Chapter 1 Chapter 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sociolinguistic Study of Bareli/Pauri and Related Languages

DigitalResources Electronic Survey Report 2018-011 A Sociolinguistic Study of Bareli/Pauri and Related Languages Vinod Wilson Varkey and Kishore Kumar Vunnamatla A Sociolinguistic Study of Bareli/Pauri and Related Languages Vinod Wilson Varkey and Kishore Kumar Vunnamatla SIL International® 2018 SIL Electronic Survey Report 2018-011, August 2018 © 2018 SIL International® All rights reserved Data and materials collected by researchers in an era before documentation of permission was standardized may be included in this publication. SIL makes diligent efforts to identify and acknowledge sources and to obtain appropriate permissions wherever possible, acting in good faith and on the best information available at the time of publication. Abstract This report describes a sociolinguistic study of the languages spoken by the Barela/Paura, Bhilala and Bhil people, living in the border districts of southwest Madhya Pradesh and northwest Maharashtra. The main focus is placed on the Barelas/Pauras. The project began in July 1998 with two weeks of background research and reviewing previous survey reports. The fieldwork was carried out in the period from September to December 1998 at over 20 locations. The report first describes the geography of the area in which the survey was conducted and the people groups who speak the Bareli/Pauri language. The similarity between dialects of the language was assessed through a lexical similarity comparison. Intelligibility testing was likewise conducted. Conclusions about the linguistic similarity of dialects are given in section 2 of the report. Bilingualism in Hindi, Nimadi and Ahirani were assessed and conclusions are drawn in section 3. Questionnaires were conducted to assess language vitality. -

State City Hospital Name Address Pin Code Phone K.M

STATE CITY HOSPITAL NAME ADDRESS PIN CODE PHONE K.M. Memorial Hospital And Research Center, Bye Pass Jharkhand Bokaro NEPHROPLUS DIALYSIS CENTER - BOKARO 827013 9234342627 Road, Bokaro, National Highway23, Chas D.No.29-14-45, Sri Guru Residency, Prakasam Road, Andhra Pradesh Achanta AMARAVATI EYE HOSPITAL 520002 0866-2437111 Suryaraopet, Pushpa Hotel Centre, Vijayawada Telangana Adilabad SRI SAI MATERNITY & GENERAL HOSPITAL Near Railway Gate, Gunj Road, Bhoktapur 504002 08732-230777 Uttar Pradesh Agra AMIT JAGGI MEMORIAL HOSPITAL Sector-1, Vibhav Nagar 282001 0562-2330600 Uttar Pradesh Agra UPADHYAY HOSPITAL Shaheed Nagar Crossing 282001 0562-2230344 Uttar Pradesh Agra RAVI HOSPITAL No.1/55, Delhi Gate 282002 0562-2521511 Uttar Pradesh Agra PUSHPANJALI HOSPTIAL & RESEARCH CENTRE Pushpanjali Palace, Delhi Gate 282002 0562-2527566 Uttar Pradesh Agra VOHRA NURSING HOME #4, Laxman Nagar, Kheria Road 282001 0562-2303221 Ashoka Plaza, 1St & 2Nd Floor, Jawahar Nagar, Nh – 2, Uttar Pradesh Agra CENTRE FOR SIGHT (AGRA) 282002 011-26513723 Bypass Road, Near Omax Srk Mall Uttar Pradesh Agra IIMT HOSPITAL & RESEARCH CENTRE Ganesh Nagar Lawyers Colony, Bye Pass Road 282005 9927818000 Uttar Pradesh Agra JEEVAN JYOTHI HOSPITAL & RESEARCH CENTER Sector-1, Awas Vikas, Bodla 282007 0562-2275030 Uttar Pradesh Agra DR.KAMLESH TANDON HOSPITALS & TEST TUBE BABY CENTRE 4/48, Lajpat Kunj, Agra 282002 0562-2525369 Uttar Pradesh Agra JAVITRI DEVI MEMORIAL HOSPITAL 51/10-J /19, West Arjun Nagar 282001 0562-2400069 Pushpanjali Hospital, 2Nd Floor, Pushpanjali Palace, -

Brirf Indusstrial Profile of Dhule District

Brirf Indusstrial Profile of Dhule District Contents S.No. Topic Page No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 1 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 1 1.2 Climate 1 1.3 Rain Fall 1 1.4 Soil 1 1.5 Rivers 2 1.6 Availability of Minerals 2 1.7 Forest 2 1.8 Population 3 1.9 Occupational Structure 3 2.0 Administrative set up 3 2. District at a glance 4 2.1 Existing status of Industrial area in the district 6 3. Industrial scenario of Nashik district 6 3.1 Industry at a Glance 6 3.2 Year wise trend of units registered 6 3.3 Details of existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan units 7 in the district 3.4 Large Scale Industries 8 3.5 Major exportable items 10 3.6 Growth Trend 10 3.7 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 10 3.8 List of Medium Scale Enterprises 10 3.8.1 Major Exportable items 10 3.9 List of Potential Enterprises - MSMEs 11 3.9.1 Agro Based Industry 11 3.9.2 Forest Based Industry 11 3.9.3 Demand Based Industry 11 3.9.4 Technical Skilled Based Industries/Services 12 3.9.5 Service Industries 12 4. Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprise 13 4.1 Detail of major clusters 13 4.1.1 Manufacturing sector 13 4.2 Details of clusters identified & selected under MSE-CDP 13 4.2.1 Fiber to Fabrics Cluster, Shirpur, Dhule 13 5. General issues raised by Industries Association 14 6. Steps to set up MSMEs - 15 Brief Industrial Profile of Dhule District 1) General Characteristics Of The District: In olden days, Khandesh was known as Kanha Desh, which means Lord Shreekrishna’s Desh. -

Annexure-V State/Circle Wise List of Post Offices Modernised/Upgraded

State/Circle wise list of Post Offices modernised/upgraded for Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Annexure-V Sl No. State/UT Circle Office Regional Office Divisional Office Name of Operational Post Office ATMs Pin 1 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA PRAKASAM Addanki SO 523201 2 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL KURNOOL Adoni H.O 518301 3 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM AMALAPURAM Amalapuram H.O 533201 4 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Anantapur H.O 515001 5 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Machilipatnam Avanigadda H.O 521121 6 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA TENALI Bapatla H.O 522101 7 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Bhimavaram Bhimavaram H.O 534201 8 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA Buckinghampet H.O 520002 9 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL TIRUPATI Chandragiri H.O 517101 10 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Prakasam Chirala H.O 523155 11 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CHITTOOR Chittoor H.O 517001 12 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CUDDAPAH Cuddapah H.O 516001 13 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM VISAKHAPATNAM Dabagardens S.O 530020 14 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL HINDUPUR Dharmavaram H.O 515671 15 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA ELURU Eluru H.O 534001 16 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudivada Gudivada H.O 521301 17 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudur Gudur H.O 524101 18 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Guntakal H.O 515801 19 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA -

Educational Development Index Maharashtra 2011-12

Educational Development Index Maharashtra 2011-12 December, 2012 Contents S.No. Subject Page number 1.0 Background and Methodology 3 2.0 Status of Maharashtra state at National level in EDI 4 3.0 EDI calculation in Maharashtra state 7 4.0 Analysis of district wise Educational Development Index (EDI), 2011-12 8 5.0 Analysis of block wise Educational Development Index (EDI), 2011-12 14 6.0 Analysis of Municipal Corporation wise Educational Development Index (EDI), 20 2011-12 Annex-1 : Key educational indicators by Districts, 2011-12 23 Annex-2 : Index value and ranking by Districts, 2011-12 25 Annex-3 : Key educational indicators by blocks, 2011-12 27 Annex-4 : Index value and ranking by blocks, 2011-12 45 Annex-5 : Key educational indicators by Municipal Corporations , 2011-12 57 Annex-6 : Index value and ranking by Municipal Corporations, 2011-12 58 Educational Development Index, 2011-12, Maharashtra Page 1 Educational Development Index, 2011-12, Maharashtra 1.0 Background and Methodology: Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD), Government of India and the National University of Educational Planning and Administration (NUEPA), New Delhi initiated an effort to compute Educational Development Index (EDI).In year 2005-06, MHRD constituted a working group to suggest a methodology (which got revised in 2009)for computing EDI. The purpose of EDI is to summarize various aspects related to input, process and outcome indicators and to identify geographical areas that lag behind in the educational development. EDI is an effective tool for decision making, i.e. it helps in identifying backward geographical areas where more focus is required. -

Registration Details of Geographical Indications

REGISTRATION DETAILS OF GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS Goods S. Application Geographical Indications (As per Sec 2 (f) State No No. of GI Act 1999 ) FROM APRIL 2004 – MARCH 2005 Darjeeling Tea (word & 1 1 & 2 Agricultural West Bengal logo) 2 3 Aranmula Kannadi Handicraft Kerala 3 4 Pochampalli Ikat Handicraft Telangana FROM APRIL 2005 – MARCH 2006 4 5 Salem Fabric Handicraft Tamil Nadu 5 7 Chanderi Sarees Handicraft Madhya Pradesh 6 8 Solapur Chaddar Handicraft Maharashtra 7 9 Solapur Terry Towel Handicraft Maharashtra 8 10 Kotpad Handloom fabric Handicraft Odisha 9 11 Mysore Silk Handicraft Karnataka 10 12 Kota Doria Handicraft Rajasthan 11 13 & 18 Mysore Agarbathi Manufactured Karnataka 12 15 Kancheepuram Silk Handicraft Tamil Nadu 13 16 Bhavani Jamakkalam Handicraft Tamil Nadu 14 19 Kullu Shawl Handicraft Himachal Pradesh 15 20 Bidriware Handicraft Karnataka 16 21 Madurai Sungudi Handicraft Tamil Nadu 17 22 Orissa Ikat Handicraft Odisha 18 23 Channapatna Toys & Dolls Handicraft Karnataka 19 24 Mysore Rosewood Inlay Handicraft Karnataka 20 25 Kangra Tea Agricultural Himachal Pradesh 21 26 Coimbatore Wet Grinder Manufactured Tamil Nadu 22 28 Srikalahasthi Kalamkari Handicraft Andhra Pradesh 23 29 Mysore Sandalwood Oil Manufactured Karnataka 24 30 Mysore Sandal soap Manufactured Karnataka 25 31 Kasuti Embroidery Handicraft Karnataka Mysore Traditional 26 32 Handicraft Karnataka Paintings 27 33 Coorg Orange Agricultural Karnataka 1 FROM APRIL 2006 – MARCH 2007 28 34 Mysore Betel leaf Agricultural Karnataka 29 35 Nanjanagud Banana Agricultural -

At Glance Nashik Division

At glance Nashik Division Nashik division is one of the six divisions of India 's Maharashtra state and is also known as North Maharashtra . The historic Khandesh region covers the northern part of the division, in the valley of theTapti River . Nashik Division is bound by Konkan Division and the state of Gujarat to the west, Madhya Pradesh state to the north, Amravati Division and Marathwada (Aurangabad Division) to the east, andPune Division to the south. The city of Nashik is the largest city of this division. • Area: 57,268 km² • Population (2001 census): 15,774,064 • Districts (with 2001 population): Ahmednagar (4,088,077), Dhule (1,708,993), Jalgaon (3,679,93 6) Nandurbar (1,309,135), Nashik 4,987,923 • Literacy: 71.02% • Largest City (Population): Nashik • Most Developed City: Nashik • City with highest Literacy rate: Nashik • Largest City (Area): Nashik * • Area under irrigation: 8,060 km² • Main Crops: Grape, Onion, Sugarcane, Jowar, Cotton, Banana, Chillies, Wheat, Rice, Nagli, Pomegranate • Airport: Nasik [flights to Mumbai] Gandhinagar Airport , Ozar Airport • Railway Station:Nasik , Manmad , Bhusaval History of administrative districts in Nashik Division There have been changes in the names of Districts and has seen also the addition of newer districts after India gained Independence in 1947 and also after the state of Maharashtra was formed. • Notable events include the creation of the Nandurbar (Tribal) district from the western and northern areas of the Dhule district. • Second event include the renaming of the erstwhile East Khandesh district as Dhule , district and West Khandesh district as Jalgaon . • The Nashik district is under proposal to be divided and a separate Malegaon District be carved out of existing Nashik district with the inclusion of the north eastern parts of Nashik district which include Malegaon , Nandgaon ,Chandwad ,Deola , Baglan , and Kalwan talukas in the proposed Malegaon district. -

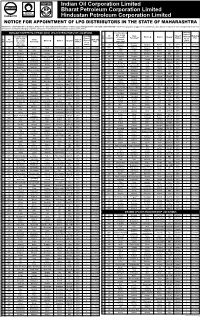

Indian Oil Corporation Limited Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Limited

Indian Oil Corporation Limited Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Limited NOTICE FOR APPOINTMENT OF LPG DISTRIBUTORS IN THE State OF MAHARASHTRA INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD (IOCL), BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LTD (BPCL) and HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM CORPORATION LTD (HPCL) proposes to appoint LPG distributors under various categories at locations specified below from amongst the candidates belonging to different categories mentioned therein in the State of (name of the State): DURGAM KSHETRIYA VITRAK (DKV) LPG DISTRIBUTORSHIP LOCATIONS Location (along Security with details Deposit Security Sr. Oil Gram Type of Marketing Location (along of Locality Block* @ District Category** (Amount Deposit No. Company Panchayat* Market Plan with details wherever Rs. in Sr. Oil Gram Type of (Amount Marketing of Locality Block* @ District Category** applicable) Lakhs) No. Company Panchayat* Market Rs. in Plan wherever Chinchave Chinchave Lakhs) 96 IOC Malegaon Nashik SC 2 2017-18 applicable) (Galane) (Galane) DKV 1 IOC Khirvire Khirvire Akole Ahmednagar Open DKV 4 2017-18 97 HPC Nimgaon Nimgaon Malegaon Nashik Open(W) DKV 4 2017-18 2 IOC Hatru Hatru Chikhaldara Amravati OBC DKV 3 2017-18 98 IOC Tingri Tingri Malegaon Nashik Open DKV 4 2017-18 3 IOC Ghodgaon Ghodgaon Chopda Jalgaon ST DKV 2 2017-18 99 BPC Vehelgaon Vehelgaon Nandgaon Nashik OBC DKV 3 2017-18 4 BPC Ghuikhed Ghuikhed Chandur Railway Amravati Open DKV 4 2017-18 100 IOC Thangaon Thangaon Sinnar Nashik ST(W) DKV 2 2017-18 5 IOC Jalalkheda Jalalkheda Narkhed Nagpur -

District Census Handbook, Dhule

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK DHULE Compiled by THE MAHARASlITRA CENSUS DIRECTORATE BOMBAY Price : Rs. 30.00 PRINTED IN INDIA BY THE MANAGER. YERA VDA PRISON PRESS, PUNE AND PUBLISHED BY THE DIRECTOR, GOVERNMENT PRINTING AND STATIONERY, MAHARASHTRA STATE, BOMBAY-400 004 1985 '": ~co ":;: 0 • u © • 0 B .~ .g Q: :r • cr "0 @ I '1 1: >: 1~ '" I w '" " .....J . 0 • ~ ~ e 0 ::> I c '"~ <l: 0 · ::I: e i 0 a:: Ol 0 0- g~ 2" 0 z." ] ~ I ." DC Vl .2 0 Q ; 0 0 ~ ~ 0 0 1j <l: cr 0 :l"Pj "0 .c C ~ .. t- g ~ a:: 0 ~ ,. .c § ;~ <l: 0 6 ,. E '" I U ~ ~ ~ ~ 0 ~ ~ Vi < B-1 <l: . ! ~ ; ~ · Vi 0> ~ i < . ~~ ~ ;3 0 cr I C "0 · ~ C 2 ~ ·0 ~ 0 i 0 0";' x· t- s ('; c. 0 0 ~ . o • If) ,f~ ~2 ·~ t I V> § ;> ~ ~I '" cii Ii: :0" £ a · V> '" 0 ~ 1- " () ..(- /r ,9 tl' 8- 'J Ir J " & J 0 S <:) i" ~ I U- ";, 0 "r % ~ "'(j.\6,;~r§\ ,\oc.: ~'r::/l.O «- po.~tc.~ " ~ .. -:' ..l.. le ~ .:t () If) 'Of <l: <! ~ ... (J 0: 0 ... .£ i, "0 '"" </I 1 <!> ,.0 ~ 0 ~ .> I ':i , l, V> "8" .c ~r·,-- l' "0 .. ,.. i .~ ~ I'. ~ s:::" ~ "0 i'" 1 .c .c ~ "~ " U; 0 " a E ~ 0- ~ l' ::. ] I "0 ~ :r :; Vl . a :;: , VI ~ r e-'" (\ ~~ ..] MOTIF 'The Bhils of Maharashtra are mainly concentrated in Dhule district. They have kng history since ancient times. The earliest mention of their name occurs in the Ramayana and the Maha bharata. Bhils possibly belong 10 a proto Mediterranean race who spread far and wide when a climatic crisis occurred in the gral>s steppes 0 f the Sahara. -

District-Nandurbar No.Of Inmates

District-Nandurbar No.of Inmates In Case of Contact Details & E-mail Year of Establishment of the Nature of management Sr. No. Name of the Institutions & Address Total Present Hostel,no.of ID Institution/ Hostel (Govt.run/aided or Private) Capacity Strength SC/ST/OBC Students Janseva Mandal Ashramshala Korit 1 -- 73 73 73 ST/SC/OBC Private Non-Aidedor Road Nandurbar Tal.Nandurbar -- Jevan Vidya Vastigurha Nandurbar 2 -- 64 64 64 ST/SC/OBC Private Non-Aidedor Tal.Nandurbar -- 3 Mukbadhir Nivasi Vidyhlya Nandurbar -- 40 40 40 ST/SC/OBC Private Aidedor -- Mukbadhir Nivasi Vidyhlya Dudhale 4 -- 50 50 50 ST/SC/OBC Private Non-Aidedor Tal.Nandurbar -- Nivasi Andha shala Dhamadada 5 -- 40 40 40 ST/SC/OBC Private Non-Aidedor Tal.Nandurbar -- S.A.Mission Girls Vastigurha 443 6 -- 443 443 Private Non-Aidedor Tal.Nandurbar ST/SC/OBC S.A.Mission Boys Vastigurha -- 7 -- 644 644 644 ST Private Non-Aidedor Tal.Nandurbar 9822653826 Email- KathobaDev Shikshan Prasarak Mandal, [email protected] Aakrale Tal.Dist.Nandurbar Sanchalit 8 -- 380 380 380 VJNT Private Aidedor V.J.N.T. Secondary Aashramashala and Junior College Aakrale Tal.Nandurbar Sw.Shriram Karnakar Matimand -- 9 -- 25 25 26 Private Aidedor Vidyalaya,Nanurbar Tal.Nandurbar Sane Guruji Chatralaya Nandurbar -- 10 -- 35 35 25 Private Non-Aidedor Tal.Nandurbar -- Sarsvati Kanya Chatralaya Nandurbar 11 -- 31 31 31 ST/SC/OBC Private Aidedor Tal.Nandurbar -- Matimand Mulanche Nivasi Shala Hol 12 -- 30 30 30 ST/SC/OBC Private Aidedor T.Havle Tal.Nandurbar Matimand Muliche Nivasi Shala -- 13 GuruKul -

2015-09-15-Short Note

Date:-15.09.2015 SHORT NOTE Computerization and Modernization of 22+2 Border Check Posts in the State of Maharashtra on BOT Basis Objective :- • Computerization and Modernization of 22+2 Border Check Posts to create fast &transparent Modes operandy of the officers of three departments Transport, Sales Tax and State Excise Departments who will function under one building premises simultaneously. • 100% checking of the vehicle will be possible. • It will enable the concerned drivers/owners to make the payment of the due amount within short time at one place. Approval :- • MSRDC declared as PIA Vide GR dated 25th March, 2008 • Rs 100 crore for land acquisition • Rate of service fee is fixed • Advertisement rights given to Concessionaire Classification of BCP’s :- Classification Number Number of Area Remarks of the BCP lanes on Both required for sides of BCP each BCP Major 03 15-15 15-20 Hect 13 BCPS are under O&M. Big 02 13-13 12-15 Hect 7 BCPs are in progress Medium 07 10-10 12-15 Hect 4 BCPs - L.A. is still under process Small 10+2 07-07 <10Hect As per ROW available 6insitu Total 24 BCPs being constructed till L.A. Scope of the Project: - Construction of BCP at 22+2 locations Category No. No. of Lanes Location Major 3 15+15 Achhad, Navapur, Hadakhed Big 2 13+13 Kagal, Deori Medium 7 10+10 Saoner, Ramtek, Mandrup, Marwade, Pimpalkhunti, Omarga, Insuli Small 10 7+7 Warud, Kharpi, Muktainagar, Biloli, Borgaon, Shinoli, Akkalkuwa, Rajura, Chorwad, Deglur Additional 2 7+7 Kelwad (Chindwada road) BCP and Peth In-situ 6-Out As per availability -

Chapter 4 Profile of North Maharashtra 4

CHAPTER 4 PROFILE OF NORTH MAHARASHTRA 4. 1 Introduction: Profile of Maharashtra The state of Maharashtra is one of the largest state in India. The Indian state of Maharashtra came into existence on 1st May 1960. It is the second state in India in whole of India with respect to population and area wise. As per the census the land area covered by the state of Maharashtra is three lakh eight thousand sq.km. The state has the overall population of 112,372,972 as per 2011 census report. The state covers approximately 9.5 % share of total population of India. Maharashtra continues to be one of the fastest growing states of the Indian union with acceleration in its growth process sustained largely by the secondary and mostly by tertiary sector. Map 4.1 Map of Maharashtra Source: www.marathizataka.blogspot.co updated 2016 77 4.1.1State boundaries The state of Maharashtra is surrounded by the Arabian Sea in the West, Gujarat in the North west, Madhya Pradesh in the in the North, Andhra Pradesh in the Southeast and Karnataka and Goa in the south. 4.1.2 State Capital The state capital of Maharashtra is Mumbai. It is the financial capital of our country. Most of the major corporate offices, head offices are situated in the purview of Mumbai. Almost all the major traders and marketers, Industrial head offices are in and around Mumbai. The financial Institutions largest share is in Mumbai. The country’s Stock exchange and the capital market and commodity exchanges are located in Mumbai.