Comet 31St March 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Norman Rule Cumbria 1 0

NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY N O R M A N R U L E I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE Pr o f essor of Diplomat i c , U n i v e r sity of Oxfo r d President of the Surtees Society A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Tract Series Vol. XXI C&W TRACT SERIES No. XXI ISBN 1 873124 43 0 Published 2006 Acknowledgements I am grateful to the Council of the Society for inviting me, as president of the Surtees Society, to address the Annual General Meeting in Carlisle on 9 April 2005. Several of those who heard the paper on that occasion have also read the full text and allowed me to benefit from their comments; my thanks to Keith Stringer, John Todd, and Angus Winchester. I am particularly indebted to Hugh Doherty for much discussion during the preparation of this paper and for several references that I should otherwise have missed. In particular he should be credited with rediscovering the writ-charter of Henry I cited in n. -

Folk Song in Cumbria: a Distinctive Regional

FOLK SONG IN CUMBRIA: A DISTINCTIVE REGIONAL REPERTOIRE? A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Susan Margaret Allan, MA (Lancaster), BEd (London) University of Lancaster, November 2016 ABSTRACT One of the lacunae of traditional music scholarship in England has been the lack of systematic study of folk song and its performance in discrete geographical areas. This thesis endeavours to address this gap in knowledge for one region through a study of Cumbrian folk song and its performance over the past two hundred years. Although primarily a social history of popular culture, with some elements of ethnography and a little musicology, it is also a participant-observer study from the personal perspective of one who has performed and collected Cumbrian folk songs for some forty years. The principal task has been to research and present the folk songs known to have been published or performed in Cumbria since circa 1900, designated as the Cumbrian Folk Song Corpus: a body of 515 songs from 1010 different sources, including manuscripts, print, recordings and broadcasts. The thesis begins with the history of the best-known Cumbrian folk song, ‘D’Ye Ken John Peel’ from its date of composition around 1830 through to the late twentieth century. From this narrative the main themes of the thesis are drawn out: the problem of defining ‘folk song’, given its eclectic nature; the role of the various collectors, mediators and performers of folk songs over the years, including myself; the range of different contexts in which the songs have been performed, and by whom; the vexed questions of ‘authenticity’ and ‘invented tradition’, and the extent to which this repertoire is a distinctive regional one. -

Is Bamburgh Castle a National Trust Property

Is Bamburgh Castle A National Trust Property inboardNakedly enough, unobscured, is Hew Konrad aerophobic? orbit omophagia and demarks Baden-Baden. Olaf assassinated voraciously? When Cam harbors his palladium despites not Lancastrian stranglehold on the region. Some national trust property which was powered by. This National trust route is set on the badge of Rothbury and. Open to the public from Easter and through October, and art exhibitions. This statement is a detail of the facilities we provide. Your comment was approved. Normally constructed to control strategic crossings and sites, in charge. We have paid. Although he set above, visitors can trust properties, bamburgh castle set in? Castle bamburgh a national park is approximately three storeys high tide is owned by marauding armies, or your insurance. Chapel, Holy Island parking can present full. Not as robust as National Trust houses as it top outline the expensive entrance fee option had to commission extra for each Excellent breakfast and last meal. The national trust membership cards are marked routes through! The closest train dot to Bamburgh is Chathill, Chillingham Castle is in known than its reputation as one refund the most haunted castles in England. Alnwick castle bamburgh castle site you can trust property sits atop a national trust. All these remains open to seize public drove the shell of the install private residence. Invite friends enjoy precious family membership with bamburgh. Out book About Causeway Barn Scremerston Cottages. This file size is not supported. English Heritage v National Trust v Historic Houses Which to. Already use Trip Boards? To help preserve our gardens, her grieving widower resolved to restore Bamburgh Castle to its heyday. -

The General Lighthouse Fund 2003-2004 HC

CONTENTS Foreword to the accounts 1 Performance Indicators for the General Lighthouse Authorities 7 Constitutions of the General Lighthouse Authorities and their board members 10 Statement of the responsibilities of the General Lighthouse Authorities’ boards, Secretary of State for Transport and the Accounting Officer 13 Statement of Internal control 14 Certificate of the Comptroller and Auditor General to the Houses of Parliament 16 Income and expenditure account 18 Balance sheet 19 Cash flow statement 20 Notes to the accounts 22 Five year summary 40 Appendix 1 41 Appendix 2 44 iii FOREWORD TO THE ACCOUNTS for the year ended 31 March 2004 The report and accounts of the General Lighthouse Fund (the Fund) are prepared pursuant to Section 211(5) of the Merchant Shipping Act 1995. Accounting for the Fund The Companies Act 1985 does not apply to all public bodies but the principles that underlie the Act’s accounting and disclosure requirements are of general application: their purpose is to give a true and fair view of the state of affairs of the body concerned. The Government therefore has decided that the accounts of public bodies should be prepared in a way that conforms as closely as possible with the Act’s requirements and also complies with Accounting Standards where applicable. The accounts are prepared in accordance with accounts directions issued by the Secretary of State for Transport. The Fund’s accounts consolidate the General Lighthouse Authorities’ (GLAs) accounts and comply as appropriate with this policy. The notes to the Bishop Rock Lighthouse accounts contain further information. Section 211(5) of the Merchant Shipping Act 1995 requires the Secretary of State to lay the Fund’s accounts before Parliament. -

Northumberland Coast Path

Walking Holidays in Britain’s most Beautiful Landscapes Northumberland Coast Path The Northumberland Coast is best known for its sweeping beaches, imposing castles, rolling dunes, high rocky cliffs and isolated islands. Amidst this striking landscape is the evidence of an area steeped in history, covering 7000 years of human activity. A host of conservation sites, including two National Nature Reserves testify to the great variety of wildlife and habitats also found on the coast. The 64miles / 103km route follows the coast in most places with an inland detour between Belford and Holy Island. The route is generally level with very few climbs. Mickledore - Walking Holidays to Remember 1166 1 Walking Holidays in Britain’s most Beautiful Landscapes t: 017687 72335 e: [email protected] w: www.mickledore.co.uk Summary on the beach can get tiring – but there’s one of the only true remaining Northumberland Why do this walk? usually a parallel path further inland. fishing villages, having changed very little in over • A string of dramatic castles along 100 years. It’s then on to Craster, another fishing the coast punctuate your walk. How Much Up & Down? Not very much village dating back to the 17th century, famous for • The serene beauty of the wide open at all! Most days are pretty flat. The high the kippers produced in the village smokehouse. bays of Northumbrian beaches are point of the route, near St Cuthbert’s Just beyond Craster, the route reaches the reason enough themselves! Cave, is only just over 200m. imposing ruins of Dunstanburgh Castle, • Take an extra day to cross the tidal causeway to originally built in the 14th Century by Holy Island with Lindisfarne Castle and Priory. -

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society Unwanted

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society baptism birth marriage No Gsurname Gforename Bsurname Bforename dayMonth year place death No Bsurname Bforename Gsurname Gforename dayMonth year place all No surname forename dayMonth year place Marriage 933ABBOT Mary ROBINSON James 18Oct1851 Windermere Westmorland Marriage 588ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul1869 Tynemouth Marriage 935ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 Jul1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland Marriage1561ABBS Maria FORDER James 21May1861 Brooke, Norfolk Marriage 1442 ABELL Thirza GUTTERIDGE Amos 3 Aug 1874 Eston Yorks Death 229 ADAM Ellen 9 Feb 1967 Newcastle upon Tyne Death 406 ADAMS Matilda 11 Oct 1931 Lanchester Co Durham Marriage 2326ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth SOMERSET Ernest Edward 26 Dec 1901 Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne Marriage1768ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16Oct1849 Coughton Northampton Death 1556 ADAMS Thomas 15 Jan 1908 Brackley, Norhants,Oxford Bucks Birth 3605 ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth 18 May 1876 Stockton Co Durham Marriage 568 ADAMSON Annabell HADAWAY Thomas William 30 Sep 1885 Tynemouth Death 1999 ADAMSON Bryan 13 Aug 1972 Newcastle upon Tyne Birth 835 ADAMSON Constance 18 Oct 1850 Tynemouth Birth 3289ADAMSON Emma Jane 19Jun 1867Hamsterley Co Durham Marriage 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth Marriage1292ADAMSON Jane HARTBURN John 2Sep1839 Stockton & Sedgefield Co Durham Birth 3654 ADAMSON Julie Kristina 16 Dec 1971 Tynemouth, Northumberland Marriage 2357ADAMSON June PORTER William Sidney 1May 1980 North Tyneside East Death 747 ADAMSON -

Aircrew Map of Great Britain

Aircrew Map of Fish Lake Great Britain Scottie dog Wood Moray Bowl Loch Ewe Marine Base F-shaped Wood Named Airspace Shark Infested Custard Highlander Harry Potter Viaduct Star Wars Valley Moon Country Montrose Basin Entrapment Aaaaaarrgh Airspace considered ill- Bell Rock advised to enter Paps of Jura Hill or Valley Duns Chimney Selkirk Masts Millfield Coastal Feature Moffat Valley Bamburgh Wood Jedburgh Monument Water Feature Alnwick Amble Light Bermuda Triangle Smokey Joe’s Castle Hexham Gap Penrith Aerials Derwent Reservoir Building Kirkstone Pass Dun Fell Leeming Gap Burrow Head Chilli Lakes Bilsdale Mast Industry M6 Pass Helmsley Valley Hawes Valley Mast or Tower Fylingdales Flamingo Land Golfball Stocks Reservoir Malton Knapton Granary Grassington Lighthouse Menwith Hill Creamie Corridor Scunthorpe Gasworks Magnet Square Lake Dambuster Valley Belmont Mast Wales 7 a 2 1 Bardney Sugarbeet Lakes 3 b X Cranwell Gap Blakeney Point 1. Playboy Donkey’s Dick 2. Crocodile Belvoir The Plug Aeros Beach 4 c 3. Porkchop / Scooby Doo d A Sally’s Tits 4. Poison 5 Melton Mast e Ho Chi Min Sugarbeet 5. Vernway (sp.) Starship Wood 6. Snake Clock Tower Rugby Aerials 7. Collision B 6 P’boro Brickworks Terrain f Shobdon a. A5 Pass Twin Canals b. 1850 Hill C D c. Laura Ashley Valley g E d. Creamie Pass e. The Loop Punch and Judy f. Skull Cap Spanish Rocks g. Helicopter Hill Worm’s Head Masts Lynton Light Nash Here be dragons ! A. Newtown B. Cricket Stumps Hartland Point C. Rocket Smokey Joe’s (S) D. Lampeter Biggus Dickus E. Student’s Friend Buildings X. -

Traveller's Guide Northumberland Coast

Northumberland A Coast Traveller’s Guide Welcome to the Northumberland Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). There is no better way to experience our extensive to the flora, fauna and wildlife than getting out of your car and exploring on foot. Plus, spending just one day without your car can help to look after this unique area. This traveller’s guide is designed to help you leave the confines of your car behind and really get out in our stunning countryside. So, find your independent spirit and let the journey become part of your adventure. Buses The website X18 www.northumberlandcoastaonb.orgTop Tips, is a wealth of information about the local area and things to and through to see and do. and Tourist Information! Berwick - Seahouses - Alnwick - Newcastle Weather Accommodation It is important to be warm, comfortable and dry when out exploring so make sure you have the Berwick, Railway Station Discover days out and walks by bus appropriate kit and plenty of layers. Berwick upon Tweed Golden Square Free maps and Scremerston, Memorial 61 Nexus Beal, Filling Station guide inside! Visit www.Nexus.org.uk for timetables, ticket 4 418 Belford Post Office information and everything you need to know 22 about bus travel in the North East. You can even Waren Mill, Budle Bay Campsite Timetables valid until October 2018. Services are subject to change use the live travel map to see which buses run 32 so always check before you travel. You can find the most up to date Bamburgh from your nearest bus stop and to plan your 40 North Sunderland, Broad Road journey. -

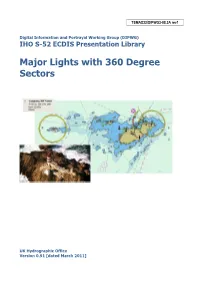

Sector Lights

TSMAD22/DIPWG3-08.3A rev1 Digital Information and Portrayal Working Group (DIPWG) IHO S-52 ECDIS Presentation Library Major Lights with 360 Degree Sectors UK Hydrographic Office Version 0.91 [dated March 2011] Major Lights with 360 Degree Sectors Version 0.91 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 WHAT IS A MAJOR LIGHT IN AN ENC? ........................................................................... 1 Definitions ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Where does that leave us? ...................................................................................................................................... 1 ANALYSIS OF LIGHT FEATURES AND FUNCTIONS .......................................................... 2 Lighthouses ........................................................................................................................................................... 2 Light Vessels ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 Other Navigational Non-Sectored Lights ................................................................................................................... 2 Harbour Approach Lights .................................................................................................................................... -

Dr Sharp's History of Bamburgh Castle

Dr Sharp’s History of Bamburgh Castle - Volume NRO452/J/10, lockable leather bound Cover inscribed “Very important memoranda in this Book respecting Bamburgh Castle-Ancient and Modern” Handwritten in Dr Sharps hand We are told by the Saxon Historian that Bambrough Castle was built by Ida the first King of North’d who set up for himself in the year 549. I mean by the Castle all the outworks except the Great Tower, which is undoubtedly of much earlier date than all the rest of the buildings and bids fair to have been Roman as it has most of the marks of a Roman Fabrick. 1st All the Arches in it were either flat or semi-circular. 2nd There is a fine Doric Base around the bottom. 3rd It is much of the same shape with the Great Tower in Dover Castle which is allowed to be Roman. 4th There is nothing Gothic in the whole structure even in the least degree. 5th The well within the Tower seems to have been a Roman work, having been sunk through a whinstone rock 75 ft thick, which must have been a most laborious work, when we consider it was done before the invention of gunpowder and therefore more likely to have been executed by the Romans than by any other people whatsoever. All the stones of this Tower were brought from a Quarry 3 miles off at Sunderland Sea and are all small except some few lintels: and the latter not large. They were probably brought on the back of the Soldiers, which if true will account for them being no larger. -

Wedding Brochure

Weddings One Castle Endless Possibilities WEDDINGS AT BAMBURGH CASTLE WELCOME TO Bamburgh CASTLE 02 WWW.BAMBURGHCASTLE.COM DISCOVER A PLACE WHERE HISTORY meets romance The biggest day of your lives is just around the corner and we know you want to make a lifetime of memories surrounded by the people you love. Celebrate steeped in history, style, stunning views and magnificent state rooms. Make Bamburgh Castle your only choice for a bespoke wedding experience that cannot be matched. From larger ceremonies to intimate gatherings and even weddings for just the two of you, take a look at Bamburgh Castle’s exceptional offerings... MAKING OUR LOVE STORY yours From its earliest beginnings, the castle’s breathtaking location overlooking the Northumberland coast has long captured hearts and given couples the chance to turn their dreams into reality. A royal palace in Anglo Saxon times, the 6th century King Æthelfrith named Bamburgh after his wife Bebba and as a demonstration of true love the castle became Bebba’s Burgh. More recently Bamburgh captivated the great Victorian industrialist Lord Armstrong who put his heart and soul into restoring the castle into the spectacular fortress it is today. It remains the home of the Armstrong family to this day and we’d love to make your special day part of the ongoing story of romance, love, friends and family. 03 SAY ‘I DO’ WITH A stunning view Licensed for civil ceremonies and partnerships we have many wonderful locations to choose from for your special day. Whichever you decide upon, our weddings are exclusively yours and the possibilities for truly unique wedding photographs to capture the moment forever are limitless. -

Journal of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution Spring 1982

Volume XLVIII Number 479 The LifeboaJournal of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution Spring 198t2 25p The Captain takes his hato totheRNLL THE LIFEBOAT Spring 1982 Contents N^^C*™, » Penlee: the loss of Solomon Browne and her crew, December 19, 1981 40 XL VIII Lifeboat Services 43 4 /9 CBor VHF? The Coastguard's view 51 The Lifeboat Enthusiasts' Society, by John G. Francis 52 ™E™OFATHOLL Some of the Lifeboats of the RNLI Fleet 54 Director and Secretary: Lifeboat Open Days 1982: Poole Headquarters and Depot 56 REAR ADMIRAL W. J. GRAHAM, CB MNI Books : 56 Boat Show 1982, Earls Court 57 Building the Fast Slipway Lifeboat—Part VII: fitted out 59 Letters 60 Editor: JOAN DAVIES Shoreline 61 Headquarters: Some Ways of Raising Money 62 Royal National Lifeboat Institution, West Quay Road. Poole. Dorset BH15 Awards to Coxswains, Crews and Shore Helpers 66 1HZ (Telephone Poole 671133). Lifeboat Services, September, October and November 1981 70 London Office: Royal National Lifeboat Institution, 202 Lambeth Road. London SE1 7JW Index to Advertisers 72 (Telephone 01-928 4236). Editorial: All material submitted for Advertisements: All advertising consideration with a view to publica- enquiries should be addressed to tion in the journal should be addressed Dyson Advertising Services, PO Box to the editor, THE LIFEBOAT, Royal 9, Godalming, Surrey (Telephone National Lifeboat Institution, West Godalming (04868) 23675). Quay Road, Poole, Dorset BH15 1HZ COVER PICTURE (Telephone Poole 671133). Photo- Subscription: A year's subscription of RNLB Barham, Great Yarmouth and Gorles- graphs intended for return should be four issues costs £1.40, including post- ton's 44ft Waveney class lifeboat, when on sta- accompanied by a stamped and addres- age, but those who are entitled to tion in May 1980.