Case Studies of the People and Places of Route 66

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8364 Licensed Charities As of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T

8364 Licensed Charities as of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T. Rowe Price Program for Charitable Giving, Inc. The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust USA, Inc. 100 E. Pratt St 25283 Cabot Road, Ste. 101 Baltimore MD 21202 Laguna Hills CA 92653 Phone: (410)345-3457 Phone: (949)305-3785 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 MICS 52752 MICS 60851 1 For 2 Education Foundation 1 Michigan for the Global Majority 4337 E. Grand River, Ste. 198 1920 Scotten St. Howell MI 48843 Detroit MI 48209 Phone: (425)299-4484 Phone: (313)338-9397 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 46501 MICS 60769 1 Voice Can Help 10 Thousand Windows, Inc. 3290 Palm Aire Drive 348 N Canyons Pkwy Rochester Hills MI 48309 Livermore CA 94551 Phone: (248)703-3088 Phone: (571)263-2035 Expiration Date: 07/31/2021 Expiration Date: 03/31/2020 MICS 56240 MICS 10978 10/40 Connections, Inc. 100 Black Men of Greater Detroit, Inc 2120 Northgate Park Lane Suite 400 Attn: Donald Ferguson Chattanooga TN 37415 1432 Oakmont Ct. Phone: (423)468-4871 Lake Orion MI 48362 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Phone: (313)874-4811 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 25388 MICS 43928 100 Club of Saginaw County 100 Women Strong, Inc. 5195 Hampton Place 2807 S. State Street Saginaw MI 48604 Saint Joseph MI 49085 Phone: (989)790-3900 Phone: (888)982-1400 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 58897 MICS 60079 1888 Message Study Committee, Inc. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Interview with Buz Waldmire in Springfield, Illinois

Buz Waldmire: Springfield, IL Transcribed by Nora Hickey TABLE OF CONTENTS Origins of Waldmire Road – Dad’s background – origins of Dad’s restaurants and food products (Crusty Curs, Cozy Dog, Chili-wich) – first Cozy Dog restaurant on 6th St. – presence of interstate in 1960’s – first customers/business in restaurant – South 6th St in general – area and restaurant during Buz’s young adulthood – travelers at the restaurant in ‘60’s – transition of restaurant ownership from Dad to Buz – Route 66 business – family involvement in R66 – Bob Waldmire (brother) – Bob in IL – Bob as artist – Bob and R66 – Bob and Hackberry, AZ – Bob as defining R66 persona. DAVID DUNAWAY I’m wondering how you came to live on Waldmire Road in Rochester? BUZ WALDMIRE Well, this dates back prior to the 911 system, and when there wasn’t a 911 system and there was an emergency the local ambulances or fire departments pretty much knew where everyone lived. When they went into a 911 system, and I don’t know what was involved with that, if they had to pass legislation or whatever, but they set it up they said well, where do these people live, how do we give them an address? And somebody says, I know let’s call the power company! So they called the electricity company, and they had specific records and street locations for every transformer that they hung throughout the county and in the area. It just so happened that my dad was really one of the first people out here, so when the power company came out and hung the transformer and put in the electric for the house way back in the woods, they identified it as Waldmire Road. -

Regional Municipal Planning Strategy

Regional Municipal Planning Strategy OCTOBER 2014 Regional Municipal Planning Strategy I HEREBY CERTIFY that this is a true copy of the Regional Municipal Planning Strategy which was duly passed by a majority vote of the whole Regional Council of Halifax Regional Municipality held on the 25th day of June, 2014, and approved by the Minister of Municipal Affairs on October 18, 2014, which includes all amendments thereto which have been adopted by the Halifax Regional Municipality and are in effect as of the 05th day of June, 2021. GIVEN UNDER THE HAND of the Municipal Clerk and under the corporate seal of the Municipality this _____ day of ____________________, 20___. ____________________________ Municipal Clerk TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 THE FIRST FIVE YEAR PLAN REVIEW ......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 VISION AND PRINCIPLES ................................................................................................................................ 3 1.3 OBJECTIVES ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.4 HRM: FROM PAST TO PRESENT .................................................................................................................... 7 1.4.1 Settlement in HRM ................................................................................................................................... -

Numerical Simulation of the Howard Street Tunnel Fire

Fire Technology, 42, 273–281, 2006 C 2006 Springer Science + Business Media, LLC. Manufactured in The United States DOI: 10.1007/s10694-006-7506-9 Numerical Simulation of the Howard Street Tunnel Fire Kevin McGrattan and Anthony Hamins, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD 20899, USA Published online: 24 April 2006 Abstract. The paper presents numerical simulations of a fire in the Howard Street Tunnel, Baltimore, Maryland, following the derailment of a freight train in July, 2001. The model was validated for this application using temperature data collected during a series of fire experi- ments conducted in a decommissioned highway tunnel in West Virginia. The peak predicted temperatures within the Howard Street Tunnel were approximately 1,000◦C (1,800◦F) within the flaming regions, and approximately 500◦C (900◦F) averaged over a length of the tunnel equal to about four rail cars. Key words: fire modeling, Howard Street Tunnel fire, tunnel fires Introduction On July 18, 2001, at 3:08 pm, a 60 car CSX freight train powered by 3 locomotives traveling through the Howard Street Tunnel in Baltimore, Maryland, derailed 11 cars. A fire started shortly after the derailment. The tunnel is 2,650 m (8,700 ft, 1.65 mi) long with a 0.8% upgrade in the section of the tunnel where the fire occurred. There is a single track within the tunnel. Its lower entrance (Camden portal) is near Orioles Park at Camden Yards; its upper entrance is at Mount Royal Station. The train was traveling towards the Mount Royal portal when it derailed. -

Avis Budget Group Optimizes Vehicle Rental Services Using Real-Time Data

Connecting a Global Fleet: Avis Budget Group Optimizes Vehicle Rental Services Using Real-Time Data “ Informatica lets us use real-time data to optimize fleet management and telematics so that we can save money and drive our bottom line.” Christopher Cerruto VP of Global Enterprise Architecture and Analytics Avis Budget Group Goals Solution Results Connect a massive fleet of 650,000 vehicles in real Deploy Informatica solutions on AWS to operationalize Supports global vehicle analytics with an end-to-end time and with a complete global view to enhance data and perform real-time analytics as part of a next- data pipeline, giving fleet managers faster access to efficiency, reduce costs, and drive revenue generation platform track vehicles in real time Reduce business risk by profiling and governing Leverage Informatica Data Engineering Integration Mitigates risk by improving data quality and telematics data from vehicle GPS and navigation to enable faster, flexible, and repeatable big data governance, helping to ensure that fleet data is systems and uncovering data quality issues early ingestion and integration complete and in the right format Document core assets such as fleet and telematics Organize fleet and telematics data using Informatica Increases productivity by enabling business users to data while capturing business context from subject Enterprise Data Catalog to provide visibility into data search for, locate, and understand data assets on their matter experts location, lineage, and business context own, with a line of sight into data lineage Business Requirements: Informatica Success Story: Avis Budget Group Avis Budget Group is a leading general-use vehicle rental company, operating some of the most recognized • Execute full-scale production pilots in short brands in the industry, including: Avis, Budget, and Zipcar. -

Interview with Michael Wallis in New Mexico

INTERVIEW WITH MICHAEL WALLIS by David K. Dunaway 1/6/06 Early days in New Mexico – Taos – his new book, En Divinia Luz – life in Santa Fe: meeting Thornton Wilder – least-known corners of Route 66 – “avoid the cities” – 66 and the Lincoln Highway – different alignments – Dennis Casebier and Ted Drewes – 66 as “Cliff Notes” – unusual stories: Paul Heeler, dancing along 66 – Wanda Queenan – Grapes of Wrath actors – sidewalk highway – “in” versus “near” route 66 – Shoe Tree Trading Post – characters (Oklahoma) – Harley and Annabelle Russell – Frankoma Pottery – inter-generational families on 66 – Tulsa Historical Society – Beryl Ford photo collection – museums (Illinois), collectors (Missouri) – Emily Priddy at the Tulsa Globe – collectors and collections along the Route: Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, California U:\Oral History\DunawayInterviews\INTERVIEW Michael Wallis.doc 1 DAVID DUNAWAY: I worked right across the way, living just behind the Tres Piedras, the Three Rocks Café, and working at Taos Photographic in Governor Bent’s house – our paths may have crossed at that time. MICHAEL WALLIS: My first summer in New Mexico, I didn’t have a car up there in Taos. I walked. Every other day I walked from the Wurlitzer Foundation to the post office, which was of course a big gathering place for everyone to get their mail. I carried a huge sycamore stick to literally beat dogs off of me. They finally learned. They were savage. I love animals, but these dogs were after my ass, and I just had to whack them a few times. Here I am again, an idealistic writer. -

DMV Driver Manual

New Hampshire Driver Manual i 6WDWHRI1HZ+DPSVKLUH DEPARTMENT OF SAFETY DIVISION OF MOTOR VEHICLES MESSAGE FROM THE DIVISION OF MOTOR VEHICLES Driving a motor vehicle on New Hampshire roadways is a privilege and as motorists, we all share the responsibility for safe roadways. Safe drivers and safe vehicles make for safe roadways and we are pleased to provide you with this driver manual to assist you in learning New Hampshire’s motor vehicle laws, rules of the road, and safe driving guidelines, so that you can begin your journey of becoming a safe driver. The information in this manual will not only help you navigate through the process of obtaining a New Hampshire driver license, but it will highlight safe driving tips and techniques that can help prevent accidents and may even save a life. One of your many responsibilities as a driver will include being familiar with the New Hampshire motor vehicle laws. This manual includes a review of the laws, rules and regulations that directly or indirectly affect you as the operator of a motor vehicle. Driving is a task that requires your full attention. As a New Hampshire driver, you should be prepared for changes in the weather and road conditions, which can be a challenge even for an experienced driver. This manual reviews driving emergencies and actions that the driver may take in order to avoid a major collision. No one knows when an emergency situation will arise and your ability to react to a situation depends on your alertness. Many factors, such as impaired vision, fatigue, alcohol or drugs will impact your ability to drive safely. -

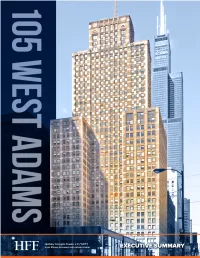

Chicago’S Central Loop

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Holliday Fenoglio Fowler, L.P. (“HFF”) is pleased to present the outstanding KEY PROPERTY STATISTICS value-add investment opportunity to obtain a fee simple interest in 105 West Property Type Office with Ground Adams Street (also known as The Clark Adams Building for its prominence at Floor Retail the corner of this historic intersection), a historic 41-story 314,855 RSF office Total Area Total: 314,855 RSF tower located in the heart of Chicago’s Central Loop. Originally known as the Office: 306,705 RSF Retail: 8,150 RSF Banker’s Building, the Burnham Brothers, sons of the renowned architect and 63.0% urban designer, Daniel Burnham, completed the Property in 1927 which at the Percent Leased time was the tallest continuous-clad brick building in Chicago. The Property Stories 41 Stories is a multi-tenant office building sitting on top of a separately owned 430-room Club Quarters Hotel (floors 3-10) which opened in 2001 as well as Elephant Date Completed/ 1927/1988/1999/ & Castle, a pub and restaurant (also not included in the offering). The neo- Renovated 2006 - 2011 classical structure is the tallest continuous-clad brick building in Chicago and Average Floor Plates 17,000 RSF is primly located adjacent to the Federal Government Core, a multi-building area including Mies van der Rohe’s Federal Plaza and City Hall, as well as the Slab to Slab Ceiling 12' LaSalle Street Corridor, the address of choice for many of Chicago’s prominent Height law firms, financial institutions, and professional service firms. The Clark Adams Building meets all the prerequisites for an exceptional oppor- tunistic investment; current vacancy, attractive basis, substantial development potential, an extremely favorable financing environment and a realistic and readily achievable exit strategy. -

“1 EDERAL \ 1 9 3 4 ^ VOLUME 20 NUMBER 47 * Wa N T E D ^ Washington, Wednesday, March 9, 1955

\ utteba\ I SCRIPTA I { fc “1 EDERAL \ 1 9 3 4 ^ VOLUME 20 NUMBER 47 * Wa n t e d ^ Washington, Wednesday, March 9, 1955 TITLE 5— ADMINISTRATIVE material disclosure: § 3.1845 Composi CONTENTS tion: Wool Products Labeling Act; PERSONNEL § 3.1900 Source or origin: Wool Products Agricultural Marketing Service PaS0 Labeling Act. Subpart—Offering unfair, Proposed rule making: Chapter I— Civil Service Commission improper and deceptive inducements to Milk handling in Wichita, Kans_ 1405 Part 6—Exceptions P rom the purchase or deal: § 3.1982 Guarantee— Agricultural Research Service Competitive S ervice statutory: Wool Products Labeling Act. Proposed rule making: DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE Subpart—V sing misleading nam e— Foreign quarantine notices; for Goods: § 3.2280 Composition. I. In con eign cotton and covers______ 1407 Effective upon publication in the F ed nection with the introduction or manu eral R egister, paragraph (j) is added facture for introduction into commerce, Agriculture Department to § 6.104 as set out below. or the offering for sale, sale, transporta See Agricultural Marketing Serv ice; Agricultural Research Serv § 6.104 Department of Defense. * * * tion or distribution in commerce, of sweaters or other “wool products” as such ice; Rural Electrification Ad (j) Office of Legislative Programs. ministration. (1) Until December 31,1955, one Direc products are defined in and subject to the tor of Legislative Programs, GS-301-17. Wool Products Labeling Act of 1939, Bonneville Power Administra (2) Until December 31, 1955, two Su which products contain, purport to con tion pervisory Legislative Analysts, GS- tain or in any way are represented as Notices: 301-15. -

Department of English And

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND COMPARATIVE LITERATURE Spring 2015 Newsletter Cindy Baer: An Outstanding Nurturer of Table of Contents Success By Aaron Thein and Giselle Tran Cindy Baer: An Outstanding Nurturer of Success 1 he average preschooler will begin to use their motor skills and learn to have fun by running Robert Cullen: Leaving a Lasting around, jumping on one foot, or skipping. Dr. Impression in SJSU History 2 T Cindy Baer, how- ever, was not an av- Spotlight on Visiting Professor Andrew Lam 4 erage preschooler. “I’ve known since Celebrating a Career: Dr. Bonnie Cox is Retiring 5 I was five years old that I wanted to be Dr. Katherine Harris Publishes New Book on a teacher,” she says, the British Literary Annual 6 having developed a hobby of writing Student Success Funds Awarded to Professional quizzes for her and Technical Writing Program 7 imaginary students at that age. She re- alized her dream of Spartans’ Steinbeck 8 becoming a teacher when she received The English Department Goes to Ireland 10 her MA in 1983 and her PhD in 1994 from the University of Washington National Adjunct Walkout Day 11 in Seattle. And now, in March 2015, she has been given the Outstanding Lecturer Award of 2015—an award Now Hiring: Writing Specialists 12 that considers eligible lecturers from all departments of SJSU—as well as hired in the tenure-track position of Welcoming Doctor Ryan Skinnell 14 Assistant Writing Programs Administrator. Upon receiving all the good news, Dr. Baer admits Reading Harry Potterin Academia 15 it felt surreal. -

Downtown Phoenix Map and Directory

DOWNTOWN • MAP & DIRECTORY 2017 2018 A publication of the Downtown Phoenix Partnership and Downtown Phoenix Inc. Welcome to Downtown Phoenix! From award-winning restaurants to exciting sports events and concerts, Downtown Phoenix is the epicenter of fun things to do in the area. Come see for yourself— the door is open. ABOUT THE COVER Historically, visual cues like glass skyscrapers, large concrete garages and people wearing suits clearly identified Downtown Phoenix as a business and commerce center. But during the last decade, it has developed into so much more than that. Over time, downtown started looking younger, staying up later, and growing into a much more diverse and Eat Stay interesting place. The vibrant street art and mural American • 3 Hotels • 17 scene represents some of those dynamic changes. Asian • 4 Housing • 17 Splashes of color, funky geometric patterns and thought-provoking portraits grace many of the Coffee & Sweets • 7 buildings and businesses around downtown. From Deli & Bistro • 8 street art to fine art, murals are becoming a major Services Irish & British • 8 source of Downtown Phoenix pride. Auto • 18 Italian • 8 Banking • 18 ABOUT THE ARTIST Mediterranean • 9 Beauty & Grooming • 18 JB SNYDER Mexican & Southwestern • 9 Courts & Government • 19 The 1960s and ‘70s revolutionized popular music, Vendors • 9 Education • 19 and some of the album covers from that time were Electronics • 21 just as cutting-edge. Drawing inspiration from the colorful and psychedelic images associated with Play Health & Fitness • 21 the classic rock era, artist and muralist JB Snyder Arts & Culture • 10 Insurance • 22 uses continuous lines, bright colors and hidden Bars & Nightlife • 10 Print & Ship • 22 images to add a sense of musicality and intrigue to his designs.