Interview with Michael Wallis in New Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interview with Buz Waldmire in Springfield, Illinois

Buz Waldmire: Springfield, IL Transcribed by Nora Hickey TABLE OF CONTENTS Origins of Waldmire Road – Dad’s background – origins of Dad’s restaurants and food products (Crusty Curs, Cozy Dog, Chili-wich) – first Cozy Dog restaurant on 6th St. – presence of interstate in 1960’s – first customers/business in restaurant – South 6th St in general – area and restaurant during Buz’s young adulthood – travelers at the restaurant in ‘60’s – transition of restaurant ownership from Dad to Buz – Route 66 business – family involvement in R66 – Bob Waldmire (brother) – Bob in IL – Bob as artist – Bob and R66 – Bob and Hackberry, AZ – Bob as defining R66 persona. DAVID DUNAWAY I’m wondering how you came to live on Waldmire Road in Rochester? BUZ WALDMIRE Well, this dates back prior to the 911 system, and when there wasn’t a 911 system and there was an emergency the local ambulances or fire departments pretty much knew where everyone lived. When they went into a 911 system, and I don’t know what was involved with that, if they had to pass legislation or whatever, but they set it up they said well, where do these people live, how do we give them an address? And somebody says, I know let’s call the power company! So they called the electricity company, and they had specific records and street locations for every transformer that they hung throughout the county and in the area. It just so happened that my dad was really one of the first people out here, so when the power company came out and hung the transformer and put in the electric for the house way back in the woods, they identified it as Waldmire Road. -

Munger Moss Neon Sign

FACTORY OUTLETS ____ •••~~~ •••••'" I Stop by and visit with the Reid family. The Reids came to this Route 66 location in 1961 and operated the 66 Sunset Lodge as the Capri Motel until 1966. Then in 1972 Shepherd Hills Factory Outlet was born on the same ground as the Capri Motel. Next came the ownership of the Shepherd Hills Motel. In 1999 the Lebanon Route 66 location of the Shepherd Hills Factory Outlet moved into our new modern building. This business' has expanded and now includes eight different locations. ~OCKU 1(1 KNIVES DE BY POTTERY , SWISS ItJ 15.pobell ~Q~~~ pconds & Overstocks, 40% to 50% off Leach Service Serving the motoring public since 1949 9720 Manchester Road Rock Hill, MO 63119 (314) 962-5550 www.Leachservice.com Open 6AM-Midnight Missouri Safety & Emissions Inspections Auto Repairs, Towing, Tires-new & repairs Diesel, bp Gasoline-now with Invigorate, Kerosene Propane Tank Refills 1Qe4aue ~ iu fyt r;<J«'t ~, Ask about our Buy 5 Oil Changes Get One FREElSpecial Full Service Customers, ask about a Free Oil Change punch card. Yes, we still have Full Service where lrien.y attendants pump your gas, clean your windows and check your oil and tires Member Brentwood Chamber 01 Commerce Business Member Route 66 Association SHOW ME ROUTE 66 2 MAG A Z I N E Volume 20, Number 4 - 2010 •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE ROUTE 66 ASSOCIATION OF MISSOURI Atures ESTABLISHED JANUARY, 1990 Fe~. 27 Joplin Depot MayHave New Life 3 Officers, Board of Directors, Joe Sonderman FOLLOW THE ASSOCIATION Committees and Associations 29 Diorama Completed for the ONFACEBOOK 4 Editors Notes Lebanon Route 66 Museum Thanks to Carolyn Hasenfratz, Jeep Girl's Journal Jim Thole the Route 66 Association of Carolyn Hasenfratz 31 Warrens Route 66 Lunch Stand Missouri now has a Facebook 5 Membership Matters James H. -

OSU-Tulsa Library Michael Wallis Papers Correspondence Rev

OSU-Tulsa Library Michael Wallis papers Correspondence Rev. July 2017 AC The Art of Cars BH Beyond the Hills BTK Billy the Kid DC David Crockett EDL En Divina Luz HW Heaven’s Window LH Lincoln Highway MK Mankiller OC Oklahoma Crossroads OM Oil Man PBF Pretty Boy Floyd R66 Route 66 RWW The Real Wild West W365 The Wild West 365 WDY Way Down Yonder 1:1 21st Century Fox 66 Diner (R66) 1:2 66 Federal Credit Union Gold Club 1:3 101 Old Timers Association, The. Includes certificate of incorporation, amended by-laws, projects completed, brief history, publicity and marketing ideas. 1:4 101 Old Timers Association, The. Board and association meeting minutes, letters to members: 1995-1997. 1:5 101 Old Timers Association, The. Board and association meeting minutes, letters to members: 1998-2000. 1:6 101 Old Timers Association, The. Personal correspondence: 1995-2000. 1:7 101 Old Timers Association, The. Newsletters (incomplete run): 1995-2001. 1:8 101 Old Timers Association, The. Ephemera. 1:9 AAA AARP 1:10 ABC Entertainment 1:11 AASHTO (American Association of State Highway and Traffic Officers) 1:12 A Loves L. Productions, Inc. A-Town Merchants Wholesale Souvenirs Abell, Shawn 1:13 Abney, John (BH) Active Years 1:14 Adams, Barb Adams, Steve Adams, W. June Adams, William C. 1:15 Adler, Abigail (PBF) Adventure Tours (R66) 1:16 Adweek 1:17 Aegis Group Publishers, The A.K. Smiley Public Library Akron Police Department, The Alan Rhody Productions Alansky, Marilyn (OM) 1:18 Alaska Northwest Books 2:1 [Alberta] Albuquerque Convention and Visitors Bureau Albuquerque Journal Albuquerque Museum, The. -

2013 Route 66 International Festival August 1-3, 2013

PAGE 1 OF 7 (072613) SCHEDULE OF EVENTS FOR THE 2013 ROUTE 66 INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL AUGUST 1-3, 2013 THURSDAY, AUGUST 1 5:30 CRUISE ROUTE 66 Gathering point - the parking lot behind Joplin City Hall at 6th and Joplin Avenue Departure - 5:45 Cruise route – Joplin, Webb City, Carterville, Carthage Caution – Open course and this is at the end of rush hour Activities at the Drive-in start at 6:30 but the movie does not start until 8:55 There is plenty of time to Cruise The Route Please be safe and observe all traffic signs You can stop anywhere along the Cruise you wish – enjoy yourself If attending the SOLD OUT showing of CARS at the Route 66 Drive-In Theatre you must have a printed copy of your ticket confirmation to get into the movie AT THE DRIVE-IN, A NIGHT WITH CARS The MOVIE IS SOLD OUT Please present a printed copy of your ticket confirmation at the ticket booth to enter All tickets were sold in advance online. NO TICKETS will be sold at the Drive-in 6:30-8:30 UPON ENTERING THE DRIVE-IN: Each child under 12 will receive a ticket for drawings to win special CARS merchandise provided by Disney/Pixar Each child under 12 will receive a Meal/Dessert ticket at the Drive-in ticket booth Tickets are good for a hot dog, chips and beverage, and a dessert selection Adults and older children can purchase a hot dog, chips and beverage for $4.00 Pulled pork sandwich option available for $5.00 Clouds Meat of Carthage will be catering the meal The CARS will be shown at approximately 8:55 and is the only movie being shown Life-sized replicas of Lightning McQueen and Mater will be at the Drive-in For purchase, a photographer will be available to photograph the children with the cars Michael Wallis, the Sheriff of Radiator Springs will be swearing in young deputies Jay Ward, Pixar’s Guardian of the CARS Brand will be on hand to talk about the creation and future of the CARS films PAGE 2 OF 7 (072613) THURSDAY, AUGUST 1 CRUISE IN (THE ROUTE): At 6th & Main Street, Downtown Joplin turn left (north) to 2nd Street. -

Interview with Bob Waldmire in Portal

Interview with Bob Waldmire Portal, AZ By David King Dunaway September 7, 2007 Introductions – first meeting at Frontier in ABQ – growing up South Sixth street Springfield, Illinois --- Cozy Dog Drive-In, interviewed in revival --- history of family - -- father at Knox College --- Strand Bakery and the Goal Post --- parents meet at Strand Bakery --- writing book on his father’s life, “hot-dog-on-a-stick and world peace” --- Cozy Dog Drive-In and Dairy Queen --- growing up and working in restaurant --- brother Buz taking over --- Walgreens buying it out --- Bill Shea’s gas station --- tour buses, swatting flies, frying hamburgers --- Buz and second wife --- 66 Drive-In Theater --- Cozy baskets --- Dad pioneer in fast food “time motion man” --- wasted food, free condiment bar, “Take what you need, eat what you take” --- father in agricultural economics, vegetarianism? --- how Illinois 66 differs, corn flatness, railroad, cemeteries, Midewin Tallgrass Prairie, Queen City of the Ozarks, weather --- Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Museum, Springfield bypass --- Chicago --- Mother Jones, Mt. Olive --- East St. Louis reputation, mayor, Rock’s Bridge --- bioregionalism definition --- basin and range province – four deserts, benefits and necessity of bioregionalism --- route 66 eight states --- scorpions, tarantulas, kangaroo rats --- grasslands restoration --- family vacation 1st trip west 1962 --- Chiricahua --- Vincent Roth --- 66 Visitor’s Center in Hackberry --- Chiricahua Nature Sanctuary --- annoying tourists, didn’t want to do it -

Oklahoma-Route-66-Guide

OKLAHOMA THE ULTIMATE ROAD TRIP You’ve got that old familiar itch — the need for adventure. Possibility hangs in the air as you hit the road. You fill up the gas tank, pocket your GPS, and head for that ribbon of highway. The Road – not just any road – but the ever-changing, always- engaging, wide-open Route 66, lays in front of you on this ultimate road trip. You’ll discover a heady mix of history, romance and pop culture. You’ll meet the people, places and icons of the legendary Mother Road. You’ll feel the heat of adventure as you anticipate what’s around the next bend in the road or over the crest of the next horizon. And soon, very soon, as you travel this most complex of roads, you come to understand what people mean when they talk about the freedom of the road and getting your kicks on Oklahoma’s stretch of Route 66. Your guide to the Ultimate Road Trip this guide is Your starting place. information and websites to browse for more info. Get your motor runnin’, Charm the wheels off your favorite Route 66 There are so many things to see and do on For more detailed travel information and Head out on the highway buff with a collectible Route 66 that it’s impossible to list them all in instructions on finding original Route 66 roadbed in from the Route 66 collection of TravelOK.com’s Okie Lookin’ for adventure, this guide. You’ll find a bit of the new and old Oklahoma and meticulous insights into the Mother Boutique. -

Route 66 Economic Impact Study Contents 6 SECTION ONE Introduction, History, and Summary of Benefi Ts

SYNTHESIS OF FINDINGS A study conducted by Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in collaboration with the National Park Service Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program and World Monuments Fund Study funded by American Express SYNTHESIS OF FINDINGS A study conducted by Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in collaboration with the National Park Service Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program and World Monuments Fund Study funded by American Express Center for Urban Policy Research Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey New Brunswick, New Jersey June 2011 AUTHORS David Listokin and David Stanek Kaitlynn Davis Michael Lahr Orin Puniello Garrett Hincken Ningyuan Wei Marc Weiner with Michelle Riley Andrea Ryan Sarah Collins Samantha Swerdloff Jedediah Drolet Charles Heydt other participating researchers include Carissa Johnson Bing Wang Joshua Jensen Center for Urban Policy Research Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey New Brunswick, New Jersey ISBN-10 0-9841732-3-4 ISBN-13 978-0-9841732-3-5 This report in its entirety may be freely circulated; however content may not be reproduced independently without the permission of Rutgers, the National Park Service, and World Monuments Fund. 1929 gas station in Mclean, Texas Route 66 Economic Impact Study contents 6 SECTION ONE Introduction, History, and Summary of Benefi ts 16 SECTION TWO Tourism and Travelers 27 SECTION THREE Museums and Route 66 30 SECTION FOUR Main Street and Route 66 39 SECTION FIVE The People and Communities of Route 66 51 SECTION SIX Opportunities for the Road 59 Acknowledgements 5 SECTION ONE Introduction, History, and Summary of Benefi ts unning about 2,400 miles from Chicago, Illinois, to Santa Monica, California, Route 66 is an American and international icon, myth, carnival, and pilgrimage. -

Illinois Group Tour Planner

ILL_1.qxp_Layout 1 3/21/19 10:53 AM Page 1 Group-Friendly ILLINOISGroup Tour Planner Tour Ideas GO OUTSIDE, GET ACTIVE The Land of Lincoln is an outdoor haven ARCHITECTURAL WONDERS Illinois contains a myriad of eye-pleasing masterpieces EAT, DRINK AND BE MERRY Delicious restaurants can be found throughout the state ILL_2.qxp_Layout 1 3/21/19 2:15 AM Page 2 ILL_3.qxp_Layout 1 3/21/19 2:32 AM Page 3 ILL_4.qxp_Itineraries 3/21/19 11:34 AM Page 4 ILLINOISGroup Tour Planner CONTENTS 18 40 Ranvestal Photographic/Choose Chicago Photographic/Choose Ranvestal 8 28 44 Bob Bob Weder Randy Mink Randy FEATURES SAMPLE ITINERARIES 8 Route 66: A Trip Down Memory Lane 14 Land of Lincoln Illinois attractions recall the glory days of an iconic road steeped in lore and tradition 24 Chicago Neighborhoods 18 Architectural Wonders 32 Statewide Illinois brims with eye-pleasing masterpieces 36 Chicago and Beyond Go Outside, Get Active All itineraries are samples and can be 28 customized to fit your group’s needs With hundreds of acres of parks and forests and miles of trails, Illinois is an outdoor haven 40 Eat, Drink and Be Merry Groups looking to please their palates have plenty of delectable options in the Land of Lincoln 44 Bridging Generations ON THE COVER More and more family vacations include grandma and grandpa Illinois Route 66 Hall of Fame and Museum in Pontiac (Photo courtesy of Illinois Office of Tourism) 4 ILLINOIS GROUP TOUR PLANNER ILL_5.qxp_Layout 1 3/21/19 2:36 AM Page 5 CHICAGO’S NORTH SHORE Bahá’í House of Illinois Holocaust Worship Museum Chicago Botanic Garden Halim Time and Glass Museum Bordering Chicago along Lake Michigan, Chicago’s North Shore is the most scenic area in metropolitan Chicago. -

Pawnee Bill's Life As Viewed by Bloomington Residents Eric Willey Illinois State University, [email protected]

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Faculty and Staff ubP lications – Milner Library Milner Library 2016 One of Our Own: Pawnee Bill's Life as Viewed by Bloomington Residents Eric Willey Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/fpml Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Library and Information Science Commons, Public History Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Willey, Eric. "One of Our Own: Pawnee Bill's Life as Viewed by Bloomington Residents." Bandwagon, 60, no. 4 (2016): 72-90. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Milner Library at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty and Staff ubP lications – Milner Library by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. One of Our Own: Pawnee Bill's Life as Viewed by Bloomington Residents Gordon William Lillie was born 14 February 1860 or 1861 in Bloomington, Illinois.1 The son of a laborer, Lillie achieved fame as one of the great Western heroes, and became known world- wide as Pawnee Bill. While Lillie left Bloomington early in his life and only later achieved his considerable fame, and eventually retired to a privately owned ranch near Pawnee, Oklahoma, his home town remained aware of his pedigree and followed his exploits through newspaper reports and other media. Although his early activities with fellow Western icon Buffalo Bull were largely ignored by the local press (and often fabricated by dime novel writers who considerably confused the historical record), later visits from Lillie's wild west exhibition were often described in local papers, and when (primarily in his later life) he reinforced community ties by returning to Bloomington to visit, the local press showed an enthusiasm for him as a Bloomington native who had achieved international fame but not forgotten his local roots. -

Cars Is a 2006 American Computer-Animated Comedy-Adventure Sports Film Produced by Pixar Animation Studios and Released by Walt Disney Pictures

Cars is a 2006 American computer-animated comedy-adventure sports film produced by Pixar Animation Studios and released by Walt Disney Pictures. Directed and co -written by John Lasseter, it is Pixar's final independently-produced motion pic ture before its purchase by Disney. Set in a world populated entirely by anthrop omorphic cars and other vehicles, it features the voices of Owen Wilson, Paul Ne wman (in his final non-documentary feature), Larry the Cable Guy, Bonnie Hunt, T ony Shalhoub, Cheech Marin, Michael Wallis, George Carlin, Paul Dooley, Jenifer Lewis, Guido Quaroni, Michael Keaton, Katherine Helmond, and John Ratzenberger. It is also the second Pixar filmafter A Bug's Lifeto have an entirely non-human ca st. The film was accompanied by the short One Man Band for its theatrical and ho me media releases. Cars premiered on May 26, 2006 at Lowe's Motor Speedway in Concord, North Caroli na and was theatrically released on June 9, 2006, to positive reviews. It was no minated for two Academy Awards, including Best Animated Feature, and won the Gol den Globe Award for Best Animated Feature Film. The film was released on DVD on November 7, 2006 and to Blu-ray Disc in late 2007. Related merchandise, includin g scale models of several of the cars, broke records for retail sales of merchan dise based on a Disney·Pixar film,[2] bringing an estimated $10 billion in 5 years since the film's release.[3] The film was dedicated to Joe Ranft, who was kille d in a car accident during the film's production. -

1 “I Grew up Loving Cars and the Southern California Car Culture. My Dad Was a Parts Manager at a Chevrolet Dealership, So V

“I grew up loving cars and the Southern California car culture. My dad was a parts manager at a Chevrolet dealership, so ‘Cars’ was very personal to me — the characters, the small town, their love and support for each other and their way of life. I couldn’t stop thinking about them. I wanted to take another road trip to new places around the world, and I thought a way into that world could be another passion of mine, the spy movie genre. I just couldn’t shake that idea of marrying the two distinctly different worlds of Radiator Springs and international intrigue. And here we are.” — John Lasseter, Director ABOUT THE PRODUCTION Pixar Animation Studios and Walt Disney Studios are off to the races in “Cars 2” as star racecar Lightning McQueen (voice of Owen Wilson) and his best friend, the incomparable tow truck Mater (voice of Larry the Cable Guy), jump-start a new adventure to exotic new lands stretching across the globe. The duo are joined by a hometown pit crew from Radiator Springs when they head overseas to support Lightning as he competes in the first-ever World Grand Prix, a race created to determine the world’s fastest car. But the road to the finish line is filled with plenty of potholes, detours and bombshells when Mater is mistakenly ensnared in an intriguing escapade of his own: international espionage. Mater finds himself torn between assisting Lightning McQueen in the high-profile race and “towing” the line in a top-secret mission orchestrated by master British spy Finn McMissile (voice of Michael Caine) and the stunning rookie field spy Holley Shiftwell (voice of Emily Mortimer). -

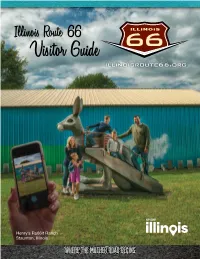

Visitor Guide

Welcome to Illinois Route 66 The Experience of a Lifetime! The Mother Road in Illinois is the place to search out the perfect piece of homemade pie, neon signs you won’t see anywhere else, an honest-to-goodness rabbit ranch, and a whole slew of larger and small towns that truly are the “real America.” For all event listings and other up-to-date information visit: illinoisroute66.org Map and History Restaurants pics on 66 pages 2 and 3 page 4 page 5 breweries museums Abraham Lincoln on 66 page 7 page 8 page 9 events downtown districts giants page 10 page 12 page 13 interpretive exhibits page 16 community listings pages 17-58 outdoors pages 32-33 neon vintage 66 Lodging pages 60-62 page 15 page 14 more info page 64 Printed in the U.S.A. April 2020 50M Index of Communities The communities in this visitors guide are listed as they are found along Route 66 traveling from north to south. If you are looking for information on a particular community, please use the table of contents below with corresponding page numbers. Atlanta ...................................37 Auburn ..................................51 Benld .....................................53 Berwyn ..................................18 Bloomington ..........................31 Bolingbrook ...........................20 Braceville ...............................25 Braidwood .............................25 Broadwell ..............................42 Carlinville ...............................52 Cayuga ..................................26 Channahon ............................20 Chatham