The October 1P, 107, Pow Pemonstration at the *Faculty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

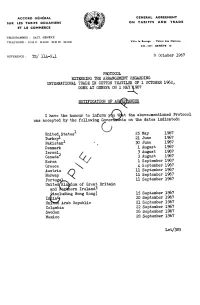

9 October 1967 PROTOCOL EXTENDING the ARRANGEMENT

ACCORD GÉNÉRAL GENERAL AGREEMENT SUR LES TARIFS DOUANIERS ON TARIFFS AND TRADE ET LE COMMERCE m TELEGRAMMES : GATT, GENÈVE TELEPHONE: 34 60 11 33 40 00 33 20 00 3310 00 Villa le Bocage - Palais des Nations CH-1211 GENÈVE tO REFERENCE : TS/ 114--5*! 9 October 1967 PROTOCOL EXTENDING THE ARRANGEMENT REGARDING INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN COTTON TEXTILES OF 1 OCTOBER 1962, DONE AT GENEVA ON 1 MAY U967 NOTIFICATION OF ACCEPTANCES I have the honour to inform yew. tHat the above-mentioned Protocol was accepted by the following Governments on the dates indicated: United States G 25 May 1967 Turkeys- 21 June 1967 Pakistan 30 June 1967 Denmark 1 August 1967 Israel, 3 August 1967 Canada* 3 August 1967 Korea 1 September 1967 Greece U September 1967 Austria 11 September 1967 Norway 11 September 1967 Portuga 11 Septembei• 1967 United/kinkdom of Great Britain and ItacAnern Ireland^ ^including Hong Kong) 15 September 1967 Irttia^ 20 September 1967 Unrtrea Arab Republic 21 September 1967 Colombia 22 September 1967 Sweden 26 September 1967 Mexico 28 September 1967 Let/385 - 2 - Republic of China 28 September 1967 Finland 29 September 1967 Belgium 29 September 1967 France 29 September 1967 Germany, Federal Republic 29 September 1967 Italy 29 September 1967 Luxemburg 29 September 1967 Netherlands, Kingdom of the (for its European territory only) 29 September 1967 Japan ,. 30 September 1967 Australia 30 September 1967 Jamaica 2 October 1967 Spain 3 October 1967 Acceptance by the Governments of Italy and of the Federal Republic of Germany was made subject to ratification. The Protocol entered into force on 1 October 1967, pursuant to its paragraph 5. -

OCTOBER, 1967 Copied from an Original at the History Center

Copied from an original at The History Center. www.TheHistoryCenterOnline.com 2013:023 OCTOBER, 1967 Copied from an original at The History Center. www.TheHistoryCenterOnline.com 2013:023 rom the PRESIDENT'S DESK ... Fellow Employees: There is a certain quality in some people which makes them a good team member whether it be at play or in th e workshop. This quality is usually inherent in a Winner. In a football game, th e coach would call it " team spirit." On the school campus, th e student or professor refers to it as "school pride." Jn th e armed services, the soldier or sailor expresses it as a phrase called "esprit de Corps." But in this work-a-day world, it is merely called " loyalty." On the wall in Mutt Barr's office is a plaque containing these famous words by Elbert Hubbard: "If you work for a man, in heaven's name work for him; Speak well of him and stand by the institution he represents. Remember, an ounce of loyalty is worth a pound of clever- ness. If you must growl, condemn and enternally find fault, why re ign your position. And when you are outside, damn to your heart's content But as long as you are part of the institution do not con demn it. If you do, the first high wind that comes along will blow you away and probably yo u will never know why." I don't believe there is another quality more important to the success of an organization than the loyalty of its employees. -

City Employment in 1967

GOVERNMENT EMPLOYMENT / GE67 No.2 CITY EMPLOYMENT IN 1967 Municipal governments in the United States During the 5 years from 1962 to 1967, city made salary and wage payments for October 1967 employment (on a full-time equivalent basis) amounting to $987 million. This sum represented rose approximately 19 percent and municipal payrolls for 2,060,000 employees--1,70lJ,000 of payrolls increased 46 percent. Average monthly them engaged on a full-time basis and the other earnings of fUll-time city employees concerned 351,000 paid only for part-time services. The with education rose 15 percent in this 5-year part-time component is accounted for mainly by period. The average for other full- time munic small municipalities, and includes numerous ipal employees went up 27 percent. elected officials and paid volunteer firemen- groups that ordinarily receive only nominal The full- time equivalent number of munici pal employees in October 1967, other than for compensation for their services. education amounted to 1,444,000 persons. This When part-time city employees are counted was equal to an average of 123 employees for each in terms of average pay rates for fUll-time work 10,000 municipal inhabitants, as reported in in corresponding functions, they are found to be table 2. equivalent to only 57,000 full-time employees. Accordingly, the total of municipal employment FUNCTIONS OF CITY GOVERNMENTS in October 1967, on a full-time equivalent basis, ) is calculated at 1,766,000 persons. Individual cities differ Widely in the range of their responsibilities. Certain important These figures indicate increases from services needed in urban areal:i mayor may not October 1966 as follows: Number of employees be provided by the municipal government, depend (full-time equivalent), up some 65 thousand. -

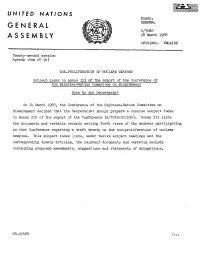

General Assembly

UNITED NATIONS Distr. GENERAL GENERAL A/7080 ASSEMBLY 28 March 1968 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH Twenty-second session Agenda item 28 (a) NON-PROLIFERATION OF NUCLEAR WEAPONS Subject index to annex HI of the report of the Conference of the Eighteen-Nation Committee on Disarmament Note by the Secretariat On l4 March 1968, the Conference of the Eighteen-Nation Committee on Disarmament decided that the Secretariat should prepare a concise subject index to annex III of the report of the Conference (A/7072-DC/230). Annex III lists the documents and verbatim records setting forth views of the members participating in that Conference regarding a draft treaty on the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons. This subject index lists, under twelve subject headings and the corresponding treaty articles, the relevant documents and verbatim records containing proposed amendments, suggestions and statements of delegations. 68-07488 I ... A/7080 English Page 2 CONTENTSY Page 1. General (preamble) •••••••••• • 3 Basic obligations (articles I and 11) • 6 3. Safeguards (article Ill) ••••••• • • 8 4. Peaceful uses of nuclear energy (article IV) • •• 11 5. Peaceful nuclear explosions (article V) • 14 6. Other measures of disarmament (article VI) • • •• • 17 7. Treaties for nuclear-free zones (article VII) 20 8. Amendments; review (article VIII) ••. 22 9. Signature; ratification; depository Governments; entry into force; 24 definition of nuclear-weapon State (article IX) • 10. Withdrawal; duration (article X) •••••••• • 26 11. Acceptable balance of mutual responsibilities and obligations )f the nuclear and non-nuclear Powers • 28 12. Security; security assurances .. • 30 Y The draft treaty articles referred to are those of the 1968 drafts of a treaty on the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons (draft of 11 March 1968, A/7072-DC/230, annex I; drafts of 18 January 1968: ibid, annex IV, documents ENDC/192/Rev.l and 193/Rev.l). -

National Gallery of Art Calendar of Events

NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART Sixth St. and Constitution Ave. Washington, D. C. 20565 CALENDAR OF EVENTS OCTOBER 1967 OCTOBER 1967 NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART NEW EXHIBITION Swiss Drawings: Masterpieces of Five Cen turies. Central Gallery. October 8 through October 29. NEW PUBLICATION Catalogue. Swiss Drawings: Masterpieces of Five Centuries. 175 pages, 10" x 7^", with introduction and catalogue notes by Walter Hugelshofer, 127 illustrations. $3.00 postpaid. CONTINUING Ginevra de'Benci by Leonardo da Vinci. EXHIBITION New acquisition. Lobby B. 22" x 28" Color Reproductions: Cezanne, NEW Still Life; Constable, Wivenhoe Park, Essex; REPRODUCTIONS Corot, Ville d'Avray; Dali, The Sacrament of the Last Stopper; Fragonard, A Young Reading; Goya, Senora Sabasa Garcia; nett, My Gems; Homer, Breezing Up; Monet, Banks of the Seine, Vetheuil; Picasso, Le Gourmet; Rembrandt, A Girl with a Broom; Renoir, A Girl with a Watering Can. $3.00 each postpaid. Reproductions of bronze heads of Deputies by Honore Daumier: Comte de Monidosier (The Cheat and Shrewd). $18.50; Jean Charles Persil (The Scrupulous). $18.50; Jacques Lefebvre (The Sharp and Cunning Wit). $18.50; Comte de Lameth (The Irresolute). $15.00. 1967 Christmas Card Available upon request, free of charge, with Catalogue black-and-white illustrations and descrip tions of 48 Christmas cards and notefolders reproduced from paintings, sculptures, and prints in the Gallery Collection. ACOUSTIGUIDE A new recorded 45-minute tour of the Is? tional Gallery with the Director. A sm all portable unit may be rented for 25$ for one, 35$ for two persons. LecTour A radio lecture device is installed in 28 ex hibition galleries. -

New York, 31 January 1967 ENTRY INTO FORCE 4 October 1967, In

5. PROTOCOL RELATING TO THE STATUS OF REFUGEES New York, 31 January 1967 . ENTRY INTO FORCE 4 October 1967, in accordance with article VIII. REGISTRATION: 4 October 1967, No. 8791. STATUS: Parties: 146. TEXT: United Nations, Treaty Series , vol. 606, p. 267. Note: On the recommendation of the Executive Committee of the Programme of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the High Commissioner submitted the draft of the above-mentioned Protocol to the General Assembly of the United Nations, through the Economic and Social Council, in the addendum to his report concerning measures to extend the personal scope of the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees. The Economic and Social Council, in resolution 1186 (XLI)1 of 18 November 1966, took note with approval of the draft Protocol and transmitted the said addendum to the General Assembly. The General Assembly, in resolution 2198 (XXI)2 of 16 December 1966, took note of the Protocol and requested the Secretary-General "to transmit the text of the Protocol to the States mentioned in article V thereof, with a view to enabling them to accede to the Protocol." . Accession(a), Accession(a), Participant Succession(d) Participant Succession(d) Afghanistan .............................................30 Aug 2005 a Colombia ................................................ 4 Mar 1980 a Albania....................................................18 Aug 1992 a Congo .....................................................10 Jul 1970 a Algeria ................................................... -

50 of 24 October 1967 Concerning

DEFRENNE v SABENA OPINION OF MR ADVOCATE-GENERAL TRABUCCHI DELIVERED ON 10 MARCH 1976 1 Mr President, completion of 40 years of age. This Members of the Court, clause was applied to Miss Defrenne on 15 February 1968. 1. After the solemn declarations made by the Heads of State and of Government Under the terms of her contract, she in Paris in 1972 on the importance received a grant equivalent to one year's of the social aspects of European salary. Miss Defrenne then took two integration, here we have a private actions: individual, a female worker, who succeeds in obtaining from her national On 9 February 1970 she applied to the court a reference for a preliminary ruling Belgian Conseil d'Etat for annulment of on the interpretation of the provision in the Royal Decree of 3 November which, the EEC Treaty which establishes the for civil aviation crew, laid down special principle of equal treatment for men and rules governing the acquisition of the women in the field of employment. A right to a pension and special procedures reference which in itself is of very for implementation of Royal Decree No modest financial importance provides an 50 of 24 October 1967 concerning opportunity for this Court to clarify retirement pensions and survivors certain aspects of the protection which pensions for employed persons, on the fundamental rights are entitled to receive basis of which her pension had been calculated. within the framework of the Community structure. Giving a preliminary ruling on a This is the second reference for a reference made to it by the Belgian court' preliminary ruling which bears the name (in Case 80/70), this Court, in its of Miss G. -

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

RESTRICTED • GENERAL AGREEMENT ON COT/77/Add.l 14 November 1967 TARIFFS AND TRADE Special Distribution COTTON TEXTILES COMMITTEE Protocol Extending the Arrangement Regarding International Trade in Cotton Textiles of 1 October 1962 Acceptances by Participating Countries Note by the Chairman Addendum * The Protocol Extending the Arrangement Regarding International Trade in Cotton Textiles for a period of three years, beginning on 1 October 1967, was accepted by all the governments party to this Arrangement on the dates indicated: United States 25 May 1967 Turkey 21 June 1967 Pakistan 30 June 1967 Denmark 1 August 1967 Israel 3 August 1967 Canada 3 August 1967 Korea 1 September 1967 Greece A September 1967 Austria 11 September 1967 Norway 11 September 1967 Portugal 11 September 1967 United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ir 3land (including Hong Kong) 15 September 1967 India-5 20 September 1967 United Arab Republic 21 September 1967 Colombia 22 September 1967 Sweden 26 September 1967 Mexico 2S September 1967 Subject to the maintenance of the Protocol relating to the reservation attached by the Government of Canada to its acceptance of the original Arrangement of 1 October 1962. o Subject to the maintenance of the Protocol relating to the United Kingdom reservation attached to the original Arrangement of 1 October 1962. 3 In accepting the Protocol, India addressed a communication to the Director-General relating to its acceptance, a copy of which is attached to this notification. COT/77/Md.l Page 2 Republic of China 28 September 1967 Finland 29 September 1967 Belgium 29 September 1967 France 29 September 1967 Germany, Federal Republic of 29 September 1967 Italy 29 September 1967 Luxemburg 29 September 1967 Netherlands, Kingdom of the (for its European territory and Surinam) 29 September 1967 Japan , 30 September 1967 Australia 30 September 1967 Jamaica 2 October 1967 Spain 3 October 1967 w Acceptance by the Governments of Italy and of the Federal Republic of Germany was made subject to ratification. -

Download (Pdf)

FEDERAL RESERVE statistical For immediate release ///<->• January 18, 1968 AtnOM)B MCE COMPANIES THE; PROPORTION OF USED CAR CONTRACTS LONGER THAN 30JONTHS HAS RISEN IN NOVEMBER TO A 3 YEAR PEAK. : -j 40 135 1965 1966 1967 MATURITY DISTRIBUTION - NEW CAR CONTRACTS 24 months 25-30 31-36 Over 36 Balloon No. of contracts or less months months months paper Total reported (000) 7o % % 7, % Seasonally adjusted "\ November 1967 15.2 2.8 . 80.9 , 0.4 0.7 100.0 104 October 1967 16.6 3.0 79.2 0.5 0.7 100.0 108 September 1967 14.3 2.6 81.8 . 0.6 0.7 100.0 104 August 1967 13.8 2.7 82.2 0.7 0.6 100.0 105 'Unadjusted November 1967 17.3 2.9 78.6 0.4 0.8 100.0 100 October 1967 16.7 3.0 79.2 0.4 0.7 ' 100.0 112 November 1966 17.0 3.3 78.7 0.5 0.5 100.0 117 MATURITY DISTRIBUTION - USED CAR CONTRACTS 18 months 19-24 25-30 Over 30 Balloon No. of contracts months months months paper . Total reported (000) °L 7o % 7. 7, Seasonally adjusted November 1967 j 6 .6 19.4 32.5 41.2 0.3 100.0 41 October 1967 i 7.1 19.4 37.0 36.1 0.4 100.0 51 September 1967 7.2 19.7 35.1 37.6 0.4 100.0 39 August 1967 7.9 19.0 35.1 37.6 0.4 100.0 45 Unadjusted November 1967 7.3 17.9 30.0 44.4 0.4 100.0 39 October 1967 7.5 20.1 32.4 39.5 0.5 100.0 43 38 November 1966 7.9 17.5 30.0 44.3 0.3 100.0 Note: Monthly data available on request for years 1960-66. -

World Health Organization Шшш Organisation Mondiale

*ND£x e d~ A23/AFL/1 WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION 20 March 1970 шШш ORGANISATION MONDIALE DE LA SANTÉ TWENTY-THIRD WORLD HEALTH ASSEMBLY Provisional agenda item 3.4 SITUATION REGARDING THE POSSIBILITIES FOR THE ACCEPTANCE OF AMENDMENTS TO THE CONSTITUTION OF WHO Pursuant to operative paragraph 2 of resolution WHA22.26, the Director-General has the honour to report to the Twenty-third World Health Assembly on the situation regarding the acceptance of the amendments to Articles 7, 2 and 24 and 25°q of the WHO Constitution. Thirty-nine Member States have now accepted the amendment to Article 7 and 40 the amendments to Articles 24 and 25 of the Constitution, The acceptances are listed respectively in Annexes A and В to this document. On the basis of the present membership of WHO, namely 128 Members, the two-thirds required for the entry-into-force of these amendments would be obtained when 86 acceptances had been received. 1 Off. Rec. Wld Hlth Org., 176, 11. 2 Handbook of Resolutions and Decisions, 10th ed., p. 299. 3 Handbook of Resolutions and Decisions, 10th ed., p. 300. A23/AFL/1 page 2 ANNEX A LIST OF COUNTRIES HAVING DEPOSITED A FORMAL INSTRUMENT OF ACCEPTANCE OF THE AMENDMENT TO ARTICLE 7 OF THE CONSTITUTION WITH THE SECRETARY-GENERAL OF THE UNITED NATIONS Name of country Date of deposit of formal instrument of acceptance 1. MAURITANIA 26 October 1965 2. ZAMBIA 22 November 1965 3. MADAGASCAR 26 November 1965 4. TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO 2 December 1965 5. IVORY COAST 6 December 1965 6. -

IRO Correspondence, October 1967

7/2/5 International Relations Office New Office (1956- ) Correspondence, 1967-72 Box 1: IRO Correspondence, October 1967 - June 1970 October, 1967 November, 1967 December, 1967 January, 1968 February, 1968 March, 1968 April, 1968 Includes Government Advisory Committee Meeting notes, May 1, 1968 May, 1968 June, 1968 Includes a list of delegates approved for IFLA meeting attendance, June 17, 1968 July, 1968 August, 1968 September, 1968 October, 1968 Includes International Relations Committee Agenda, October 30-31, 1968 November, 1968 December, 1968 January, 1969 Includes President’s Advisory Committee on Foreign Assistance summary, 1969 February, 1969 March, 1969 April, 1969 May, 1969 June, 1969 July, 1969 Includes Selected Aids for the Purchase of U.S. Publications and Briefing of Library Services Division, Office of Education, International Programs of A.L.A. August, 1969 September, 1969 October, 1969 November, 1969 December, 1969 Includes a summary of Jack Dalton’s Library Education and Research in Librarianship speech at the IFLA meetings in 1969 January, 1970 February, 1970 March, 1970 April, 1970 2 May, 1970 June, 1970 Includes 1969 Basis for National Planning of Library and Documentation Services in Colombia, Organization of American States Memorandum and A.L.A. and U.S.A.I.D. Basic Agreement No. AID/csd-1538 Task Order No. 1 Box 2: IRO Correspondence, July 1970 - October 1970 July, 1970 August, 1970 September, 1970 Includes an audit of Contract no. AID/csd-1538 Columbian and Tunisian Telegrams, May and November 1969 Letters to Individuals, 1969-72, plus scattered letters in alphabetical listings. A, 1970-72 Alonso Altamirano, 1969-71 Stanley Applegate, 1969-72 Lester Asheim, 1969-72 B, 1969-72 Includes an itinerary for Miss Mercedes Aleman Peter L. -

The Caveat, October 1967

Golden Gate University School of Law GGU Law Digital Commons Caveat Other Law School Publications 10-1967 The aC veat, October 1967 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/caveat Part of the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation "The aC veat, October 1967" (1967). Caveat. Paper 11. http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/caveat/11 This Newsletter or Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Other Law School Publications at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Caveat by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME III NO.2 GOLDEN GATE COLLEGE SCHOOL OF LAW OCTOBER 1967 A Student Chapter - National Lawyers Guild A VIEW ANOTHER VIEW The formation of a student chap Although some interpretations Golden Gate College School of ter of the National Lawyers Guild of academic freedom find such cred. Law will never be the same with the marks a distinct change in faculty its amusing or even endearing, from inception of a student chapter of the policy which formerly did not encour 1944 to 1956 (both before and after National Lawyers Guild. For with age the formation of student organ the "McCarthy era") the National the advent of the Guild will come a izations. The hospitable receipt of Lawyers Guild was frequently cited new activist spirit to the staid halls this organization with faculty part by committees in both houses of Con of Golden Gate. The organizers of icipation and announcements made in gress as a subversive organization, the Guild here at Golden Gate pro the law school office has apparently that is, a communist front.