Environmental Impacts of Classical Biological Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Squash Bug, Anasa Tristis (Degeer)1

Archival copy: for current recommendations see http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu or your local extension office. EENY-077 Squash Bug, Anasa tristis (DeGeer)1 John L. Capinera2 Introduction Egg The squash bug, Anasa tristis, attacks cucurbits Eggs are deposited on the lower surface of (squash and relatives) throughout Central America, leaves, though occasionally they occur on the upper the United States, and southern Canada. Several surface or on leaf petioles. The elliptical egg is related species in the same genus coexist with squash somewhat flattened and bronze in color. The average bug over most of its range, feeding on the same plants egg length is about 1.5 mm and the width about 1.1 but causing much less injury. mm. Females deposit about 20 eggs in each egg cluster. Eggs may be tightly clustered (Figure 1) or Life Cycle spread a considerable distance apart, but an equidistant spacing arrangement is commonly The complete life cycle of squash bug commonly observed. Duration of the egg stage is about seven to requires six to eight weeks. Squash bugs have one nine days. generation per year in northern climates and two to three generations per year in warmer regions. In Nymph intermediate latitudes the early-emerging adults from the first generation produce a second generation There are five nymphal instars. The nymphal whereas the late-emerging adults go into diapause. stage requires about 33 days for complete Both sexes overwinter as adults. The preferred development. The nymph is about 2.5 mm in length overwintering site seems to be in cucurbit fields when it hatches, and light green in color. -

Twenty-Five Pests You Don't Want in Your Garden

Twenty-five Pests You Don’t Want in Your Garden Prepared by the PA IPM Program J. Kenneth Long, Jr. PA IPM Program Assistant (717) 772-5227 [email protected] Pest Pest Sheet Aphid 1 Asparagus Beetle 2 Bean Leaf Beetle 3 Cabbage Looper 4 Cabbage Maggot 5 Colorado Potato Beetle 6 Corn Earworm (Tomato Fruitworm) 7 Cutworm 8 Diamondback Moth 9 European Corn Borer 10 Flea Beetle 11 Imported Cabbageworm 12 Japanese Beetle 13 Mexican Bean Beetle 14 Northern Corn Rootworm 15 Potato Leafhopper 16 Slug 17 Spotted Cucumber Beetle (Southern Corn Rootworm) 18 Squash Bug 19 Squash Vine Borer 20 Stink Bug 21 Striped Cucumber Beetle 22 Tarnished Plant Bug 23 Tomato Hornworm 24 Wireworm 25 PA IPM Program Pest Sheet 1 Aphids Many species (Homoptera: Aphididae) (Origin: Native) Insect Description: 1 Adults: About /8” long; soft-bodied; light to dark green; may be winged or wingless. Cornicles, paired tubular structures on abdomen, are helpful in identification. Nymph: Daughters are born alive contain- ing partly formed daughters inside their bodies. (See life history below). Soybean Aphids Eggs: Laid in protected places only near the end of the growing season. Primary Host: Many vegetable crops. Life History: Females lay eggs near the end Damage: Adults and immatures suck sap from of the growing season in protected places on plants, reducing vigor and growth of plant. host plants. In spring, plump “stem Produce “honeydew” (sticky liquid) on which a mothers” emerge from these eggs, and give black fungus can grow. live birth to daughters, and theygive birth Management: Hide under leaves. -

Establishment of Parasites to Control Ne2ara Viridula Variety Smaragdula (Fabricius) in Hawaii (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae)

Vol. XVIII, No. 3, June, 1964 369 The Introduction, Propagation, Liberation, and Establishment of Parasites to Control Ne2ara viridula variety smaragdula (Fabricius) in Hawaii (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) C. J. Davis STATE DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE HONOLULU, HAWAII {Presidential Address delivered at the meeting of December 9, 1963) INTRODUCTION A serious pest of fruits, nuts, vegetables and ornamentals, the southern green stink bug, Nezara viridula smaragdula (Fabricius),1 was discovered on the University of Hawaii Farm, Honolulu, in October 1961. Despite cooperative eradication efforts by University of Hawaii and State Department of Agriculture entomologists, it became widespread on Oahu and, by August 1963, had appeared on all major neighbor islands. The build-up of large stink bug populations in Hawaii was undoubtedly aided by favorable climatic conditions, lack of natural enemies, and the availability of preferential wild weed hosts such as Asystasia coromandeliana: cheese weed, Malva parviflora; Crotalaria spp.; castor bean, Ricinus communis; black nightshade or popolo, Solanu??i nigrum; Amaranthus spp.; wild spider flower, Gynandropsis gynandra, and garden crops, particularly soybean, Glycine sp. and string bean, Phaseolus sp. All are nearly ubiquitous in the lowland areas and sustain all stages of the stink bug. Since chemical control was limited by the lack of an effective residual insecticide, and since well-known enemies of the stink bug were known to occur in Australia and the West Indies, arrangements were made with these countries to send parasites. Beginning December 1961, 10 shipments of the egg parasites Telenomus basalis Wollaston, Xenoencyrtus nigerRiek, and Telenomus sp. were received from Australia through the courtesy of Dr. Douglas Waterhouse. -

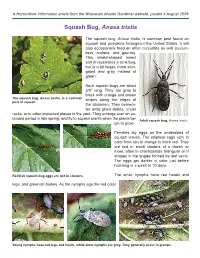

Squash Bug, Anasa Tristis

A Horticulture Information article from the Wisconsin Master Gardener website, posted 4 August 2008 Squash Bug, Anasa tristis The squash bug, Anasa tristis, is common pest found on squash and pumpkins throughout the United States. It will also occasionally feed on other curcurbits as well (cucum- bers, melons, and gourds). This shield-shaped insect sort of resembles a stink bug, but is a bit larger, more elon- gated and gray instead of green. Adult squash bugs are about 5/8” long. They are gray to black with orange and brown The squash bug, Anasa tristis, is a common stripes along the edges of pest of squash. the abdomen. They overwin- ter amid plant debris, under rocks, or in other protected places in the yard. They emerge over an ex- tended period in late spring, and fl y to squash plants when the plants be- Adult squash bug, Anasa tristis. gin to grow. Females lay eggs on the undersides of squash leaves. The elliptical eggs vary in color from tan to orange to brick red. They are laid in small clusters of a dozen or more, often in characteristic triangular or V shapes in the angles formed by leaf veins. The eggs get darker in color just before hatching in a week to 10 days. Reddish squash bug eggs are laid in clusters. The small nymphs have red heads and legs, and greenish bodies. As the nymphs age the red color Young nymphs have red legs and heads, while older nymphs are grey. They generally occur in groups. turns to black, and the older ones look like they are covered with a grainy gray powder. -

Chapter 12. Estimating the Host Range of the Tachinid Trichopoda Giacomellii, Introduced Into Australia for Biological Control of the Green Vegetable Bug

__________________________________ ASSESSING HOST RANGES OF PARASITOIDS AND PREDATORS CHAPTER 12. ESTIMATING THE HOST RANGE OF THE TACHINID TRICHOPODA GIACOMELLII, INTRODUCED INTO AUSTRALIA FOR BIOLOGICAL CONTROL OF THE GREEN VEGETABLE BUG M. Coombs CSIRO Entomology, 120 Meiers Road, Indooroopilly, Queensland, Australia 4068 [email protected] BACKGROUND DESCRIPTION OF PEST INVASION AND PROBLEM Nezara viridula (L.) is a cosmopolitan pest of fruit, vegetables, and field crops (Todd, 1989). The native geographic range of N. viridula is thought to include Ethiopia, southern Europe, and the Mediterranean region (Hokkanen, 1986; Jones, 1988). Other species in the genus occur in Africa and Asia (Freeman, 1940). First recorded in Australia in 1916, N. viridula soon be- came a widespread and serious pest of most legume crops, curcubits, potatoes, tomatoes, pas- sion fruit, sorghum, sunflower, tobacco, maize, crucifers, spinach, grapes, citrus, rice, and mac- adamia nuts (Hely et al., 1982; Waterhouse and Norris, 1987). In northern Victoria, central New South Wales, and southern Queensland, N. viridula is a serious pest of soybeans and pecans (Clarke, 1992; Coombs, 2000). Immature and adult bugs feed on vegetative buds, devel- oping and mature fruits, and seeds, causing reductions in crop quality and yield. The pest status of N. viridula in Australia is assumed to be partly due to the absence of parasitoids of the nymphs and adults. No native Australian tachinids have been found to parasitize N viridula effectively, although occasional oviposition and development of some species may occur (Cantrell, 1984; Coombs and Khan, 1997). Previous introductions of biological control agents to Australia for control of N. viridula include Trichopoda pennipes (Fabricius) and Trichopoda pilipes (Fabricius) (Diptera: Tachinidae), which are important parasitoids of N. -

E0020 Common Beneficial Arthropods Found in Field Crops

Common Beneficial Arthropods Found in Field Crops There are hundreds of species of insects and spi- mon in fields that have not been sprayed for ders that attack arthropod pests found in cotton, pests. When scouting, be aware that assassin bugs corn, soybeans, and other field crops. This publi- can deliver a painful bite. cation presents a few common and representative examples. With few exceptions, these beneficial Description and Biology arthropods are native and common in the south- The most common species of assassin bugs ern United States. The cumulative value of insect found in row crops (e.g., Zelus species) are one- predators and parasitoids should not be underes- half to three-fourths of an inch long and have an timated, and this publication does not address elongate head that is often cocked slightly important diseases that also attack insect and upward. A long beak originates from the front of mite pests. Without biological control, many pest the head and curves under the body. Most range populations would routinely reach epidemic lev- in color from light brownish-green to dark els in field crops. Insecticide applications typical- brown. Periodically, the adult female lays cylin- ly reduce populations of beneficial insects, often drical brown eggs in clusters. Nymphs are wing- resulting in secondary pest outbreaks. For this less and smaller than adults but otherwise simi- reason, you should use insecticides only when lar in appearance. Assassin bugs can easily be pest populations cannot be controlled with natu- confused with damsel bugs, but damsel bugs are ral and biological control agents. -

Egg Viability and Larval Penetration in Trichopoda Pennipes Pilipes Mohammad Shahjahan2 and John W. Beardsley, Jr.3 Trichopoda P

Vol. XXII, No. 1, August, 1975 '33 Egg Viability and Larval Penetration in Trichopoda pennipes pilipes Fabricius (Diptera: Tachinidae)1 Mohammad Shahjahan2 and John W. Beardsley, Jr.3 Trichopoda pennipes pilipes Fabricius was introduced into Hawaii from Trinidad in 1962 to combat the southern green stink bug, Nezara viridula (Fabricius) (Davis and Krauss, 1963; Davis, 1964). In Hawaii, T. p. pilipes has been reared from the scutellerid Coleotichus blackburni White and the pentatomids Thyanta accera (McAtee) and Plautia stali Scott, in addition to N. viridula. During 1965 we began a study on the biology of T. p. pilipes in rela tion to its principal host in Hawaii, N. viridula. Laboratory experiments and observations were conducted to evaluate the effects of superparasiti- zation of N. viridula by the tachinid on both the host and parasite pop ulations. The results of some of this work were reported previously (Shahjahan, 1968). The present paper summarizes data which were ob tained on parasite egg viability and larval penetration of host integument. The methods used in rearing and handling both N. viridula and T. p. pilipes were described in the earlier paper (Shahjahan, 1968). Supernumerary Oviposition and Egg Viability Adults of the southern green stink bug often are heavily superpara- sitized by T. p. pilipes, both in the field and under laboratory conditions. As many as 237 T. p. pilipes eggs were counted on a single field-collected stink bug, and a high of 275 eggs were deposited on one bug in the lab oratory (Shahjahan, 1968). Eggs are placed predominantly on the venter of the thorax, but may be deposited on almost any part of the host, in cluding the appendages, wings, eyes, etc. -

Diptera : Tachinidae) in Western Switzerland

First detection of the southern green stink bug parasitoid Trichopoda pennipes (Fabr.) (Diptera : Tachinidae) in Western Switzerland Autor(en): Pétremand, Gaël / Rochefort, Sophie / Jaccard, Gaëtan Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Mitteilungen der Schweizerischen Entomologischen Gesellschaft = Bulletin de la Société Entomologique Suisse = Journal of the Swiss Entomological Society Band (Jahr): 88 (2015) Heft 3-4 PDF erstellt am: 23.09.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-583862 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. -

Study of a Possibly New Ecuadorian Trichopoda Berthold Species

Study of a possibly new Ecuadorian Trichopoda Berthold species (Diptera: Tachinidae) by Roberto Andreocci Dipartimento di Biologia e Biotecnologie “Charles Darwin”, Sapienza Università di Roma, Piazzale A. Moro 5, 00185, Rome, Italy. E-mail: [email protected] while pursuing an undergrad degree in Natural Sciences at Sapienza University in I became interested in flies Rome. One of my courses was taught by dipterist Pierfilippo Cerretti, who is well known for his systematic research on Tachinidae and related families. Under his encouragement and supervision I undertook an undergrad thesis on the Rhinophoridae that I completed in the summer of 2018. During my undergrad studies I heard about Diego Inclàn, a former Master’s student with John Stireman at Wright State University in the United States and former Ph.D. student with Pierfilippo at Padova University in northern Italy. Diego studied tachinid flies for both degrees and returned to his native country of Ecuador with a background in both systematic and ecological research. He is now the Director of the Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad (INABIO, http://www.biodiversidad.gob.ec/) and a professor at the Universidad Central del Ecuador in Quito. In addition to his other duties, Diego oversees a growing collection of Ecuadorian tachinids originating from some of the most biologically diverse areas of Ecuador, from the lowland rainforests of the Chocó region to the high elevation grasslands of the Andean páramo. I contacted Diego about opportunities for graduate research on Tachinidae and he told me about a potential project involving an unstudied host-parasitoid association in Ecuador. He had stumbled upon some iNaturalist observations near Quito of a leaf-footed bug, Leptoglossus zonatus (Dallas) (Hemiptera: Coreidae), with tachinid eggs on an antenna (Fig. -

Beneficial Insects of Utah Guide

BENEFICIAL INSECTS OF UTAH beneficial insects & other natural enemies identification guide PUBLICATION COORDINATORS AND EDITORS Cami Cannon (Vegetable IPM Associate and Graphic Design) Marion Murray (IPM Project Leader) AUTHORS Cami Cannon Marion Murray Ron Patterson (insects: ambush bug, collops beetle, red velvet mite) Katie Wagner (insects: Trichogramma wasp) IMAGE CREDITS All images are provided by Utah State University Extension unless otherwise noted within the image caption. CONTACT INFORMATION Utah State University IPM Program Dept. of Biology 5305 Old Main Hill Logan, UT 84322 (435) 797-0776 utahpests.usu.edu/IPM FUNDING FOR THIS PUBLICATION WAS PROVIDED BY: USU Extension Grants Program CONTENTS PREFACE Purpose of this Guide ................................................................6 Importance of Natural Enemies ..................................................6 General Practices to Enhance Natural Enemies ...........................7 Plants that will Enhance Natural Enemy Populations ..................7 PREDATORS Beetles .....................................................................................10 Flies .........................................................................................24 Lacewings/Dustywings .............................................................32 Mites ........................................................................................36 Spiders .....................................................................................42 Thrips ......................................................................................44 -

The Tachinid Times

The Tachinid Times ISSUE 24 February 2011 Jim O’Hara, editor Invertebrate Biodiversity Agriculture & Agri-Food Canada ISSN 1925-3435 (Print) C.E.F., Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1A 0C6 ISSN 1925-3443 (Online) Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] My thanks to all who have contributed to this year’s announcement before the end of January 2012. This news- issue of The Tachinid Times. This is the largest issue of the letter accepts submissions on all aspects of tachinid biology newsletter since it began in 1988, so there still seems to be and systematics, but please keep in mind that this is not a a place between peer-reviewed journals and Internet blogs peer-reviewed journal and is mainly intended for shorter for a medium of this sort. This year’s issue has a diverse news items that are of special interest to persons involved assortment of articles, a few announcements, a listing of in tachinid research. Student submissions are particularly recent literature, and a mailing list of subscribers. The welcome, especially abstracts of theses and accounts of Announcements section is more sizable this year than usual studies in progress or about to begin. I encourage authors and I would like to encourage readers to contribute to this to illustrate their articles with colour images, since these section in the future. This year it reproduces the abstracts add to the visual appeal of the newsletter and are easily of two recent theses (one a Ph.D. and the other a M.Sc.), incorporated into the final PDF document. -

Diptera: Tachinidae) for Efficacy and Non-Target Effects M

____________ Post-release evaluation of Trichopoda giacomellii for efficacy and non-target effects 399 POST-RELEASE EVALUATION OF TRICHOPODA GIACOMELLII (DIPTERA: TACHINIDAE) FOR EFFICACY AND NON-TARGET EFFECTS M. Coombs Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, Entomology, Long Pocket Laboratories, Indooroopilly, Queensland, Australia INTRODUCTION The tachinid parasitoid Trichopoda giacomellii (Blanchard) was approved for release in Australia in 1996 following quarantine evaluation as a biological control agent for Nezara viridula (L.) (Hemi- ptera: Pentatomidae) (Sands and Coombs, 1999). Release and establishment studies were completed in 1999 with establishment centered on a 1,400 acre pecan orchard located at Moree in western New South Wales, Australia (Coombs and Sands, 2000). The target pest N. viridula, as in other parts of the world, attacks a wide range of horticultural and agricultural crops in Australia (Waterhouse, 1998). The primary means of control of N. viridula has remained primarily the use of pesticides either indi- rectly from sprays targeting other pests (most often Helicoverpa spp.) or less often applied as a direct control, as was the situation in pecans (Seymour and Sands, 1993). Previous attempts at classical biological control of N. viridula in Australia have included the introduction of several egg parasitoids (primarily scelionid parasitoids of the genus Trissolcus) and tachinid parasitoids attacking adult bugs (Bogosia antinorii Rondani, Trichopoda pilipes [Fabricius], and Trichopoda pennipes [Fabricius]) (Waterhouse, 1998; Waterhouse and Sands, 2001). Whereas Trissolcus basalis (Wollaston) has proved effective in reducing N. viridula populations over parts of the pest’s range in Australia, none of the tachinid species established. Because N. viridula has re- mained a significant pest in Australia, I studied the tachinid T.