Psychological Contract Inside the Minds of the High Fliers Gwen Rogan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 59 – Summer 2005

ON COMMERCIAL AVIATION SAFETY SUMMER 2005 ISSUE 59 THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE ISSN 1355-1523 UNITED KINGDOM FLIGHT1 SAFETY COMMITTEE As Easy As Jeppesen’s EFB provides a flexible, scalable platform to deploy EFB applications and data that will grow 1,2,3 with you as your needs evolve. Class 1 Class 2 Class 3 Less paper; increased safety and efficiency; rapid ROI. Jeppesen's EFB makes it as easy as 1, 2, 3. Get more information at: 303.328.4208 (Western Hemisphere) +49 6102 5070 (Eastern Hemisphere) www.jeppesen.com/efb The Official Publication of THE UNITED KINGDOM FLIGHT SAFETY COMMITTEE ISSN: 1355-1523 SUMMER 2005 ON COMMERCIAL AVIATION SAFETY FOCUS is a quarterly subscription journal devoted to the promotion of best practises in contents aviation safety. It includes articles, either original or reprinted from other sources, related Editorial 2 to safety issues throughout all areas of air transport operations. Besides providing information on safety related matters, FOCUS aims to promote debate and improve Chairman’s Column 3 networking within the industry. It must be emphasised that FOCUS is not intended as a substitute for regulatory information or company Air Carrier Liability: EPA study reveals water 4 publications and procedures.. contamination in one aircraft in seven Editorial Office: Ed Paintin The Graham Suite BALPA Peer Intervention Seminar 5 Fairoaks Airport, Chobham, Woking, Surrey. GU24 8HX Tel: 01276-855193 Fax: 01276-855195 e-mail: [email protected] (Almost) Everything you Wanted to Know about RAS 6 Web Site: www.ukfsc.co.uk and RIS but were afraid to ask – A Pilot’s Guide Office Hours: 0900 - 1630 Monday - Friday Advertisement Sales Office: UKFSC What is a Flight Data Monitoring Programme? 8 The Graham Suite, by David Wright Fairoaks Airport, Chobham, Woking, Surrey GU24 8HX Tel: 01276-855193 Fax: 01276-855195 email: [email protected] There are Trainers at the Bottom of our Cowlings! 11 Web Site: www.ukfsc.co.uk by David C. -

Aer Arann Islands Aer Lingus

REG A/C TYPE ICAO OPERATOR NOTES LAST UPDATED: 03 OCT 21 AER ARANN ISLANDS RE / REA "AER ARANN" BRITTEN-NORMAN BN-2 ISLANDER EI-AYN BN-2A-8 Islander BN2P Galway Aviation Services EI-BCE BN-2A-26 Islander BN2P Galway Aviation Services EI-CUW BN-2B-26 Islander BN2P Galway Aviation Services AER LINGUS IRELAND = EI / EIN "SHAMROCK" UK = EG / EUK "GREEN FLIGHT" AIRBUS A32S EI-CVA A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-CVB A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-CVC A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-DEE A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-DEF A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-DEG A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-DEH A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-DEI A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus Special c/s EI-DEJ A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-DEK A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-DEL A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-DEM A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-DEN A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-DEO A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus Special c/s EI-DEP A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-DER A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-DES A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-DVE A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-DVG A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-DVH A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-DVI A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-DVJ A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-DVK A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-DVL A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-DVM A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus Special c/s EI-DVN A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-EDP A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-EDS A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-FNJ A320-216 A320 Aer Lingus EI-GAL A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-GAM A320-214 A320 Aer Lingus EI-CPE A321-211 A321 Aer Lingus WFU EI-CPG A321-211 A321 Aer Lingus WFU EI-CPH A321-211 A321 Aer Lingus WFU EI-LRA A321-253NX(LR) A21N Aer Lingus EI-LRB A321-253NX(LR) -

Más Información En Más Información En

IAA Website - Saturday, August 14, 2021 9:31 AM Más información en www.tmas.es Part 145 Aer Lingus Ltd. Approval No. IE.145.034 P.O. Box 180 Dublin Airport Co. Dublin Tel: 01 886 2222 Fax: 01 886 3832 Ratings: A1, C5, C6, C15, C18 Más información en www.tmas.es Aero Engines Ireland Ltd. Approval No. IE.145.030 Omega House Collinstown Cross Cloughran Co. Dublin Tel: 01 836 8684 Fax: 01 837 4470 Ratings: B1, C7, D1 Aero Inspection International Approval No. IE.145.051 Unit 2 Distribution Centre SFZ Shannon Airport Co. Clare Tel: 061 353 747 Fax: 061 353 737 Ratings : B1, B3 (Boroscope, Boroblend), C5 Altitude Engineering Limited Approval No. IE.145.0088 Digital Office Centre Balheary Road Swords Co. Dublin Tel: 01 541 3700 Email: [email protected] Web: www.altitudeengineering.ie Ratings: A1 Andona Aviation 145 Approval No. IE.145.079 Dublin Airport Forrest Great Swords Dublin Ratings: A3, C5 Apex Aviation Ltd. Approval No. IE.145.086 Unit 4 Annaholty Birdhill Co. Tipperary Ratings : B1, C7 Apex Aviation LMS Ltd. Approval No. IE.145.089 Unit 4 Annaholty Birdhill Co. Tipperary Workplace address: Office 39 Wings 4 & 5 Shannon Airport Co. Clare V14 EE06 Tel: 061 219 372 Email: [email protected] Web: www.apexaviation.ie Ratings : A1 ASL Airlines (Airlines) Ltd. T/A Air Contractors Approval No. IE.145.024 3 Malahide Road Swords Co. Dublin Tel: 01 812 1900 Fax: 01 812 1919 Ratings : A1 Aircraft Components & Interiors, ATA 25 Approval No. IE.145.058 Castletown Tara Garlow Cross Navan Co.Meath Ireland Tel: 046 902 5592 Ratings: C6 Atlantic Aviation Group Ltd. -

Air Transport Industry

ANALYSIS OF THE EU AIR TRANSPORT INDUSTRY Final Report 2004 Contract no: TREN/05/MD/S07.52077 By Cranfield University CONTENTS GLOSSARY...........................................................................................................................................................6 1. AIR TRANSPORT INDUSTRY OVERVIEW ..................................................................................12 2. REGULATORY DEVELOPMENTS .................................................................................................18 3. CAPACITY ...........................................................................................................................................24 4. AIR TRAFFIC ......................................................................................................................................36 5. AIRLINE FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE .......................................................................................54 6. AIRPORTS............................................................................................................................................86 7. AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL ...............................................................................................................104 8. THE ENVIRONMENT......................................................................................................................114 9. CONSUMER ISSUES ........................................................................................................................118 10 AIRLINE ALLIANCES.....................................................................................................................126 -

Air Transport: Annual Report 2005

ANALYSIS OF THE EU AIR TRANSPORT INDUSTRY Final Report 2005 Contract no: TREN/05/MD/S07.52077 by Cranfield University Department of Air Transport Analysis of the EU Air Transport Industry, 2005 1 CONTENTS 1 AIR TRANSPORT INDUSTRY OVERVIEW......................................................................................11 2 REGULATORY DEVELOPMENTS.....................................................................................................19 3 CAPACITY ............................................................................................................................................25 4. AIR TRAFFIC........................................................................................................................................36 5. AIRLINE FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE............................................................................................54 6. AIRPORTS.............................................................................................................................................85 7 AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL ..................................................................................................................102 8. THE ENVIRONMENT ........................................................................................................................110 9 CONSUMER ISSUES..........................................................................................................................117 10 AIRLINE ALLIANCES .......................................................................................................................124 -

The Business Case Concerning the Proposed Acquisition of Connemara Airport by the Contracting Authority

The Business Case concerning the proposed acquisition of Connemara Airport by the Contracting Authority (in accordance with the terms of the Public Spending Code) August 2019 Contents 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 3 Approach to the Appraisal ........................................................................................................ 3 Report Status .............................................................................. Error! Bookmark not defined. 2. Preliminary Appraisal ........................................................................................................ 4 3. Detailed Appraisal ........................................................................................................... 30 Multi-criteria Analysis, Valuation and Potential Revenue Generation and Cost Savings .... 31 4. Multi Criteria (MCA) Analysis ......................................................................................... 32 5. Financial Appraisal .......................................................................................................... 35 Financial Modelling Process .................................................................................................... 35 6. Sensitivity Testing - Multi Criteria Analysis and Financial Appraisal ............................ 40 Managing Asset-Specific risks ............................................................................................. 43 Cost -

List of EU Air Carriers Holding an Active Operating Licence

Active Licenses Operating licences granted Member State: Austria Decision Name of air carrier Address of air carrier Permitted to carry Category (1) effective since ABC Bedarfsflug GmbH 6020 Innsbruck - Fürstenweg 176, Tyrolean Center passengers, cargo, mail B 16/04/2003 AFS Alpine Flightservice GmbH Wallenmahd 23, 6850 Dornbirn passengers, cargo, mail B 20/08/2015 Air Independence GmbH 5020 Salzburg, Airport, Innsbrucker Bundesstraße 95 passengers, cargo, mail A 22/01/2009 Airlink Luftverkehrsgesellschaft m.b.H. 5035 Salzburg-Flughafen - Innsbrucker Bundesstraße 95 passengers, cargo, mail A 31/03/2005 Alpenflug Gesellschaft m.b.H.& Co.KG. 5700 Zell am See passengers, cargo, mail B 14/08/2008 Altenrhein Luftfahrt GmbH Office Park 3, Top 312, 1300 Wien-Flughafen passengers, cargo, mail A 24/03/2011 Amira Air GmbH Wipplingerstraße 35/5. OG, 1010 Wien passengers, cargo, mail A 12/09/2019 Anisec Luftfahrt GmbH Office Park 1, Top B04, 1300 Wien Flughafen passengers, cargo, mail A 09/07/2018 ARA Flugrettung gemeinnützige GmbH 9020 Klagenfurt - Grete-Bittner-Straße 9 passengers, cargo, mail A 03/11/2005 ART Aviation Flugbetriebs GmbH Porzellangasse 7/Top 2, 1090 Wien passengers, cargo, mail A 14/11/2012 Austrian Airlines AG 1300 Wien-Flughafen - Office Park 2 passengers, cargo, mail A 10/09/2007 Disclaimer: The table reflects the data available in ACOL-database on 16/10/2020. The data is provided by the Member States. The Commission does not guarantee the accuracy or the completeness of the data included in this document nor does it accept responsibility for any use made thereof. 1 Active Licenses Decision Name of air carrier Address of air carrier Permitted to carry Category (1) effective since 5020 Salzburg-Flughafen - Innsbrucker Bundesstraße AVAG AIR GmbH für Luftfahrt passengers, cargo, mail B 02/11/2006 111 Avcon Jet AG Wohllebengasse 12-14, 1040 Wien passengers, cargo, mail A 03/04/2008 B.A.C.H. -

European Hub Airports – Assessment of Constraints for Market Power in the Local Catchment and on the Transfer Market

Technische Universität Dresden Fakultät Verkehrswissenschaften „Friedrich List” Institut für Wirtschaft und Verkehr DISSERTATION European Hub Airports – Assessment of Constraints for Market Power in the Local Catchment and on the Transfer Market zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doctor rerum politicarum (Dr. rer. pol.) im Rahmen des Promotionsverfahrens an der Fakultät Verkehrswissenschaften „Friedrich List“ der Technischen Universität Dresden vorgelegt von: Annika Paul, geb. Reinhold geb. am 30.09.1981 in Gifhorn Gutachter: Prof. Dr. rer. pol. habil. Bernhard Wieland Prof. Dr. rer. pol. Hans-Martin Niemeier Ort und Tage der Einreichung: Dresden, 23. Januar 2018 Ort und Tag der Verteidigung: Dresden, 04. Juni 2018 Abstract Airports have long been considered as an industry in which firms are able to exert significant market power. Nowadays, there is controversial discussion whether airports face a degree of competition which is sufficient to constrain potentially abusive behaviour resulting from this market power. The level of competition encountered by European airports has hence been evaluated by analysing the switching potential of both airlines and passengers between different airports, for example. The research within this thesis contributes to the field of airport competition by analysing the degree of potential competition 36 European hub airports face on their origin-destination market in their local catchments as well as on the transfer market within the period from 2000 to 2016. For this purpose, a two-step approach is applied for each market, with first analysing the degree of market concentration, using the Herfindahl Hirschman Index as a measure, for each destination offered at the hub airports and the respective development over time. -

March 2017 Newsletter

BNAPS News March 2017 BNAPS News Vol 7 Iss 2 – March 2017 BN Islander no. 3 G-AVCN - First Flight 50th Special Edition 2017 – Islander G-AVCN’s Restoration Completion First Flight and Production Delivery 50th View of Islander G-AVCN in Glos Air colours over Tennyson Down, Isle of Wight 50 years on from its first flight on 24 April, 1967, BN Islander cn 3, G-AVCN, will emerge in 2017 as a high quality static restoration some 17 years after it was recovered from Isla Grande Airport in Puerto Rico. The remarkable history of Islander cn 3 is the subject of a feature article starting on page 10. G-AVCN’s First Flight 50th Anniversary Celebration 1000 to 1200 at the Propeller Inn, Bembridge Airport on Saturday 22 April, 2017 Workshop tours in the afternoon All are welcome to attend – Contact BNAPS for details Opportunity to win the “First of the Many” original painting and prints in BNAPS April 2017 Fund Raising Draw- For details see page 2 1 BNAPS Supporters Fund Raising Appeal - March 2017 2017 2010 2016 Dear BNAPS Supporter, Thanks to a number of generous donations the financial situation has shown an improvement. However, there is still some way to go to provide the required cover for the restoration project in 2017 and to ensure safekeeping for our restored Islander G-AVCN. The fund raising appeal continues and goes out to all BNAPS Supporters and friends to ask for more help through individual or regular donations. If you would like to support the fund raising appeal please contact BNAPS by e mail [email protected] or Telephone 01329 315561. -

REVIEW of AVIATION SAFETY PERFORMANCE in IRELAND DURING 2017 Front Cover: an Aer Lingus Airbus 330 Being Prepared for Flight at Dublin Airport

REVIEW OF AVIATION SAFETY PERFORMANCE IN IRELAND DURING 2017 Front cover: An Aer Lingus Airbus 330 being prepared for flight at Dublin airport. Photographer Paul Kolbe-Hurley. This page: The DJI Inspire being displayed at the Bray International Airshow in July 2017. Photographer Jason Phelan. Contents Foreword 2 Number and rate of MORs: 2013 - 2017 ...........................................19 Number and rate of aerodromes MORs during Comparison of MOR, accident and serious incident 2016 and 2017 ................................................................................................37 Executive Summary 3 rate with European counterparts .................................................... 20 2016 and 2017 Aerodrome MORs: Categorisation Occurrence categories and ARMS score and ARMS score assigned .................................................................... 38 assigned to MORs: 2017 ......................................................................... 20 Infographics 4 For comparison with 2017: Occurrence categories and Section E: General Aviation 40 ARMS score assigned to MORs between 2013 - 2016 .............22 Scope of Analysis and Sources of Data .........................................41 Section A: Safety in the Irish Aviation Industry 10 Voluntary occurrence reporting .........................................................24 Voluntary Occurrence Reporting .......................................................41 The Irish Aviation Authority ................................................................. 11 -

DAA Resulting from Determination

21st June 2007 Response to Draft Decision Interim Review of 2005 Determination on Maximum Levels of Airport Charges at Dublin Airport. 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary ..........................................................................................................4 1. Introduction ...............................................................................................................9 2. Regulatory Risk.......................................................................................................10 2.1 Steps Other Regulators Take to Reduce Risk ......................................................10 2.2 Recommendations for CAR Approach to Regulatory Risk....................................13 2.2.1 Cost of Capital Premium ................................................................................13 2.2.2 Improving Regulatory Commitment and Reducing Investment Risks ............13 3. Financeability ..........................................................................................................15 3.1 Summary...............................................................................................................15 Financial projections and future FFO / Debt ratios..................................................15 3.2 Financeability and Credit Ratios ...........................................................................16 3.3 Increased business risks for DAA resulting from determination............................17 3.4 Regulatory risk and uncertainty over future regulatory periods.............................18 -

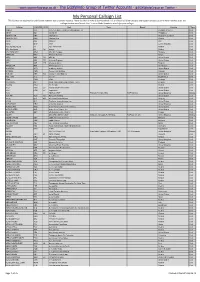

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type AASCO KAA Asia Aero Survey and Consulting Engineers Republic of Korea Civil ABAIR BOI Aboitiz Air Philippines Civil ABAKAN AIR NKP Abakan Air Russian Federation Civil ABAKAN-AVIA ABG Abakan-Avia Russia Civil ABAN ABE Aban Air Iran Civil ABAS MRP Abas Czech Republic Civil ABC AEROLINEAS AIJ ABC Aerolíneas Mexico Civil ABC Aerolineas AIJ 4O Interjet Mexico Civil ABC HUNGARY AHU ABC Air Hungary Hungary Civil ABERDAV BDV Aberdair Aviation Kenya Civil ABEX ABX GB ABX Air United States Civil ABEX ABX GB Airborne Express United States Civil ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ABSOLUTE AKZ AK Navigator LLC Kazakhstan Civil ACADEMY ACD Academy Airlines United States Civil ACCESS CMS Commercial Aviation Canada Civil ACE AIR AER KO Alaska Central Express United States Civil ACE TAXI ATZ Ace Air South Korea Civil ACEF CFM ACEF Portugal Civil ACEFORCE ALF Allied Command Europe (Mobile Force) Belgium Civil ACERO ARO Acero Taxi Mexico Civil ACEY ASQ EV Atlantic Southeast Airlines United States Civil ACEY ASQ EV ExpressJet United States Civil ACID 9(B)Sqn | RAF Panavia Tornado GR4 RAF Marham United Kingdom Military ACK AIR ACK DV Nantucket Airlines United States Civil ACLA QCL QD Air Class Líneas Aéreas Uruguay Civil ACOM ALC Southern Jersey Airways, Inc.