Squash Bug, Anasa Tristis (Degeer)1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Twenty-Five Pests You Don't Want in Your Garden

Twenty-five Pests You Don’t Want in Your Garden Prepared by the PA IPM Program J. Kenneth Long, Jr. PA IPM Program Assistant (717) 772-5227 [email protected] Pest Pest Sheet Aphid 1 Asparagus Beetle 2 Bean Leaf Beetle 3 Cabbage Looper 4 Cabbage Maggot 5 Colorado Potato Beetle 6 Corn Earworm (Tomato Fruitworm) 7 Cutworm 8 Diamondback Moth 9 European Corn Borer 10 Flea Beetle 11 Imported Cabbageworm 12 Japanese Beetle 13 Mexican Bean Beetle 14 Northern Corn Rootworm 15 Potato Leafhopper 16 Slug 17 Spotted Cucumber Beetle (Southern Corn Rootworm) 18 Squash Bug 19 Squash Vine Borer 20 Stink Bug 21 Striped Cucumber Beetle 22 Tarnished Plant Bug 23 Tomato Hornworm 24 Wireworm 25 PA IPM Program Pest Sheet 1 Aphids Many species (Homoptera: Aphididae) (Origin: Native) Insect Description: 1 Adults: About /8” long; soft-bodied; light to dark green; may be winged or wingless. Cornicles, paired tubular structures on abdomen, are helpful in identification. Nymph: Daughters are born alive contain- ing partly formed daughters inside their bodies. (See life history below). Soybean Aphids Eggs: Laid in protected places only near the end of the growing season. Primary Host: Many vegetable crops. Life History: Females lay eggs near the end Damage: Adults and immatures suck sap from of the growing season in protected places on plants, reducing vigor and growth of plant. host plants. In spring, plump “stem Produce “honeydew” (sticky liquid) on which a mothers” emerge from these eggs, and give black fungus can grow. live birth to daughters, and theygive birth Management: Hide under leaves. -

Organic Options for Striped Cucumber Beetle Management in Cucumbers Katie Brandt Grand Valley State University

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Masters Theses Graduate Research and Creative Practice 6-2012 Organic Options for Striped Cucumber Beetle Management in Cucumbers Katie Brandt Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Brandt, Katie, "Organic Options for Striped Cucumber Beetle Management in Cucumbers" (2012). Masters Theses. 29. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses/29 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research and Creative Practice at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ORGANIC OPTIONS FOR STRIPED CUCUMBER BEETLE MANAGEMENT IN CUCUMBERS Katie Brandt A thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of GRAND VALLEY STATE UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Biology June 2012 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to my advisors, who helped me plan this research and understand the interactions of beetles, plants and disease in this system. Jim Dunn helped immensely with the experimental design and prevented me from giving up when my replication block was destroyed in a flood. Mathieu Ngouajio generously shared his expertise with organic vegetables, field trials and striped cucumber beetles. Mel Northup lent the HOBO weather stations, visited the farm to instruct me to set them up and later transferred the data into an Excel spreadsheet. Sango Otieno and the students at the Statistical Consulting Center at GVSU were very helpful with data analysis. Numerous farmworkers and volunteers also helped in the labor-intensive process of gathering data for this research. -

Squash Bug, Anasa Tristis (Degeer)

CHARACTERIZING THE OVERWINTERING AND El\ffiRGENCE BERAVIORS OF THE ADULT SQUASH BUG, ANASA TRISTIS (DEGEER) By JESSE ALAN EIBEN Bachelor of Science in Psychobiology Albright College Reading, PA 2001 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December, 2004 CHARACTERIZING THE OVERWINTERING AND EMERGENCE BEHAVIORS OF THE ADULT SQUASH BUG, ANASA TRISTIS (DEGEER) Thesis Approved: I Thesis Advisor 7Dean of the Graduate College ii PREFACE Research was conducted from 2002 to 2004 at the Wes Watkins Agricultural Research and Extension Center (WWAREC) in Lane, Oklahoma to illuminate the specific behaviors of adult overwintering squash bugs during the winter hibernating period and during their spring emergence. These studies were conducted in the field with the adult squash bug, Anasa tristis (Degeer), its host plant the yellow crook-necked squash, Cucurbita pepo 'lemondrop', and its overwintering habitats consisting of many sheltering objects found in the ecological landscape. The first chapter is introductory and the last two chapters present results as complete manuscripts to be submitted to scientific journals following manuscript guidelines established by the Entomological Society of America. I would like to acknowledge the following people for valuable advice and assistance throughout my research endeavors at OSU. My sincerest thanks go to my major advisor Dr. Jonathan Edelson. He has given me this wonderful opportunity and the freedom to pursue a project that was both wide in berth and exploratory in nature. The other members of my graduate committee, Dr. Kris Giles, Dr. Thomas Phillips, and Dr. -

Establishment of Parasites to Control Ne2ara Viridula Variety Smaragdula (Fabricius) in Hawaii (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae)

Vol. XVIII, No. 3, June, 1964 369 The Introduction, Propagation, Liberation, and Establishment of Parasites to Control Ne2ara viridula variety smaragdula (Fabricius) in Hawaii (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) C. J. Davis STATE DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE HONOLULU, HAWAII {Presidential Address delivered at the meeting of December 9, 1963) INTRODUCTION A serious pest of fruits, nuts, vegetables and ornamentals, the southern green stink bug, Nezara viridula smaragdula (Fabricius),1 was discovered on the University of Hawaii Farm, Honolulu, in October 1961. Despite cooperative eradication efforts by University of Hawaii and State Department of Agriculture entomologists, it became widespread on Oahu and, by August 1963, had appeared on all major neighbor islands. The build-up of large stink bug populations in Hawaii was undoubtedly aided by favorable climatic conditions, lack of natural enemies, and the availability of preferential wild weed hosts such as Asystasia coromandeliana: cheese weed, Malva parviflora; Crotalaria spp.; castor bean, Ricinus communis; black nightshade or popolo, Solanu??i nigrum; Amaranthus spp.; wild spider flower, Gynandropsis gynandra, and garden crops, particularly soybean, Glycine sp. and string bean, Phaseolus sp. All are nearly ubiquitous in the lowland areas and sustain all stages of the stink bug. Since chemical control was limited by the lack of an effective residual insecticide, and since well-known enemies of the stink bug were known to occur in Australia and the West Indies, arrangements were made with these countries to send parasites. Beginning December 1961, 10 shipments of the egg parasites Telenomus basalis Wollaston, Xenoencyrtus nigerRiek, and Telenomus sp. were received from Australia through the courtesy of Dr. Douglas Waterhouse. -

Squash Bug, Anasa Tristis

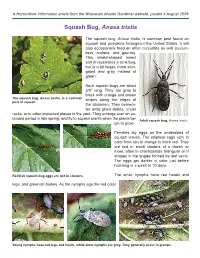

A Horticulture Information article from the Wisconsin Master Gardener website, posted 4 August 2008 Squash Bug, Anasa tristis The squash bug, Anasa tristis, is common pest found on squash and pumpkins throughout the United States. It will also occasionally feed on other curcurbits as well (cucum- bers, melons, and gourds). This shield-shaped insect sort of resembles a stink bug, but is a bit larger, more elon- gated and gray instead of green. Adult squash bugs are about 5/8” long. They are gray to black with orange and brown The squash bug, Anasa tristis, is a common stripes along the edges of pest of squash. the abdomen. They overwin- ter amid plant debris, under rocks, or in other protected places in the yard. They emerge over an ex- tended period in late spring, and fl y to squash plants when the plants be- Adult squash bug, Anasa tristis. gin to grow. Females lay eggs on the undersides of squash leaves. The elliptical eggs vary in color from tan to orange to brick red. They are laid in small clusters of a dozen or more, often in characteristic triangular or V shapes in the angles formed by leaf veins. The eggs get darker in color just before hatching in a week to 10 days. Reddish squash bug eggs are laid in clusters. The small nymphs have red heads and legs, and greenish bodies. As the nymphs age the red color Young nymphs have red legs and heads, while older nymphs are grey. They generally occur in groups. turns to black, and the older ones look like they are covered with a grainy gray powder. -

Chapter 12. Estimating the Host Range of the Tachinid Trichopoda Giacomellii, Introduced Into Australia for Biological Control of the Green Vegetable Bug

__________________________________ ASSESSING HOST RANGES OF PARASITOIDS AND PREDATORS CHAPTER 12. ESTIMATING THE HOST RANGE OF THE TACHINID TRICHOPODA GIACOMELLII, INTRODUCED INTO AUSTRALIA FOR BIOLOGICAL CONTROL OF THE GREEN VEGETABLE BUG M. Coombs CSIRO Entomology, 120 Meiers Road, Indooroopilly, Queensland, Australia 4068 [email protected] BACKGROUND DESCRIPTION OF PEST INVASION AND PROBLEM Nezara viridula (L.) is a cosmopolitan pest of fruit, vegetables, and field crops (Todd, 1989). The native geographic range of N. viridula is thought to include Ethiopia, southern Europe, and the Mediterranean region (Hokkanen, 1986; Jones, 1988). Other species in the genus occur in Africa and Asia (Freeman, 1940). First recorded in Australia in 1916, N. viridula soon be- came a widespread and serious pest of most legume crops, curcubits, potatoes, tomatoes, pas- sion fruit, sorghum, sunflower, tobacco, maize, crucifers, spinach, grapes, citrus, rice, and mac- adamia nuts (Hely et al., 1982; Waterhouse and Norris, 1987). In northern Victoria, central New South Wales, and southern Queensland, N. viridula is a serious pest of soybeans and pecans (Clarke, 1992; Coombs, 2000). Immature and adult bugs feed on vegetative buds, devel- oping and mature fruits, and seeds, causing reductions in crop quality and yield. The pest status of N. viridula in Australia is assumed to be partly due to the absence of parasitoids of the nymphs and adults. No native Australian tachinids have been found to parasitize N viridula effectively, although occasional oviposition and development of some species may occur (Cantrell, 1984; Coombs and Khan, 1997). Previous introductions of biological control agents to Australia for control of N. viridula include Trichopoda pennipes (Fabricius) and Trichopoda pilipes (Fabricius) (Diptera: Tachinidae), which are important parasitoids of N. -

Anasa Tristis) Can Be a Serious Insect Pest for Organic Summer Squash Growers

EFFECTS OF COVER CROPS AND ORGANIC INSECTICIDES ON SQUASH BUG (ANASA TRISTIS) POPULATIONS by LINDSAY NICHOLE DAVIES (Under the Direction of David Berle) ABSTRACT Squash bugs (Anasa tristis) can be a serious insect pest for organic summer squash growers. The purpose of this research was to evaluate two methods to control A. tristis populations. The first experiment involved planting cover crops adjacent to summer squash in an effort to attract natural enemies to keep A. tristis populations in check. Natural enemies were attracted to the plots, but did not significantly reduce A. tristis populations. This may have been due to other food sources in the plots, such as pollen, nectar, and aphids. Also, summer squash yields were negatively affected by the cover crop treatments. The second experiment involved evaluating the efficacy of organic insecticides on A. tristis adults and nymphs. Results of this study showed pyrethrin-based sprays are best for controlling A. tristis. INDEX WORDS: Summer squash, Diversified planting, Natural enemies, Pesticides, Organic agriculture, Sustainable agriculture, Biological control EFFECTS OF COVER CROPS AND ORGANIC INSECTICIDES ON SQUASH BUG (ANASA TRISTIS) POPULATIONS by LINDSAY NICHOLE DAVIES B.S., Indiana University, 2011 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2016 © 2016 Lindsay Nichole Davies All Rights Reserved EFFECTS OF COVER CROPS AND ORGANIC INSECTICIDES ON SQUASH BUG (ANASA TRISTIS) POPULATIONS by LINDSAY NICHOLE DAVIES Major Professor: David Berle Committee: Paul Guillebeau Elizabeth Little Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2016 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my friends, family, and fiancé. -

E0020 Common Beneficial Arthropods Found in Field Crops

Common Beneficial Arthropods Found in Field Crops There are hundreds of species of insects and spi- mon in fields that have not been sprayed for ders that attack arthropod pests found in cotton, pests. When scouting, be aware that assassin bugs corn, soybeans, and other field crops. This publi- can deliver a painful bite. cation presents a few common and representative examples. With few exceptions, these beneficial Description and Biology arthropods are native and common in the south- The most common species of assassin bugs ern United States. The cumulative value of insect found in row crops (e.g., Zelus species) are one- predators and parasitoids should not be underes- half to three-fourths of an inch long and have an timated, and this publication does not address elongate head that is often cocked slightly important diseases that also attack insect and upward. A long beak originates from the front of mite pests. Without biological control, many pest the head and curves under the body. Most range populations would routinely reach epidemic lev- in color from light brownish-green to dark els in field crops. Insecticide applications typical- brown. Periodically, the adult female lays cylin- ly reduce populations of beneficial insects, often drical brown eggs in clusters. Nymphs are wing- resulting in secondary pest outbreaks. For this less and smaller than adults but otherwise simi- reason, you should use insecticides only when lar in appearance. Assassin bugs can easily be pest populations cannot be controlled with natu- confused with damsel bugs, but damsel bugs are ral and biological control agents. -

The Importance of Environmentally-Acquired Bacterial Symbionts for the Squash Bug (Anasa Tristis), a Significant Agricultural Pest

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.14.452367; this version posted July 14, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. The importance of environmentally-acquired bacterial symbionts for the squash bug (Anasa tristis), a significant agricultural pest Tarik S. Acevedo1, Gregory P. Fricker1, Justine R. Garcia1,2, Tiffanie Alcaide1, Aileen Berasategui1, Kayla S. Stoy, Nicole M. Gerardo1* 1Department of Biology, Emory University, 1510 Clifton Road, Atlanta, GA, 30322, USA 2Department of Biology, New Mexico Highlands University, 1005 Diamond Ave, Las Vegas, NM, 87701, USA *Correspondence: Nicole Gerardo [email protected] Keywords: squash bugs, Cucurbit Yellow Vine Disease, Coreidae, symbiosis, Caballeronia bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.14.452367; this version posted July 14, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 InternationalCaballeronia license. -Squash Bug Symbiosis ABSTRACT Most insects maintain associations with microbes that shape their ecology and evolution. Such symbioses have important applied implications when the associated insects are pests or vectors of disease. The squash bug, Anasa tristis (Coreoidea: Coreidae), is a significant pest of human agriculture in its own right and also causes damage to crops due to its capacity to transmit a bacterial plant pathogen. -

Egg Viability and Larval Penetration in Trichopoda Pennipes Pilipes Mohammad Shahjahan2 and John W. Beardsley, Jr.3 Trichopoda P

Vol. XXII, No. 1, August, 1975 '33 Egg Viability and Larval Penetration in Trichopoda pennipes pilipes Fabricius (Diptera: Tachinidae)1 Mohammad Shahjahan2 and John W. Beardsley, Jr.3 Trichopoda pennipes pilipes Fabricius was introduced into Hawaii from Trinidad in 1962 to combat the southern green stink bug, Nezara viridula (Fabricius) (Davis and Krauss, 1963; Davis, 1964). In Hawaii, T. p. pilipes has been reared from the scutellerid Coleotichus blackburni White and the pentatomids Thyanta accera (McAtee) and Plautia stali Scott, in addition to N. viridula. During 1965 we began a study on the biology of T. p. pilipes in rela tion to its principal host in Hawaii, N. viridula. Laboratory experiments and observations were conducted to evaluate the effects of superparasiti- zation of N. viridula by the tachinid on both the host and parasite pop ulations. The results of some of this work were reported previously (Shahjahan, 1968). The present paper summarizes data which were ob tained on parasite egg viability and larval penetration of host integument. The methods used in rearing and handling both N. viridula and T. p. pilipes were described in the earlier paper (Shahjahan, 1968). Supernumerary Oviposition and Egg Viability Adults of the southern green stink bug often are heavily superpara- sitized by T. p. pilipes, both in the field and under laboratory conditions. As many as 237 T. p. pilipes eggs were counted on a single field-collected stink bug, and a high of 275 eggs were deposited on one bug in the lab oratory (Shahjahan, 1968). Eggs are placed predominantly on the venter of the thorax, but may be deposited on almost any part of the host, in cluding the appendages, wings, eyes, etc. -

Two Coreidae (Hemiptera), Chelinidea Vittiger and Anasa Armigera, New for Arkansas, U.S.A. Stephen W

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 62 Article 23 2008 Two Coreidae (Hemiptera), Chelinidea vittiger and Anasa armigera, New for Arkansas, U.S.A. Stephen W. Chordas III The Ohio State University, [email protected] Peter W. Kovarik Columbus State Community College Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Chordas, Stephen W. III and Kovarik, Peter W. (2008) "Two Coreidae (Hemiptera), Chelinidea vittiger and Anasa armigera, New for Arkansas, U.S.A.," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 62 , Article 23. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol62/iss1/23 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This General Note is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 62 [2008], Art. 23 Two Coreidae (Hemiptera), Chelinidea vittiger and Anasa armigera, New for Arkansas, U.S.A. S. Chordas III1 and P. Kovarik2 1Center for Life Sciences Education, The Ohio State University, 260 Jennings Hall, 1735 Neil Avenue, Columbus, Ohio 43210 2 Columbus State Community College 239 Crestview Road, Columbus, Ohio 43202 1Correspondence: [email protected] Most leaf-footed bugs (Hemiptera: Coreidae) Herring (1980) and Froeschner (1988) in not occurring north of Mexico are essentially generalist recognizing subspecies of Chelinidea vittiger (which phytophagous insects feeding on tender shoots or were almost solely based on color variations). -

Squash Bugs of South Dakota Burruss Mcdaniel South Dakota State University

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletins SDSU Agricultural Experiment Station 1989 Squash Bugs of South Dakota Burruss McDaniel South Dakota State University Follow this and additional works at: http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/agexperimentsta_tb Part of the Entomology Commons, and the Plant Sciences Commons Recommended Citation McDaniel, Burruss, "Squash Bugs of South Dakota" (1989). Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletins. 12. http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/agexperimentsta_tb/12 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the SDSU Agricultural Experiment Station at Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletins by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. T B 92 quash Agricultural Experiment Station South Dakota State University U.S. Department of Agriculture T B 92 of South Dakota Burruss McDaniel Professor, Plant Science Department South Dakota State University COREi DAE (HEMIPTERA: HETEROPTERA) Agriopocorinae (this latter extrazimital) . Baranowski and Slater ( 1986), in their Coreidae of Florida, listed The family Coreidae is best known because of the 120 species dispersed among 18 genera, 9 tribes and 3 destructive habit of the squash bug, Anasa tristis, on subfamilies. squash, pumpkin, cucumber, and other members of the cucurbit family in the United States. The family, The material examined in this work is deposited in represented by various species, is found throughout the the SDSU H.C.