Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) Integrated Governance Activity (IGA) Is a Five-Year Program, Ending on January 8, 2022, and Implemented by DAI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Year in Review 2008

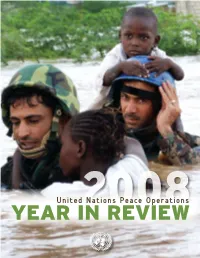

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

DR-CONGO December 2013

COUNTRY REPORT: DR-CONGO December 2013 Introduction: other provinces are also grappling with consistently high levels of violence. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DR-Congo) is the sec- ond most violent country in the ACLED dataset when Likewise, in terms of conflict actors, recent international measured by the number of conflict events; and the third commentary has focussed very heavily on the M23 rebel most fatal over the course of the dataset’s coverage (1997 group and their interactions with Congolese military - September 2013). forces and UN peacekeepers. However, while ACLED data illustrates that M23 has constituted the most violent non- Since 2011, violence levels have increased significantly in state actor in the country since its emergence in April this beleaguered country, primarily due to a sharp rise in 2012, other groups including Mayi Mayi militias, FDLR conflict in the Kivu regions (see Figure 1). Conflict levels rebels and unidentified armed groups also represent sig- during 2013 to date have reduced, following an unprece- nificant threats to security and stability. dented peak of activity in late 2012 but this year’s event levels remain significantly above average for the DR- In order to explore key dynamics of violence across time Congo. and space in the DR-Congo, this report examines in turn M23 in North and South Kivu, the Lord’s Resistance Army Across the coverage period, this violence has displayed a (LRA) in northern DR-Congo and the evolving dynamics of very distinct spatial pattern; over half of all conflict events Mayi Mayi violence across the country. The report then occurred in the eastern Kivu provinces, while a further examines MONUSCO’s efforts to maintain a fragile peace quarter took place in Orientale and less than 10% in Ka- in the country, and highlights the dynamics of the on- tanga (see Figure 2). -

Dismissed! Victims of 2015-2018 Brutal Crackdowns in the Democratic Republic of Congo Denied Justice

DISMISSED! VICTIMS OF 2015-2018 BRUTAL CRACKDOWNS IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DENIED JUSTICE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: “Dismissed!”. A drawing by Congolese artist © Justin Kasereka (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 62/2185/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 2. METHODOLOGY 9 3. BACKGROUND: POLITICAL CRISIS 10 3.1 ATTEMPTS TO AMEND THE CONSTITUTION 10 3.2 THE « GLISSEMENT »: THE LONG-DRAWN-OUT ELECTORAL PROCESS 11 3.3 ELECTIONS AT LAST 14 3.3.1 TIMELINE 15 4. VOICES OF DISSENT MUZZLED 19 4.1 ARBITRARY ARRESTS, DETENTIONS AND SYSTEMATIC BANS ON ASSEMBLIES 19 4.1.1 HARASSMENT AND ARBITRARY ARRESTS OF PRO-DEMOCRACY ACTIVISTS AND OPPONENTS 20 4.1.2 SYSTEMATIC AND UNLAWFUL BANS ON ASSEMBLY 21 4.2 RESTRICTIONS OF THE RIGHT TO SEEK AND RECEIVE INFORMATION 23 5. -

Mapping Conflict Motives: M23

Mapping Conflict Motives: M23 1 Front Cover image: M23 combatants marching into Goma wearing RDF uniforms Antwerp, November 2012 2 Table of Contents Introduction 4 1. Background 5 2. The rebels with grievances hypothesis: unconvincing 9 3. The ethnic agenda: division within ranks 11 4. Control over minerals: Not a priority 14 5. Power motives: geopolitics and Rwandan involvement 16 Conclusion 18 3 Introduction Since 2004, IPIS has published various reports on the conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Between 2007 and 2010 IPIS focussed predominantly on the motives of the most significant remaining armed groups in the DRC in the aftermath of the Congo wars of 1996 and 1998.1 Since 2010 many of these groups have demobilised and several have integrated into the Congolese army (FARDC) and the security situation in the DRC has been slowly stabilising. However, following the November 2011 elections, a chain of events led to the creation of a ‘new’ armed group that called itself “M23”. At first, after being cornered by the FARDC near the Rwandan border, it seemed that the movement would be short-lived. However, over the following two months M23 made a remarkable recovery, took Rutshuru and Goma, and started to show national ambitions. In light of these developments and the renewed risk of large-scale armed conflict in the DRC, the European Network for Central Africa (EURAC) assessed that an accurate understanding of M23’s motives among stakeholders will be crucial for dealing with the current escalation. IPIS volunteered to provide such analysis as a brief update to its ‘mapping conflict motives’ report series. -

NO19-Digital Media in Central Africa.Indd

REFERENCE SERIES NO. 19 MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: NEWS AND NEW MEDIA IN CENTRAL AFRICA. CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES By Marie-Soleil Frère December 2012 News and New Media in Central Africa. Challenges and Opportunities WRITTEN BY Marie-Soleil Frère1 Th e Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is the largest country in sub-Saharan Africa. Rwanda and Burundi are among the continent’s smallest states. More than just neighbors, these three countries are locked together by overlapping histories and by extreme political and economic challenges. Th ey all score very low on the United Nations’ human development index, with DRC and Burundi among the half-dozen poorest and most corrupt countries in the world. Th ey are all recovering uncertainly from confl icts that involved violence on an immense scale, devastating communities and destroying infrastructure. Th eir populations are overwhelmingly rural and young. In terms of media, radio is by far the most popular source of news. Levels of state capture are high, and media quality is generally poor. Professional journalists face daunting obstacles. Th e threadbare markets can hardly sustain independent outlets. Amid continuing communal and political tensions, the legacy of “hate media” is insidious, and upholding journalism ethics is not easy when salaries are low. Ownership is non-transparent. Telecoms overheads are exorbitantly high. In these conditions, new and digital media—which fl ourish on consumers’ disposable income, strategic investment, and vibrant markets—have made a very slow start. Crucially, connectivity remains low. But change is afoot, led by the growth of mobile internet access. 1. Marie-Soleil Frère is Senior Research Associate at the National Fund for Scientifi c Research (Belgium) and Director of the Research Center in Information and Communication (ReSIC) at the University of Brussels. -

Radio Okapi's Contribution to the Peace Process in The

PUBLIC INFORMATION AND THE MEDIA: RADIO OKAPI’S CONTRIBUTION TO THE PEACE PROCESS IN THE DRC Jerome Ngongo Taunya1 Introduction There are many reasons to be optimistic about the progress made thus far on the way to peace in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The DRC now has one government, one parliament, one army commander. This much has already been achieved. However, we still have a long way to go before making this process a success. The northeastern Ituri district and the two Kivu provinces are still unstable; the question of the integration of the armies and police remains and is yet to be addressed; several delicate issues still face the new government; and all the transitional institutions will need some time to be consolidated. The electoral challenge, which is the final objective of the process, is still to be met, and this will require a great deal of commitment from those working in public infor- mation. Therefore, media support to the peace process must continue apace. The role of the media and the public information division of MONUC is certainly crucial. The success of the reconciliation process will depend heavily on the capacity of the Congolese media to capture the attention of the population, to provide them with fluid, useful, and balanced information. The media are needed to harness wide participation in the process by the Congolese people. The people of Congo need to be given the tools to allow them to master their destiny. They need to be accurately informed and educated, so they can better understand what is done for them and what they have to do for themselves. -

The Evolution of an Armed Movement in Eastern Congo Rift Valley Institute | Usalama Project

RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE | USALAMA PROJECT UNDERSTANDING CONGOLESE ARMED GROUPS FROM CNDP TO M23 THE EVOLUTION OF AN ARMED MOVEMENT IN EASTERN CONGO rift valley institute | usalama project From CNDP to M23 The evolution of an armed movement in eastern Congo jason stearns Published in 2012 by the Rift Valley Institute 1 St Luke’s Mews, London W11 1Df, United Kingdom. PO Box 30710 GPO, 0100 Nairobi, Kenya. tHe usalama project The Rift Valley Institute’s Usalama Project documents armed groups in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The project is supported by Humanity United and Open Square and undertaken in collaboration with the Catholic University of Bukavu. tHe rift VALLEY institute (RVI) The Rift Valley Institute (www.riftvalley.net) works in Eastern and Central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. tHe AUTHor Jason Stearns, author of Dancing in the Glory of Monsters: The Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa, was formerly the Coordinator of the UN Group of Experts on the DRC. He is Director of the RVI Usalama Project. RVI executive Director: John Ryle RVI programme Director: Christopher Kidner RVI usalama project Director: Jason Stearns RVI usalama Deputy project Director: Willy Mikenye RVI great lakes project officer: Michel Thill RVI report eDitor: Fergus Nicoll report Design: Lindsay Nash maps: Jillian Luff printing: Intype Libra Ltd., 3 /4 Elm Grove Industrial Estate, London sW19 4He isBn 978-1-907431-05-0 cover: M23 soldiers on patrol near Mabenga, North Kivu (2012). Photograph by Phil Moore. rigHts: Copyright © The Rift Valley Institute 2012 Cover image © Phil Moore 2012 Text and maps published under Creative Commons license Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by/nc-nd/3.0. -

FY 2003 USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE to the DRC Agency Implementing Sector Regions Amount Partner FY 2003 USAID

FY 2003 USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO THE DRC Agency Implementing Sector Regions Amount Partner FY 2003 USAID ............................................................................................................................................... $35,042,261 USAID/ofda1 ..................................................................................................................................... $10,442,261 Action Against Food security Northern Katanga $700,000 Hunger/USA Province AirServ Air transport Country-wide $2,465,567 International German Agro Food security Ituri District $862,872 Action (GAA) IRC Health, and water and sanitation South Kivu Province $600,000 IRC Water and sanitation Mwenga, South Kivu $1,500,000 Province IRC Health Kalemie, Northern $500,000 Katanga Province MERLIN Health Ituri District $1,000,000 Premiere Urgence Food security Ituri District $600,000 SCF/UK Volcano monitoring and mitigation Goma, North Kivu $341,176 Province SCF/UK Child reunification Ituri District $39,386 Solidarites Food security Ituri District $71,000 UN FAO Food security Country-wide $700,000 UN OCHA Seismic monitoring and mitigation Country-wide $180,000 WFP Air transport of emergency food Northern Katanga $500,000 Province Administrative Kinshasa and $382,260 Costs Washington, D.C. USAID/FFP........................................................................................................................................ $20,000,000 WFP 21,770 MT in P.L. 480 Title II Emergency Country-wide $20,000,000 Food Assistance -

La Cruenta Transición Del Gigante Congoleño Hacia La Democracia Visitar La WEB Recibir BOLETÍN ELECTRÓNICO

Documento Opinión 45/2017 27 de abril de 2017 Andrés González Cervera* La cruenta transición del gigante congoleño hacia la democracia Visitar la WEB Recibir BOLETÍN ELECTRÓNICO La cruenta transición del gigante congoleño hacia la democracia Resumen: El 19 de diciembre de 2016 expiró el segundo y último mandato constitucional del presidente de la República Democrática del Congo (RDC), Joseph Kabila, sin que este hubiera convocado elecciones. Desde entonces, el país africano sufre una crisis institucional agravada por el surgimiento de nuevos conflictos, especialmente en el Gran Kasai con la revuelta de la milicia Kamwina Nsapu. El 31 de diciembre de 2016 se firmó el Acuerdo de San Silvestre, gracias a la intermediación de la Iglesia, entre la mayoría presidencial y las fuerzas de la oposición para asegurar la continuidad del Estado y de las instituciones de la República y para organizar elecciones en diciembre de 2017. Sin embargo, el Gobierno de Kabila ha obstaculizado constantemente el cumplimiento del Acuerdo y la celebración de las elecciones este año no está asegurada. Abstract: In December, 19, 2016, Joseph Kabila’s —president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) — second and last mandate expired, not holding elections. Since then, the African country suffers an institutional crisis worsened by the emergence of new conflicts, especially in Great Kasai with Kamwina Nsapu militia’s revolt. In December, 31, 2016, Saint Sylvester’s Agreement was signed by presidential majority and the opposition forces, thanks to the Church’s intermediation, in order to assure the continuity of the State and the Republic Institutions, and most importantly to hold elections in December, 2017. -

012/BARBARA-WK-DRC/2021 Goma, March 19Th, 2021

Barbara asbl Réf N° : 012/BARBARA-WK-DRC/2021 Goma , March 19 th , 2021 Sent copies for Information to: His Excellency the President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo Excellency the Prime Minister of DR Congo; Mr Minister of Public Health in DR Congo Mr Representative of the European Union in DR Congo Mr Representative of the World Health Organization in DR Congo Mr Head of the Joint United Nations Human Rights Office (UNJHRO) in DR Congo The Representative of the International Committee of the Red Cross in DR Congo Mr. General Managing Director of the REGIDESO in DRCongo Mr. Representative of MERCY CORPS in DRCongo (All) in Kinshasa ; Mr. Provincial Minister of Town Planning and Housing Ms President of Waterkeeper Alliance in New York/USA Ms Representative of Human Rights Watch in RD Congo Honorable President of the Provincial Assembly of North Kivu (To) Honorable Provincial and National Deputies Elected of the City of Goma The Provincial Minister of Public Health and Environment of North Kivu The Provincial Director of REGIDESO The Executive Secretary of Provincial Government of NK; The President of the Public Prosecutor's Office near the Tribunal de Grande Instance in Goma The Mayor of Goma The Focal Point of ANYL4PSD in RDC Mr the Provincial President of the Civil Society of North Kivu The Head of UNICEF/ Sub Office of Goma, Mr the Head of Office MERCY CORPS Office of Goma Mr the Head of the ICRC office The Director of Radio Okapi/ Goma; Gentlemen, Directors of local / foreign Radio / TV; (All) in Goma (All )Partners BUREAU: Barbara Centre . -

Weekly Briefing 30Th October - 5Th November 2014

WEEKLY BRIEFING 30TH OCTOBER - 5TH NOVEMBER 2014 IPIS is an independent research institute which focuses on Sub-Saharan Africa. Our studies concern three core themes: arms trade, exploitation of natural resources and corporate social responsibility. This briefing provides a round-up of the week's news and analysis on security, natural resource and CSR issues arising in the Great Lakes region of Africa Content NEWS IN BRIEF News in brief In the Democratic Republic of Congo, events in Burkina Faso this week are said to have prompted Congolese authorities to clamp down on demonstrations against constitutional IPIS’ Latest Publications reform in Kinshasa with 200 arrests. Ongoing violence in North Kivu was in the spotlight this week as Joseph Kabila visited Beni, promising to put an end to the violence attributed to ADF militia and requesting an increased MONUSCO presence in the region. Further massacres this Conflict and security week – 14 dead in the village of Kampi ya Chui on Wednesday night and around 8 killed by DRC gunmen in Rwenzori on Saturday – has seen public anger prompt further protest about the Rwanda insecurity. On Monday, clashes erupted between the ADF and FARDC on the outskirts of Beni Burundi town, with unconfirmed reports of three deaths by the second day. On Wednesday an joint Uganda operation between MONUSDCO and the Congolese police saw the announcement of over 200 CAR arrests in connection with the killings – among them Congolese citizens. In Katanga the preceding week reportedly saw ten Bakata Katanga attacks within the space of a week in Moero sector, Pweto territory, whilst this week has seen thousands flee following attacks on Humanitarian news villages in Mitwaba territory. -

Public Information and Outreach in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Calendar of Activities – March 2009

Public Information and Outreach in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Calendar of activities – March 2009 General Objectives: • Publicise judicial activities before the Court, in particular the Lubanga trial • Ensure the broadcasting of video and audio programmes about the Court, in particular about the trial • Ensure the success of the Registrar’s mission to Kinshasa and Ituri Activity Date Place Summary Evaluation Tools Broadcast of 1, 7, 8, 9, Kinshasa Distribution of “The ICC at a glance” Audience hearing summaries 13, 14 videos for television broadcast; the ratings by RTNC and and 15 video summarises judicial Digital TV March developments in the Lubanga trial. Presentation of 2 March Cepas Centre, Show efforts made in outreach, goals Media 2008 report on Kinshasa attained and remaining challenges. coverage outreach activities The PIDS team also presented the and activities activities planned for 2009, in planned for this particular to focus attention on the year trial. Participants: 32 media outlets and partner NGOs, diplomatic missions. Issuance of press 4 March Kinshasa and Distribution of press release entitled Media release on the Bunia, Ituri “ICC issues a warrant of arrest for coverage issuance of an Omar Al Bashir, President of Sudan” arrest warrant for to journalists and partners to ensure Al Bashir that the information reaches the general public. Issuance of press 5 and 6 Kinshasa and Distribution of press release entitled Media release following March Bunia, Ituri “Bemba case: The judges ask the coverage the judges’ Prosecutor to submit an amended decision in the document containing the charges” to Bemba case journalists and partners to ensure that the information reaches the general public.