Matthew Franklin/Matthew Crane 8th 102:57 202 Aire 1 AIRE (GBR) 33:34 (2) 34:07 (13) 35:16 (8) Ian Nixon/Steve Watkins/Ben Stevens 9th 105:00 222 FVO Flyers too FVO (GBR) 38:46 (19) 28:02 (5) 38:12 (17) Will Hensman/Tom Ryan/Kyle Heron 10th 107:53 221 FVO Flyers FVO (GBR) 40:07 (25) 32:39 (9) 35:07 (7) Ross McLennan/Roger Goddard/Marcus Pinker 11th 110:04 237 Big city in England SHUOC (GBR) 36:03 (9) 35:39 (18) 38:22 (18) Robert Gardner/Tom Beasant/Chris Smithard 12th 110:09 208 BOK Typhoons BOK (GBR) 36:39 (13) 32:55 (11) 40:35 (20) Duncan Girtwistle/Keith Agmen/Huw Stradling 13th 110:17 201 3ROCkets 3ROC (IRL) 37:52 (17) 34:53 (15) 37:32 (14) Colm Moran/Andrew Quin/Gerard Butler 14th 110:29 245 Lakeland OC LOC (GBR) 34:18 (4) 33:42 (12) 42:29 (24) Todd Oates/Jack -

Pressreader Magazine Titles

PRESSREADER: UK MAGAZINE TITLES www.edinburgh.gov.uk/pressreader Computers & Technology Sport & Fitness Arts & Crafts Motoring Android Advisor 220 Triathlon Magazine Amateur Photographer Autocar 110% Gaming Athletics Weekly Cardmaking & Papercraft Auto Express 3D World Bike Cross Stitch Crazy Autosport Computer Active Bikes etc Cross Stitch Gold BBC Top Gear Magazine Computer Arts Bow International Cross Stitcher Car Computer Music Boxing News Digital Camera World Car Mechanics Computer Shopper Carve Digital SLR Photography Classic & Sports Car Custom PC Classic Dirt Bike Digital Photographer Classic Bike Edge Classic Trial Love Knitting for Baby Classic Car weekly iCreate Cycling Plus Love Patchwork & Quilting Classic Cars Imagine FX Cycling Weekly Mollie Makes Classic Ford iPad & Phone User Cyclist N-Photo Classics Monthly Linux Format Four Four Two Papercraft Inspirations Classic Trial Mac Format Golf Monthly Photo Plus Classic Motorcycle Mechanics Mac Life Golf World Practical Photography Classic Racer Macworld Health & Fitness Simply Crochet Evo Maximum PC Horse & Hound Simply Knitting F1 Racing Net Magazine Late Tackle Football Magazine Simply Sewing Fast Bikes PC Advisor Match of the Day The Knitter Fast Car PC Gamer Men’s Health The Simple Things Fast Ford PC Pro Motorcycle Sport & Leisure Today’s Quilter Japanese Performance PlayStation Official Magazine Motor Sport News Wallpaper Land Rover Monthly Retro Gamer Mountain Biking UK World of Cross Stitching MCN Stuff ProCycling Mini Magazine T3 Rugby World More Bikes Tech Advisor -

† the Funeral of the Late Kathleen Kadir Will Take Place This Friday at 10

Catholic Church MASS INTENTIONS Sat 22 Nov 6.00pm Luke Wall (Anniversary) 60 Highbury Park Sun 23 Nov 9.00am Bianca Mansi (Anniversary) London N5 2XH 11.00am Levi Cronin & Pat Whitbread (RIP) T 020 7226 0257 Mon 24 Nov 9.15am The Holy Souls E [email protected] Tues 25 Nov 9.15am Carmela & Emile Krawcuz (RIP) Wed 26 Nov 9.15am The Holy Souls www.stjoanofarcparish.co.uk Thu 27 Nov 9.15am Francis Trapani (RIP) Parish Blog Fri 28 Nov 8.00am Margaret Gallagher (Intentions) www.stjoanofarcparishuk.wordpre Sat 29 Nov 10.00am The Holy Souls ss.com/ 6.00pm Michael McManus (Anniversary) Rev Gerard G King Sun 30 Nov 9.00am For You The People 11.00am Mary Harrington (Anniversary) Parish Priest Sunday, 23 November, 2014 NEWSLETTER Our Lord Jesus Christ, King of the Universe First Communion Catechists’ Meeting this Monday Pope Having Showers Built in Vatican Introductionfor Rome's evening at 7.30pm in the presbytery. Today we celebrateHomeless Christ T ashe ourVatican king. has We announced will learn about that the the Holy values Father of love andhas compassion commissioned in God’s three kingdom showers and to behow built Jesus for judgesuse by histhe Calling all “Facebook” users! When visiting “Facebook”, homeless in the area under the colonnades of followers.St. Peter’s please add “My Hospital Prayer and Activities Book” as a Square. The showers will be installed in an existing lavatory “like”, to aid its publicity. This unique and original Catholic block used by tourists and pilgrims. An experience of the publication aims to help children pray if their patients are in Pope’s almoner, Archbishop Konrad Krajewski,Penitential led to Act the hospital. -

Who Wants to Be a Millionaire Host on 'Worst Year'

7 Ts&Cs apply Iceland give huge discount Claire King health: Craig Revel Horwood Kate Middleton pregnant Jenny Ryan: ‘The cat is out to emergency service Emmerdale star's health: ‘It was getting with twins on royal tour in the bag’ The Chase quizzer workers - find… diagnosis ‘I was worse’ Strictly… Pakistan?… announces… Jeremy Clarkson: ‘Wanted to top myself’ Who Wants To Be A Millionaire host on 'worst year' JEREMY CLARKSON - who fronts ITV show Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? - shared his thoughts on a recent study which claimed 1978 was the “worst year” in British history. Who Wants to Be a Millionaire: Jeremy criticises the contestant Earlier this week, researchers from Warwick University claimed people of Britain were at their most unhappy in 1978. The latter year and the first two months of 1979 are best remembered for the Winter of Discontent, where strikes took place and caused various disruptions. ADVERTISING 1/6 Jeremy Clarkson (/search?s=jeremy+clarkson) shared his thoughts on the study as he recalled his first year of working during the strikes. PROMOTED STORY 4x4 Magazine: the SsangYong Musso is a quantum leap forward (SsangYong UK)(https://www.ssangyonggb.co.uk/press/first-drive-ssangyong-musso/56483&utm-source=outbrain&utm- medium=musso&utm-campaign=native&utm-content=4x4-magazine?obOrigUrl=true) In his column with The Sun newspaper, he wrote: “It’s been claimed that 1978 was the worst year in British history. RELATED ARTICLES Jeremy Clarkson sports slimmer waistline with girlfriend Lisa Jeremy Clarkson: Who Wants To Be A Millionaire host on his Hogan weight loss (/celebrity-news/1191860/Jeremy-Clarkson-weight-loss-girlfriend- (/celebrity-news/1192773/Jeremy-Clarkson-weight-loss-health- Lisa-Hogan-pictures-The-Grand-Tour-latest-news) Who-Wants-To-Be-A-Millionaire-age-ITV-Twitter-news) “I was going to argue with this. -

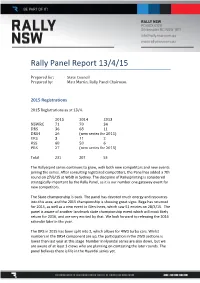

Rally Panel Report 13/4/15

Rally Panel Report 13/4/15 Prepared for: State Council Prepared by: Matt Martin, Rally Panel Chairman. 2015 Registrations 2015 Registrations as at 13/4. 2015 2014 2013 NSWRC 71 70 34 DRS 36 68 11 DRS4 26 (new series for 2015) ERS 3 11 2 RSS 68 58 6 PRS 27 (new series for 2015) Total 231 207 53 The Rallysrpint series continues to grow, with both new competitors and new events joining the series. After consulting registered competitors, the Panel has added a 7th round on 27/6/15 at WSID in Sydney. The discipline of Rallysprinting is considered strategically important by the Rally Panel, as it is our number one gateway event for new competitors. The State championship is back. The panel has devoted much energy and resources into this area, and the 2015 championship is showing great signs. Bega has returned for 2015, as well as a new event in Glen Innes, which saw 51 entries on 28/3/15. The panel is aware of another landmark state championship event which will most likely return for 2016, and are very excited by that. We look forward to releasing the 2016 calendar later in the year. The DRS in 2015 has been split into 2, which allows for 4WD turbo cars. Whilst numbers in the DRS4 component are up, the participation in the 2WD sections is lower than last year at this stage. Number in Hyundai series are also down, but we are aware of at least 3 crews who are planning on contesting the later rounds. -

Highlight Der Woche: Top Gear Eps. 1

DMAX Programm Programmwoche 36, 01.09. bis 07.09.2012 Highlight der Woche: Top Gear Eps. 1 (16) Am Montag, 10.09.2012 um 20:15 Uhr Wehe wenn sie losgelassen: In der neuen Staffel testen die Jungs von "Top Gear" die tollsten Luxuskarossen - manchmal geht´s jedoch auch mit dem Mähdrescher in den Schnee oder dem Hubschrauber aufs Autodach… Die spektakulärsten Autos der Welt, Testfahrten auf dem Vulkan und jede Menge coole Sprüche: DMAX holt "Top Gear" - die Mutter aller Auto-Shows - nach Hause. Das weltweit erfolgreichste TV-Format rund ums Thema „fahrbarer Untersatz“ begeistert seine Zuschauer seit Jahren mit sensationellen Stunts, präzise recherchierten Beiträgen und gefürchteten Kfz-Kritiken. Mehr Leidenschaft fürs Auto geht nicht! Darin ist sich die riesige Fan-Gemeinde des Kult-Formats rund um den Globus einig. Ganz zu schweigen vom bissigen britischen Humor der Moderatoren Jeremy Clarkson, Richard Hammond und James May. Die ironischen Kommentare der Auto-Experten sind eben nicht zu toppen. Kurzum: Top Gear ist Kult! Know-how, Enthusiasmus und Faszination - die preisgekrönte BBC-Produktion hat mit DMAX in Deutschland die perfekte Heimat gefunden. "Als würde die Queen einen Tanga unterm Rock tragen!" - die Vergleiche, die Jeremy Clarkson in dieser Episode zieht, grenzen an Majestätsbeleidung. Doch der Top Gear-Experte ist vom schicken Interieur des Jaguar XJ so begeistert, dass er etwas über die Stränge schlägt. Da die luxuriöse V8- Raubkatze außerdem mächtig Dampf unterm Kessel hat, macht es Jeremy einen Riesenspaß auf der britischen Insel von Küste zu Küste zu brettern. Weitere Highlights dieser Episode: Porsche 959 und Ferrari F40 im Vergleich, sowie ein 3,5 Millionen Euro teuer NASA-Mondbuggy. -

The Chesire Magazine Coolscupting in Anassa 04/03/2020

EARLY SPRING 2020 s ISSUE 073 Back In G A Family FreddieE Flintoff discussesR the new Top Gear series Football We trial Rio Ferdinand’s Football Escapes camp e ut & B a y Is the Ferrari Portofino more than A BEAST just a pretty face? Travel news WORDS:CRAIG HOUGH Hotel Du Cap-Eden-Roc Turns 150 Hidden away at the Southern-most tip of the Cap d’Antibes, the award-winning Hotel du Cap-Eden- Roc is considered one of the most beautiful properties in the world, and certainly the most glamourous place to stay on the French Riviera. Queen Victoria frst visited the French Riviera in 1882, drawn by warmer winters, and took with her a steady stream of English aristocrats, thereby sealing the Riviera’s reputation for years to come. As the iconic hotel celebrates its 150th year in 2020, it takes a look back at its origin as a writers’ retreat for the creatively spirited. Its location was always a place of great beauty and inspiration, which captured the attention of Auguste de Villemessant, the talented founder of Le Figaro, who realised its potential and built the elegant Villa Soleil in 1870 in the heart of what he deemed ‘paradise’. www.oetkercollection.com The Great Garden Escape This spring and summer, celebrate all things Somerset as ‘The Great Garden Escape to The Newt in Somerset’ returns with a host of new experiences and tours. Starting every weekend from 10 April – 27 September, a designated frst-class carriage will take guests from London Paddington to Castle Cary on a scenic journey deep into the West Country to discover the UK’s most exciting country estate and cultivated gardens. -

Broadcast Bulletin Issue Number

Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin Issue number 179 4 April 2011 1 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 179 4 April 2011 Contents Introduction 3 Standards cases In Breach Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (comments about Harvey Price) Channel 4, 7 December 2010, 22:00 5 [see page 37 for other finding on Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (mental health sketch and other issues)] Elite Days Elite TV (Channel 965), 30 November 2011, 12:00 to 13:15 Elite TV (Channel 965), 1 December 2010, 13:00 to 14:00 Elite TV 2 (Channel 914), 8 December 2010, 10.00 to 11:30 Elite Nights Elite TV (Channel 965), 30 November 2011, 22:30 to 23:35 Elite TV 2 (Channel 914), 6 December 2010, 21:00 to 21:25 Elite TV (Channel 965), 16 December 2010, 21:00 to 21:45 Elite TV (Channel 965), 22 December 2010, 00:50 to 01:20 Elite TV (Channel 965), 4 January 2011, 22:00 to 22:30 13 Page 3 Zing, 8 January 2011, 13:00 27 Deewar: Men of Power Star India Gold, 11 January 2011, 18:00 29 Bridezilla Wedding TV, 11 and 12 January 2011, 18:00 31 Resolved Dancing On Ice ITV1, 23 January 2011, 18:10 33 Not in Breach Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (mental health sketch and other issues) Channel 4, 30 November 2010 to 29 December 2010, 22:00 37 [see page 5 for other finding on Frankie Boyle’s Tramadol Nights (comments about Harvey Price)] Top Gear BBC2, 30 January 2011, 20:00 44 2 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 179 4 April 2011 Advertising Scheduling Cases In Breach Breach findings table Code on the Scheduling of Television Advertising compliance reports 47 Resolved Resolved findings table Code on the Scheduling of Television Advertising compliance reports 49 Fairness and Privacy cases Not Upheld Complaint by Mr Zac Goldsmith MP Channel 4 News, Channel 4, 15 and 16 July 2010 50 Other programmes not in breach 73 3 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 179 4 April 2011 Introduction The Broadcast Bulletin reports on the outcome of investigations into alleged breaches of those Ofcom codes and licence conditions with which broadcasters regulated by Ofcom are required to comply. -

Top Gear Top Gear

Top Gear Top Gear The Canon C300, Sony PMW-F55, Sony NEX-FS700 capable of speeds of up to 40mph, this was to and ARRI ALEXA have all complemented the kit lists be as tough on the camera mounts as it no doubt on recent shoots. As you can imagine, in remote was on Clarkson’s rear. The closing shot, in true destinations, it’s essential to have everything you need Top Gear style, was of the warning sticker on Robust, reliable at all times. A vital addition on all Top Gear kit lists is a the Gibbs machine: “Normal swimwear does not and easy to use, good selection of harnesses and clamps as often the adequately protect against forceful water entry only suitable place to shoot from is the roof of a car, into rectum or vagina” – perhaps little wonder the Sony F800 is or maybe a dolly track will need to be laid across rocks then that the GoPro mounted on the handlebars the perfect tool next to a scarily fast river. Whatever the conditions was last seen sinking slowly to the bottom of the for filming on and available space, the crew has to come up with a lake! anything from solution while not jeopardising life, limb or kit. As one In fact, water proved to be a regular challenge car boots and of the camera team says: “We’re all about trying to stay on Series 21, with the next stop on the tour a one step ahead of the game... it’s just that often we wet Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps in Belgium, roofs to onboard don’t know what that game is going to be!” where Clarkson would drive the McLaren P1. -

Annual Report on the BBC 2019/20

Ofcom’s Annual Report on the BBC 2019/20 Published 25 November 2020 Raising awarenessWelsh translation available: Adroddiad Blynyddol Ofcom ar y BBC of online harms Contents Overview .................................................................................................................................... 2 The ongoing impact of Covid-19 ............................................................................................... 6 Looking ahead .......................................................................................................................... 11 Performance assessment ......................................................................................................... 16 Public Purpose 1: News and current affairs ........................................................................ 24 Public Purpose 2: Supporting learning for people of all ages ............................................ 37 Public Purpose 3: Creative, high quality and distinctive output and services .................... 47 Public Purpose 4: Reflecting, representing and serving the UK’s diverse communities .... 60 The BBC’s impact on competition ............................................................................................ 83 The BBC’s content standards ................................................................................................... 89 Overview of our duties ............................................................................................................ 96 1 Overview This is our third -

INTRODUCING the TOP GEAR LIMITED EDITION BUGG BBQ from BEEFEATER Searing Performance for the Meat Obsessed Motorist

PRESS RELEASE INTRODUCING THE TOP GEAR LIMITED EDITION BUGG BBQ FROM BEEFEATER Searing Performance for the Meat Obsessed Motorist “It’s Flipping Brilliant” Sydney, Australia, 19 November 2012 BeefEater, the Australian leaders in barbecue technology, has partnered with BBC Worldwide Australasia to create an innovative and compact Top Gear Limited Edition BUGG® (BeefEater Universal Gas Grill) BBQ, that will make you the envy of your mates. The Limited Edition BBQ from BeefEater comes with an exclusive Top Gear accessory bundle which includes a Stig oven mitt and apron to help you look the part while cooking. It also features a bespoke Top Gear gauge and tyre‐track temperature control knob to keep you on track whilst perfecting your meat. ‘Top Gear’s Guide on How Not to BBQ’ is also included, with helpful tips such as ‘do not attempt to modify your barbecue by fitting an aftermarket exhaust’ and ‘this barbecue is not suitable for children, or adults who behave like children’ guiding users through those trickier BBQ moments. The BBQ launches in Australia just in time for Christmas at Harvey Norman and other leading independent retailers, and will be available in the UK and Europe when the weather’s a little better. “A cool white hood, precision controls, bespoke gauges and a high performance ignition – what a way to convince the meat obsessed motorist to get out of the garage and cook dinner! This new Top Gear Limited Edition BUGG BBQ from BeefEater is a high performance vehicle, making cooking ability an optional extra,” says Elie Mansour, BBC Worldwide Australasia’s Manager Licensed Consumer Products. -

All New Top Gear! Coming to BBC Knowledge This February, First on Foxtel

Thursday January 23, 2014 All New Top Gear! Coming to BBC Knowledge this February, first on Foxtel The boys are back with an all new season of Top Gear, jam-packed with all of the thrills and spills we have come to expect from the world’s favourite car show. Top Gear Series 21 will premiere Sunday February 9 at 8.30pm on BBC Knowledge. In this new series, Jeremy Clarkson, Richard Hammond and James May embark on a huge road trip across Ukraine in three small cars with even smaller engines. They re-live the glory days of the 1980s in three ‘classic’ hot hatchbacks, and have a ham-fisted crack at making a public safety film for the government. There’s also the new Alfa 4C sports car racing a very unusual quad bike, the sensational McLaren P1 tearing a strip off Belgium, an insane six-wheeled Mercedes in the desert, and the unusual sight of James May in a Caterham. And as if that wasn’t enough, the series includes a mad-capped two-part adventure across the wilds of Burma as the presenters take three lorries on what could be Top Gear’s toughest challenge to date. Fan favourite, ‘Star in a Reasonably Priced Car’ will return to our screens once again, with Downton Abbey’s Hugh Bonneville taking to the track in the first episode of the new series. Top Gear fans can experience their favourite car show in the flesh this March when Jeremy Clarkson, James May and The Stig travel to Australia for Top Gear Festival Sydney, held at Sydney Motorsport Park on March 8-9.