Andrea Dworkin, Heartbreak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Critical Impact of Transgressive Theatrical Practices Christopher J

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 (Im)possibilities of Theatre and Transgression: the critical impact of transgressive theatrical practices Christopher J. Krejci Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Krejci, Christopher J., "(Im)possibilities of Theatre and Transgression: the critical impact of transgressive theatrical practices" (2011). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3510. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3510 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. (IM)POSSIBILITIES OF THEATRE AND TRANSGRESSION: THE CRITICAL IMPACT OF TRANSGRESSIVE THEATRICAL PRACTICES A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Theatre by Christopher J. Krejci B.A., St. Edward’s University, 1999 M.L.A, St. Edward’s University, 2004 August 2011 For my family (blood and otherwise), for fueling my imagination with stories and songs (especially on those nights I couldn’t sleep). ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor, John Fletcher, for his expert guidance. I would also like to thank the members of my committee, Ruth Bowman, Femi Euba, and Les Wade, for their insight and support. -

Psychology: an International 11

WOMEN'S STUDIES LIBRARIAN The University ofWisconsin System EMINIST ERIODICALS A CURRENT LISTING OF CONTENTS VOLUME 13, NUMBER 3 FALL 1993 Published by Phyllis Holman Weisbard Women's Studies Librarian University of Wisconsin System 430 Memorial Library / 728 State Street Madison, Wisconsin 53706 (608) 263-5754 EMINIST ERIODICALS A CURRENT LISTING OF CONTENTS Volume 13, Number 3 Fall 1993 Periodical literature is the cutting edge of women's scholarship, feminist theory, and much ofwomen'sculture. Feminist Periodicals: A Current Listing of Contents is published by the Office of the University of Wisconsin System Women's Studies Librarian on a quarterly basis with the intent of increasing pUblic awareness of feminist periodicals. It is our hope that Feminist Periodicals will serve several purposes: to keep the reader abreast of current topics in feminist literature; to increase readers' familiarity with a wide spectrum of feminist periodicals; and to provide the requisite bibliographic information should a reader wish to subscribe to ajournal or to obtain a particular article at her library or through interlibrary lOan. (Users will need to be aware of the limitations of the new copyright law with regard to photocopying of copyrighted materials.) Tabie of contents pages from current issues of majorfeminist journals are reproduced in each issue ofFeminist Periodicals, preceded by a comprehensive annotated listing of all journals we have selected. As pUblication schedules vary enormously, not every periodical will have table of contents pages reproduced in each issue of IT. The annotated listing provides the following information on each journal: 1. Year of first publication. 2. Frequency of pUblication. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Prostitution, Trafficking, and Cultural Amnesia: What We Must Not Know in Order to Keep the Business of Sexual Exploitation Running Smoothly

Prostitution, Trafficking, and Cultural Amnesia: What We Must Not Know in Order To Keep the Business of Sexual Exploitation Running Smoothly Melissa Farleyt INTRODUCTION "Wise governments," an editor in the Economist opined, "will accept that. paid sex is ineradicable, and concentrate on keeping the business clean, safe and inconspicuous."' That third adjective, "inconspicuous," and its relation to keeping prostitution "ineradicable," is the focus of this Article. Why should the sex business be invisible? What is it about the sex industry that makes most people want to look away, to pretend that it is not really as bad as we know it is? What motivates politicians to do what they can to hide it while at the same time ensuring that it runs smoothly? What is the connection between not seeing prostitution and keeping it in existence? There is an economic motive to hiding the violence in prostitution and trafficking. Although other types of gender-based violence such as incest, rape, and wife beating are similarly hidden and their prevalence denied, they are not sources of mass revenue. Prostitution is sexual violence that results in massive tMelissa Farley is a research and clinical psychologist at Prostitution Research & Education, a San Francisco non-profit organization, She is availabe at [email protected]. She edited Prostitution, Trafficking, and Traumatic Stress in 2003, which contains contributions from important voices in the field, and she has authored or contributed to twenty-five peer-reviewed articles. Farley is currently engaged in a series of cross-cultural studies on men who buy women in prostitution, and she is also helping to produce an art exhibition that will help shift the ways that people see prostitution, pornography, and sex trafficking. -

January/February 2017 | Volume 3, Issue No

QUEENS LIBRARY MAGAZINE January/February 2017 | Volume 3, Issue No. 1 Food industry entrepreneurs will love Jamaica FEASTS p.4 Queens Library can help with your New Year’s resolutions p.6 Roxanne Shanté Here’s what you missed at Festival an Koulè p.9 Headlines Broken What’s on this African- American History Month p.11 Heart Week p.15 QueensLibrary.org 1 QUEENS LIBRARY MAGAZINE A Message from the President and CEO Dear Friends, At Queens Library, we are continually working to understand how best to serve the dynamic needs of its diverse communities. To ensure that the Library can be as meaningful and effective as possible in these increasingly complex times, we have embarked on a strategic planning process that will guide the Library for the next five years. The success of this process depends on your engagement. We are seeking the input of a broad range of stakeholders and ultimately determining how the Library defines its mission and vision, sets its priorities, uses its resources, and secures its position as one of the most vital institutions in the City of New York. As part of this ambitious and highly inclusive planning process, we are conducting a series of discussions with everyone who uses, could use, serves, oversees, funds, and appreciates Queens Library about its strengths and weaknesses as well as the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead. One of the most critical conversations we want to have is with you. To get the Sincerely, dialogue started, please visit our website, www.queenslibrary.org, to take a survey about your experiences with the Library and your thoughts about its future. -

Events and Happenings March 2016 Spring Begins March 20

Events and Happenings March 2016 Spring Begins March 20 Jeff Manes Book Signing Lowell Public Library Author and Syndicated Columnist 1505 East Commercial Lowell, IN 46356 Saturday, March 12 — 1-4 PM phone 696-7704 fax 696-5280 Jeff Manes, writer of the syndicated newspaper www.lowellpl.lib.in.us column Salt, returns with All Worth Their Salt: The People of NWI, Volume 2. Hours Since 2005, Jeff has written over 1000 articles about Mon.-Thurs. 9 AM-8 PM people from all over the Calumet region. The stories Fri.- Sat. 9 AM- 5 PM are interesting, heartwarming, funny and heart- breaking, and tell of the lives of many people that Jeff has interviewed over the years. Schneider Branch 24002 Parrish Ave. After the reading, Jeff will sign books. (Books can Schneider, IN 46376 be purchased for $25.00 at the program). Please 552-1000 pre-register at the circulation desk. School Year Hours Mon.-Thurs. 3:30--7 PM Happy Hoosier Bicentennial Presentation Fri. CLOSED featuring Terry Lynch as President Benjamin Harrison Sat. 10 AM–12 NOON Wednesday, March 23 — 6 PM Shelby Branch Celebrate Indiana’s 200th Birthday! 23323 Shelby Rd Shelby, IN 46377 The festivities celebrating the 19th state’s 552-0809 admission to the Union come to a fever pitch when the 23rd President of the United States, Benjamin Harrison of Indianapolis, brings into School Year Hours focus the history, industry, natural resources, politics and entertainment that enabled the great Mon. 9 AM-12 & 1-6 PM state of Indiana to influence the nation. Tues–Thurs. -

The Daily Egyptian, September 13, 1984

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC September 1984 Daily Egyptian 1984 9-13-1984 The aiD ly Egyptian, September 13, 1984 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_September1984 Volume 70, Issue 19 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, September 13, 1984." (Sep 1984). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1984 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in September 1984 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bid muddles convention center plans My Bob Tila Simon. said Wednesday that FmHA 5 rcc-c.,s . of 60 da~ s. Monty said. The cIty IS a lso S l a rf\\' rit~r africa Is in Champaign have indica ted Federa l tax legisla tion passed in wailing for a tt.."lsibility report on the that they would approve continued August also affects the plans submitted center to be released later this month. The Carbondale convention center is support for the convention cent er. He by lhe National GroupofCompanies. in a familia r place again - li mbo, Monty said the city will not be actively said an extension of support from The Nationa.l Group of Companies ha s involved in working out an agreement City Council members expressed FmHA officials in Washington is still offered to buIld the conventIOn center in terest in an offer to build the con· between Stan Hoye and the Nalional pending. without financial guarantees irom the League of Companies. He said. -

The Breakup Project: Using Evolutionary Theory to Predict and Interpret Responses to Romantic Relationship Dissolution

Binghamton University The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) Graduate Dissertations and Theses Dissertations, Theses and Capstones 2015 The Breakup Project: Using Evolutionary Theory to Predict and Interpret Responses to Romantic Relationship Dissolution Craig E. Morris Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/dissertation_and_theses Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Morris, Craig E., "The Breakup Project: Using Evolutionary Theory to Predict and Interpret Responses to Romantic Relationship Dissolution" (2015). Graduate Dissertations and Theses. 2. https://orb.binghamton.edu/dissertation_and_theses/2 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations, Theses and Capstones at The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Breakup Project: Using Evolutionary Theory to Predict and Interpret Responses to Romantic Relationship Dissolution BY CRAIG ERIC MORRIS BA, Pennsylvania State University, 1992 BA, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, 2007 MA, Binghamton University, 2010 DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate School of Binghamton University State University of New York 2015 UMI Number: 3713604 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマットジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL Al Gorgoni/Trade Martin

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマットジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL Al Gorgoni/Trade Martin/Chip Taylorガッタ・ゲット・バック・トゥ・シスコ&ゴーゴニ・マーティン&テイラーBSMF7512 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,400 https://tower.jp/item/3694855 Alan Jackson プレシャス・メモリーズ VOL.2 WRSI157 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,100 https://tower.jp/item/3227864 Ana Popovic Like It on Top AXR6 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,390 https://tower.jp/item/4773972 Anders Osborne ブラック・アイ・ギャラクシー PCD93549 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,300 https://tower.jp/item/3082492 Appalachian Road Show Barry Abernathy & Darrell Webb Present NEDY7602 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,390 https://tower.jp/item/4804207 Ashley Monroe Sparrow(US/LP) 1565008 Analog COUNTRY/BLUES 2,890 https://tower.jp/item/4704216 Ayiesha Woods INTRODUCING HMSB2025 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 1,980 https://tower.jp/item/2122666 B.B. Driftwood Southward Bound(HB) CD22112 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,590 https://tower.jp/item/4666771 B.B. King Live at San Quentin(LP) L79193 Analog COUNTRY/BLUES 2,990 https://tower.jp/item/3273204 B.B. King The Life Of Riley (Two Disc Version)(OST/INTL/2CD) 5340882 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 1,990 https://tower.jp/item/3161078 Barefoot 7 ウェインズ・ワールド SRCD1004 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,857 https://tower.jp/item/960381 Bert Jansch A Rare Conundrum(UK) EARTHCD028 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,090 https://tower.jp/item/4766726 Big Daddy Wilson ネックボーン・シチュー BSMF2546 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,400 https://tower.jp/item/4438023 Big Daddy Wilson ソングス・フロム・ザ・ロード [CD+DVD] BSMF2612 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,700 https://tower.jp/item/4731723 Big Jay McNeely/BLOODEST SAXOPHONEライヴ・イン・ジャパン FAMC214 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,300 https://tower.jp/item/4121348 Big Joe Turner ザ・リアル・ボス・オブ・ザ・ブルース(+2) -

Collaborative Explorations

The Journal of Mathematics and Science: COLLABORATIVE EXPLORATIONS Volume 15, Spring 2015 PART I: SPECIAL ISSUE The Virginia Initiative for Science Teaching and Achievement (VISTA) PART II: REGULAR JOURNAL FEATURES Virginia Mathematics and S{: ience Coalition The Journal of Mathematics and Science: COLLABORATIVE EXPLORATIONS Editor A Ellington Virginia Commonwealth University Associate Editors J Boyd S Khanna St. Christopher's School Virginia Commonwealth University J Cothron J Lewis Virginia Mathematics and Science University of Nebraska-Lio.coin Coalition P McNeil N Davila Norfolk State University University of Puerto Rico R Millman T Dick Georgia Institute of Technology Oregon State University L Pitt D Erchick University of Virginia Ohio State University - Newark D Royster R Farley University of Kentucky Virginia Commonwealth University P N Raychowdhury L Fathe Virginia Commonwealth University Owens Community College S Solomon S Garfunkel Drexel University COMAP D Sterling J Garofalo George Mason University University of Virginia P Sztajn T Goodman North Carolina State University University of Central Missouri B Williams W Haver Williamsburg/James City Schools Virginia Commonwealth University S Wyckoff W Hawkins Arizona State University Mathematical Association ofAmerica R Howard University of Tvisa The Journal of Mathematics and Science: COLLABORATIVE EXPLORATIONS Volume 15, Spring 2015 PART I: SPECIAL ISSUE The Virginia Initiative for Science Teaching and Achievement (VISTA) PART II: REGULAR JOURNAL FEATURES Virginia Mathematics and Science Coalition The Journal of Mathematics and Science: COLLABORATIVE EXPLORATIONS Volume 15, Spring 2015 PART I: SPECIAL ISSUE The Virginia Initiative for Science Teaching and Achievement (VISTA) Virginia Mathematics and Science Coalition The Journal of Mathematics and Science: COLLABORATIVE EXPLORATIONS SPECIAL ISSUE The Virginia Initiative for Science Teaching and Achievement (VISTA) Coordinating Editor for this Special Issue Donna Sterling George Mason University Funding for this Special Issue was provided by The U.S. -

May Hiraga Said Dukakis Promised a Cure for Address the AIDS Issue," He Said

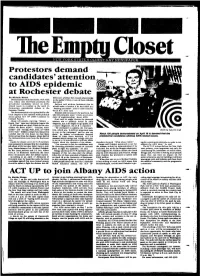

MH ———' •"*- —iw-TiBwaB-i vmmmm unat-Minw Protestors demand candidates' attention to AIDS epidemic at Rochester debate By Michele Moore fered over whether they would acknowledge Demonstrators from Rochester, New York to thc public if they or one of their children City, Ithaca and Cleveland protested the had AIDS presidential candidates' silence on AIDS- Jackson said without hesitation that he related issues in a picket at thc April 16 would make it known if he had AIDS as a Democratic presidential debate at the "healing procedure" and to calm hysteria, Eastman Theatre. thc D & C story said. The demonstration was sponsored by thc Dukakis did not answer the question, but local chapter of the national AIDS political said thc president must "create an environ action group ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to ment of understanding" aliout AIDS. Unleash Power). Gore said he might choose for personal Atiout 120 people, carrying "Silence = reasons not to publicly reveal an AIDS Death. Vote'* signs and chanting slogans like diagnosis, Just as he might not go public with '32,000 people arc dead! What do thc can a cancer diagnosis, the D&C reported. didates say about AIDS?", '^Educate, don't "He attempted to address the real ques isolate!" and **Gcorgc Mike, Jesse, A1--AIDS tion, which was, 'Is AIDS an important issue photo by Autumn Craft won't wait!" walked, jumped and danced in to you in thc campaign?' and he was cut a picket line for two hours on East Main short" by debate co-moderator Bernard About 120 people demonstrated on April 16 to demand that ttie Street across from thc theater. -

URL Al King/Arthur K. Adams

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL Al King/Arthur K. Adams Together : The Complete Kent And Modern Recordings(UK) CDCHD1292 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,090 https://tower.jp/item/2814834 Appalachian Road Show Barry Abernathy & Darrell Webb Present NEDY7602 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,390 https://tower.jp/item/4804207 Arlo Guthrie The Best Of Arlo Guthrie <Translucent Green Vinyl>(EU/LP) 349785208 Analog COUNTRY/BLUES 2,990 https://tower.jp/item/4922304 B.B. King More B.B. King <限定盤>(+4/LP) PAN9152313 Analog COUNTRY/BLUES 3,290 https://tower.jp/item/4899044 B.B. King The Complete Singles As & Bs: 1949-62 (5CD) ACFCD7504 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,990 https://tower.jp/item/3944041 Big Daddy Wilson/Vanessa Collier/ブルース キャラヴァン 2017 [CD+DVD] BSMF2606 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,700 https://tower.jp/item/4706545 Big Joe Turner Live 1983(UK) FLOATM6212 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,090 https://tower.jp/item/3359254 Big Pete ライブ アット ブルースナウ! BSMF2652 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,400 https://tower.jp/item/4866260 Big Pete チョイス カッツ BSMF2255 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,381 https://tower.jp/item/3007762 Big Sam's Funky Nation テイク ミー バック(+2) PVCP8246 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,330 https://tower.jp/item/2167664 Billy Flynn Lonesome Highway S73021 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,390 https://tower.jp/item/4457683 Billy Price/Otis Clay This Time for Real(DIGI) BNOG462 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,390 https://tower.jp/item/3881602 Blind Blake Early Morning Blues: Essential Recordings 1926-1932(DIGI/RM) SJ806172 CD COUNTRY/BLUES 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4871996 Blind Willie Johnson The Complete Recordings Of Blind Willie Johnson 4830245 CD COUNTRY/BLUES