War Memorials As Propaganda Art and the Development of a Nation's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Textile Accounts of Conflicts Linen Hall Library, Belfast January - March 2015 #Accountsni TEXTILE ACCOUNTS

Dia de Visita / Day of Visit Victoria Diaz Caro, 1988 Photo Martin Melaugh Oshima Hakko Museum collection, Japan Textile Accounts of Conflicts Linen Hall Library, Belfast January - March 2015 #accountsNI TEXTILE ACCOUNTS An exhibition of textiles OF CONFLICTS and associated memorabilia commissioned by the International Conflict Research Institute (INCORE), Ulster University, for the International Conference Accounts of the Conflict which took place in Belfast 17 & 18 November 2014. Bringing it now to the Linen Hall Library will allow exposure to an ample number of people and voice publically what the makers and sewers have endured and shared. In this exhibition, the first hand quilts, wall hangings, testimony of the destructive and memory cloths and multi-layered impact of conflict story cloths is drawn and human rights abuse, is narrated from Northern Ireland, in textile form and is accompanied England, Spain, Chile, Peru, by associated memorabilia. “War Argentina, Afghanistan, textiles are born from this urge to Palestine, Zimbabwe, South find a new language with which to Africa, Germany, Brazil, Canada tell a story”1. and Colombia. Using mostly only the humble The memorabilia which form part Retorno de los exiliados / Return of the exiles needle, thread and scraps of fabric, of this exhibition are at first glance Chilean arpillera, Victoria Diaz ordinary everyday objects, yet the women worked individually or Caro, 1992, in groups, often in a clandestine stories they embody; the tangible, Photo Martin Melaugh manner at odd hours, in their tactile memories they store in Kinderhilfe arpillera collection, burning quest to present to the the folds of the people who wore Chile/Bonn world their experiences of conflict. -

Quality Library Services for People with Disabilities Ask

Issued by An Chomhairle Leabharlanna (The Library Council) No. 234 October 2003 ISSN 0332-0049 QUALITY LIBRARY SERVICES FOR ASK ABOUT IRELAND WEBSITE AND PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES OUR CULTURAL HERITAGE REPORT LAUNCHED The Equality Authority and An Chomhairle Leabharlanna launched Library Access at Dublin City Library and Archive, Pearse Street on 11th September. The publication examines how services within the library are best delivered in a manner that includes people with disabilities and provides new guidance to libraries on how to make reasonable accommodation for people with disabilities. The Minister of State at the Department of the Environment, Heritage and The Employment Equality Local Government, Mr. Pat “the Cope” Gallagher T.D., recently launched Act and the Equal Status the Ask About Ireland website www.askaboutireland.ie and the report Our Act require employers and L Cultural Heritage: A Strategy for Action for Public Libraries. service providers to Ask About Ireland is a showcase accommodate the needs of images of Irish heritage of people with disabilities. housed in the collections of local Service providers are libraries, museums and archives required to make reasonable changes in countrywide. Themed on the what they do and how they ‘Big House and Landed Estate do it, where without these Life in Ireland’, the site offers changes it would be very visitors a range of ways to difficult or impossible for explore Ireland’s colourful people with disabilities to history. The ‘Big House gain or remain in Experience’ is the interactive employment or obtain story of the rise and fall of the goods and services. -

AGM-Minutes-16-May-2019

The Linen Hall Library Minutes of the 230th Annual General Meeting on Thursday 16 May 2019 at 1pm Members in attendance: Ms Brigitte Anton, Mr S N Bridge, Ms Helen Broderick, Mr Sam Burnside, Mr Hugh Campbell, Ms Fionnuala Carson Williams, Mrs Alice Chapman OBE, Mr John Cross, Ms Dorothy Dunlop, Mr Ian J Forsythe, Dr R M Galloway, Mr John Gray, C T Hogg, Dr Eamonn Hughes, Mr W J Hunter, Mr John Johnston, Mr Gordon Lucy, Ms Lisa Maltman, Ms Noelle McCavana, Mr Christopher McCleane, Mr Rory McConnell (McConnell Chartered Surveyors Ltd), Mr Cliff Radcliffe, Mr John Roberts, Ms Nini Rodgers, Mr Oscar Ross, Mr Maolcholaim Scott, Ms Mary Ussher, Mr Barry Valentine 1. Apologies Apologies were received from Ms Karen Blair, Mr Peter Cavan, Judge Patrick Clyne, Prof James Stevens Curl; Mrs Anne Davies, Prof Simon Davies, Mrs Bernie Finan-Morgan, Mr Jack Johnston, Mr Wesley McCann, Mr Irvine McKay, Mr Eugene McKendry, Mr Jonathan Stewart 2. Minutes of the 229th Annual General Meeting (AGM) held on 17 May 2018 The 2018 AGM minutes were proposed by Mr Simon Bridge and seconded by Dr Eamonn Hughes 2.1 Matters arising There were no matters arising from the minutes. 3. Reports from the Library 3.1 President’s Address Mrs Alice Chapman OBE, President of the Board of Governors, opened the AGM and looked back at the Library’s 230th year: • She said that she had been honoured to serve the Linen Hall as President during a year which had seen many successes as well as challenges. • She congratulated the staff on the 2018 launch of the Divided Society digitisation project and looked forward to the new “Seen & Heard” digitisation project which was currently in its development phase. -

2016 Annual Report

AR Cover 2016_Layout 1 13/04/2017 12:20 Page 1 AR Cover 2016_Layout 1 13/04/2017 12:20 Page 3 The Linen Hall Library gratefully acknowledges the kind support of the following organisations: Cover photos (from top l-r): From the Presbyterian Orphan and Children’s Society: Generations of Generosity exhibition. Children taking part in the Creative Writing and Drama Project. Librarian Samantha McCombe welcoming the President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins, on the occasion of his visit to the Library in October. Annual Report 2016_Layout 1 13/04/2017 12:45 Page 1 Annual Report 2016_Layout 1 13/04/2017 12:45 Page 2 Children at Staging 2016 – the Library’s Creative Writing and Drama Project Annual Report 2016_Layout 1 13/04/2017 12:45 Page 3 Contents President’s Foreword Director’s Report Librarian’s Report Governors Staff & Volunteers 2016 Report Facts & Figures Financial Summary Statement of Financial Activities Statement of Financial Position Corporate Members Annual Report 2016_Layout 1 13/04/2017 12:46 Page 4 The Joys of Browsing from ‘Serenity in Landscape’ an exhibition by Sorrel Wills. Annual Report 2016_Layout 1 13/04/2017 12:46 Page 5 President’s Foreword From the financial report it is clear that the Library attracted significant sums of money to undertake important projects, such as Divided Society, which involves the digitisation of parts of our political collection; the Northern Ireland Literary Archive; and the popular Linen Hall cultural events programme. This is due to teamwork led by the Director and diligent management by the finance staff. Each application required strong ideas and subsequent attention to detail in the delivery of the projects, on time and within budgets. -

The Political Role of Northern Irish Protestant Religious Denominations

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work 2-1991 The Political Role of Northern Irish Protestant Religious Denominations Henry D. Fincher Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Fincher, Henry D., "The Political Role of Northern Irish Protestant Religious Denominations" (1991). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/68 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. - - - - - THE POtJ'TICAIJ I~OI~E OF NOR'TI-IERN IRISH - PROTESrrANrr REI~IGIOUS DENOMINATIONS - COLLEGE SCIIOLAR5,/TENNESSEE SCIIOLARS PROJECT - HENRY D. FINCHER ' - - FEnRlJARY IN, 1991 - - - .. - .. .. - Acknowledgements The completion of this project would have been impossible without assistance from many different individuals in the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Republic of Ireland. I appreciate the gifts of interviews from the MP's for South Belfast and South Wirral, respectively the Reverend Martin Smyth and the Honorable Barry Porter. Li kewi se, these in terv iews would have been impossible without the assistance of the Rt. Hon. Merlyn Rees MP PC, who arranged these two insightful contacts for me. In Belfast my research was aided enormously through the efforts of Mr. Robert Bell at the Linen Hall Library, as well as by the helpful and ever-cheerful librarians at the University of Ulster at Jordanstown. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: SLAVE SHIPS, SHAMROCKS, AND SHACKLES: TRANSATLANTIC CONNECTIONS IN BLACK AMERICAN AND NORTHERN IRISH WOMEN’S REVOLUTIONARY AUTO/BIOGRAPHICAL WRITING, 1960S-1990S Amy L. Washburn, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Dissertation directed by: Professor Deborah S. Rosenfelt Department of Women’s Studies This dissertation explores revolutionary women’s contributions to the anti-colonial civil rights movements of the United States and Northern Ireland from the late 1960s to the late 1990s. I connect the work of Black American and Northern Irish revolutionary women leaders/writers involved in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Black Panther Party (BPP), Black Liberation Army (BLA), the Republic for New Afrika (RNA), the Soledad Brothers’ Defense Committee, the Communist Party- USA (Che Lumumba Club), the Jericho Movement, People’s Democracy (PD), the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA), the Irish Republican Socialist Party (IRSP), the National H-Block/ Armagh Committee, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA), Women Against Imperialism (WAI), and/or Sinn Féin (SF), among others by examining their leadership roles, individual voices, and cultural productions. This project analyses political communiqués/ petitions, news coverage, prison files, personal letters, poetry and short prose, and memoirs of revolutionary Black American and Northern Irish women, all of whom were targeted, arrested, and imprisoned for their political activities. I highlight the personal correspondence, auto/biographical narratives, and poetry of the following key leaders/writers: Angela Y. Davis and Bernadette Devlin McAliskey; Assata Shakur and Margaretta D’Arcy; Ericka Huggins and Roseleen Walsh; Afeni Shakur-Davis, Joan Bird, Safiya Bukhari, and Martina Anderson, Ella O’Dwyer, and Mairéad Farrell. -

Decade of Anniversaries Toolkit

Understanding Our Past, SHAPING OUR FUTURE Introduction Contents This toolkit is developed as a resource for 1: What is Commemoration? 3 community and cultural groups, museums 2: How to Plan your own Decade of Anniversaries Project 5 and heritage, organisations, councils and departments, and other organisations who 3: Lessons and Tips for Ethical Commemorations 8 are considering commemorative projects or 4: Case Studies 12 1. 1912, A Hundred Years On 12 events in relation to what is popularly 2. 6th Connaught Rangers Research Group 13 3. An Inclusive Covenant 14 known as the ‘Decade of Centenaries.’ 4. Artsekta 15 5. Belfast City Council: Shared History – Different Allegiances, 1912-1914 16 In this toolkit, however, we Community Relations Council projects to have guidance and 6. Border Arts 17 have chosen to use the term and the Heritage Lottery Fund support in acts of 7. Causeway Museum Services 18 ‘Decade of Anniversaries’. The that commemorations of events commemoration. The ‘how to 8. Connection & Division: 1910-1930 19 reason for this is a simple one: from the distant as well as plan your own’ section goes 9. Cultural Fusions 20 while there is currently a strong recent past have drawn through questions and issues 10.Ethical & Shared Remembering 21 emphasis on centenary events, significant attention in this that need to be considered 11.The Fellowship of Messines Association 22 not everything being decade as well; and these are when putting together a commemorated in our society worth considering in the programme or event and the 12.Home Rule? 23 today happened exactly 100 context of discussing how to ‘key findings’ detail lessons 13.The Junction: Laura Gailey Film 24 years ago, and those events did commemorate in a way that learned as seen in the case 14.Maiden’s City: A ‘Herstory’ Tour of the Walled City 25 not take place in a time vacuum unites rather than divides studies. -

The IRA's Hunger Game: Game Theory, Political Bargaining and the Management of the 1980-1981 Hunger Strikes in Northern Ireland

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons CUREJ - College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal College of Arts and Sciences 4-2012 The IRA's Hunger Game: Game Theory, Political Bargaining and the Management of the 1980-1981 Hunger Strikes in Northern Ireland Meghan M. Hussey University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Hussey, Meghan M., "The IRA's Hunger Game: Game Theory, Political Bargaining and the Management of the 1980-1981 Hunger Strikes in Northern Ireland" 01 April 2012. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania, https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/154. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/154 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The IRA's Hunger Game: Game Theory, Political Bargaining and the Management of the 1980-1981 Hunger Strikes in Northern Ireland Keywords IRA, Northern Ireland, prisons, game theory, hunger strike, political science, ethnic conflict, Ireland, Great Britain, political bargaining, Social Sciences, Political Science, Brendan O'Leary, O'Leary, Brendan Disciplines Political Science This article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/154 The IRA’s Hunger Game: Game Theory, Political Bargaining and the Management of the 1980-1981 Hunger Strikes in Northern Ireland By, Meghan M. Hussey Advised by: Dr. Brendan O’Leary A Senior Honors Thesis in Political Science The University of Pennsylvania 2012 Acknowledgements I would like to make several acknowledgements of those without which this thesis would not have been possible. First and foremost I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. -

Annual Report 2018

www.linenhall.com Took a wee break from the intensity of #wesconf18 to visit the 230-yr-old #LinenhallLibrary - highly recommended if you want some peace & access to a feast of Northern Irish culture & polical history. @thelinenhall Alice Rose @DrAliceCorble The Linen Hall Library gratefully acknowledges the kind support of the following organisations: Cover Photos (from top): LHL Director Julie Andrews. Acclaimed journalist Kate Adie OBE launches new Divided Society digital archive. From Belfast PerspectivesExhibition by Kevin Hamilton Contents We connue to share photos of libraries around the world visited by WPL staffers. This week it's the grand-looking entrance to the @thelinenhall in #Belfast #NorthernIreland The library, one of the oldest in the United Kingdom, was established 1788. #traveltuesday #librarylove Waterloo Library @WaterlooLibrary President’s Foreword 01 Director’s Report 01 Librarian’s Report 03 Governors 04 Staff & Volunteers 05 2018 Report 06 Facts & Figures 12 Financial Summary 13 Statement of Financial Activities 14 Statement of Financial Position 15 Corporate Members 16 From Stickin Out Sketches of BelfastExhibition by Geordie Morrow President’s Foreword Imagine a haven of respite, cultural restoration and rejuvenation right in the centre of Belfast. What could be more enjoyable than to be performing the function of President for this gem? The Linen Hall Library has continued to deliver a menu of stimulating ntseve throughout the past year which represent a range of arts, cultural and tourist programmes. From exhibitions in our public spaces to the hiring of rooms for drama, poetry and literacy, we have continued to thrive throughout the year. Mindful of meeting the expectations of our loyal members, as well as owcasingsh to the general public, I am immensely proud of the achievements of the Director and the staff of the Linen Hall. -

Libraries & Turbulence

University of Kentucky From the SelectedWorks of Lauren E. Robinson Winter 2018 Libraries & Turbulence: Poster Art During Social and Political Unrest Lauren E Robinson Available at: https://works.bepress.com/lauren_robinson/7/ FEATURE K ENTUCKY L IBRARY A SSOCIATION Libraries & Turbulence Poster Art during Social and Political Unrest BY LAUREN ROBINSON EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES LIBRARIAN KORNHAUSER HEALTH SCIENCES LIBRARY 14 UNIVERSITY OF LOUISVILLE Posters adorn the walls of our streets, reflect our environment, The societal revolutions and social activism of twentieth-century color our imagination, shape our ideologies, channel dreams, America utilized posters as a form of communication for the disen- excite desires, illustrate harsh realities, and can offer a voice to franchised, and often commented on political corruption, societal the voiceless. Posters communicate the principles and undercur- inequalities, and the growth of economic inequity. Poster art was rents that shape and govern a society due to their inherently often “the catalyst or precursor” to these significant political and cheap and mobile nature. The indispensable lesson posters offer social changes (Cowick 29). is not in their overt message, but in what they depict about a society, its cultural and social issues. Poster art can provide a unique glimpse into the psyche of people living through political and social upheaval. Posters can define generations, cross ethnic and sectarian lines, transcend literacy boundaries, and perhaps ultimately give viewers a different perspective of their own societies. Political and social history were mirrored in the posters lining the streets during the French Revolution, the Nazi occupation of France, the Cultural Revolution in China, the American Civil Rights Movement, the Kent State Vietnam War Protest, the Arab Spring, and countless other periods of social unrest. -

An Leabharlann the Irish Library Volume:15

An ≠eabharlann THE IRISH LIBRARY Second Series Volume 15 Number 3⁄4 2001 * Design History and Material Culture in Ireland * Magee Collection in St. Mary’s University College Library * The Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich Memorial Library and Archive * The Deral Project *News * Reviews An ≠eabharlann THE IRISH LIBRARY ISSN 0023-9542 Second Series Volume 15 Number 3⁄4 2001 CONTENTS PAGE Design History and Material Culture in Ireland: An outline of sources and resources Paul Caffrey 119 Magee Collection in St Mary’s University College Library Sheila Fitzpatrick 124 The Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich Memorial Library and Archive Crónán Ó Doibhlin 131 The Deral Project Mary Shapcott and Adrian Moore 136 Interview: Helen Osborn 146 New Appointment: Elaine Urquhart 149 Information Matters: News and Notes 150 Reviews l Libraries and the Visually Impaired Margaret Smyth 161 l Dictionary of Ulster Place Names Crónán Ó Doibhlin 162 An ≠eabharlann THE IRISH LIBRARY Journal of the Library Association of Ireland and the Northern Ireland Branch of the Library Association Editors: Pat McMahon and Mary Kintner Associate Editor: Crónán Ó Doibhlin • This issue edited by Mary Kintner Prospective manuscripts for inclusion in the journal should be sent to: * Pat McMahon, Galway County Library, Island House, Cathedral Square, Galway, Republic of Ireland. Fax: +353 91 565039. Email : [email protected] * Mary Kintner, Rathcoole Branch Library, 2 Rosslea Way, Rathcoole bt37 9bj. N. Ireland. Fax: 028 90 851157. Email: [email protected] Books for review should be sent to: * Crónán Ó Doibhlin, Cardinal Ó Fiaich Memorial Library and Archive, 15 Moy Road, Armagh, bt61 7ly, Fax: o28 375 11944. -

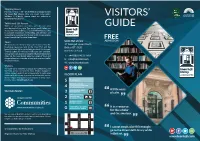

Linen Hall Library-Visitors Guide Leaflets-Final Hi-Res.Qxp 04/10/2019 10:43 Page 1

Linen Hall Library-Visitors Guide Leaflets-Final Hi-res.qxp 04/10/2019 10:43 Page 1 Opening Hours Monday – Friday: 9.30 – 17.30 There is no charge to enter the Linen Hall Library. (We are closed most public holidays. If in doubt, please check our website or VISITORS’ telephone the Library.) Toilets and Lift Access Toilets are available to members and café users who GUIDE provide proof of purchase. The nearest public toilets are across the street in Belfast City Hall. Wheelchair access is available throughout the building, and all floors are accessible by customer lift. To avail of lift access, please enter through the Fountain Street door. Linen Hall Library Tours A Library tour is the best way to be introduced to the 17 Donegall Square North invaluable resources held in the Linen Hall and the Belfast BT1 5GB beautiful listed Victorian building in which it is housed. Northern Ireland There is a short 45- minute introductory tour available. Group tours can also be arranged. Advanced booking is required. For more details about our range of tours and T: +44 (0)28 9032 1707 charges please ask a member of staff, pick up a tour leaflet, E: [email protected] or visit our website. W: www.linenhall.com Visitors All visitors are welcome to access our collections, and staff are always on hand to help. Visitors engaged in serious research projects are recommended to make prior contact with the Library to ensure the best possible service. FLOOR PLAN Some charges may apply. Contact Library staff for more information at [email protected].