The Frequency of Polyploid Speciation in Vascular Plants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gigas Effect: a Reliable Predictor of Ploidy? Case Studies in Oxalis

The gigas effect: A reliable predictor of ploidy? Case studies in Oxalis by Frederik Willem Becker Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Faculty of Science at Stellenbosch University Supervisors: Prof. Léanne L.Dreyer, Dr. Kenneth C. Oberlander, Dr. Pavel Trávníček March 2021 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2021 …………………………. ………………… F.W. Becker Date Copyright © 2021 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract Whole Genome Duplication (WGD), or polyploidy is an important evolutionary process, but literature is divided over its long-term evolutionary potential to generate diversity and lead to lineage divergence. WGD often causes major phenotypic changes in polyploids, of which the most prominent is the Gigas effect. The Gigas effect refers to the enlargement of plant cells due to their increased amount of DNA, causing plant organs to enlarge as well. This enlargement has been associated with fitness advantages in polyploids, enabling them to successfully establish and persist, eventually causing speciation. Using Oxalis as a study system, I examine whether Oxalis polyploids exhibit the Gigas effect using 24 species across the genus from the Oxalis living research collection at the Stellenbosch University Botanical Gardens, Stellenbosch. -

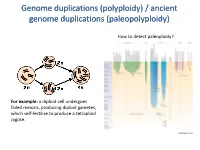

Polyploidy) / Ancient Genome Duplications (Paleopolyploidy

Genome duplications (polyploidy) / ancient genome duplications (paleopolyploidy) How to detect paleoploidy? For example: a diploid cell undergoes failed meiosis, producing diploid gametes, which self-fertilize to produce a tetraploid zygote. Timing of duplication by trees (phylogenetic timing) Phylogenetic timing of duplicates b Paramecium genome duplications Comparison of two scaffolds originating from a common ancestor at the recent WGD Saccharomyces cerevisiae Just before genome duplication Just after genome duplication More time after genome duplication Unaligned view (removing gaps just like in cerev has occurred) Saccharomyces cerevisiae Problem reciprocal gene loss (extreme case); how to solve? Problem reciprocal gene loss (extreme case); how to solve? Just before genome duplication Outgroup! Just after genome duplication Outgroup Just after genome duplication Outgroup More time after genome duplication Outgroup Problem (extreme case); how to solve? Outgroup Outgroup Outgroup Outgroup Outgroup Using other genomes Wong et al. 2002 PNAS Centromeres Vertebrate genome duplication Nature. 2011 Apr 10. [Epub ahead of print] Ancestral polyploidy in seed plants and angiosperms. Jiao Y, Wickett NJ, Ayyampalayam S, Chanderbali AS, Landherr L, Ralph PE, Tomsho LP, Hu Y, Liang H, Soltis PS, Soltis DE, Clifton SW, Schlarbaum SE, Schuster SC, Ma H, Leebens-Mack J, Depamphilis CW. Flowering plants Flowering MOSS Vertebrates Teleosts S. serevisiae and close relatives Paramecium Reconstructed map of genome duplications allows unprecedented mapping -

The Diversity of Plant Sex Chromosomes Highlighted Through Advances in Genome Sequencing

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review The Diversity of Plant Sex Chromosomes Highlighted through Advances in Genome Sequencing Sarah Carey 1,2 , Qingyi Yu 3,* and Alex Harkess 1,2,* 1 Department of Crop, Soil, and Environmental Sciences, Auburn University, Auburn, AL 36849, USA; [email protected] 2 HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology, Huntsville, AL 35806, USA 3 Texas A&M AgriLife Research, Texas A&M University System, Dallas, TX 75252, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (Q.Y.); [email protected] (A.H.) Abstract: For centuries, scientists have been intrigued by the origin of dioecy in plants, characterizing sex-specific development, uncovering cytological differences between the sexes, and developing theoretical models. Through the invention and continued improvements in genomic technologies, we have truly begun to unlock the genetic basis of dioecy in many species. Here we broadly review the advances in research on dioecy and sex chromosomes. We start by first discussing the early works that built the foundation for current studies and the advances in genome sequencing that have facilitated more-recent findings. We next discuss the analyses of sex chromosomes and sex-determination genes uncovered by genome sequencing. We synthesize these results to find some patterns are emerging, such as the role of duplications, the involvement of hormones in sex-determination, and support for the two-locus model for the origin of dioecy. Though across systems, there are also many novel insights into how sex chromosomes evolve, including different sex-determining genes and routes to suppressed recombination. We propose the future of research in plant sex chromosomes should involve interdisciplinary approaches, combining cutting-edge technologies with the classics Citation: Carey, S.; Yu, Q.; to unravel the patterns that can be found across the hundreds of independent origins. -

Reproductive Isolation of Two Sympatric Louseworts, Pedicularis

Blackwell Publishing LtdOxford, UKBIJBiological Journal of the Linnean Society0024-4066© 2006 The Linnean Society of London? 2006 90? 3748 Original Article REPRODUCTIVE ISOLATION IN SYMPATRIC LOUSEWORTS C.-F. YANG ET AL . Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2007, 90, 37–48. With 4 figures Reproductive isolation of two sympatric louseworts, Pedicularis rhinanthoides and Pedicularis longiflora (Orobanchaceae): how does the same pollinator type avoid interspecific pollen transfer? CHUN-FENG YANG, ROBERT W. GITURU† and YOU-HAO GUO* College of Life Sciences, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430072, People’s Republic of China Received 11 April 2005; accepted for publication 1 March 2006 To study the isolation mechanism of two commonly intermingled louseworts, Pedicularis rhinanthoides and Pedic- ularis longiflora, pollination biology in three mixed populations with the two species was investigated during a 3- year project. The results indicated that higher flowering density could help to enhance pollinator activity, and thus increase reproductive output. Bumblebees are the exclusive pollinator for the two louseworts and are essential for their reproductive success. Reproductive isolation between the two species is achieved by a combination of pre- and postzygotic isolation mechanisms. Although both species are pollinated by bumblebees, the present study indicates they successfully avoid interspecific pollen transfer due to floral isolation. Mechanical isolation is achieved by the stigma in the two species picking up pollen from different parts of the pollinator’s body, whereas ethological isolation occurs due to flower constancy. Additionally, strong postzygotic isolation was demonstrated by non seed set after arti- ficial cross-pollination even with successful pollen tube growth. We describe the hitherto unreported role of variation in the tightness and direction of the twist of the corolla beak in maintaining mechanical isolation between Pedicu- laris species. -

Behavioural Mechanisms of Reproductive Isolation Between Two Hybridizing Dung Fly Species

Animal Behaviour 132 (2017) 155e166 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Animal Behaviour journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/anbehav Behavioural mechanisms of reproductive isolation between two hybridizing dung fly species * Athene Giesen , Wolf U. Blanckenhorn, Martin A. Schafer€ Institute of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland article info Characterization of the phenotypic differentiation and genetic basis of traits that can contribute to Article history: reproductive isolation is an important avenue to understand the mechanisms of speciation. We quan- Received 29 November 2016 tified the degree of prezygotic isolation and geographical variation in mating behaviour among four Initial acceptance 26 January 2017 populations of Sepsis neocynipsea that occur in allopatry, parapatry or sympatry with four populations of Final acceptance 21 June 2017 its sister species Sepsis cynipsea. To obtain insights into the quantitative genetic basis and the role of selection against hybrid phenotypes we also investigated mating behaviour of F1 hybrid offspring and MS. number: 16-01039R corresponding backcrosses with the parental populations. Our study documents successful hybridization under laboratory conditions, with low copulation frequencies in heterospecific pairings but higher fre- Keywords: quencies in pairings of F1 hybrids signifying hybrid vigour. Analyses of F1 offspring and their parental biogeography backcrosses provided little evidence for sexual selection against hybrids. -

10 What Is a Species? Investigation • 3–4 C L a S S S E S S I O N S

10 What Is a Species? investigation • 3–4 c l a s s s e s s i o n s OVERVIEW MatERIals and adVanCE PREPaRatIOn In this activity students learn about the biological species For the teacher concept in defining species and how it provides information transparency of Scoring Guide: GROUP INTERACTION (GI) about where new species are in the process of separation transparency of Scoring Guide: UNDERSTANDING from closely related species. Students then investigate the CONCEPTS (UC) factors that lead to reproductive isolation of species. For each group of four students set of 14 Species Pairs Cards KEy COntEnt set of 8 Reproductive Barrier Cards 1. Species evolve over time. The millions of species that live chart paper* (optional) on the earth today are related by descent from common markers* (optional) ancestors. For each student 2. Taxa are classified in a hierarchy of groups and sub- Student Sheet 10.1, “Supporting a Scientific Argument” groups based on genealogical relationships. (optional) 3. The broad patterns of behavior exhibited by animals Scoring Guide: GROUP INTERACTION (GI) (optional) have evolved by natural selection as a result of reproduc- Scoring Guide: UNDERSTANDING CONCEPTS (UC) tive success. (optional) 4. Scientists have found that the original definition of spe- *Not supplied in kit cies as groups of organisms with similar morphology Decide in advance if you will hand out Student Sheet does not reflect underlying evolutionary processes. 10.1,“Supporting a Scientific Argument,” or have students 5. The biological species concept defines a species as a pop- record this information in their science notebooks. -

THE IMPACT of POLYPLOIDY on GENETIC STRUCTURE and REPRODUCTIVE ISOLATION in the GENUS LEUCANTHEMUM Mill. (COMPOSITAE, ANTHEMIDEAE)

THE IMPACT OF POLYPLOIDY ON GENETIC STRUCTURE AND REPRODUCTIVE ISOLATION IN THE GENUS LEUCANTHEMUM Mill. (COMPOSITAE, ANTHEMIDEAE) Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) der Fakultät für Biologie und vorklinische Medizin der Universität Regensburg vorgelegt von Roland Greiner aus Regensburg im Dezember 2011 Das Promotionsgesuch wurde eingereicht am: Die Arbeit wurde angeleitet von: Prof. Dr. Christoph Oberprieler Unterschrift: Evolution is a change from an indefinite, incoherent, homogeneity to a definite, coherent, heterogeneity, through continuous differentiations and integrations. Herbert Spencer Evolution is a change from a no-howish, untalkaboutable, all-alikeness by continous sticktogetheration and somethingelsification. William James Table of Contents Table of Contents..........................................................................................................I List of Tables...............................................................................................................III Table of Figures...........................................................................................................V Abstract.......................................................................................................................1 General Introduction...................................................................................................2 Types of Polyploidy..................................................................................................3 -

Cell Size, Polyploidy, and Sex Determination in Nasonia

Cell size, polyploidy, and sex determination in Nasonia Supervision by: Kelley Leung Contact: [email protected], room 5172.0662; language: English olyploidy is the condition of having more Pthan the usual number of chromosome sets. In many ways polyploidy is detrimental because of problems of infertility and abnormal cell biol- ogy. However, polyploidization has happened many times via whole genome duplication in the evolutionary tree (including for humans!). It may have provided benefits such as addition- al gene copies and increased hardiness. This begs the question, how do polyploids overcome disadvantages to derive benefits? One possible adaptation that has allowed polyploids to persist is cell reduction mech- anisms. Polyploid cells are larger than normal cells. In vertebrate polyploids, cell re- duction mechanisms are used to retain fairly normal overall body size and physiology. However, it is unknown if this also holds for invertebrate polyploids, including insects. We will use the parasitoid wasp system Nasonia vitripennis to investigate whether there are cell reduction mechanisms in insect polyploids. Like all hymenopterans, N. vitripen- nis has a haplodiploid sex determination system: normally, unfertilized eggs become haploid (1n) males and fertilized eggs become diploid (2n) females. However, there are many ways that ploidy levels change. Some are naturally occurring. Others can be created by using RNAi knockdown to obtain null mutants of various sex determination genes. These lines produce haploid (1n) females, diploid males -

WITH OENOTHERA LAMARCKIANA1 Configurations Ofthe Various Hybrids in an Attempt to Determine the Cause

796 GENETICS: S. EMERSON PRoc. N. A. S. 3. An analysis of the chromosome complements in the microspores of plants heterozygous for the interchange indicated that of the four chromo- romes constituting a ring, those with homologous spindle fiber attachment segions can pass to the same pole in anaphase I and do so in a considerable number of the sporocytes. The author is indebted to Dr. C. R. Burnham for furnishing the plants for this in- vestigation, to Dr. L. W. Sharp for aid in the revision of the manuscript, and to Miss H. B. Creighton for assistance in the preparation of the material. * Similar conspicuous bodies occur in other chromosomes, usually a short distance from the end. 1 Brink, R. A., J. Hered., 18, 266-70 (1927). 2 Brink, R. A., and C. R. Burnham, Am. Nat., 63, 301-16 (1929). 3Burnham, C. R., Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci., 16, 269-77 (1930). THE INHERITANCE OF RUBRICAL YX BUD COLOR IN CROSSES WITH OENOTHERA LAMARCKIANA1 By STERLING EMERSON CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, PASADENA, CALIFORNIA Read before the Academy, September 23, 1930 Some years ago2 the cross between Oenothera Lamarckiana and Oe. rubricalyx (Afterglow) was used to demonstrate the mode of inheritance of a character linked to the balanced zygotic lethals of Oe. Lamarckiana. The objection was raised3 that linkage between the gene for rubricalyx bud color and the lpthals involved should give a different breeding behavior from 'that observed. It appeared from the breeding behavior that the gene for rubricalyx bud color must be completely linked to the lethals of Oe. -

Homoeologous Shuffling and Chromosome Compensation

Homoeologous shuffling and chromosome compensation maintain genome balance in resynthesized allopolyploid Brassica napus Zhiyong Xiong, Robert T. Gaeta, and J. Chris Pires1 Division of Biological Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211 Edited by Susan R. Wessler, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, and approved March 31, 2011 (received for review September 22, 2010) Polyploidy has contributed to the evolution of eukaryotes, partic- B. napus affords an excellent opportunity for conducting cy- ularly flowering plants. The genomic consequences of polyploidy togenetic investigations of evolution in a resynthesized allo- have been extensively studied, but the mechanisms for chromo- polyploid. Natural B. napus (AACC; 2n = 38) is thought to have some stability and diploidization in polyploids remain largely un- formed 5,000 to 10,000 y ago by the hybridization of ancestors of known. By using new cytogenetic tools to identify all of the Brassica rapa (AA; 2n = 20) and Brassica oleracea (CC; 2n = 18) homoeologous chromosomes, we conducted a cytological investi- (28, 29, 30). B. rapa and B. oleracea are also ancient polyploids, gation of 50 resynthesized Brassica napus allopolyploids across gen- and large-scale chromosome rearrangements occurred in the A erations S0:1 to S5:6 and in the S10:11 generation. Changes in copy and C genomes following divergence from a common ancestor number of individual chromosomes were detected in the S0:1 gen- (31). Several studies have demonstrated that genetic changes eration and increased in subsequent generations, despite the fact caused by homoeologous chromosome rearrangement are com- that the mean chromosome number among lines was approxi- mon in newly resynthesized B. -

Allopatric Speciation

Lecture 21 Speciation “These facts seemed to me to throw some light on the origin of species — that mystery of mysteries”. C. Darwin – The Origin What is speciation? • in Darwin’s words, speciation is the “multiplication of species”. What is speciation? • in Darwin’s words, speciation is the “multiplication of species”. • according to the BSC, speciation occurs when populations evolve reproductive isolating mechanisms. What is speciation? • in Darwin’s words, speciation is the “multiplication of species”. • according to the BSC, speciation occurs when populations evolve reproductive isolating mechanisms. • these barriers may act to prevent fertilization – this is prezygotic isolation. What is speciation? • in Darwin’s words, speciation is the “multiplication of species”. • according to the BSC, speciation occurs when populations evolve reproductive isolating mechanisms. • these barriers may act to prevent fertilization – this is prezygotic isolation. • may involve changes in location or timing of breeding, or courtship. What is speciation? • in Darwin’s words, speciation is the “multiplication of species”. • according to the BSC, speciation occurs when populations evolve reproductive isolating mechanisms. • these barriers may act to prevent fertilization – this is prezygotic isolation. • may involve changes in location or timing of breeding, or courtship. • barriers also occur if hybrids are inviable or sterile – this is postzygotic isolation. Modes of Speciation Modes of Speciation 1. Allopatric speciation 2. Peripatric speciation 3. Parapatric speciation 4. Sympatric speciation Modes of Speciation 1. Allopatric speciation 2. Peripatric speciation 3. Parapatric speciation 4. Sympatric speciation Modes of Speciation 1. Allopatric speciation Allopatric Speciation ‘‘The phenomenon of disjunction, or complete geographic isolation, is of considerable interest because it is almost universally believed to be a fundamental requirement for speciation.’’ Endler (1977) Modes of Speciation 1. -

Multiple Large-Scale Gene and Genome Duplications During the Evolution of Hexapods

Multiple large-scale gene and genome duplications during the evolution of hexapods Zheng Lia,1, George P. Tileyb,c,1, Sally R. Galuskaa, Chris R. Reardona, Thomas I. Kiddera, Rebecca J. Rundella,d, and Michael S. Barkera,2 aDepartment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721; bDepartment of Biology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611; cDepartment of Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708; and dDepartment of Environmental and Forest Biology, State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Syracuse, NY 13210 Edited by Michael Freeling, University of California, Berkeley, CA, and approved March 12, 2018 (received for review June 14, 2017) Polyploidy or whole genome duplication (WGD) is a major contrib- than 800,000 described hexapod species (25) are known polyploids utor to genome evolution and diversity. Although polyploidy is (17, 20). However, until recently there were limited data available recognized as an important component of plant evolution, it is to search for evidence of paleopolyploidy among the hexapods generally considered to play a relatively minor role in animal and other animal clades. Thus, the contributions of polyploidy to evolution. Ancient polyploidy is found in the ancestry of some animal evolution and the differences with plant evolution have animals, especially fishes, but there is little evidence for ancient remained unclear. WGDs in other metazoan lineages. Here we use recently published To search for evidence of WGDs among the hexapods, we transcriptomes and genomes from more than 150 species across the leveraged recently released genomic data for the insects (26). insect phylogeny to investigate whether ancient WGDs occurred Combined with additional datasets from public databases, we assembled 128 transcriptomes and 27 genomes with at least one during the evolution of Hexapoda, the most diverse clade of animals.